Please find here our collection of art and writing to inspire you this Easter season. If you would like to receive these Holy Week meditations in your inbox, please subscribe to Wayfare and then manage your subscription under your account and turn on notifications for Holy Days.

“Is it not written, ‘My house shall be called a house of prayer for all the nations’?

But you have made it a den of robbers.” —Mark 11:17, NRSV

MEDITATION

If we are serious about this whole idea of building Zion, we need to make room for everyone, because Zion isn’t Zion without all of us.

—Samuel Benson, “A Zion for All of Us”

How do we become a house of prayer for all nations, not just for people who look like us, walk like us, and talk like us?

ACTIVITY

How to make a perfect boiled egg: Place eggs in a large pot in a single layer. Cover generously with water. Place lid on pot and bring to a boil. Let boil for two minutes. Turn off heat and place 1/8 tsp. baking soda in the water with the eggs. Keep pot on the stove with the lid on for ten minutes. Drain hot water and rinse eggs with cold water.

ESSAY

REDEEMING THE DEAD Peter Mugemancuro

I attended a temple endowment session for the first time as a sullen eighteen-year-old, grudgingly preparing for my mission to Chicago. I have always been very aware of my personal imperfections; the white, soaring walls of the LA temple felt forbidding and even uninviting that day as I walked inside. As I waited for the ceremony to start, I wondered, Should I even be here? I’d spent the last six months trying to figure out how I could leave the Church without kicking up too much fuss, and yet here I was on the verge of making commitments to God that in my mind I’d have no choice but to try and keep for the rest of my life. The cognitive dissonance made me feel punishingly out of place. The unfamiliar wording and symbolism of the endowment session only heightened my impostor syndrome. As I was invited to keep the law of chastity, I was uncomfortably reminded of my bisexuality. My hand went up in grim assent even as I thought, This could get me in serious trouble later. I came to the end of the ceremony confused, a little stunned, and almost entirely uncomprehending. If I was supposed to have seen angels or had visions, I had utterly failed. I felt the Spirit a little, but only around the edges.

I went to the temple again near the end of my mission in Chicago. The missionaries in my cohort had come out six months before the start of the coronavirus pandemic; quite a few of us went home early, and those who remained had served in circumstances that we never would have bargained for. Entering the Chicago temple that day, I felt a profound sense of wholeness. For Latter-day Saints, the temple is where we’re supposed to experience what it’s like to be in God’s presence. I was there with some of my closest friends. We’d served together, laughed together, and suffered together. We probably wouldn’t ever all be in the same place again. This time, the endowment ceremony washed over me in waves of grateful appreciation. Somehow it seemed much more familiar; once-confusing symbols and words held a far richer significance. Entering the celestial room of the temple was everything I’d ever imagined it would or could be; it felt like I was entering the presence of God. When the time came to leave, I didn’t want to go. My soul was abundantly satisfied. I didn’t see angels or have visions, but I felt God loved me to the point where it overwhelmed my senses. The Spirit was so intense that I cannot put it into words.

I don’t share these experiences in this order to suggest some sort of nice, linear pathway from doubt to faith—since I’ve come home from my mission, my temple worship has continued to both inspire and challenge me. I share them because they nicely highlight one of the Church’s unspoken fault lines: the gulf between those who feel comfortable attending the temple and those who do not. Holding a current temple recommend sometimes feels like the Latter-day Saint equivalent of an American Express Gold Card, offering access to all the spiritual (and social) benefits of Church membership. By contrast, not holding one (or not living the Church’s moral standards with sufficient rigor to attend) might feel like a shabby, second-tier alternative, a sort of Mormonism-lite. While I personally choose to hold a current recommend and do my best to live the associated standards, some friends whom I deeply care about have found that they don’t feel comfortable playing word games in ecclesiastical interviews when their genuine love for the Savior and his gospel doesn’t quite stretch to an uncritical embrace of his restored Church. As a Black, queer, and nevertheless fully active member of the Church, I have learned through abundant personal experience that those two feelings are not necessarily the same thing.

This all being said, my personal experience also tells me that attending the temple is much, much more than a sort of spiritual Disneyland fast pass. I find genuine power there, much more so because of the effort required to align my life with the standards for attendance. The temple is the place where I most strongly feel that God cares about the things that matter to me—even if it’s a difficult exam or a passing relationship worry. My worship there is a compelling source of personal light and truth, and I am not ashamed when I say that it’s literally the house of God.

