Hearts Shall Turn to Their Mothers

Finding Healing in Family

There is strength in family history.

In 1916, Pancho Villa crossed the United States border and raided Columbus, New Mexico. His men captured horses, mules, and military supplies before returning quickly to Mexico. In reaction to Villa’s attack, President Woodrow Wilson sent General John Pershing with thousands of U.S. troops to enter Mexico, find Villa, and punish him. Pershing led the chase through northern Mexico right into the heart of Chihuahua, where Mormons lived at Colonia Juarez and Colonia Dublan. These colonies became strategic points of interest for Pershing as he gathered intelligence from Mormons on Villa’s whereabouts.

One night, a garrison entered Juarez to see Joseph C. Bentley, the community leader. On Bentley’s front porch, or maybe inside in the parlor, the garrison’s leader told Joseph that Villa was killing Americans in Agua Prieta. The next target could be Juarez. Joseph gathered some belongings and left with the garrison in the dark of the night to post citizen guards around the town’s borders. These guards lit campfires everywhere they could.

Back at Joseph’s home was Maud Mary Taylor Bentley, who heard the garrison report from under the bedcovers. Maud was Joseph’s third living wife at the time. “Shaking like a leaf,” she rose from bed and walked outside to the barn, found a small ax, and positioned herself at the front of the house on a chair, scanning the fire-illuminated horizon. She had a household to protect.

I found this story a couple of years ago in Maud’s autobiography: a thin, blue, hardcover book given to me by my grandma about twenty years ago. My grandma is Maud’s granddaughter. The autobiography’s title page reads:

Sorrows, trials and tribulations, Triumphs, success and happiness On the Frontiers in Old Mexico

I invited the kids to listen as I read to them from Maud’s book. For a few weeks it was our bedtime reading as we circled around her book on the floor together.

My children learned that Maud was born in a covered wagon and raised in an adobe home with a pounded dirt floor. At Juarez, she was considered rich relative to other families because her parents afforded her milk and flour instead of the more prevalent cornmeal. We learned about Maud’s experiences helping carve out orchards and farms while raising chicken and livestock. And the kids learned that even then, generations ago, the community supported regular school attendance in the midst of all that colony-building.

On holiday, Maud enjoyed picnics with family and friends in the cool of the mountains surrounding Juarez. These picnics were two-week affairs fueled by fresh venison and trout from the streams that came out “by the buckets.” Buckboard wagon races brought Maud local fame at these gatherings—she even calls out a young Julius Romney in the book, whose buddies razzed him for losing a wagon race to Maud.

As an adolescent, Maud appreciated the geography of her land. She enjoyed climbing trees, throwing rocks, and running faster than the boys, her red braids flying behind her. She was known as the “freckled face sorrel top.”

She grew up fast, though, because the colony supported the practice of polygamy.

Maud married Joseph Bentley on September 23, 1901, when she was sixteen. He was forty-three. “Some difference,” she wrote. He had courted her by asking her to dance at the town’s “quadrilles.” She was “humiliated to death” in front of her friends. He’d also wait at a specific street corner on her school route so he could engage with her. She found that peculiar and unwelcome. She hated the teasing from her friends. With Maud showing only minimal interest, Joseph went to her father and declared that he wanted to marry Maud for his third wife.

Joseph was kind and he could provide. He settled Maud into a three-room lumber home, fully furnished and wallpapered, with a front yard full of almond trees, walnut trees, grape vines, and flower beds. She would later write of Joseph: “I came to love that man.” Maud grew into her role as wife, mother and homemaker and took care of many in her community.

Ten years ago, I needed help for a very active and severe eating disorder. I was dying, and the collateral damage my behaviors inflicted on family, friends and colleagues was extensive and growing. So, I resigned from my job as a doctor in training, left my wife and daughter (unsure if the marriage would last) and enrolled at Rosewood, a residential treatment center in Wickenburg, Arizona. After ninety days, I was discharged to outpatient care, and Anna, seeing me healthy for the first time in our marriage, allowed me to come home to her and our daughter. Life moved forward. I finished medical training, and we were blessed with three more kids.

