The wintering sun is low but not yet gone as I step into the old white steepled building full of Joel Church’s paintings. Light seeps clearly through the cold open room, spreading into corners, revealing dozens of darkly painted canvases bearing human forms. There are few people inside, making each voice distinct and each footstep noticeable—Belchertown, Massachusetts, is quiet that way. The original pews have been removed, the simple wooden floor cleared of everything but paintings and sculptures. Reverence fills the emptiness. The church, though tall on a hill, is shrouded by dense, unleafed November trees. No one passing on the two-lane road below would know what this chapel holds.

Inside, artist Kirk Richards welcomes those who wander through the doors. He acquired this church years ago to serve as a studio and, now, as an occasional gallery space. “Make yourself at home,” he tells everyone. It is the type of home everyone present is likely familiar with; most people, including myself, are here because they know Kirk’s religious work and are at least tangentially connected to the Christian faith his subject matter typically converses with. But this show, his first gallery presented by his second artist name, Joel Church, is different—instead of angels and Jesus and God, his new work delves purely into “the greatest of all forms: the human figure.”

Blue ink transfer drawings accented by brief strokes of white paint cover a wall near the entrance. The papers are mostly the size of small notecards, collaged with fuller pages and a few canvas enlargements that mimic the pulsing, bleeding effect of transferred ink. All blue. Dark, inky blue. Male and female figures walking, resting, presenting their bodies to the viewer and drawing their limbs close. Marked in the corner of each piece is a small silhouette of a steepled church. Not a name spelled out in letters, but a signature in picture form.

In a small room off to the side, separated from the expanse of unclothed figures, hang two depictions of a haloed, pink-robed Christ surrounded by indistinct crowds of people draped in painted cloth. The colors are pastel, neutral, warm; the shapes are abstract, blurred. In one, Christ lifts a cup; in the other, he gestures to a flying dove. Both pieces, along with a framed landscape propped between them, bear the initials JKR in blocky print. “I’ve been doing religious work—paintings of Jesus and angels—from the moment I had skill enough to finish an oil painting. I return to themes of healing and teaching over and over again.”

Kirk has always been called by his middle name alone—both signatures are departures from his everyday persona. His original artist name did not require significant thought; the inclusion of his first initial was merely used to differentiate himself from an older painter in Texas who shares the name Kirk Richards. Once he began exploring markedly varied themes, Kirk created the name Joel Church to distinguish the intentions guiding his work, though the separation isn’t always clear. “One body of work always wants to spill over into the other, and vice versa.” Attempting to categorize the work under each name, he calls the work by J. Kirk Richards “overtly religious and urgently active and reactive to my immediate surroundings, contexts and roots, mostly with clothed figures.” In contrast, he describes work by Joel Church as, “searching for something beyond the immediate contexts,” though unsure of exactly what paths it might explore. “So far, the human figure has been a central component. Perhaps too central. Time will tell.”

Mostly. Mostly clothed, always figures. Despite the necessity of studying the human figure to produce life-like art, Kirk has sometimes been criticized on grounds of religious propriety. He responded to his detractors in a 2012 blog post titled, Why are you painting those naked ladies? Or, what makes me think I can go to a nude drawing session on Saturday and then go to church on Sunday? Describing a figure drawing session at a studio in Park City, Utah, Kirk recalls his first experience as a young artist drawing a nude model. “She stepped onto the platform. She stood there, naked. I started drawing. I began the overwhelming task of laying values, lines, and marks on my page—desperately straining my brain to correctly record proportions, anatomy, edges, divisions of light and dark.” Ultimately, the experience was not sexual in the way his personal naivety and community’s religious framework had led him to believe. At a later drawing session, an older artist further molded Kirk’s philosophy regarding figure models by suggesting, “The human body is not inherently sexual.” After years of artistic practice, Kirk believes, “We were created in the image of God—which image I believe should be respected. I have no problems reconciling my faith with nudity.”

The issue with clothing, Kirk explains, is that the style and draping pattern of cloth immediately dates a piece of art, assigning it a certain time and place in history, which he often tries to avoid. “The figure itself, whether nude or clothed, speaks through gestures. The bend of the waist, arm, leg, hand—those gestures begin to tell a story. I want that story to be universal, archetypal, or separate from physical time and place. Figurative gesture is key in my work.” His Joel Church paintings, sculptures, and ink tracings speak through stance and shape.

