“ . . . History may be servitude, History may be freedom. See, now they vanish, The faces and places, with the self which, as it could, loved them, To become renewed, transfigured, in another pattern.” —T. S. Eliot, “Little Gidding,” from Four Quartets

The autumnal chill wends its way up the dilapidated stairwell, following us through the darkened doorframe and into our Soviet-era apartment. We strip off our galoshes, raincoats, and gloves. We laugh as we talk about a funny interaction that morning. We had both been scolded by a Ukrainian babushka—me, more particularly—for the infraction of not properly wearing hats.

Why is she not wearing a hat? the wrinkled woman had asked me, pointing at my companion. It is for her health and you are the older one—why isn’t she wearing a hat?

I had shrugged—She doesn’t want to, I had replied. How was I to force someone to wear a hat?

“I just don’t like hats,” my companion says nonchalantly, as we move into the kitchen to heat water. A rainy November morning requires herbal tea.

The kitchen, like most of the apartment, is old. How old, we are not sure, not by historical nor by mission age. One of our neighbors says that this block of apartments stood before World War II. When we see him in the dvor, in the apartment courtyard, he regales us with stories of his grandmother—how she survived the Nazi occupation, how this small corner of eastern Ukraine was full of death, destruction, and life.

My companion exits the kitchen momentarily to go to our bedroom to grab milk, where, strangely, the refrigerator rests by my headboard. Who made the decision to put the refrigerator in the bedroom, I will never know, but there it stands, making our bedroom an odd extension of the kitchen, home to both bagged dairy products and morning prayers.

This apartment is both in and out of time, with and without history. I only know the missionaries who came right before us—two elders who had written detailed “whitewash” notes before they were transferred out of this area and moved on to other fields.

And perhaps the term whitewash is apt. With no one to tell of beforetimes, we are free to make our own stories, our own history here. We are the first sister missionaries to live in this apartment, to use this kitchen with its frosted window looking out over a road named after a revolution, leading to the prison. This is my companion’s first area, her first apartment—the beginning of her story, full of possibilities. For both of us, it is a new city—a new start. As the first sister missionaries here, in a strange way, it feels like we are the first women to ever live in this apartment, which of course cannot be true, can it? But in the golden autumn light, we feel like the only ones, disconnected from the larger past, while preparing breakfast together in a small corner in eastern Ukraine.

And still, this space contains multitudes—more than I can recognize as I sit down at the kitchen table, turn on the CD player, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir intoning softly. The cupboards are full of missionaries past: of ranch dressing packets and taco seasoning from thoughtful Cache Valley mothers, of Taylor Swift calendars, of Ensign cutouts of a blond, European-looking Jesus posted onto the wall . . . walls that once-upon-a-time might have held a portrait of Lenin or Stalin, or else listened in as trusted confidantes ridiculed Brezhnev while sharing the literature of dissent with a side of kvas and shelled sunflower seeds.

My companion and I work in the kitchen, lost in our own narratives and crafting narratives for those we try to serve. Will Tomara agree to read the Book of Mormon? Will Lena finally answer our phone calls? Will Sasha come to church? Mornings in the kitchen are for hope—two American girls, far from home, happy in their companionship and dreaming of miracles, dreaming of Zion in this eastern land. How will Zion be built? We are not exactly sure, but we believe the promise that willing hearts prosper in Zion. If we are anything, we are willing.

Not all mission mornings are like this. They simply cannot be. Another companion of mine frequently recited the mantra, “It won’t always be like this,” to remind me that even bad times end. My own experiences as a missionary testified of ups and downs: of wounds inflicted by other missionaries, of crippling homesickness, and of disappointment after disappointment; but also of generosity, of good Ukrainian Saints wiping tears away from my eyes, of golden fields of Ukrainian sunflowers against a striking blue.

It won’t always be like this; nothing lasts forever.

The leftover missionary paraphernalia we discover while cleaning out dusty drawers also speak of this almost Newtonian law:

Elder, penned one missionary to another, I know you’re having a hard time, but just hold on. And remember these lines from Jimmy Eat World:

“It just takes some time You’re in the middle of the ride, Everything, everything will be just fine Everything, everything will be alright, alright.” Love you, man.

Finding the note feels like trespassing. I know both elders (though I do not know when or even if they served here . . . perhaps this was a note left behind during a missionary exchange). I know their reputations, whether good or bad. But the note softens me. It was written to a missionary who had, months ago, hurt me. A missionary who I felt had turned a blind eye to how my then-companions bullied me. I still cannot forget what happened that summer, and I am not ready to forgive, but something shifts inside of me, and for a moment, I see him not as an antagonist, but as a fellow wandering, hurting soul. I put the note down, embarrassed to infringe on this offering of friendship and afraid to delve into my own fears.

How will Zion be built? Again and again, the Lord says that Zion is the “pure in heart,” but my heart is far from pure, however willing. My willpower proves powerless against the contradictory desires of my own heart, let alone against bridging the chasms that divide human experience.

