When the world seems to be falling apart around me, I think of Svetlana Boym.

Boym was a professor of literature, an artist, and a perceptive cultural critic. Born in Leningrad in 1959 to a family already disillusioned with the official national dream of a workers’ paradise, she fled the Soviet Union at age nineteen. At the time, she thought she might never see her parents or childhood home again. But in the United States, she outlived the terms of her exile: in 1991, the Soviet system collapsed.

That same year, the Sistine Chapel reopened after a decade-long closure to care for Michelangelo’s ceiling frescoes. Rather than merely working to head off decay, the Vatican had authorized a team of specialists to remove layers of ash and grime. Using a computer-aided technique to strip away intervening layers, the conservation team promised to bring back the brightness of the original colors. But not everyone was happy. A few art historians argued that the removals were going too far, erasing some of Michelangelo’s own charcoal outlining and shadows. In the end, the cleaning wiped the pupils off a few figures’ eyes.

On a trip back to Europe, Boym saw the finished product. Looking up at the ceiling, she missed the once-prominent crack in the paint between God and Adam. Beyond questions of whether the project had gotten Michelangelo’s intentions right, she worried that the attempt to remake the frescoes as they had been was getting in the way of the masterpiece they had become. For her, a great artwork is much more than a good painting. Great art gathers associations over time; their history is part of their power. What computer models coded as ash and grime, Boym saw as traces from generations’ worth of candles and incense. For her, the brightened color mattered less than a discarded aura of history.

How exactly are we expecting to be transported through time when we visit a historical place or work of art? As she considered the Sistine Chapel ceiling and other examples, Boym categorized approaches into two broad types. In The Future of Nostalgia, she uses the term restorative nostalgia to describe efforts to remake the present in the image of a real or imagined past. To do so, she noted, restorative projects have to settle on a pristine moment to be restored, as if setting the dial on a time machine—like the Sistine Chapel team choosing to transport viewers back to the moment the paint on the ceiling dried (even if that was before the pupils were drawn on). A disappointing present could be replaced, and erased, by that specific, desired layer of the past. Boym contrasted this with an approach she called reflective nostalgia. Reflective nostalgia, she wrote, was less about the return home than the longing for it. It involved a relationship with the past that embraced the cracks and decay, in which a viewer’s goal was not to reach a given past but to reflect on time’s passage. For Boym, the great virtue of the reflective mode was the flexibility it offered, allowing viewers to examine time without becoming locked into any given layer.

For Boym, these questions about nostalgia were not only about how we handle aging works of art. Looking at eastern Europe in the 1990s, she also wanted to know how societies would relate to their pasts. Some chose reflective routes. In Prague, for example, Boym visited a giant statue of a metronome, which had been commissioned to fill the empty pedestal of an old communist monument. But not everyone felt so playful. By the mid-1990s, as high expectations for the post-Soviet era gave way to upheaval and uncertainty, Old Songs About the Most Important Things made its way up Russian CD sales charts, and millions tuned into a TV show called The Old Apartment. Boym worried that the growing marketing power of the word old revealed a longing for “the good old days, when everyone was young, some time before the big change.” Though she knew that the good old days are usually a mirage, she also recognized that imagined pasts can have real consequences. If leaders decided to restore a lost Russia, what would they first have to try to wipe away?

In 2014, Boym was diagnosed with cancer. That same year, Russian troops slipped into Crimea and eastern Ukraine. She died the next year, having already foreseen how the way we approach an old painting might relate to the ways we wage war. Countries make poor canvases. Now I scroll through news about young men, often drafted against their will, who fight over the meaning of the past with tanks, drones, and artillery on muddy battlefields reminiscent of World War I. A thousand miles further south, Israelis and Palestinians are caught between the mutually exclusive visions of Hamas, which is determined to restore Muslim sovereignty from the River Jordan to the Mediterranean Sea, and figures like Bezalel Smotrich, whose ambitions to expand Israeli territory are driven by ideas about the past rather than realistic assessments of the present.

Elsewhere, too, people have been caught by the claims of imagined pasts. As voters find the present lacking, I read about a worldwide wave of nationalist political parties who promise that they alone can vanquish pain and turn back time. In my neighborhood, I walk past flags that say Make America Great Again. With some vital bonding agent losing strength, the world seems to be falling apart around me.

And I think of Svetlana Boym.

I live in a global twenty-first century. But I live as a Latter-day Saint.

