Latter-day Sikh

An Excerpt

Latter-day Sikh is a biography of Gurcharan Singh Gill, who in 1956 became the first known Sikh to join the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. At the time, Gurcharan was studying mathematics at Fresno State University. Shortly before he left India, he had experienced two tragedies in short succession, losing his older sister, Nasib, and then his baby brother just one month later. In the United States, he found himself wondering what had happened to his siblings and getting into religious discussions with his Christian neighbors about their fate. In this excerpt, we discuss the religious landscape he encountered in Fresno and his path to discovering a new faith.

Part One

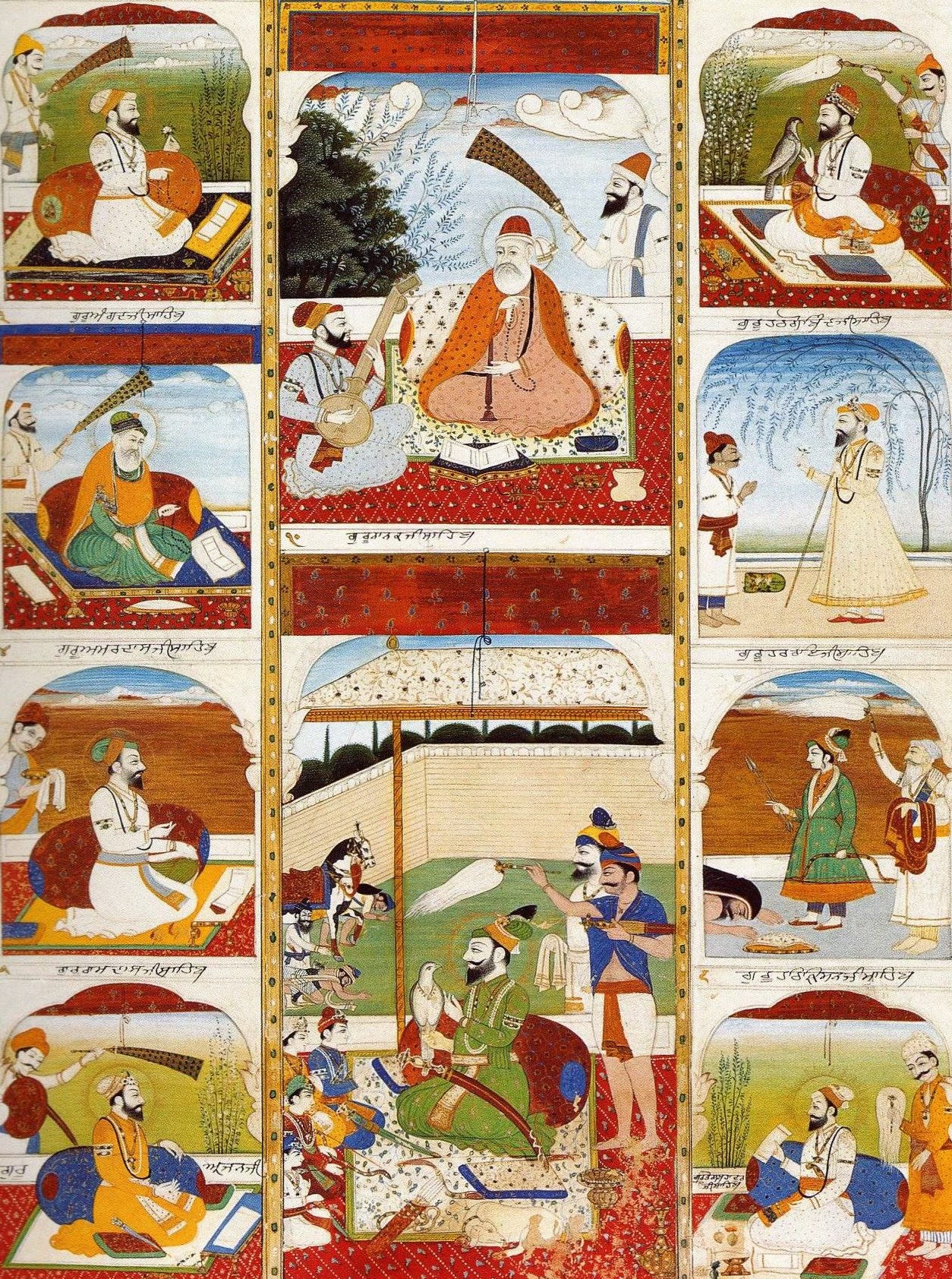

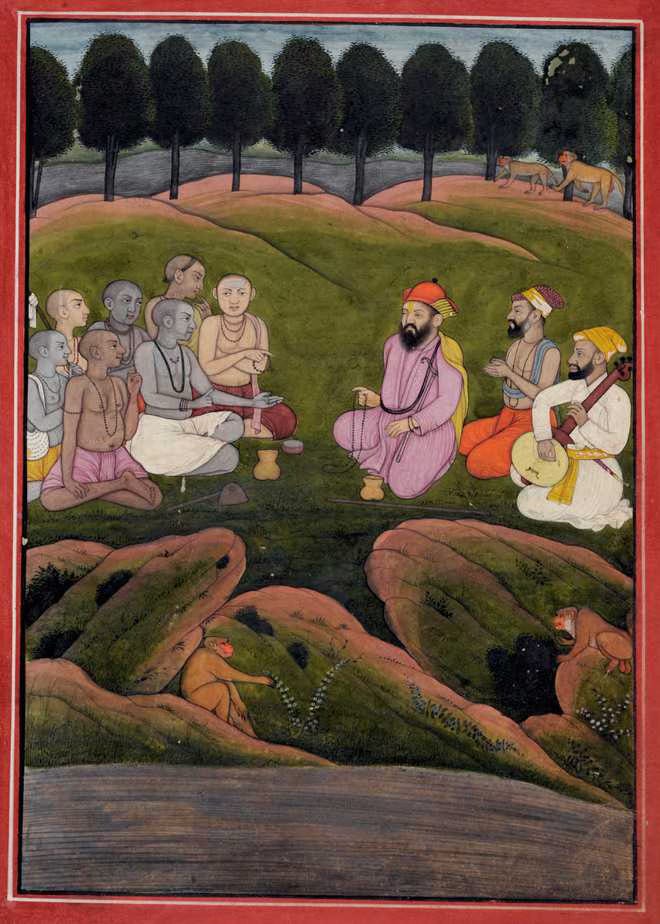

In Sikh thought, the spirit lives on after the body’s death. Like Hindu and Buddhist teachers before them, the Sikh Gurus believed in reincarnation, the idea that a spirit or essence returns in a different physical form. Like Hindus and Buddhists, the Sikh Gurus taught that this cycle of birth, death, and rebirth could be a kind of captivity, and that life’s purpose was to move on. Just as a drop of water eventually returns to the sea, they believed, a human spirit is a piece of God and is destined to merge back into God.

But for Gurcharan, that idea was not totally satisfying. As he thought more about death and the people he had lost, he would get a sense sometimes that Nasib was still there. That she existed as herself, not having lost her identity by merging back into God or moving into another physical form. What did that feeling mean?

During his second year of college, Gurcharan decided to find out. “On Sundays, I started to go to some of the churches in Fresno,” he remembered. “Buses were common, so transportation was no problem.” And religious people were mostly happy to talk with an intense young Indian who showed up at the doors.

