Sometimes, for our own amusement, or possibly to feel like we are doing something to think about the unthinkable, my family and I imagine what we would do in the event of a catastrophe. How could we manage if the streets of our city—New York City—became unnavigable? Would we inflate our inflatable kayak, tie it to our inflatable air mattress, and paddle down the East River to the harbor and on to . . . somewhere safe? What if we needed to get out and all trains and roads were packed with other evacuees? Could we ride our bikes out of the city and halfway across the country to land with family? How could we live if we were hemmed in with few supplies? Would we be prepared to lie down together and die?

It is a morbid exercise, and yet it is never too far from our minds. Not only do world events in Ukraine, Israel, Gaza, and elsewhere have us imagining our own homes under attack or under siege, but my long-widowed mother-in-law constantly insists and encourages us to prepare prepare prepare. For her, that means she needs a basement full of food and supplies standing ready and waiting for the next big catastrophe. And despite our rather different circumstances—with us already packing eight people into a nine-hundred-square-foot apartment—she urges us to think creatively about how we could use our home as a storage unit as well as a living space.

She has told me she would never turn anyone away who came to her door looking for food. And suddenly to my mind spring the images of dystopian, post-apocalyptic fiction that I’ve seen on TV or read in novels: people scrounging for food, shooting anyone who has some, scraping by and stooping to unspeakable acts to secure their next meal. I wonder if I really want to participate in that kind of a world.

And yet, the grim task of thinking about the unthinkable—of nuclear winter, of attacks on major urban centers, of advanced climate-change disasters—seems an important mental drill, not only for our family, but for at least a substantial subset of society who make emergency preparedness and survivalism serious hobbies, or the subject of various forms of art. It is a way of playing that helps us approach those extreme possibilities and to suss out what we might need—or want—to do to survive. Perhaps this practice brings us to the realization that, ultimately, we are not in control and we must develop faith in the unknown.

But planning is something we all must do. Preparing is a way to ensure that when things go south, we will be able to rise above the fray, unafraid. We often use past experiences to help identify places in our lives that need to be shored up and protected.

When I see my mother-in-law’s basement, I recognize that as a young widow, she no doubt relied heavily on her storeroom during the years when her children were young and she was not yet able to work full time. My grandmother also had a basement room with shelves stacked with canned goods. My cousins and I would make a game of finding the oldest or most bizarre food product in the place—fully cooked canned bacon from the ’60s—and wonder why she didn’t just throw it out. In retrospect, as a child growing up in America during the Great Depression and as a young woman during WWII, Grandma had her own memories of hunger, want, and deprivation to guard against.

I see the efforts of these strong and careful women, and I understand and applaud the wisdom of setting aside and storing up both food and money for the very real possibilities of unemployment, debilitating illness, and unexpected death. And yet, today it strikes me as both too much and not enough at the same time.

I see a mismatch in the “emergencies” of our times and the ways we have been taught to “prepare” for the unexpected. While very prudent and practical, our industrial shelving units stacked with #10 cans of dehydrated potato pearls will only get us so far in a time when loneliness, addiction, anxiety, and helplessness are emerging as the urgent issues affecting our health, our communities, and our lives.

I’m not alone in seeing a mismatch. Leaders of the Church have included sections on developing emotional resilience in the latest emergency preparedness publications. They’ve shifted focus from building up stores of food to helping members build greater self-reliance.

But it’s not just that the “emergencies” and the “preparation” don’t match, it’s that focusing on the storage preparation plan can blind us to other devastating and destructive problems. When we are so focused on guarding against hunger or maintaining the maximum level of self-sufficiency, we can miss the ways in which that focus undermines our sense of community and builds a sense of false security. Beyond that, focusing on our physical preparedness that we “shall not fear” is at odds with another important bit of counsel to “take therefore no thought for tomorrow” and instead have faith we will be able to meet life’s challenges as they arise.

So, what is it that we fear? What do we need to be prepared to combat or avoid? Hunger, illness, death? But we all have hungers, physical and otherwise, that may never be filled. We all experience illness and disease of many kinds. We all will die—some of us proverbially multiple times in multiple ways before our bodies are permanently laid to rest. And so it seems that perhaps, in addition to doing what we can to strengthen our ability to confront these physical weaknesses, we also need to live in a way that when they do become part of our experience, it is not an experience coupled with and intensified by fear.