How do we relate to our past? It’s hard to say. In Nauvoo, sites take a restorative approach. Instead of a monument to the scattered stones of the temple, I can visit whole blocks set to mimic the city at its height. The houses are furnished; the patterns in the wallpaper are uniformly taken from the early 1840s; the blacksmith shop is open for business. At the Daughters of Utah Pioneers Museum in Salt Lake, I get a very different experience—one more consistent with Boym’s descriptions of reflective nostalgia. Somewhere between the case filled with bits of pioneer barbed wire and the turn-of-the-century fire truck tucked into the basement, there’s a graying piece of sacrament bread saved from the Salt Lake Temple’s dedication. Rather than transporting me to the past, these exhibits remind me that I’m standing in the present, looking from a distance over a lost world of fruit dolls and hair wreaths. In other places, utilitarian concerns prevail over either mode of nostalgia. In our recent reconstruction of the Salt Lake Temple, for example, we just tore out the original murals and tucked the pieces away.

But the past doesn’t always stay in storage. The past few decades have had their own upheavals and uncertainties for Latter-day Saints. In the late twentieth century, Church growth and a family-centered culture were important pillars of our collective identity. Prominent statistical differences in the early twenty-first century include lower conversion rates, activity rates, marriage rates, and birth rates. Accompanying these measurable differences is a general sense of weight, an intuition that the Church is somehow carrying more baggage than it once did. In an early Wayfare piece, Joseph Spencer observed that it’s become far more complicated to live in American society as a Latter-day Saint since the end of the 1990s. He mentions changes like “increased political divisiveness, the internet-enabled expansion of information, new forms of identity politics, the rise of social media, and the impact of a global pandemic,” as well as a shrinking sense that there’s much outside the economic and social systems we now spend our time debating.

Whatever larger social forces and internal dynamics are at work, it’s easy to see how a Latter-day Saint today might long for a different time. A missionary in a secularizing society might read wistfully about mass conversions in nineteenth-century England. A Primary president might wish for a time when the average member spent more attention on the ward, and it was less of a challenge to fill callings. A person who walks on eggshells with a loved one over differences in faith might wish for an alternate reality where the shared rhythms of religious life can still be taken for granted. We may be looking back with rose-colored glasses, but of course we look back.

And when we look back, we often want to put things back the way we think they were. This impulse toward a restorative nostalgia for our recent history can take many forms. I often hear people speak wistfully, for example, about an idealized pre-Correlation past, a time when the Church was less institutional and impersonal. Like the Sistine Chapel ceiling’s aggressive conservators, some dream of wiping away the layers of bureaucracy that accumulate with age to bring back a lost communal vibrance. Unfortunately, an overzealous opposition to bureaucracy can make it hard to acknowledge the humanity of individual bureaucrats (and in the Church, many of us end up enlisted in that category at one time or another). Rather than seeing an organization president, a bishop, or a prophet as a rounded human wrestling with genuine complexity, a lens of restorative nostalgia can make them look like obstacles, then enemies. It turns out to be shockingly easy to demonize others while speaking for unrestrained fellowship and love.

Other Saints really miss manuals from thirty years ago. People in this group long for days just before the internet, when Church publications could offer simpler, more streamlined shared narratives. In search of a time before they were expected to think about Joseph Smith’s use of seer stones or wrestle with his introduction of plural marriage, a growing minority are now embracing conspiracy theories about the Church’s early history—such as that Joseph never introduced polygamy, or that Brigham Young orchestrated Joseph Smith’s assassination. Friends of mine who study Nauvoo history have been baffled by these theories’ remarkable persistence in the face of strong historical evidence. But not all problems with history can be solved by the methods of professional historians. How persuasive can we expect 1840s documents to be if someone’s real problem is that they don’t like the 2000s?

Still other Saints seem to yearn, on some level, for the apparent moral clarity of the Cold War years, when their political and religious convictions could be merged into a shared critique of one clear enemy. In some quarters, patriotism and devotion are urgently searching for an enemy to rally against. The irony is that these Saints’ and patriots’ thirst for comforting extremes often leads to conflict with the moderate forces in Church and government. In the most acute cases, the longing for a past defined by national and religious loyalty turns people aggressively against nation and religion. (How many anti-government words have been uttered under the banner of the US flag? How many heresies, holding a Bible?)

The hope for some kind of connection with the past is deeply human. It may well run as deep as hunger or sexual desire. But hunger and desire can easily damage individuals and relationships if they are not channeled in an effective way. It matters a great deal how we think about what we want.

I sympathize with Saints who feel unmoored. I, too, feel the terror of these currents we are passing through. The siren song of return to a safer past calls out to us—but if we listen too long to that melody, the story always seems to end with someone dashed against the rocks.