In 2017, Kirk displayed his art show After Our Likeness at a gallery in Provo, Utah. An interpretation of the Biblical creation story, the pieces depicted “God as a woman and a man working in tandem to make the world and its inhabitants.” In addition to the acknowledgement of female deity and portrayal of sacred beings as semi-nude in order to transcend the human concept of time, the figures bore skin tones that corresponded with their changing landscapes: greens, purples, browns and blues. Some viewers critiqued the varying skin tones and his attempt as a white artist to represent race, saying some of the paintings resembled photographs of slaves. Kirk apologized for any pain caused, but pointed out that the purpose of this art show was to dismantle the white Mormonism version of the creation story and offer images all people could relate to. For him, the universality he was seeking necessitated varying skin tones and abstract nudity. “I admit that the show comes together at a dangerous intersection—where race, religion, art and the body meet,” Kirk wrote, “but I humbly suggest that this show needed to be done here and now.”

Kirk’s primary gallery and studios are in Utah, close to where he studied art as an undergraduate student at Brigham Young University. When he first expressed interest in focusing on religious art as a student, professors warned him against specializing in such a niche, but Kirk could not be swayed from his initial impulse. He continued creating what he wanted to create. Though he doesn’t paint for any specific church, much of his artistic community exists within the context of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

While many of his paintings have been licensed by the LDS Church and other denominations around the world, not all of his work has been so readily used by organizations, especially when artistic choices depart from standard portrayals of scriptural accounts—giving angels wings, or placing Christ in the shadows. Margaret Olsen Hemming, an LDS art curator, explains, “Church-approved images of Christ and Heavenly Father skew heavily toward depicting white, European-looking men in an illustrative style.” If Kirk’s only goal was to create images that a specific church would be willing to use, most of the paintings that resonate most significantly with people would never have been painted. He urges other creators to “make artwork for God’s children. Having pursued my own vision of what I want to communicate to God’s children, my images hold a power that orthodoxy would have squelched.”

Kirk’s numerous rainbow paintings signed JKR are a tangible example of this unorthodox power. “My first rainbow painting was Jesus Said Love Everyone, depicting Jesus with embracing arms, in a rainbow robe filled with people. The painting had seven sides, a number that in religious symbology means perfection.” Disagreeing with the stance others of his faith took towards the LGBTQIA+ community, Kirk found inspiration and hope in the song children sing in church about loving everyone and treating all people with kindness.