In my mind, the counsel to be prepared must be about living in such a way that when we find ourselves in any situation, we feel that it is exactly what we have been living for, that this is just where we want to be. Like the little jar of “prepared horseradish” I keep in my fridge and sometimes mix into the filling for a supper pie or smear on a baked potato, where it adds contrast and life to the most basic of meals. The flavor and the heat also recall the many trips my family took to Arby’s when I was a child, where the salty meat sandwiches were tamed and elevated by the addition of a squeeze of creamy Horsey Sauce from little plastic packets. The sauce stands by, waiting for its moment, and boldly steps in to enliven any meal. It was prepared for just such a thing.

In the Book of Mormon, the missionary Alma begins to look for those who need to hear the word of God. He searches in synagogues and preaches on the streets, finding that those who are most receptive are those who are “in a preparation to hear the word.” That is, they have been humbled by their trials, by their poverty, by the lack of dignity they have been given. They are ready to be changed from these raw, coarse, discarded people to become just the right thing that would bless, elevate, and deepen any situation they may find themselves in. They are ready to look to God, and in doing so, to truly live. Having nothing, they are ready for anything.

This is what I think of when I think, deeply and honestly, about the unknowable, unimaginable curves life can take. I think that when God said, “If ye are prepared, ye shall not fear,” He was speaking less about seventy-two-hour kits and three-month supplies and more about being, as these people Alma found to teach, “in a preparation” to do or accept whatever it is the situation calls for at the moment. That is, to be humble, grounded, flexible, and open. To live our lives in such a way that when we are faced with difficulty, destruction, and even despair, we will be able to discern the best course of action step by step, led by faith.

One such example from literature is a story my elementary school librarian read to my class when I was around ten years old. Week by week, chapter by chapter, Ms. Chadwick told us the story of Mama’s Bank Account by Kathryn Forbes, and the trials and travails of a Norwegian immigrant family trying to make their way in San Francisco in the 1920s. While the family was poor, they always had the comfort of knowing Mama had a bank account to draw upon if necessary. The family went to great lengths to protect that bank account so they would never lose the security it offered. But of course, when the children were grown and the family was more established, Mama revealed that she had never even been inside a bank. She had helped them through various struggles, disappointments, and missteps with a resourcefulness and faithfulness that led, in a roundabout way, to better educational opportunities, resistance to peer pressure, and a strong family culture that protected them all from the pitfalls of a life unmoored from their homeland.

Mama’s family was not fearful about their survival; they were hoping to thrive in their new country, to live well. Living not merely by avoiding death, of course, but by finding joy and peace amid the chaos and confusion of daily life. Mama was well prepared, but not because she had money stored away. Her preparedness lay in her strong imagination, good will, and clear vision.

Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl famously advocated for finding the strength within ourselves to make any situation—apocalyptic or mundane—a situation in which we can bring whatever is needed. “It [does] not really matter what we [expect] from life, but what life [expects] from us,” Frankl wrote. We must “think of ourselves as being questioned by life—daily and hourly.” I wonder how we prepare our answers.

How do we answer when life asks us about the “emergencies” of our day—things like anger, or loneliness, or depression? Are we prepared to reach out for help when we need it? To humbly admit when we don’t have the answers? To seek out those who need the light that we carry or the rest we can provide?

It is tempting to think of our physical preparations as protection. If we didn’t have a basement full of supplies, plus go-bags for every member of the family, we would surely regret it. It would be tempting fate to make fools of us. Our goods are a line of defense—but a thin and incomplete one, porous and faint. It can give us the illusion of security when in reality, it could all be taken away or rendered useless in many scenarios. It can give us the illusion of self-sufficiency and prevent us from developing the community, cooperation, and interdependence that we need most in trying times. It can weigh us down, holding us fast when what we need is freedom to move.

Can we instead develop societies that are practiced in supporting each other through the daily wear and tear of living in the world? If we can do that, we can be truly prepared for anything. We can bring peace to ourselves, our communities, our world. We can share meals with the families managing the postpartum transitions and intense cancer treatment schedules, and we can also share more moments sitting on the porch listening to children playing, watching for signs of stress, and shouldering the burdens of everyday life and earthly relationships together. Developing those connections creates a network of strength so that the inevitable internal, individual trials are not catastrophic.

Among our “emergency preparedness” supplies should be an ample amount of resilience and acceptance. We should have, in our stockpile, a practice of working through difficult emotions and finding tools to help us calm our fears so that we can think clearly to find the next right step. Our cache should include a web of strong relationships we have developed and nurtured in ways as small as a smile and nod as we pass on the street and as large as being on the front lines of support for a family facing a difficult or deadly diagnosis.

