On days when the world is too much with me, I retire to the right transept of Stanford Memorial Church.

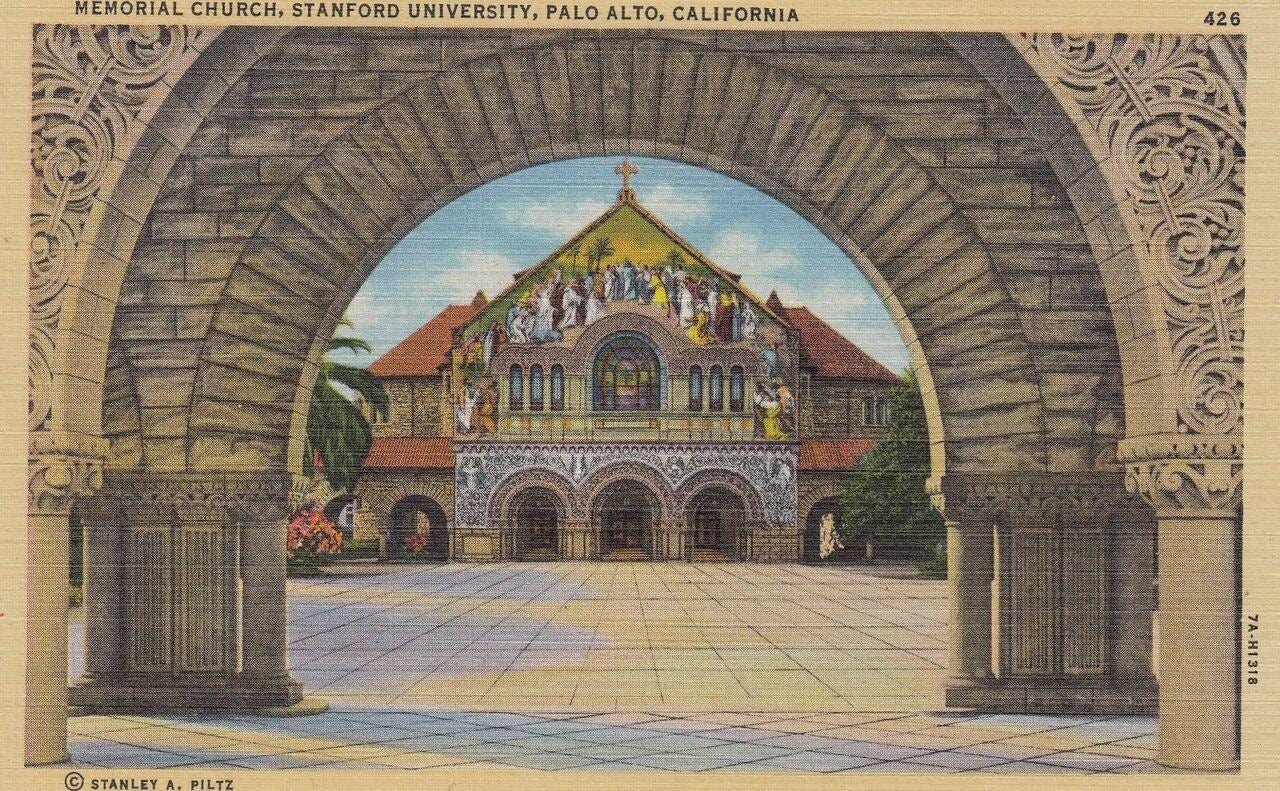

Stationed at the head of Stanford’s main quad, Memorial Church dominates campus, fulfilling Jane and Leland Stanford’s desire for a church at the center of the University to symbolize the education of the soul and not just the brain. For twenty-nine months during the worst of the pandemic, Memorial Church—known affectionately on campus as MemChu—remained closed, opening gradually for special events and then, finally, in September 2022, throwing open its doors to allow visitors at all hours.