Just over a decade ago, when I first encountered Svetlana Boym’s work, I didn’t respond so viscerally to her warnings about nostalgia’s dangers. Instead, her work piqued my intellectual curiosity. I was struck by the fact that her category of restorative nostalgia shared a key term with my belief in a restored gospel. Was that only a coincidence? Or was Latter-day Saint use of the term restore a sign of the nostalgia built into our religious view of time?

Boym’s work pushed me to more deeply consider Joseph Smith’s work. I thought about his aesthetics, about the particular kind of temporal logic that guided him. Clearly, he was a prophet preoccupied with the past. But what did Joseph Smith want from it?

To understand the flavors of Joseph Smith’s nostalgia for the religious past, it may be helpful to begin with a point of comparison. Many other Christian leaders have been interested in the lost practices of Jesus’s earliest followers. Alexander Campbell, a Christian primitivist preacher and publisher active in nineteenth-century Ohio who was a mentor to Sidney Rigdon, offers a fairly direct point of reference for considering Joseph Smith’s work.

Deeply influenced by Enlightenment thinkers, Campbell believed in using common-sense rationalism to strip away historical accretions until he and his followers reached bedrock Biblical truths. From that assumption, he reasoned that all the world’s Christian denominations could easily be united into one body if they would only return to a past moment of consensus before any splintering took place.

In search of that moment, Campbell was selective about which parts of scripture he considered authoritative. In his writings, he dismissed the Old Testament as an artifact of fulfilled Mosaic law with no relevance to Christians’ salvation. He likewise cordoned off the miracles in the New Testament, framing them as signs to confirm the truth of the gospel, supplanted after the time of the apostles by the recorded witness of scripture itself. To reclaim the Bible, Campbell was quite willing to flatten it. Boym’s ideas about restorative nostalgia can help us explain these boundaries to Campbell’s biblical consciousness. Like other restorative projects, Campbell’s quest was necessarily aimed at a specific and static moment in time. In his case, the moment of lost Christian unity could be reclaimed exactly at the seam where the Bible ends and subsequent history begins.

Alexander Campbell and Joseph Smith agreed on many points. Both rejected infant baptism, advocated an organizational structure inspired by the New Testament church, and prioritized principles like faith, repentance, and baptism. But their approaches to the past could hardly be more different.

While Campbell attempted to recover a pristine past through biblical analysis, Joseph Smith was publishing the Book of Mormon as an ancient American volume of scripture, describing multiple interactions with angels, and calling for the scattered house of Israel to gather in Ohio and Missouri. Rather than attempting to recover an obscured past by trimming the present down to its image, Joseph Smith was interested in expanding the present by feasting on an eclectic mix of genuinely lost pasts. Instead of singling out a static moment to restore, Joseph channeled multiple moments through mystical interaction or embodied, collective reenactment. The restored gospel arrived, in other words, as an ongoing recasting of many dynamic moments in covenant history.

This is deeply strange stuff. If Alexander Campbell’s approach was like scraping unwanted layers off the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Joseph Smith’s was more like restoring the chapel ceiling by painting a wild new work in the same spirit across the chapel floor.

One striking feature of Joseph Smith’s mode of bridging past and present is its radical embrace of simultaneity. The revelations he received draw liberally on Old and New Testaments, mixing the images of the house of Israel and the primitive Church. He was energized by thoughts of ancient Americans and ancient Egyptians. In the revelations and his teachings, Independence, Missouri, is many things. It is the site for a New Jerusalem, intended to coexist with rather than supplant the old holy city. It is a promised land on the border of Gentile and Lamanite, an intersection full of forgotten pasts and promises. It is an echo and twin of Enoch’s Zion, a copy which will someday meet and merge with the original in a moment of mutual culmination. It is the Garden of Eden—the beginning of the world—at the same time it is a site where Christ will come suddenly to his temple at the world’s end.

To lay the cornerstone for a temple half a world away from the ruins of the still-revered Jerusalem original hardly feels like Boym’s restorative nostalgia, where one past conquers another. But to literally lay a cornerstone for a temple at all feels different than Boym’s category of reflective nostalgia, which calls attention to the passage of time and the inevitability of loss.

In Missouri, arguably, the early community of Saints ran up against waves of hostile local restorative nostalgia. Branded as a threat to the Way It Used To Be, they were driven from their homes. For helping us understand the Saints’ emerging approach to nostalgia, the expulsion from the original site of Zion is instructive. What role would Independence, Missouri, play in the Latter-day Saint imagination after it was lost?