When I imagine preparing for those other scenarios, instead of inflating air mattresses and bicycle tires, I see us looking out of our windows, searching for those who may need our help. With less than nine hundred square feet to work with in our own home, I see us reaching out of our comfort and into the unknown, taking hold of it and learning about it until our discomfort abates. I scan our friends, family, neighbors, and acquaintances and recognize the gifts and strengths in each one that I could call on when my day has had a hiccup or my life has been derailed. I notice a new mom, sleep deprived and overwhelmed, and I know I can bring her a listening ear, an hour or two of rest, and the comfort of a couple of healthy meals. I recognize that I am in a preparation hoping to add whatever is needed, wherever I happen to be.

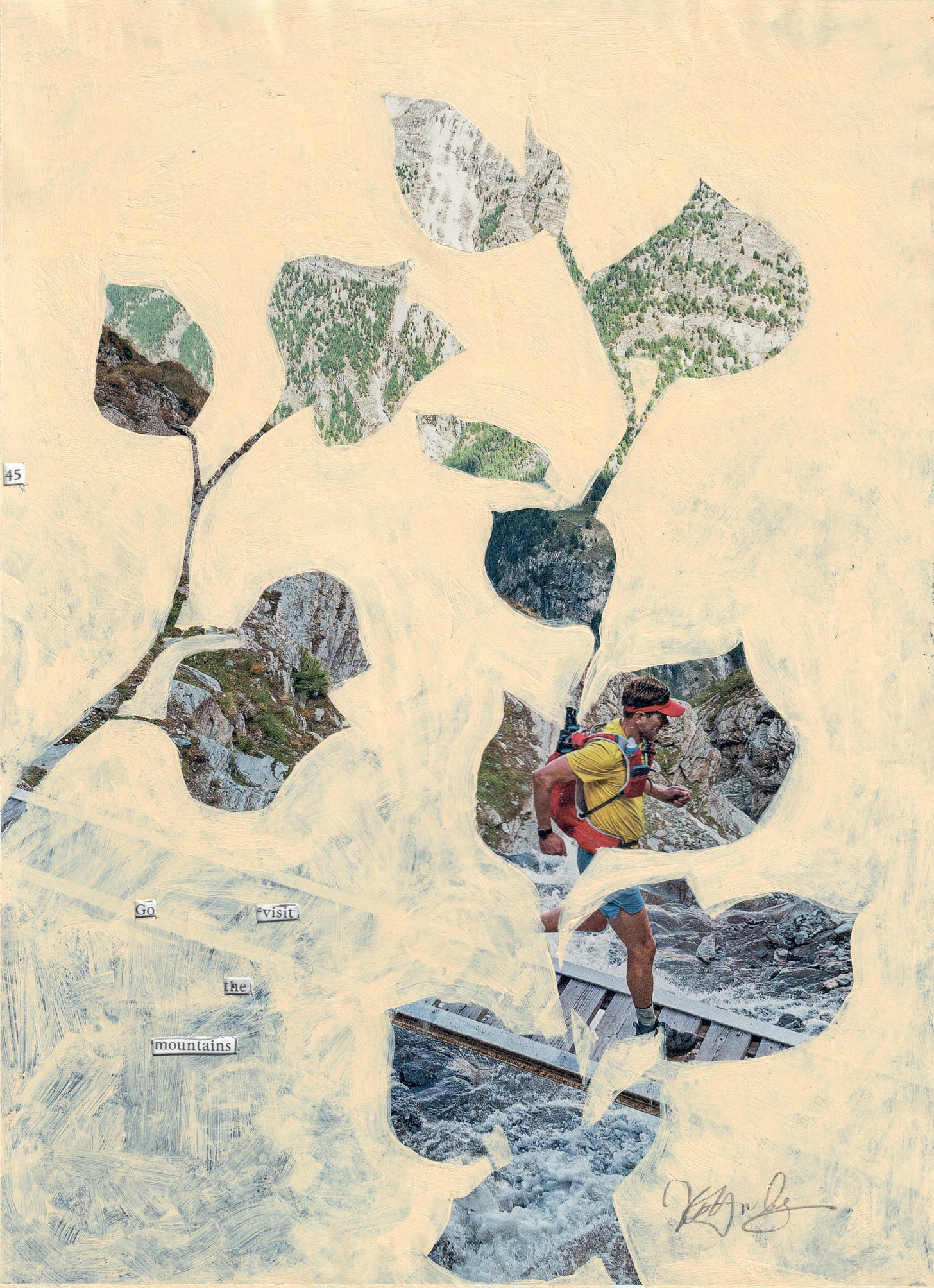

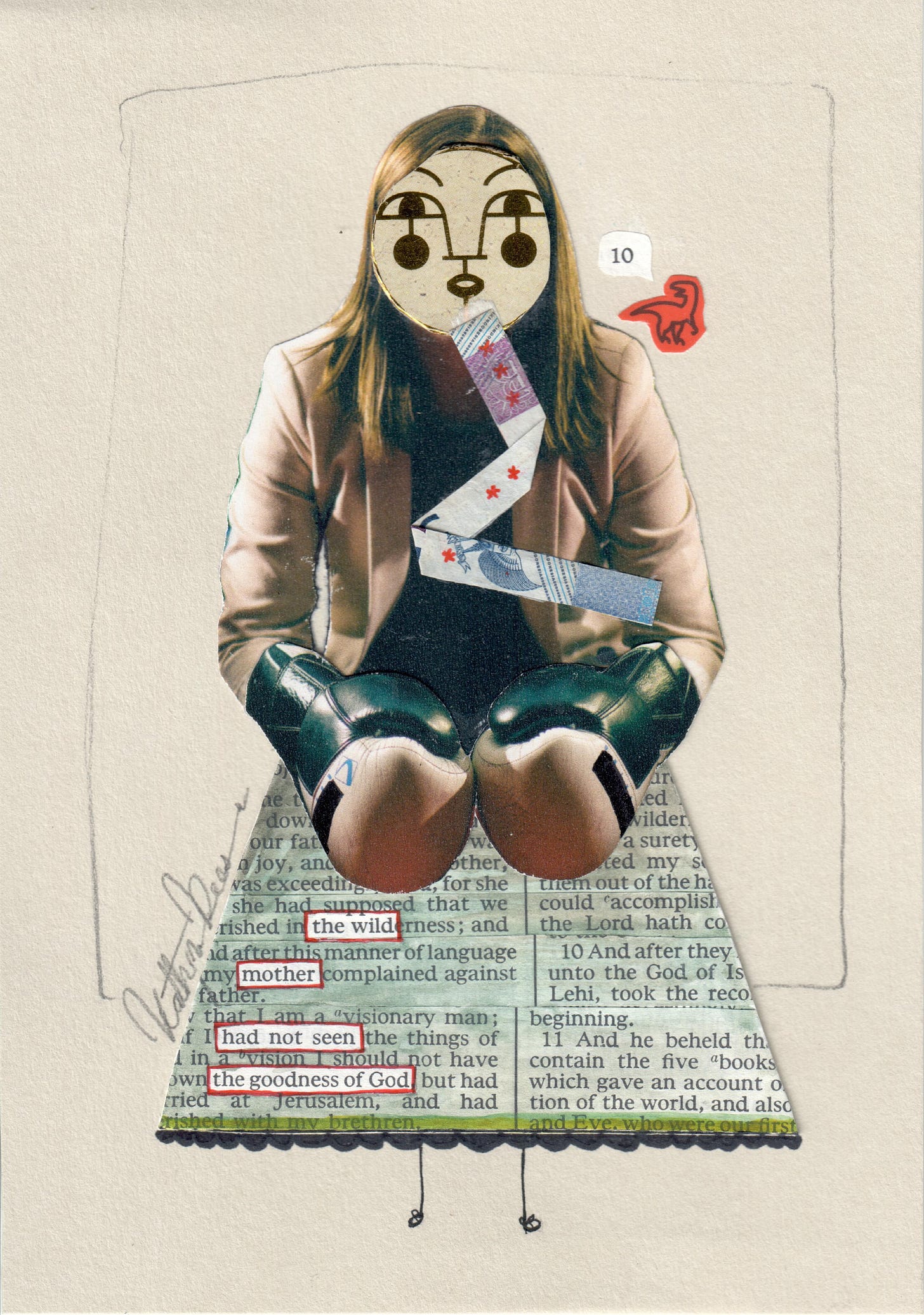

Lizzie Heiselt is a reader, writer, runner, and mother living in Brooklyn, New York. She studied American Studies at BYU and Journalism at NYU.

Kathryn Reese is a mixed media artist based in Utah.