Life as Divine Alchemy

John Donne's "A Nocturnal upon St. Lucy's Day"

Religion seems to superimpose. Knowledge mediated through its symbols. Meaning lacquered onto the mundane. Salvation bound up with suffering. In a religious life, one is invited to view existence differently—to view it divinely.

C.S. Lewis invites us to consider the difference between looking at and looking along. In his toolshed, Lewis tracks a squib of light as it filters through a crack between door and jamb while contemplating the beauty of dancing particles caught in an amber beam. As he stands in the light and looks through it, the toolshed vanishes. Instead he sees, “framed . . . [through] the top of the door, green leaves moving on the branches of a tree outside and beyond that, 90 odd million miles away, the sun.” This new view of proximal leaves and distant sun still falls short of what is going on in the sunbeam: the clinical description of what-is-seen fails to capture what-is-there.

The pressing question here is why is it so difficult to describe this looking-along? Especially when confronted with what cannot be expressed, we feel we must remain silent. The idyllic scene of a dusty beam of light contrasted with the vast expanses of space do no justice to what might actually be. Even still we feel compelled and at times inspired to make the attempt in the face of the inexpressible. I may spend all my time looking at the light, appreciating its singular beauty, its unique play in a darkened space. In doing so, however, I risk missing the vistas in the light’s very existence. Looking along this light—participating in and being filled by it—opens the possibilities of perspective and invites a new look at what at first appears mundane.

Poetry seems to superimpose. Experience described through word. Meaning layered through metaphor. It parallels life through perspective.

I wish to invite the inexpressible if such a thing is even possible.

To illustrate this, I turn now to a lesser-known poem by John Donne, “A Nocturnal upon St. Lucy’s Day.” Donne is a particular favorite of mine. His poetry is deeply steeped in life, his work saturated in care and toil. His words are intriguing to look at, his meter is difficult, and his form often defies description. This seems to me an important parallel to religious experience—to life. If you are ready, permit me to accept the invitation on your behalf. Let us attempt together to look along that which may best be left unsaid.

'Tis the year's midnight, and it is the day's,

Lucy's, who scarce seven hours herself unmasks;

The sun is spent, and now his flasks

Send forth light squibs, no constant rays;

The world's whole sap is sunk;

The general balm th' hydroptic earth hath drunk,

Whither, as to the bed's feet, life is shrunk,

Dead and interr'd; yet all these seem to laugh,

Compar'd with me, who am their epitaph.

Study me then, you who shall lovers be

At the next world, that is, at the next spring;

For I am every dead thing,

In whom Love wrought new alchemy.

For his art did express

A quintessence even from nothingness,

From dull privations, and lean emptiness;

He ruin'd me, and I am re-begot

Of absence, darkness, death: things which are not.

All others, from all things, draw all that's good,

Life, soul, form, spirit, whence they being have;

I, by Love's limbec, am the grave

Of all that's nothing. Oft a flood

Have we two wept, and so

Drown'd the whole world, us two; oft did we grow

To be two chaoses, when we did show

Care to aught else; and often absences

Withdrew our souls, and made us carcasses.

But I am by her death (which word wrongs her)

Of the first nothing the elixir grown;

Were I a man, that I were one

I needs must know; I should prefer,

If I were any beast,

Some ends, some means; yea plants, yea stones detest,

And love; all, all some properties invest;

If I an ordinary nothing were,

As shadow, a light and body must be here.

But I am none; nor will my sun renew.

You lovers, for whose sake the lesser sun

At this time to the Goat is run

To fetch new lust, and give it you,

Enjoy your summer all;

