“The Bible is not merely the history of God's self-revelation to man, it is the history of the making of man capable of receiving the revelation.”1

Those unprepared for life in celestial community, we are told in a revelation named for its peaceableness (the Olive Leaf), “shall return again to their own place, to enjoy that which they are willing to receive, because they were not willing to enjoy that which they might have received” (DC 88:32). That’s a peculiar formulation. Why would anyone refuse a gift? In the language of this particular scripture, the impediment to one’s eternal happiness is not unworthiness or lack of merit—but a choice not to receive it. And the intimation here is that even receiving a gift may involve capacities beyond mere willingness. To receive is apparently more than to passively accept. We might look upon the capacity to receive openly, generously, and gratefully as a lifelong project. William Blake believed we came to earth (from premortal realms) “to learn to bear the beams of love.”2 In Latter-day Saint understanding, this is how agency and grace are reconciled: by our choosing, and learning, to actively receive God's gifts. This may require cherishing the heart behind the gift, and knowing at what cost the gift is made. So how does this apply to our being “capable of receiving the revelation?”

Studdert Kennedy, a frontline WWI chaplain, was appalled and psychically mutilated by the horrors of what happened to human bodies destroyed all around him, bodies he ministered to and often buried. Jesus, he wrote repeatedly, I know and love. But who is this sovereign God who ordains and countenances war? He came to believe that Christ had come to revise our view of God, but we had not received his offering, holding fast to our idols.

“They want to make him an earthly king and armed with a sword. That must be his place if he is the Messiah of God. He refuses it with a shudder. He will not touch the sceptre, and he will not wield the sword. God is not like that. He transforms the whole idea of kingship, and reinterprets it in terms of love and not of material power…Th[at] crown…Christ rejected here on earth, the throne of material power which he refused to mount.”3

Jesus was the revelation we are still struggling to receive, wrote Kennedy.

For Latter-day Saints, revelation generally connotes something very different: words and guidance directed by the spirit to the prophets or to the seeking individual. And the anguished question that we so often find ourselves asking is, why doesn’t (or didn’t) God reveal X to the prophet? Why doesn’t God reveal Y to me?

The fourth-century Christian Athanasius suggests that these two varieties of revelation may be more closely related than we have appreciated. He taught that Christ was the Logos, and as rational beings (logikos), we humans are in his image.4 In other words, Christ is the embodiment of divine understanding, and human beings are like God in being capable of receiving glimpses of divine understanding. But in both cases—with revelation and with The Revelation—our capacity to fully receive Light is slow in developing. When John lamented that “the darkness comprehended it not,” that description of failure captures both types. Doubters could not comprehend his words or absorb the meaning of his appearance in the flesh. So it was in that moment captured in 3 Nephi, when the survivors at the temple heard the voice of the Word twice, and yet “they understood it not.” As understanding pierced their minds, Christ gradually appeared to their sight (3 Ne. 11:4).

The lesson may be that the person of Christ and his voice are inseparable. To know one is to know the other. For the seventeenth-century Cambridge Platonists,

“That which enables us to know and understand aright the things of God must be a living principle of holiness within us. . .Divine truth is better understood as it unfolds itself in the purity of men’s hearts and lives, than in all those subtle niceties into which curious wits may lay it forth.”5

The limited ways in which God’s revelation comes to us is not a consequence of his silence. Slowly, we are being made capable of receiving it. There is an apprenticeship to it. As we cultivate a life of studied reflection (the “pondering” that preceded Joseph F. Smith’s great vision of the dead and Joseph’s section 76), and the “study[ing] it out” to which Oliver was commended (9:8), we prepare ourselves to be receptive to the highest influences. The scriptural injunctions twice to “stand still” (DC 5:34 and 123:17), to “be still” (101:16) similarly are advice to slow down, to impede the automatism of our brains. Telling Oliver to “cast his mind” upon truths once felt (6:22), or urging Joseph to “let the solemnities of eternity rest upon your heart” (43:34), are likewise counsel to remove ourselves from the hectic rhythms of action/reaction and steward those impressions, which are part of an eternal presence already manifest.