Gurcharan became friends with the Catholic priest who ran the faith’s programs for Fresno State students. They would have long discussions about Christian teachings, life after death, and the role of the sacraments. Gurcharan also talked with different Protestants. Across denominations, many Christians were happy to tell Gurcharan about how he could accept Jesus and be saved. But he wasn’t asking for himself. He wanted to know what had happened to Nasib and Ajaib. Because they had never been Christians, most of the people he talked to were unsure how to answer. If salvation depended on accepting Jesus, one conclusion was that they had missed their chance. To Gurcharan, that idea simply didn’t make sense. He believed the Sikh Gurus’ image of a just God. He continued to press people for more details about his particular case. Surely it was not so unusual. More than half the people in the world had never been Christians. What was the purpose of life for them?

During this time of religious searching, Gurcharan began spending more time with a fellow student named Larry Hettick, whose brother was studying to become a minister in their Pentecostal church. Larry and his family were good people who looked for ways to serve others and had an open door for anyone who wanted a comfortable place to be. Gurcharan sometimes went with Larry to his church’s Sunday school to consider different ideas and pose questions. Because people often dressed in formal clothes for church meetings, Larry’s mother even sewed Gurcharan a nice jacket to wear. Her actions reminded Gurcharan of the faithfulness and thoughtfulness of his aunt Gian Kaur. One week, a missionary from Larrry’s church was returning home and the Hettick family was hosting a reception for him. In that more informal setting, Gurcharan got talking with Larry’s mother and shared his most pressing questions. What happened to people who had never accepted Jesus or been baptized? She thought about what he was saying, then gave him an unexpected answer. “You should talk to the Mormons,” she said. “They have ideas about that.”