The dream of return, and concrete efforts to restore the Saints to their promised lands, are an important theme in the early 1830s. But alongside those efforts, a fascinating development unfolds. Within a few years of expulsion from their Eden in Independence, revelations to Joseph Smith designate some of the unwanted upper Missouri lands they had come to occupy as Adam-ondi-Ahman, the place where Adam and Eve built an altar after leaving the Garden. In an alchemy of longing, the place of exile becomes a sacred space.

Roughly the same happens in Nauvoo, which is named for the particular saving beauty referenced in Isaiah 52:7. And then again with places like Mount Pisgah on the pioneer trail, or in Utah with its salt sea, Jordan River, and Zion in the mountain tops. Latter-day Saints can still weep for their promised land in Missouri, but there is no need to fight for it. Someday, the Lord will fight their battles. In the meantime, the sense of promise seems to follow them, flow through them, wherever they go.

What could we call this mode of nostalgia? Both Boym’s categories begin from an assumption of an unmoored present looking toward the past for either a fixed anchor or an orienting landmark. But for Joseph Smith, the past can also move. Under the right supplications, the past responds and engages in open conversation with the present. In personal and shared supernatural experiences, Joseph and others conversed with angels—who they understood not as separate heavenly beings, but as resurrected figures from human history who could bring old tools to the work of a new epoch. In Doctrine and Covenants 130, Joseph Smith taught that angels access past, present, and future, which exist continually before the Lord. In contexts like the temple endowment, Saints could likewise bridge time, bringing ancestors’ time and sacred history into conversation with the present.

I call this mode of engagement mystical recall. Recall because it involves bridging the distance between past and present by summoning the past. Mystical in reference to the Greek term mystes—meaning an initiate who received knowledge through a sacred drama—because the past has to be met, has to be given room to listen and act, for such summoning to work.

The technique is not unique to ancient mystery rites or to Mormonism. At a Passover seder table, Jews are slaves in Egypt. This is true every year and in any place. An observer might say that this image is only a metaphor to link the speaker to themes of oppression and deliverance, and that there’s a vital distinction between the real table and symbolic Egypt. But I don’t read the haggadah text that way any more than a Catholic simply eats a wafer or drinks wine during the Eucharist.

To me, these instances of religious language operate by power of their animating recall. In such moments of sacred drama, time collapses. The past and present become equally real and equally suggestive of a deeper reality. During the Latter-day Saint temple endowment, eras and identities coexist. I am James and my wife is Nicole; I am Adam and she is Eve.

In Latter-day Saint thought, this logic of mystical recall extends beyond ritual. Our worldview is woven out of living pasts, enchanted presents, and promising futures. Consider the concept of Zion. For us, Zion is a Jerusalem hill, but it is not only a Jerusalem hill. When we called it to Independence, it both came and remained in Jerusalem. When we called it to Deseret, it also remained in Independence. We are perpetually building Zion in our wards while also occasionally experiencing Zion in our wards at the same time Zion waits for us in past sites and a future city.

In the face of upheaval, we don’t actually need to turn back the clock. Latter-day Saints’ most successful method for moving on from periods of conflict and loss, of victimization and victimizing, has been to bring the past forward. That power remains in our reach.

Consider the example of the “refugee crisis” of 2015–2016. In that year, events like the Syrian civil war drove millions of people from their homes. In many European countries and the United States, the prospect of rapid population exchange led to a spike in support for aggressive nationalist groups. These groups played to fears about change and promised to put things back the way they used to be. But that’s not at all the language and action that came from the Church.

Under Linda Burton’s direction, the Relief Society called on the Saints to aid refugees. In that effort, Church leaders enlisted our collective memory. President Burton’s April 2016 general conference address invoked Emma Smith’s teachings to the Nauvoo Relief Society and quoted from Lucy Meserve Smith’s accounts of the 1856 handcart rescue. Burton worked to turn her listeners’ hearts, linking the contemporary spike in refugee needs into a genealogy of those extraordinary occasions.

In his address, Elder Patrick Kearon worked to spiritually link Latter-day Saints to refugees through the shared dramas they had enacted. “As a people, we don’t have to look back far in our history to reflect on times when we were refugees,” Elder Kearon said. “Their story is our story.” Far from presenting the past as a safe alternative to the challenges of mass migration, he summoned the past to explicitly call on modern Saints to rise to the challenge. “Let us come out from our safe places and share with them, from our abundance, hope for a brighter future, faith in God and in our fellowman, and love that sees beyond cultural and ideological differences to the glorious truth that we are all children of our Heavenly Father.”