Since she enjoys her long night's festival,

Let me prepare towards her, and let me call

This hour her vigil, and her eve, since this

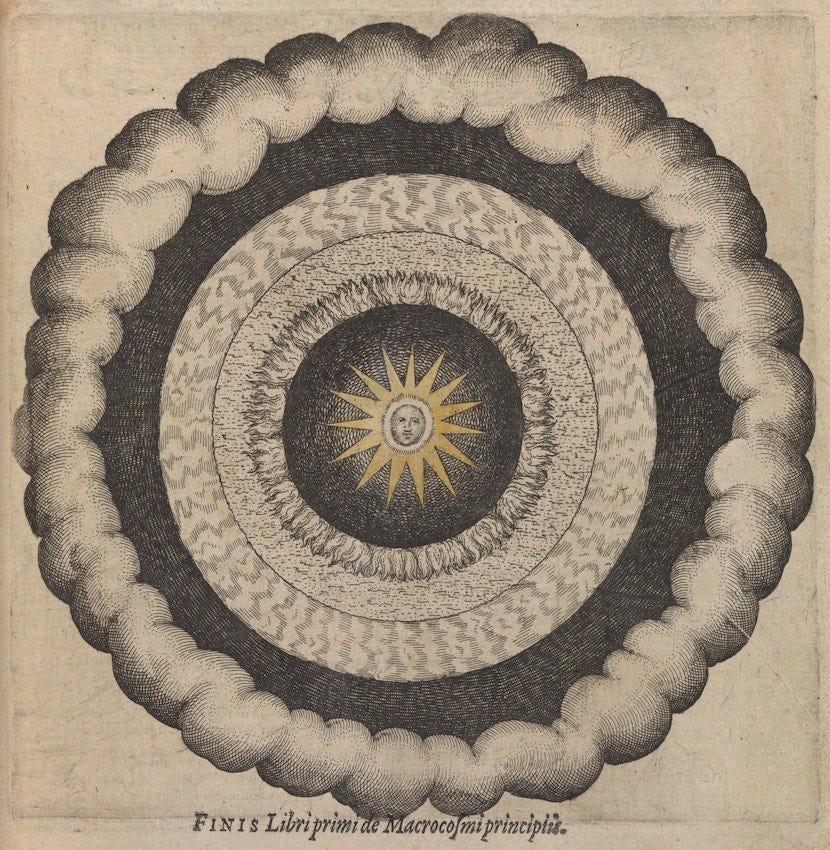

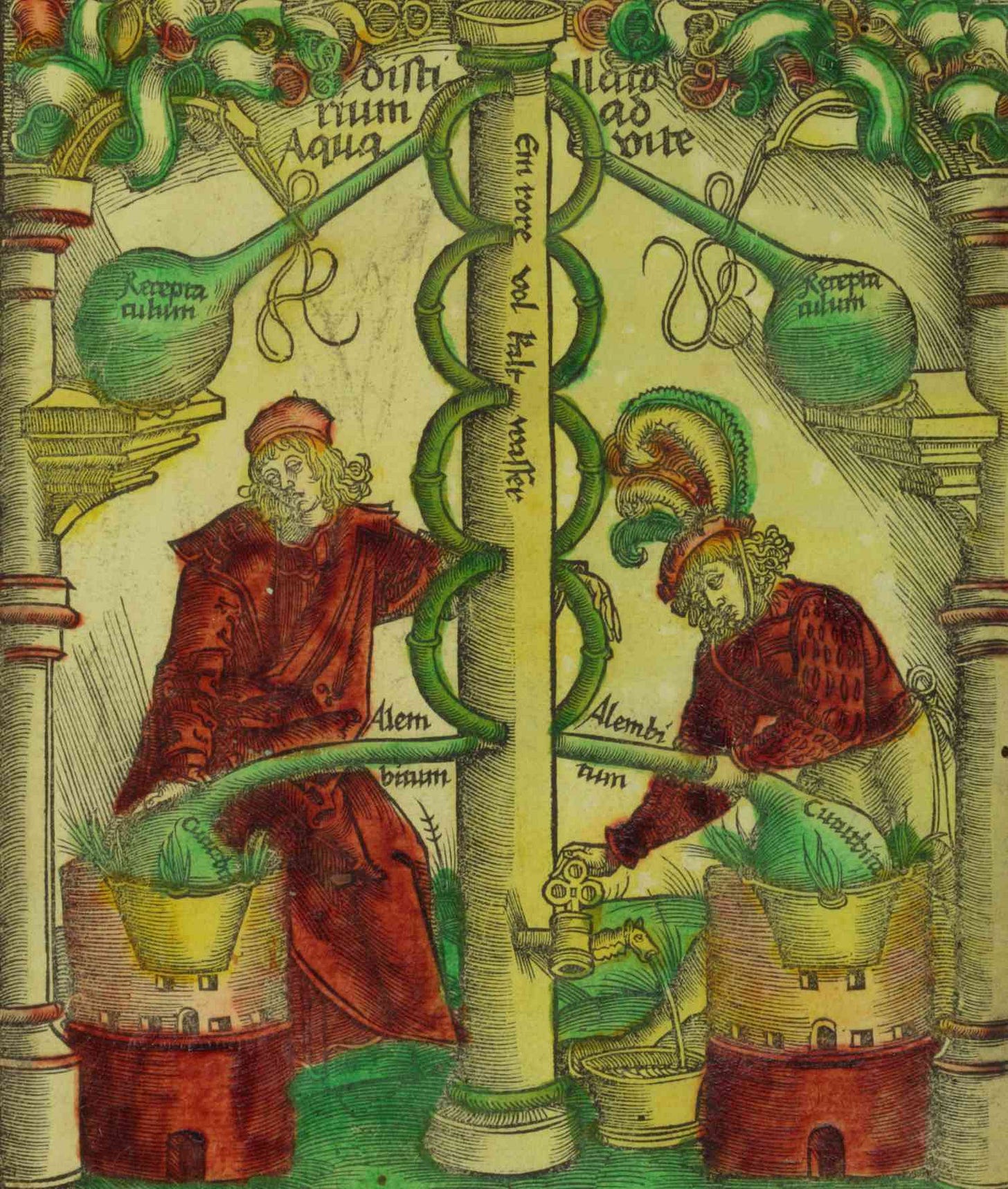

Both the year's, and the day's deep midnight is.We begin in the middle, much as Lucy’s Day, which falls on December 13, is a middle of sorts. What is this “new alchemy”? Alchemy seeks to make base things precious. In “Nocturnal,” light distills from darkness. Though dour the language and bleak the tone, a distilled particle of Love trickles through the dismal, snowy backdrop of wintry death to light his vigil on St. Lucy’s Day.