Part Two

That Sunday, Gurcharan went to the address a friend had given him and slipped into a seat in the very back row of the chapel. It was a “stake conference.” He did not realize that a “stake” was made up of many different local congregations, called wards, and was surprised when the building filled all the way up. Soon, the service began. The hymns, the speakers, and the atmosphere all gave him a sense of peace. Then the stake president stood up to speak. His topic was the plan of salvation. He started by describing the premortal life, detailing how God created His children as individual spirits who had lived with Him before we came to earth. Few Christian faiths believed in a premortal life, but for Gurcharan, the concept rang true. In India’s Dharmic faiths, too, existence began long before birth.

The speaker continued with a description of God’s plan for mortal life. He said that as God’s children, human beings were here to learn and grow, to be challenged and refined. Only some would hear the gospel, the speaker said, but all would be able to develop their divine nature through their experience and the truths they had. Then, the speaker talked about a spirit world, where we go after life. He explained that the gospel could be taught to those who had died and how temples connect the living and the dead and allow the spirits of people who have died to choose to receive baptism and further rituals like a sealing to their families. He talked about resurrection, different kingdoms of glory, and how each individual will have eternal life. To Gurcharan, this plan of salvation felt right, almost like something he had known before. He felt these new truths burning inside himself. He had to know more.

After the meeting, Gurcharan’s head was still spinning with all the new ideas he had heard. In the foyer, he saw a thoughtful-looking boy, maybe twelve years old, and he thought about the story he had just heard about the young Joseph Smith asking God for wisdom. As he looked at this boy, he also felt a sense of recognition. Even though Gurcharan had just heard Latter-day Saints believed in a premortal life, it was easy for him to believe that the two of them had met before they were born. He felt like he needed to introduce himself now and find out why their paths had crossed again.

The boy said his name was Jan Johnson. He introduced Gurcharan to his brother, Kim, and to his parents, Norman and Gretna, who were serving as stake missionaries. Gurcharan immediately began asking questions about their beliefs. He wanted to know about Jesus Christ, the Atonement, and exaltation. Norman and Gretna were eager to answer. Jan contributed freely to the conversation. Although he was young, he was already firmly rooted in a knowledge of his faith.

The Johnsons invited Gurcharan to follow them home to learn more. He accepted the invitation, and the Johnsons asked four full-time missionaries if they’d like to come, too. While Gretna fixed lunch, she played a record that told the story of Joseph Smith’s search for truth and calling as a prophet. Like the conference speaker’s description of the plan of salvation, this story of a modern prophet felt both foreign and familiar to Gurcharan. He readily agreed to return to the Johnson’s for a series of lessons.

Learning about faith in the Johnson home felt natural for Gurcharan. The family would gather to teach gospel principles. Gretna was an active and experienced local missionary who had already helped many people, including her husband, find new strength and meaning in the restored gospel. She and Norman led the lessons, but their sons often answered difficult questions and asked things that prompted further discussion. The boys seemed to genuinely enjoy the discussions.

When Gurcharan came over later in the evening, the boys would sometimes sneak down from bed to listen in and have to be sent up to their rooms again. Though Gurcharan was several years older than the boys, he felt like a child in the gospel. He was learning from the scriptures and other books, but also just from watching the family. The Johnsons were down-to-earth, hardworking people like Gurcharan’s own family. Norman worked with his older brother in a small business, picking up laundry from different shops in town to wash and return. Gretna was primarily a homemaker. Like the family of his Pentecostal friend, Larry Hettick, the Johnsons were friends as well as teachers. While Gurcharan was in their lives, they were concerned about how he was doing and looked for ways to help him. That warmth was its own message.

But intellectual learning was also important. In California, Latter-day Saint missionaries most often taught Protestants, who shared core concepts but understood them differently. Teachings of latter-day prophets and passages from the Book of Mormon helped them see old knowledge in new ways. But for Gurcharan, the Bible itself was new, stories about Jesus still unfamiliar. Along with getting to know four volumes of Latter-day Saint scripture (the Bible, the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price), Gurcharan worked his way through books like James Talmage’s Jesus the Christ to understand the faith he was being offered. Idea by idea and insight by insight, the new pieces fell into place.

To him, the restored gospel drew on divine truths that went beyond the cultures of ancient Israel or modern Latter-day Saints. “I felt that the new doctrine I had learned built upon truth I had already learned through the Sikh teachings I was raised with,” he reflected. The Sikh sense that we are all part of God fit in with Latter-day Saint teachings about humanity’s divine nature. The details were different in important ways, but the core recognition of a spiritual reality in every living being was the same.