Theoretically, aspiring to the ways of the citizens of Enoch’s city inspires me to understand the poetry inside of others, to see them as my brothers and sisters rather than strangers or enemies. In reality, I balk at throwing away my weapons of war. My own avarice, others’ pride, and the ignorance which blinds us all mock the promise of Zion.

And yet, and yet. I still receive glimpses that unity and love are possible. I find them unexpectedly: in a letter not addressed to me, in a November morning in Kharkiv, Ukraine, in a kind word on the street: “I am not interested, girls, but I admire you for being here, all the same.” It won’t always be like this. So I savor the morning, trying to hold onto a moment that quickly turns into memory.

Memory and history are fickle. The moment I think I understand them, they slip out of my grasp, surprising me with their audacity, reminding me that they refuse to be owned. To assume that memory and history are fixed entities is dangerous, but it is also dangerous to ignore them, or to let someone else tell our stories for us. The stories we tell about ourselves, our nations, our families—they matter.

“History may be servitude, history may be freedom,” wrote T. S. Eliot in “Little Gidding,” as part of his magisterial Four Quartets. It is a sentiment which resonates within me for reasons beyond my understanding, something I feel more than I know how to explain. Perhaps it is because of my own history of seeing how the stories I tell myself can blind me to or remind me of responsibilities to those around me; perhaps it is because of a personal belief that we cannot change the future unless we confront the past.

Years after sitting in that kitchen in Kharkiv, I will sit with a man (a man who will become my husband) and watch a Chilean film Nostalgia de la Luz (Nostalgia for the Light) about the varied searches for truth in the Atacama Desert: the search for the mysteries of the cosmos in the desert sky, and the search that mothers, wives, and sisters undertake, looking for the remains of disappeared, assassinated loved ones in the desert ground.

“The light we see from the stars is actually hundreds of years old,” explains a Chilean astronomer. “The light we see is already past. The present is so brief. Blink, and it disappears.”

The light we see is already past. Memory is alive, pulsing through us, connecting the present to the past, but also decomposing the second we blink away from the present. History interprets what is left from the past, analyzing the memories of others, trying to explain patterns, processes, and change over time. History may be servitude, history may be freedom.

Right now, the present filters my memories of Ukraine. I cannot think of that sunny kitchen in Kharkiv without wondering if it, too, has been destroyed. I remember the people of Makiivka, of Kharkiv, of Donetsk, and Mariupol, the kerchiefed babushki, the smiling families, the coal-stained miners, the faces I knew and the ones I did not, and I wonder what has happened to them—wonder what is happening to them.

I cannot remember walking through the spring streets of Mariupol without seeing them now—destroyed, bombed out, kitchens cut in half. My memories are like a children’s science book with transparent pages stacked on top of each other, the better to see the inner workings of a clock or the functions of the human body systems. The last page shows simply a skeleton, but add the next-to-last transparent page on top of the skeleton, and you see the nervous system. Add the next, and you see the organs, until page by page, you arrive at the beginning, with a picture of a smiling child, kicking a soccer ball.

Now, I see the skeletons. I see the bare bones of apartments, I see demolished maternity hospitals. But go back, and I can see myself on those streets, in those apartments, with those people. Go back further, and I can imagine those streets during the Soviet Union under Nazi occupation. Go back further, and they are no longer streets, but fields. How does God hold the past, present, and future simultaneously before Him, like a river of glass? And how does He hold the hurt we inflict on each other, on ourselves?

I cannot hold it all, but I do have glimpses. I see it as my own memories spread before me, painted with brushstrokes of past, present, and future; I feel it as my remembrances of places and people I used to love, as my past and present experiences with them. My hopes and fears for the future transfigure and renew their faces. I remember a moment at Little Gidding, the very parish which inspired T. S. Eliot’s musings on time, memory, loss, and love. For an afternoon, I traveled with Sam (the man with whom I had watched Nostalgia for the Light) and his good friend Neil through the summered English countryside.

Sam and I were not yet engaged, but very much in love, and eager to share beloved memories and places with each other and create new memories in those beloved places. Cambridge, England, was one of those places for both of us, and a place that Sam wanted to introduce to Neil. I sat in the backseat as we drove from Oxford to Cambridge, listening to Neil muse about resurrection, watching the fields shift between gold and green.

We took a detour to Little Gidding, a village in Cambridgeshire with a small Anglican chapel. This chapel had served as a muse to many poets, and we passed that way because of what we had read, and what we had felt as we read.

The oak-paneled walls of the chapel gave a rosy feel as the June sunlight pierced through the stained-glass windows. A hush came over our conversation as we read embroidered transcriptions of poems and epitaphs:

You are not here to verify, Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity Or carry report. You are here to kneel Where prayer has been valid.

We stood in a holy place, a place where our prayers mingled with the prayers and supplications of countless others throughout the ages, from wandering kings to determined tourists. This place was not only holy because of the past, but because we, ourselves, living and breathing, with bonds of friendship and love stood in that place with our own hopes, fears, and dreams. We stood in a place of timeless moments, within walls which had witnessed both transcendence and banality.