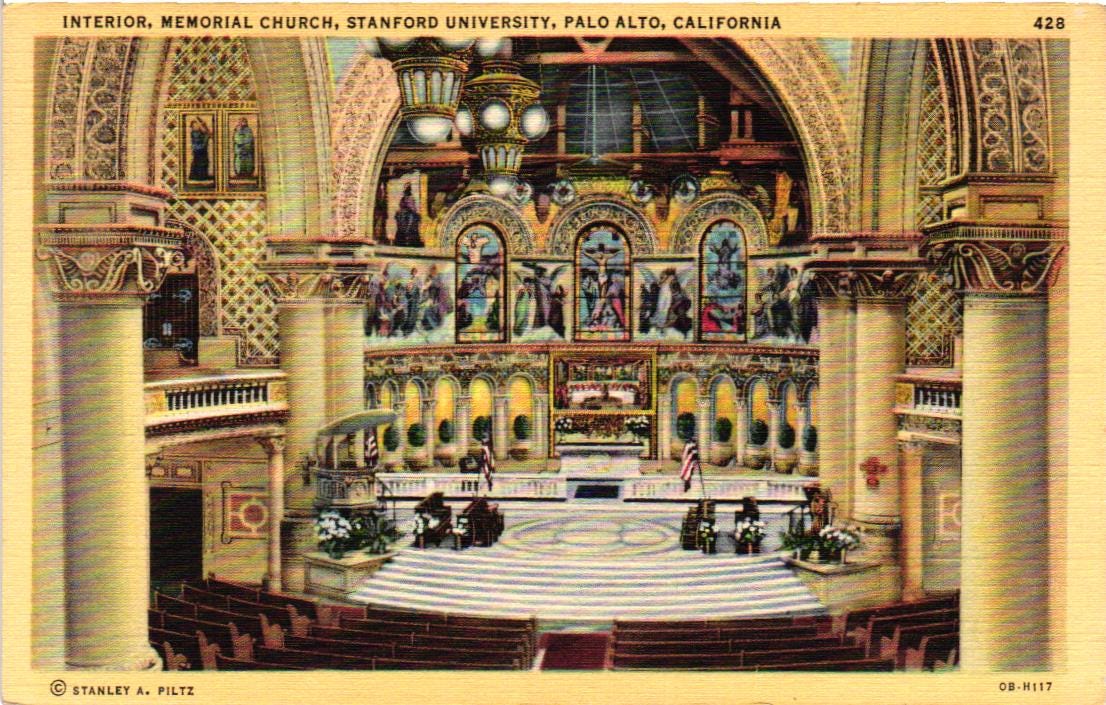

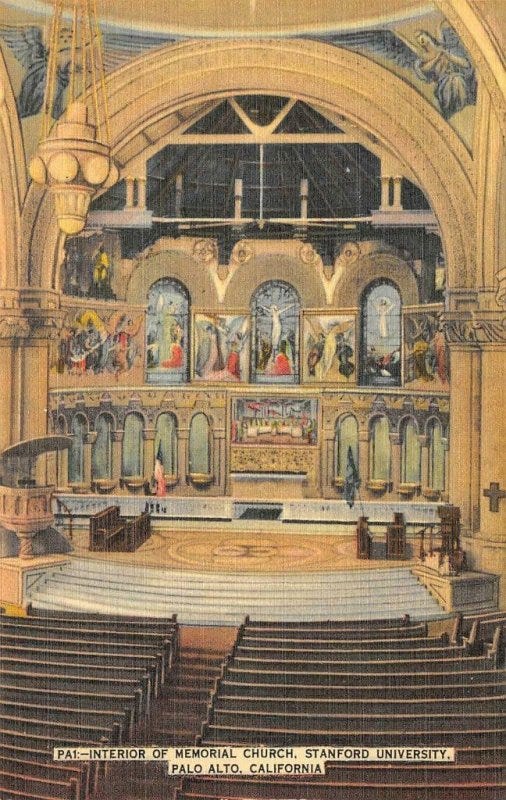

So, this year has found me at my seat in the transept again, staring skyward at the luminous stained-glass. Sometimes I sit for a few minutes to center myself before a day of teaching or caring for cancer patients, but other times—especially if I carry a burden or a problem needing deep thinking—I pass thirty minutes, sixty, even a few hours at a stretch.

It has become my ecumenical celestial room.

Sitting for many hours over the last few months in the church’s cavernous quiet, I’ve been struck that in the midst of a bustling campus filled with students, staff, faculty, and employees of all types and ages and backgrounds, almost no one comes there.

You might easily attribute this to the secularization of academia, and I’m sure there is something to that. But Memorial Church stands out as a decidedly, even determinedly, welcoming and non-sectarian space for any who wish to spend time there. There are few religious services, anyway, so irreligion seems like an incomplete explanation for people staying away—a beautiful church, after all, still offers beauty that can appeal to all comers.

What, then, keeps people out?

Other parts of campus are hives of activity: people throng the bookstore, file through the commons, and stream through the outside walkways like blood cells beating through arteries—and yet MemChu remains almost entirely empty.

From my perch I watch the few who enter. They seem busy about a task—invested, it seems from afar, in becoming briefly acquainted with the church, or seeing the stained glass, or checking this stop off the tour list before they scurry away.

But that very attitude tells me something vital about what keeps people away from Memorial Church and, I would argue, the sacred life writ large: nothing.

Perhaps the reason most people don’t visit MemChu is precisely this: there is nothing happening there. Most of the time, the space is little more than a luminous, silent, stone cavern. Yes, the light filtering through those gargantuan windows bathes the stone inside in crimson, lilac, azure, and yellow—but nothing is happening.

And heaven knows, nothing so offends the modern ethos as nothing.