How can both of these things be true? How can the temple simultaneously be a place of stinging alienation and ineffable spiritual uplift? More to the point, how might we as disciples mentally separate the spiritual gifts available in the temple from the exhausting rat race of performative righteousness that all too often stokes the alienation in the first place? For me, the answers that resonate lie in attempting to see Jesus and engage with his gospel more intentionally.

In Doctrine and Covenants section 70, the Lord put Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and others in charge of publishing the revelations that the Church had received through Joseph up to that point. In verses 2 and 3, the Lord says, “I, the Lord, have appointed them, and ordained them to be stewards over the revelations and commandments which I have given . . . and an account of this stewardship will I require of them in the day of judgment” (D&C 70:2–3). This idea of stewardship over spiritual things (as opposed to merely temporal ones) also shows up in the New Testament: in 1 Corinthians 4, Paul writes, “Let a man so account of us, as of the ministers of Christ, and stewards of the mysteries of God” (1 Cor. 4:1).

For me, the concept of spiritual stewardship suggests at least two things: first, it would be wrong to claim ownership over the spiritual gifts we’ve been given, either individually or collectively; and second, all of us are personally responsible to God for how we use the spiritual tools we have access to. Theologically speaking, none of us—not even the Church—owns the spiritual blessings of the temple. Yes, the Church pours the concrete and pays the electrical bills, but we make the promises and experience (or not) the spiritual fruits of living them. Choosing to serve in the temple and live the covenants is far less about our standing in the Church than it is about speaking with and worshiping God. Of course, Church leaders have been saying this consistently for years; the difficulty is that from a cultural perspective it’s unclear if we fully believe them.

So what are our spiritual responsibilities as stewards of the covenants we make? For me, regular temple attendance immediately comes to mind. I personally struggle to fit it into my schedule as often as I say I’d like; there are many worthwhile (and less worthwhile) things competing for my time and attention. I’ll go “when I need answers” or when I feel prompted to do so, but these instances are by definition both unscheduled and somewhat infrequent. Of course, we might conceive of more expansive spiritual responsibilities than just attendance: for instance, how should our individual stewardship of the temple influence our defining, daily interactions with spouses, children, and parents? How might they help us see even the most difficult people in our lives as children of God with infinite potential for giving and receiving divine love? If the temple is really as powerful as we say it is—if it is a place where God resides—our worship there ought to have transformative effects on our families, communities, and even the world. In a very literal sense, it ought to help us build Zion.

I first experienced the universal, all-inclusive potential of our temple worship a few years ago when I was one of the Latter-day Saint college students selected to participate in the Amos C. Brown fellowship program in Ghana. The Church partnered with the NAACP to make the trip in an attempt to build bridges of understanding, open lines of communication between people at all levels of the two organizations, and reckon with America’s legacy of racism and discrimination. Predictably, it was impossible to be in that space without pointed and valid questions about our church’s own history of racism and discrimination; there were many hard conversations as we joined with our college-age peers in the NAACP in trying to reckon with the trip’s vexing and complicated context.

Our itinerary didn’t make the experience any easier: on the second-to-last day of the trip we visited one of the slave castles in Cape Coast. The whitewashed walls shone in the sun, but the rusting cannon facing seaward spoke to the fort’s original purpose. Down in the bowels of the structure, below ground level and with only one remote window for light, we saw the pits where up to a thousand people at a time were kept in suffocating conditions for weeks before being loaded onto slave ships. It was explained to us that slavers sought to eradicate all traces of individual identity—whether relational, tribal, or cultural—by separating newly enslaved people from their families and treating them worse than animals. Since my dad came to the US from Rwanda and I don’t have enslaved ancestors, I wasn’t mentally prepared for the visceral, awful discomfort that enshrouded me. The intense darkness of the place far surpassed the physical dimness of the dungeon: it was the closest thing to pure evil I think I’ve experienced. I felt depressed, broken, and exhausted.

The next day, our last in Ghana, our schedule was open in the morning, and the Latter-day Saint students had the opportunity to go to the Accra temple for a few hours. As we began performing baptisms for the dead, I noticed that the names on the ordinance cards were all Congolese. I was struck by the unexpected but powerful parallelism. The previous day, we’d been in a place where African identity was ripped away and African families were torn apart; now, we were performing ordinances that treated the ancestors of living African Church members with dignity and reverence, symbolically honoring their lives and giving them a way to be united with their families forever.