And dismal is that canvas! Twice midnight, as both the year and the day draw to a close, suggests the deepest of dark stillness—perhaps closer to death than life-loving souls dare tread. This double darkness—the shortest day and midnight on a year-clock standing opposite the noontide of Summer Solstice—is indeed oppressive at a year’s end. The sun spent, the sap sunk, life itself shrinks away from the lowring, inevitable night of nights.

Light! Lucy’s very name is Light, and though the sun sputters shortly on her day, light is present in the inconstant rays, in the sap’s sinking, and the earth’s drinking. This life-giving light is what will bring the “next world” and wreak a “new alchemy.”

Donne makes no overt allusions to Christ in “Nocturnal,” but the “general balm [which] th’hydroptic earth hath drunk” connects light squibs to the creation of life-sap which sinks in the trees. If we look along these weak rays further, St. Lucy’s Day marks the midpoint of Advent with its beacon of Christmas light in the long dark of winter. This celebration of Christ as Lord and Creator is the Light which can follow one into wintry death and create anew, for he is also Love. This new alchemy makes us re-begotten in spite of the voids of “things which are not.”

The elder poet observes life and love from the other end of where lovers start. His view springs from nothingness, dull privations, emptiness, absence, darkness, and death. In Christ there is wrought a resurrection. Indeed, Life from death is the ultimate something-from-nothing, light in deepest darkness wrought through Love, forging a “quintessence even from nothingness.” A light-to-love-to-life. A new alchemy.

What is alchemy, but something both measured and mystical? There is a certain science to its superstition, a method to the arcane expressed in the idea. Medieval mages attempting to rework lead into gold point to the birth of something valuable or noble from something existent, yet base. But man is not metal, be he base or noble. Love, it seems, can change one from a well of emptiness to a “grave of all that’s nothing,” a place where nothing and emptiness go to die. When a person experiences Love in its fullest sense— and here I mean not mere passion, passing fancy, or even romance, though they can each be included in it—it must be in its distilled form. It must be encountered as “Love’s limbec.” Upon drinking this concentrated draught our whole being changes and we go from being one with “every dead thing” to things-which-are. We are ruined as to the dark and the empty.

Things-which-are are not always pleasant in themselves! As a thing-which-is the “ordinary nothing[s]” still pass in and through us. Weeping often accompanies Love, for example: “Oft a flood have we two wept, and so drown’d the whole world, us two.” This weeping and flooding of the world call back the light squibs and sap from the first stanza which sink into the earth in preparation for Spring. Abandon all vapid optimism here! We are remade through “sad experience” (D&C 121:39).

Experience—especially religious experience—changes us. These entrances and exits of love and life shed squibs of light on the vigil those of us here on a mortal sojourn keep. Both Love and Death in their turns cause an alchemy all their own, though Love’s be new.

What do we gain in an effort to look along instead of look at?

For the believer there is a possibility of comprehension. The sort where an amoeba “comprehends” its next meal. The same sort in which one comprehends sacramental emblems. They become the living part of one’s being, expressed in revelation as “That which is of God is light; and he that receiveth light, and continueth in God, receiveth more light; and that light groweth brighter and brighter until the perfect day” (D&C 50:24). These squibs thrown off by the Son, though faintly perceived, have a changemaking, alchemic potential. The more “hydroptic” the soul the greater the possibility of an alchemy, and the greater the capacity for Love. For the Christian, and perhaps the Mormon in particular, this new alchemy combines Death and Love in sacramental union such that the creature be new. (Mosiah 27:25–26)

Religion and poetry then blend. Knowledge mediated through symbols of new words, new names, new Light. Metaphor pressed into the mundane layers of meaning. Salvation comes bound up in suffering and perspective. To view life looking along is to view a life divine with all its faults, foibles, and in-betweens. Religion is a living poetry, offering not just light to look at life, but a ray to stand in and look through.

Ari Coleman is principally a husband to Heidi and a father to Zoë. He teaches high school mathematics and is adjunct professor of philosophy at BYU. His research interests include: philosophies of language, mind, and religion, number theory, and music. Ari enjoys hiking, playing euphonium, and dancing with his daughter while singing "Once Upon A Dream."