Consider, for a moment, the advent of the smartphone and the onslaught of social media. What is a smartphone, after all, if not the perfect device for preventing nothing from ever happening to anyone, anywhere, ever again? When I am in line at the pharmacy, after all, I can check in on stock quotes, sports scores, emails, texts, The New York Times—not to mention an endless scroll of social media.

And, of course, the impetus behind a great deal of this online engagement is not information or education, or even just staying in the know. No, what drives so much of our web engagement is dopamine—the neurotransmitter that buzzes our brain when we get a like, or a retweet, or a flattering comment, or even the chance to be righteously indignant. Dopamine squirts make us feel vaguely important, even desired.

We love the internet because it gives the appearance of loving us back. Sometimes, of course, the internet can be a conduit for genuine connection. So much of what happens there, however, takes the outer form of connection and even affection, but without any of the substance that nourishes the soul.

These trends have worried me for many years, but that worry deepened and solidified during a fascinating conversation with Dr. Anna Lembke for an episode of my podcast, The Doctor’s Art. Dr. Lembke, a professor of psychiatry at Stanford University School of Medicine and chief of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic, is one of the world’s foremost experts on addiction and a leading voice on the opioid epidemic. During our podcast, she explained that the ready availability of dopaminergic forces in modern life—whether opiates or pornography or likes or retweets or calorie dense foods—has made addiction nearly ubiquitous.

We surf the web for the same reason we devour a bag of potato chips for the same reason we binge Netflix for the same reason we seek out pornography compulsively—because it feels good, and we never want to stop feeling good. And seeing this as a problem is not just the province of prudes and luddites. Neurobiology provides ample evidence that modernity can sicken our hearts and minds. Even the Surgeon General has now officially recognized the poison that social media is to the developing teenage brain. It is not for nothing that many outlets and authors now suggest that social media could be the “big tobacco” of the early twenty-first century.

Modern life has poisoned our neurophysiology because, as with any addiction, the more we use, the more we need to get a fix. We become so used to “feeling good” that we arrive at a point where we no longer know how not to. Any time spent not “feeling good” seems somehow wrong or wasted. I sit for a moment in silence, and my hand is already twitching toward the pocket where I keep my phone.

So, what are we to do?

My interview with Dr. Lembke returned again and again to this idea: we must reteach ourselves that we are not meant only to feel good all the time. We are, instead, to pass through times of suffering, and we must learn to sit with sorrow without dismissing it or glossing over its depth and difficulty.

As Lehi taught his son Jacob: “It must needs be that there is an opposition in all things.” And this is apparently not just because achieving a state without opposition would be impossible, but because achieving it, paradoxically, would not make us happy.

Our newfound ability to temporarily avoid sorrow at any time and any place has not ushered in a Nirvana without sorrow any more than social media has led us to a world that is universally more connected. Instead, our very attempts to outrun sorrow have brought us to a world drowning in muted, ignored grief. Awash in pleasure, we experience little joy. Adrift in comfort, we find no meaning. Our endless attempts to buzz our brains do not leave us happier. Instead, they increase the amount of dopamine we need for the next fix, and leave us endlessly exhausting ourselves in the search for more. Dr. Lembke even suggests that a recent near ubiquitous rise in anxiety, depression, and other forms of mental illness stems largely from our unending attempts to evade sorrow and the genuine difficulty of life.

Perhaps the antidote to this endless drive for dopamine is, in fact, nothing—the kind of nothing I experience in Memorial Church. For this reason, I have tried to make it my own rule that, when entering Memorial Church, I leave my phone in my pocket, or, if I am in true need of escape, I turn the phone off entirely. I do this because only then can Memorial Church offer respite from a world that otherwise never ceases to intrude.

Nothingness is what prepares us to enter what Dr. Lembke calls “The Great Quiet.” And it is only as I sit within that Great Quiet at Memorial Church that the full weight of light, stillness, and beauty available there settles into me.

This is not to say that remaining in the Great Quiet is easy. In embracing nothingness, I sometimes pass through the travails of withdrawal—the longing, the craving, the tremulous desire. But as I push through these difficulties I find myself newly alive, with senses heightened—eyes, ears, and hearts open as never before.

There, in that world beyond dopamine, I can appreciate for the first time the depth of beauty, the truth of sadness, the power of community, and the reality of love.

That is why I sit in Memorial Church on a Monday morning. Because the quivering silence and kaleidoscopic light highlight that nothing is happening—and nothing is what I desperately need.

Tyler Johnson is a Wayfare contributing editor and an oncologist and Clinical Assistant Professor at Stanford University.

I’ve thought a lot about how Jesus had to get away as often as He could for His own “Great Quiet”, which was often interrupted by 5,000 hungry people or other pressing needs. Oh how He must have cherished precious nothing to prepare for the Everything that was to come.

Thanks much, Tyler, for this thoughtful post! Such a fine antidote for our current moment and addictions.