Stirred by the spirit of mystical recall, my desire to live in easier times falls away. If we feel alone in this moment, we can cry out for Moroni. If we are lost in the wilderness, we can make it Adam-ondi-Ahman. We can live in the present and lift where we stand by summoning pasts to sustain us. God, grant us the hour’s challenge. May it help us to reach deep.

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

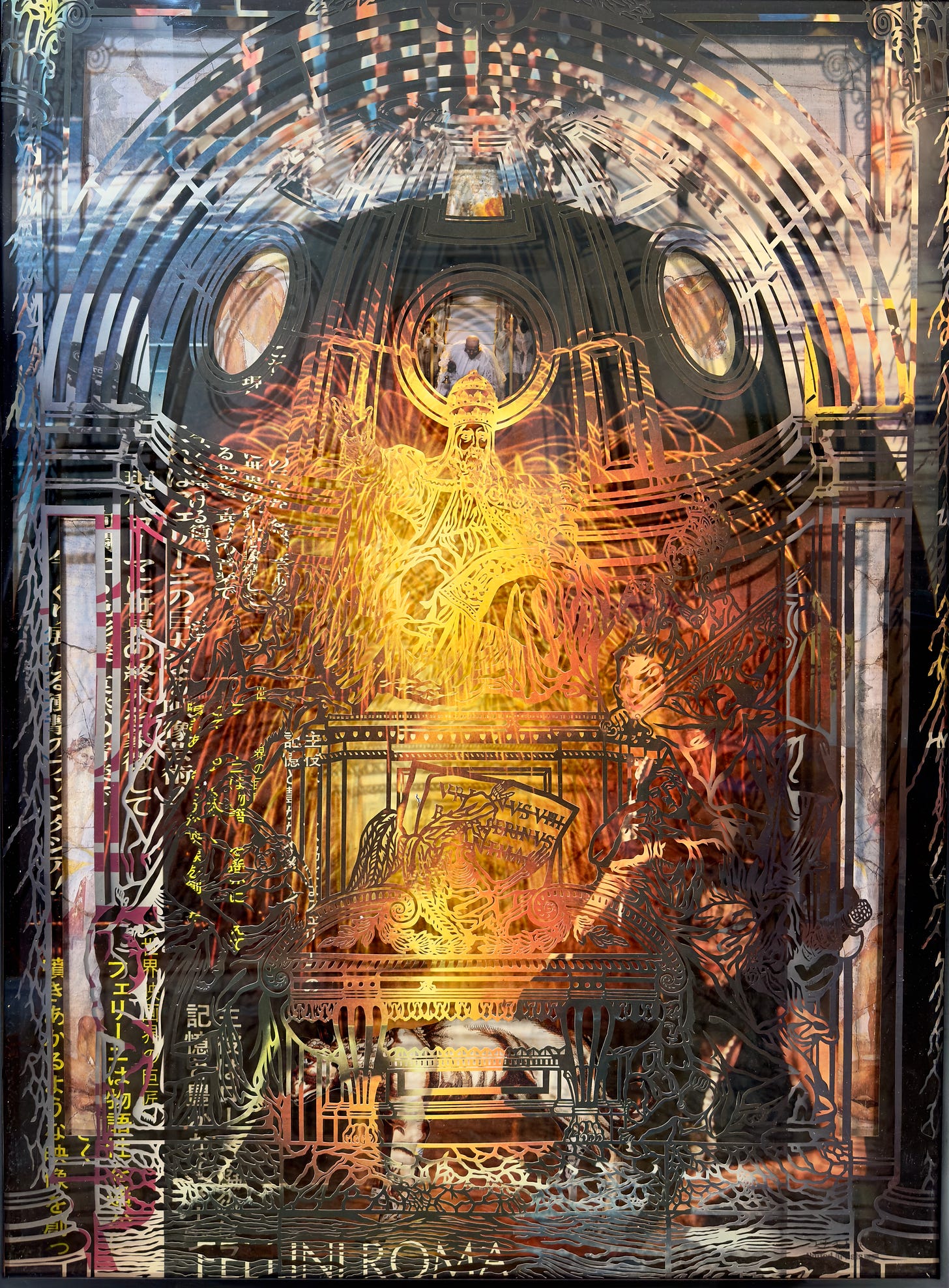

Matthew Picton has been a professional artist since 1998 and has exhibited widely on the West and East coast of the United States and participated in numerous art fairs. He has exhibited internationally in the UK and Germany. His work has been reviewed in many publications world wide.