In our theology, performing temple ordinances for the dead does not force them to become part of our church. Rather, it gives them the choice to posthumously accept the gospel of Jesus Christ and—we believe—gain access to the possibility of eternal life with those they love. It is a mark of honor and respect. My time performing these ordinances in the Accra temple became far more for me than a matter of personal faith practice—the hour or so I spent there morphed into a serious and important opportunity to participate in God’s work, extending justice and mercy further into a world that desperately needed it. We often speak in the Church of blessing the whole human family with our temple and missionary work, but never before in my life had I so clearly seen what that process might look like.

If our temple worship gives us unique opportunities to bless the world, it is uniquely our responsibility to put them to use. The ceremonies we perform there are not to be found in any other Christian tradition, and even if they were, no other faith tradition can speak our theological and cultural language quite like we can. The Book of Mormon teaches that God “speaketh unto men according to their language” and that he “doth grant unto all nations . . . to teach his word, yea, in wisdom, all that he seeth fit that they should have” (2 Ne. 31:4; Alma 29:8). These scriptures suggest to me a God who is acutely sensitive to the cultural and spiritual diversity of his children, sending forth divine light in numerous ways; however, they also suggest to me a God whose desire to bless us is contingent on our willingness to understand and engage with the spiritual truth available to us. If the temple really is what it claims to be, we as Latter-day Saints have inherited a deep, undeserved and priceless vessel of heavenly light. In that case, what we choose to do with it is genuinely important.

While I hope I’ve made the case that the temple can have symbolic and spiritual meaning far outside our Latter-day Saint tradition, I still haven’t addressed its potential as a source of alienation for those inside it. What does our spiritual stewardship have to say about this? Several thoughts come to mind.

Given what the temple offers, it seems reasonable that the question of who gets to participate in the ordinances is something for which our entire church will ultimately be held accountable to God. I have often reflected on the fact that if I’d been born forty years sooner, I wouldn’t have had access to the temple for reasons beyond my control. More vexingly, it wouldn’t surprise me if in the future I lose the access I currently have due to my desire for human connections of the sort that the Church does not recognize. Although it might seem strange, neither of these things leads me to question the temple’s underlying legitimacy. Explaining why not could be an essay of its own, but the shortest reason I could give is that I’ve had enough profound temple experiences to firmly believe that the divine power I experience there is real. It influences my life in ways that both sanctify and enhance my self-conception as a child of God. The pain that I have felt and may yet feel because of these difficult questions is pain that I believe Jesus has already suffered on my behalf. Choosing to mentally invalidate or ignore the profound spiritual experiences I’ve had wouldn’t help me to face the apparent contradictions I live in with any greater equanimity; paradoxically, fully embracing my spiritual heritage has given me the ability to think productively about questions that would otherwise be far too difficult for me.

On a more general level, it is perhaps unwise for us to let ourselves conceive of the temple doors as being meant to keep people out. Just as we might go to a grocery store to pick up food for someone who is housebound, we could probably get better at “translating” the light and truth we can receive through temple worship into the lives of everyone around us—members and nonmembers alike—who cannot at the moment access it for themselves. If the temple gives us added strength to cope with our individual challenges, our baptismal covenants remind us that at least a part of that strength ought to go towards bearing the burdens of others. Stewardship is not ownership. Since we do not own the temple, thinking of its power purely in terms of our own spiritual health (or worse, as part of one of our seemingly unending righteousness checklists) is misguided and profoundly stifling.

Jesus memorably taught, “Men [do not] light a candle and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house” (Matt. 5:15). For us as Latter-day Saints, the temple is perhaps the most salient mechanism for dispensing the light that can come into our lives through the teachings of Jesus. In a world that seems more chaotic and confusing each day, our quiet, consistent ability to project that kind of light into our families and communities is increasingly important. Whether or not we hold a temple recommend—whether or not we fully feel as though we belong in our wards or in the Church—we can all do more to cultivate our relationship with Jesus through the indescribable spiritual gifts he has given us. We can intentionally fill our lives with his love, sharing it with others along the way until one day we step back into his presence and find ourselves truly, perfectly, and eternally at home.

