Even after years in the Church, Heshel had never paid a fast offering.

From a certain perspective, of course, he had always paid fast offering. The missionaries had taught him fast offering was intended to match the value of any meals a person missed on Fast Sunday. Since none of Heshel’s fasts had ever lasted all the way through a mealtime, the nothing he had given was fully equal to everything he had saved. But still, Heshel found it embarrassing that he could barely fast through his Church meetings, let alone the Sabbath. Someday, he had resolved for years, he would find a way to make himself do more.

It happened one year, at last, that Passover was to begin in the evening at the end of a fast Sunday. And so it was that, to prepare for the holiday and help Heshel with his long-stated goal, Clever Gretele decided to clear not only everything leavened but also all food of any kind from the house, so her husband could finally make it through his fast.

Heshel was terribly impressed with his wife’s cleverness. He thought of little else as he wandered the house, absently opening cupboards in the reflexive search for some morsel of meal to eat. But there was not even so much as the widow of Zarephath had shared with Elijah. Though his stomach growled as loudly as the she-bear once summoned by the prophet Elisha, Heshel felt proud of himself, and still prouder of his wife, that evening. Before going to bed, he even took a moment to calculate what he might pay for his first fast offering.

Unfortunately, it appeared his contribution would be meager. Since Gretele had cleared out the house for Passover, what Heshel was not eating was bound to have been mostly matzah. He asked Gretele to count out some coins for the skipped mouthfuls of stiff, flat flour, but it turned out she only needed one. Heshel imagined he would do better another year, or perhaps decade. With time and discipline, he was sure he could gradually build up to not eating leavened bread, and from there perhaps to not eating blintzes, and someday even progress to not eating his mother-in-law’s heavenly babka.

His whole body rebelled at the thought.

Heshel did not sleep well that night. Dreams of skinny cows and empty babka trays left him tossing and turning. In the morning, Heshel woke bleary-eyed and famished. He began fantasizing about making a tall stack of matzah French toast.

Heshel smiled. Perhaps his fast would not be so modest after all! “Gretele,” he whispered urgently. When she only snored in response, he gently shook her shoulder.

“What is it?” she asked him, squinting in the general direction of their bedside clock.

“How much would it cost to buy a box of matzah, a half-dozen eggs, a half stick of butter, a pinch of cinnamon, two tablespoons of syrup, eight fresh strawberries, and a cup of whipped cream?”

“Go back to sleep,” Gretele said. And then she led, as the Savior taught, by example.

But Heshel couldn’t. The combination of his growing enthusiasm and gnawing hunger propelled him out of bed. After some careful calculations, he counted out more coins for his fast offering while humming “The God of Israel Neither Slumbers Nor Sleeps.”

By the time the family stumbled out the door toward Church late that morning, Heshel had added coins to his fast offering two more times as his plans for the breakfast he was skipping expanded. He went back into the house to add coins yet again as soon as he realized that he was hungry enough that, were he not fasting, he might beg Yossel the Fisherman for a bit of his latest catch.

Heshel could not believe the rate of his progress. Over the course of a single day, it seemed there was more and more he was not eating. The only time he backslid was during the sacrament, when he slipped a small coin back into his pocket to offset the value of the tiny piece of matzah he took when they passed the tray around.

But in the battle with his increasingly ravenous hunger, the sacramental matzah did little to turn the tide. Heshel wanted a mixing bowl filled to the brim with potato salad. He wanted scoops of haroset the size of his fists. He was willing to eat even gefilte fish, if it came to that, to satiate his poor stomach!

As he made his way toward elders quorum, Leah Kantor stopped to ask him how he was doing. Beaming with pride through his abdomen’s rumbling screams of protest, he told her he was successfully fasting for the first time. When she asked if he was feeling hungry, he blurted out that he was so famished he could eat a horse.

As the implications of that comment sunk in, Heshel realized he had reached the point in the pride cycle the Book of Mormon was intended to warn against.

Still, honesty was the best policy. When the discussion in elders quorum had strayed enough from the point to make whatever questions Heshel might ask sound average, he sheepishly raised his hand.

“How much does a horse cost?” he asked Brother Cohen, who was teaching that week.

“The price would vary greatly,” Brother Cohen replied. “Are you asking about a draft horse? Or a thoroughbred racer?”

Heshel shrugged. “Just a regular eating horse, I suppose.”

Oskar the Miser raised his hand immediately. Heshel winced as he quoted the price. The Miser’s insistence that the meat from one horse could last a family like Heshel’s well over a year, after whatever wedding or other occasion they were celebrating, was cold comfort.

Heshel briefly considered walking away from the Church building and simply following the sun until he found yet another town to settle in rather than face Gretele with the news of what they would be paying in fast offering. But while the scriptures gave permission to flee from one’s father and mother, they were express on the matter of commitment to one’s wife.

Heshel then briefly weighed God’s potential wrath against Gretele’s. While it was true he had said he could eat a horse, he might pretend he had meant only a horse-shaped cookie and never have to tell Gretele he had incurred such a substantial divine debt over the course of a single day. But of course God would know and might tell Gretele sooner or later in any case.

And so it was that Heshel resolved to do what was right and let the consequence follow. He told his wife the truth and the whole truth, albeit in a roundabout way that began with his conversion years before and continued through visions of matzah brei and mackerel until the words tumbled out all at once about how he had never intended to be so hungry but had found a certain truth revealed in a passing conversation on his way to elders quorum.