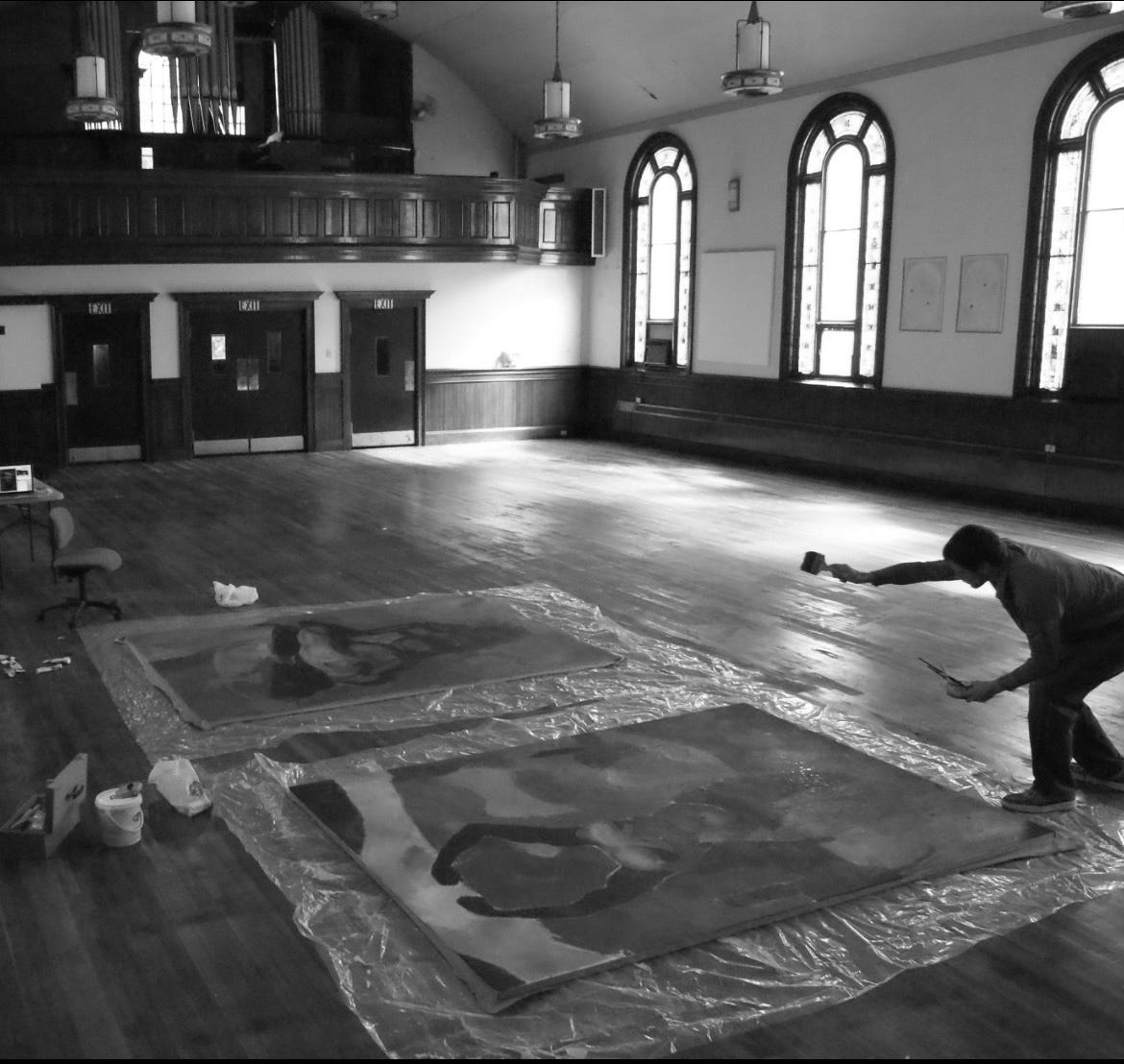

One irony begs to be questioned: The work presented under Kirk’s second artist name, Joel Church, purportedly leans less religious than the work signed J. Kirk Richards. So why is it housed in a church? “I wanted a space where I could work on large-scale art pieces. Churches were, and to an extent still are, relatively inexpensive to purchase in the northeast. I looked at non-church spaces as well, but they didn’t appeal to me in the same way. The idea of a sacred space containing art excites me.” In the future, Kirk hopes to create multiple art chapels—transforming old churches into art studios and galleries.

When questioned theoretically, the line between the art associated with each of the two names remains blurry. Yet up close, distinctions become clearer, especially in the context of Joel Church’s first art show, consisting of pieces congruous in texture, subject, and motif. “There are a lot of themes in these about values or virtues, and monuments, and also about the transitory nature, the limited lifespan of all things.”

Standing in front of the blue ink drawings, I inquire how much time he has spent creating the pieces being shown. “I started in this space nine years ago, so a lot of these, particularly the paintings on linen, it’s been almost a decade. And some of them still aren’t done, embarrassingly. I want them to have a similar finish, not with colors, but with the texture and the oil layers, as that one right there,” he says, pointing to Glass Ceiling, an expansive linen canvas that claims a central spot at the front of the chapel where the altar once might have stood. The painting is dark, metallic, faded yet boldly defined. A statuesque female figure lacking head, neck, and half her legs, floats upward in a strong stance. Hips wide and sure, belly full and firm, breasts draping the ribcage with softness, muscled arms raised defiantly with clenched fists that pound against streaks of light, shattering blueness. She is clothed not in cloth, but in metal skin. Defined not by time, but by lack of timid gesture.

While the canvases have been worked on over the past decade, the images crafted on smaller panels of copper have emerged only in the past six months. “I was trying to think how I could do something that works with this body of work, but faster. I’d come out here, make a little bit of progress, then go home. Two-thirds of the copper ones were done while I was here in the last four weeks. The textures are actually chemically created patinas, so it’s not like the paintings, noodling to create the illusion of a patina, it’s actually the chemicals doing the work.”

The process starts with painting the copper panels with monochromatic oil colors, then creating a mixture of red wine vinegar, plant fertilizer, and salt to effect chemical changes on the piece. “I lift the panels off the liquid so it’s swimming above the soup, then I put some of it on the painting, and I pour on solvent and salts, different seasonings.” After the chemicals alter the texture and shape of the original painting, he’ll use more paint to add spaces, colors, and tones.