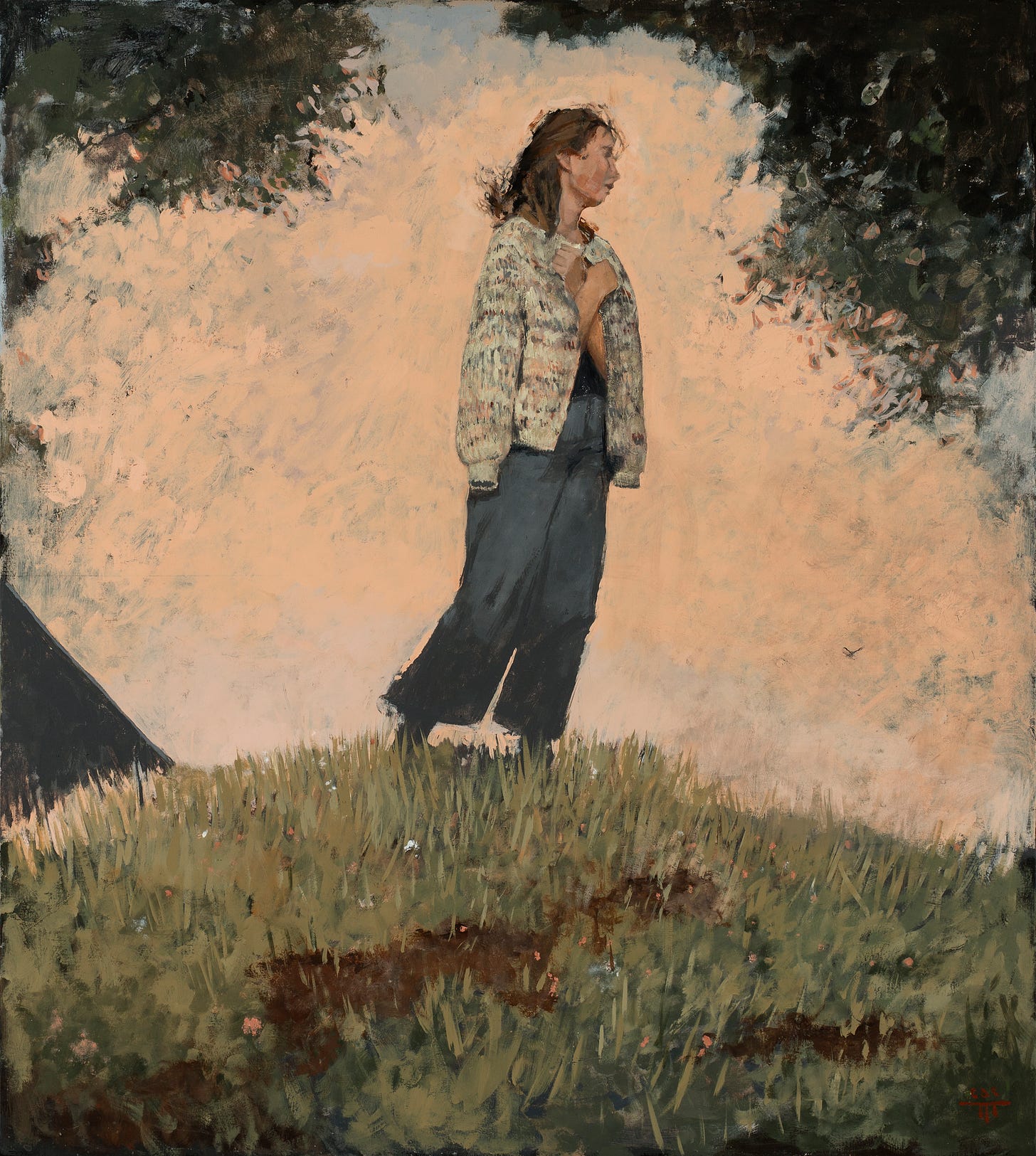

Artwork by Colby Sanford.

To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, first subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."