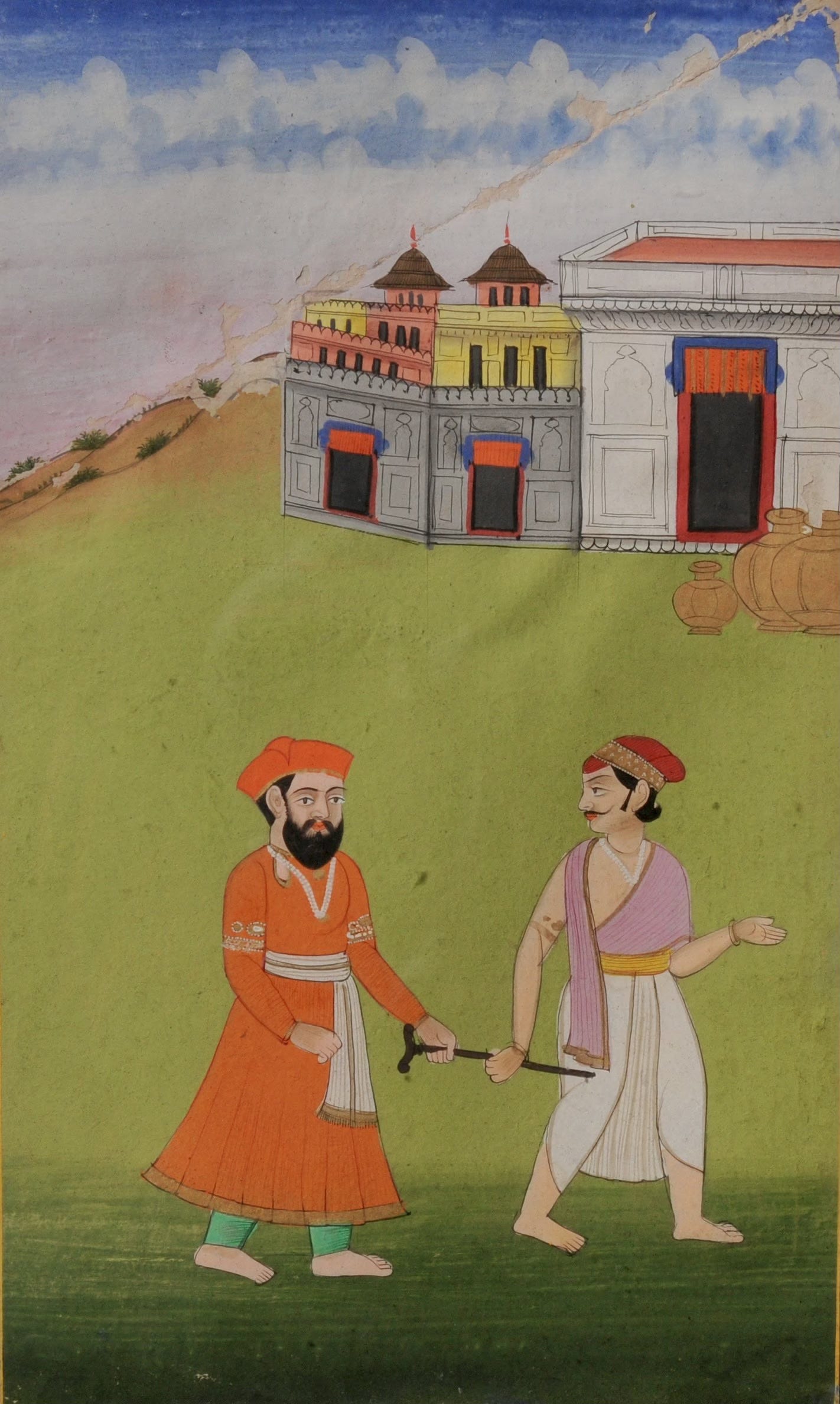

That didn’t surprise Gurcharan. Guru Nanak’s message began with an encounter with God. So did Joseph Smith’s. Guru Nanak had embraced family life and taught that the life of a householder, more than the life of an ascetic, was the path to godliness. Joseph Smith had likewise elevated family relationships, placing them at the center of time and eternity. Guru Nanak had invited people to leave behind caste prejudice and join together in a sangat, or company of believers, where individual members could serve one another and model a new kind of social life. Joseph Smith had organized Latter-day Saints into wards, a term that once described a neighborhood in a city, and called people to serve each other within these units.

Both Sikh Gurus and Latter-day Saint prophets had drawn on the spirit of their faith to build cities. As he learned, Gurcharan began to think of Joseph Smith as his “eleventh Guru,” sent by God a century after Gobind Singh’s death to bring a new message and gather a new community. It thrilled him to think that the line of Latter-day Saint prophets continued to the present. Gurcharan’s name meant “one who followed a messenger from God.” He would do so, even if it meant stepping beyond the path of leadership from the Sikh scriptures and the Khalsa left after the last Sikh human Guru’s death.

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

Art from the Kapany Collection. Personal photographs courtesy of James Goldberg.