Gretele listened stoically as he related verbatim how he had asked after a horse’s price and shared the somewhat dated but nonetheless daunting figure Oskar the Miser had quoted him.

Gretele let out a long, weary whistle when he was through. “I believe,” she said, “that we will spend as much on your fast offering today as we have on mine all these years.” She opened a drawer and withdrew a succession of silver: earrings and necklaces, rings and pendants, candlesticks and spoons. “The Lord giveth,” she said, “and the Lord taketh away.”

Heshel looked at all the silver she offered and shook his head. It was too much, he explained, well beyond the price of a simple meat horse.

“Will a man rob God?” Gretele replied. “We should err on the side of generosity. Let’s pay for an Arabian.”

Heshel trudged back to the Church, his fast offering bag heavy as Benjamin’s sack but his heart feeling surprisingly light.

Bishop Levy thanked him profusely. In the rush of the holiday, the bishop said, no one else had remembered to turn in their fast offering that day. Heshel was the first.

After Heshel left, Bishop Levy called in Lazar the blind beggar. By longstanding arrangement, Lazar—who insisted on living only by the grace of God—was given the first fast offering of the month, no matter how modest or generous it might prove to be.

But for all his boundless faith, nothing had prepared the Blind Beggar to receive God’s grace in such equine proportions. “Bishop,” Lazar said after the clerk finished counting the money, “Send out the word through the ward. Call the other beggars off the streets! On the last night of Passover this year, I want to invite everyone to the meetinghouse for a sumptuous seder feast.”

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

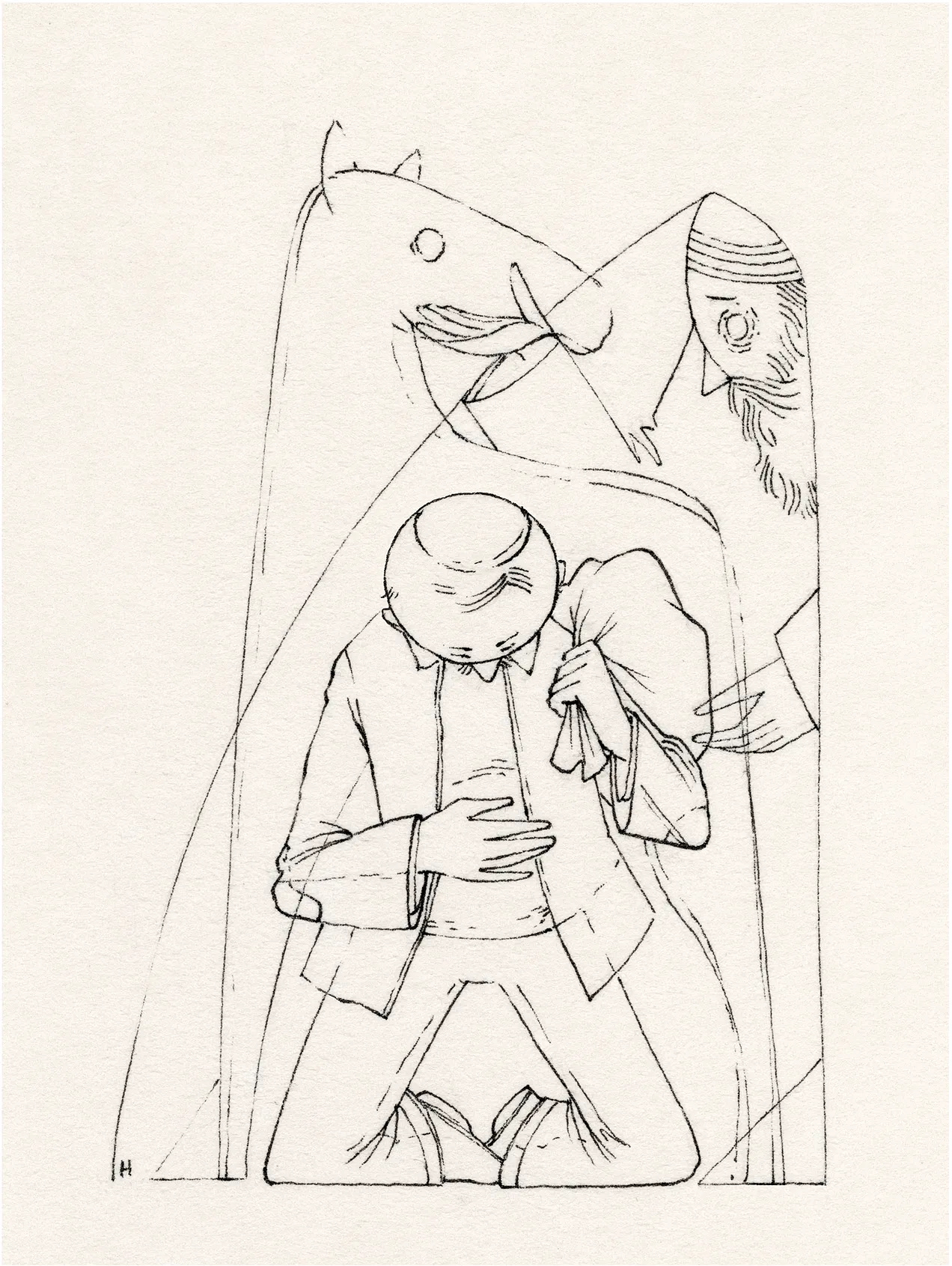

Artwork by David Habben.