I wander through the church, standing before each figure. They can’t see me; most of them don’t have heads. Some have blurred faces, or eyes of painted stone or metal. They are statues and monuments, with life and movement bound and pulsing. In Resistance, a male torso bears the weight of a heavy stone on his shoulders. In Nurture, a father cradles an infant close to his chest; in Mother and Child, a woman wraps a young body in trustful arms. In Boundary, a defined female figure propped on a work table bows her head to the right, body soft and rounded, arms either broken off or not yet built. A reaching hand floats at the end of an imagined limb. The color is green, as if already oxidized. Paint is splattered and a patch above the left breast appears unfinished, reminding me this is a painting of a statue, not a statue itself. Despite the repeated translations away from true human form, I recognize my own body in hers. Bloom depicts a coppery bare-breasted woman whose skin appears warmed by living blood, red hair loose, lips and collar bones defined even as the eyes retain abstractness, flowers gathered around her waist.

A few people gather with Kirk by a wall marked by the outline of a larger frame that used to hang there long ago. “Venus is quite white,” he says, referring to a piece whose lighter coloring adds significant contrast to the copper hue, featuring a standing female figure, her weight grounded in one foot while the other hovers, arms ending at the shoulders, torso ending at the neck. He points to the framed copper plate on the wall closest to us. “Sometimes I just try to do almost monochromatic but not totally, with some greens, so it’s a little cooler than the copper, kind of that pinkish and white. I let the oxidation bring the cools in, and then sometimes I paint some green on top after that process to do some subtle shifting of things to finish it off.”

Amy, Kirk’s wife and partner in the art business from the very beginning, joins the group. I ask her if she has a favorite piece tonight. “There isn’t anything he does that I don’t like, but I’m biased. There’s the Glass Ceiling, of course, which is great for us women.” She raises her arms in fists to match the figure’s stance. Amy is an artist too; she’s had art shows of her own. “Now it’s more of a hobby. I went back to school and work as a therapist now, but I’d like to do something with art therapy,” she says. She’s visited this church every other year or so as Kirk has come to work on these pieces. I shiver despite my coat, and Amy comments on the coldness of the large open chapel. “Sometimes he’ll go in that corner room and shut the door, let it warm up and paint in there.”

In the fresh absence of the sunken sun, the dull green and brown patchworks of the stained-glass windows suddenly match the coloring of Kirk’s work. When a woman returns to the wall of blue ink transfer drawings to decide which one she wants to purchase to take home, I follow. They are small enough, simple enough, to be affordable pieces of fine art. We point out our favorites, some of our choices overlapping. She is drawn to the folded poses, “in part because the Joel Church signature in the corner is so clear. And I love her. The confidence,” she says. I am drawn to the figures pulling their knees close to their chest, imbued with cozy safeness. “I was raised in the church,” the woman tells me, “and reclaiming the feminine form and bodies as good has been such a growing space.” I voice my agreement. We pull our favorites from the wall where they all dangle from tiny binder clips on thin nails. I choose two: both side profiles, one of a woman walking forward with a sense of quiet sureness, her arms drawn slightly back in motion, the other of a woman kneeling with her arms raised to the heavens. They are blue. Dark, inky blue, with a faint blend of pink in the white painted accents. They feel scripture-paper thin in my hands.

Kirk unclips the drawings and tapes them into a folded postcard, guarding them from potential harm, while continuing his conversation with those around him. “My paintings have always prioritized the poetry of scripture over dogma. To me, dogma is the main thing that makes scriptures unappealing. Remove the dogma, and scripture is full of immense beauty. Do I care about how I’m perceived? A little bit. I’ve worried more about sharing on social media lately, but I’m not sure if it’s because of concern about what people think of me. It might be that I’ve been relishing quietude lately, when my brain and heart can rest. There are a lot of things I can’t reconcile, so I live with tension. I’ve been embracing differentiation theory, which is about how to belong to yourself while also belonging to another person or group. I am myself. I am not my country, family, or church. I participate within those groups, but I am different from those groups. That’s about all I can do to reconcile things at the moment.”

Outside, the early night is stark and brittle, poked by scraggly bare-leaf branches. The tall, rounding windows pulse warm with chapel light, transferring reverence to the darkened air.

Fleur Van Woerkom is a lover of earth, art, movement, and stories. She is currently studying writing at Columbia University.

Art by Joel Church. Photos by J. Kirk Richards.