Later, the three of us took a carefully crafted selfie outside of the chapel, trying to create a memento, trying to hold onto the present already slipping away. I could not know then what the future held. I could hope that I would marry the man who had his arm around me, but I did not know what specific joys and sorrows would follow us; I did not know that that summer would be the last time I would see Neil in person; I did not know how to love either of them the way their souls deserve. I loved them as much as I could at that moment, and I hope I love them more now.

Again, I turn the page of my book of recollections to Ukraine (a place which materializes often in my kaleidoscope of memory), to a place I loved as I was able in the moments I lived there, to a place I hope I love more even now. If I open to a specific page in the summer of 2012, I find a five-story Soviet apartment building, most likely built during the time of Khrushchev. If I open the next translucent page, I see myself there, a twenty-one-year-old missionary, sunburned, flea-bitten, and deeply sad, kneeling in a dusty Soviet kitchen, with July sun streaming through floral curtains, crying out to God in despair and brokenness, feeling the impossibility of serving a mission, of finding God in faces made both familiar and unfamiliar.

And though one might not see the change from that page, I know what I felt that day, broken and worn, carrying a weight of sorrows and expectations. I know the song I heard, whispered through mountain canyons, across the Atlantic Ocean, over sunset plains, into a post-industrial Ukrainian city, the words which filled a missionary’s heart with the awareness of God: that God loves broken things, broken people, broken me, that He is the lover of souls, the comforter of Zion, and the healer of her lonely, wasted places.

Megan Armknecht is a writer, historian, and PhD candidate in history at Princeton University.

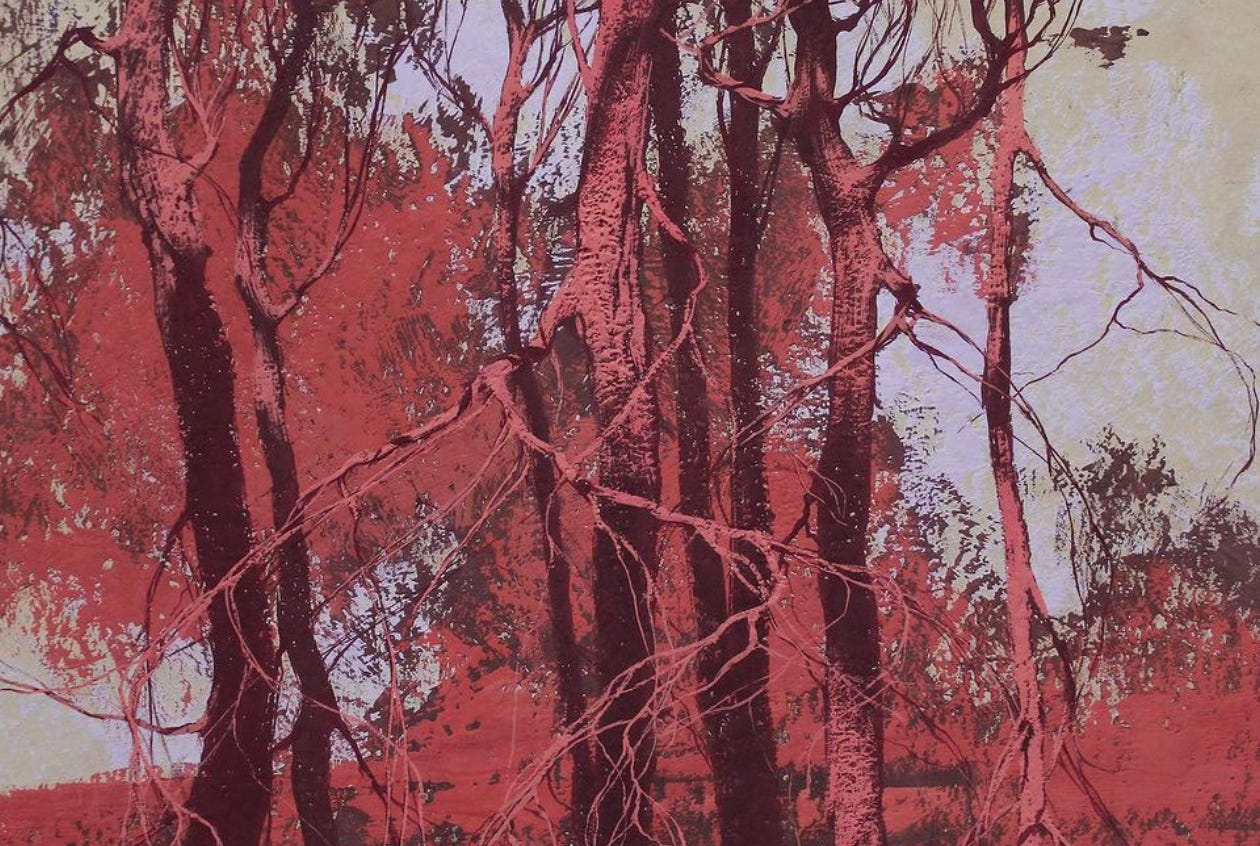

Art by Artem Rogwoi.