Peter Mugemancuro is an undergraduate at Stanford University, studying economics.

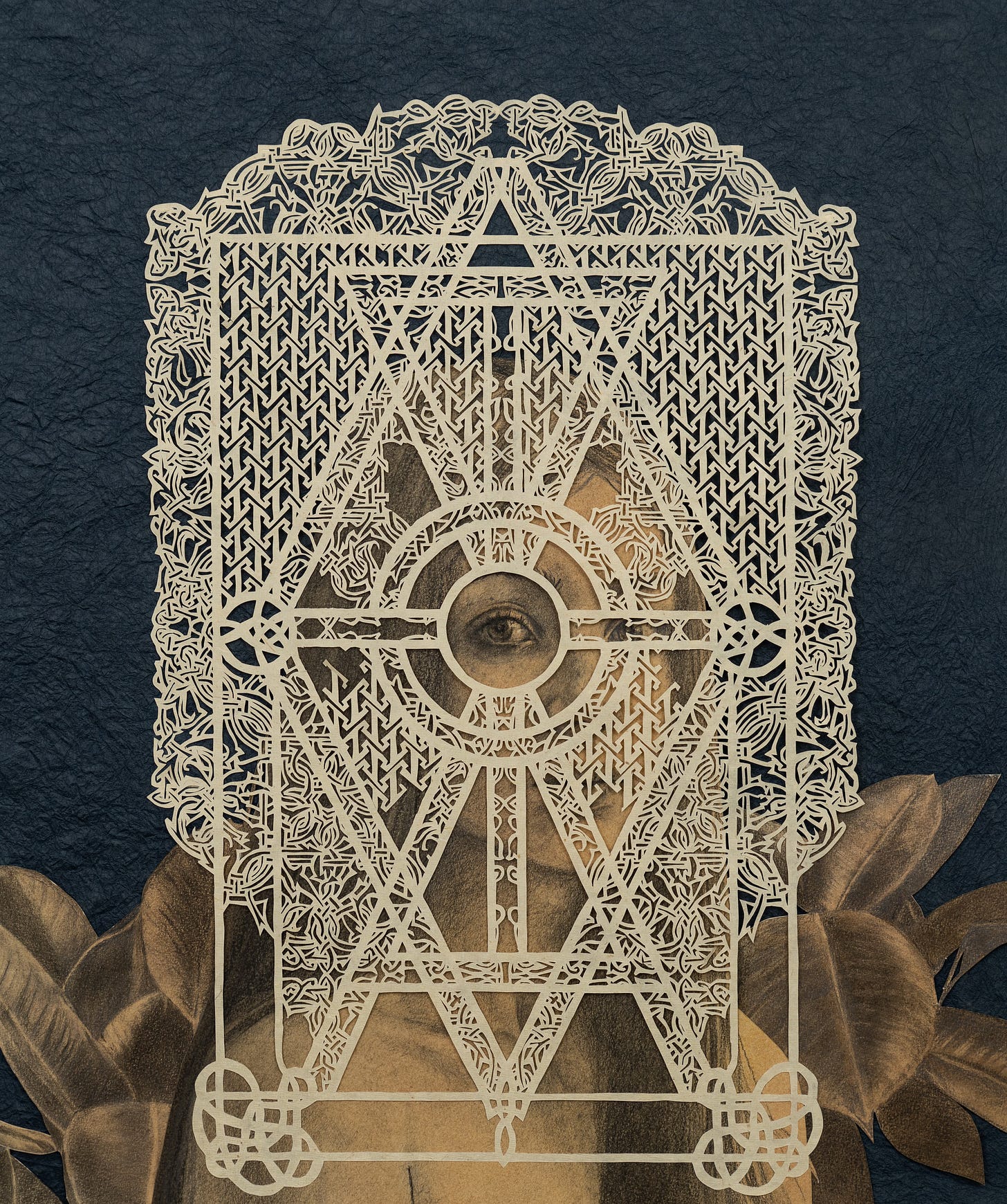

Art by Elise Wehle.

Beautiful thoughts on a rich and elusive topic. Thank you especially for sorting through the perceived “in” or “out” dichotomy of who the temple blesses. Your ability to reconcile times when you could not have / may not be able to access the temple with your continued faith in its authority as a House of God is an insight I’m grateful to have read. Thank you!