An eating disorder is insidious. So insidious that it has a higher mortality rate than any other mental illness or condition. Over the last few years, the insidious patterns returned as part of my day-to-day coping. Anna told me I was looking ill again. And so here I am again, ten years later, working again on my health and recovery.

Oh, God, why can’t I beat this?

Family and friends continue to offer support. I’m blessed. But the weight of the illness is heavy. I’ve been surprised by the moments when Maud’s stories come to mind, helping me lift some of the weight. Driving home recently from a difficult, tense day in clinic, I remember Maud’s recounting of her experiences as the only nurse in Juarez. She nursed everyone, native and non-native, taking care of pneumonia, dysentery, and poison ivy. She lost “hundreds of nights of sleep” taking care of her family and community during the flu epidemic. Instead of sleeping, she was “poulticing, steaming, rubbing, packing.” Thinking of her nursing work on my drive home made it easier to drink the protein shake sitting in my lap.

If you understand anorexia, you know that starvation brings alertness and energy. To eat is to lose that reliable source of energy. I miss the energy as I eat regularly, but at the same time I’m trusting my body will realign with its God-given, natural biorhythms. And I now quite often find strength by thinking more of Maud’s story:

I used to get three babies to sleep every night. I would have the rocker close to the bed . . . Franklin in my arms, Joseph close to my stomach and Lavinia on my knees.

When I’m tired, I picture Maud there on her rocker, plastered with babies needing sleep. I can do this work.

I called my mom not long ago and told her how Maud’s book was helping. Talking about Maud seemed to help us skip small talk and focus on our feelings, fears, and fantasies. I told her I appreciate her resilience working through her life’s challenges. Mom and I are so alike—and that sameness has lately felt less like a thing to be avoided and more like something to lean into. The phone call was grounding and nourishing.

Elder D. Todd Christofferson recently spoke about what happens when hearts of children and parents don’t turn to each other:

It is this free-floating, disconnected state of individuals . . . that would frustrate the very purpose of the earth’s creation. Were that to become the norm, it would be tantamount to the earth being smitten with a curse or “utterly wasted” at the Lord’s coming.

Christofferson was speaking of priesthood sealings connecting individuals. Maybe the storytelling is the prelude, if not the prerequisite, to the sealing work. The storytelling provides the bricks to build our family history.

When I look up my family tree, I remember nourishing connections. I remember Grandma Hansen sitting next to me at the dinner table when I was eight, hugging me and telling me how handsome I was during a scary, anxious time of my life when I was too shy to look at people, much less talk to them. I remember Grandma Budge telling me to “get on in here, Spence,” when I’d visit during my lean college years. She lived just down the road from the university and always had a much-too-warm living room and tasty meal waiting for me. As I look up a branch on my family tree, I remember sitting in a house in Idaho near my mom as she carefully held my Great-Grandmother Wuthrich’s hand, like it was made of glass. In my memory, the sun is shining through a coke-bottle kitchen window and a rotating sprinkler is going “rat-tat-tat” around the back lawn. I remember Grandma Wuthrich speaking slowly, softly, my mom listening with attention and presence. I’m strengthened by these memories.

A few years after Maud passed away in 1976 and two years before I was born, Elder Hartman Rector gave a talk in General Conference titled “Turning the Hearts.” He said:

I am sure you will never turn your own children’s hearts more to you than you will by keeping a journal and writing your personal history. They will ultimately love to find out about your successes and your failures and your peculiarities. It will tell them a lot about themselves too.

I like to daydream that Maud and I were sitting together somewhere in heaven, listening to Elder Rector. I like to think she told me where to find my own ax for my long, dark, threatening nights out on the frontier. Perhaps she told me not to fight the fight alone. She didn’t have to fight alone—she had God and family. When Maud spent that night guarding her home, ax in hand, she must have felt courage as she watched the night sky light up with the fires of the citizen guards. It is thought that Pancho Villa recalled his army when he saw these many fires, which he took to be fires of Pershing’s federal army. Maud wrote, “It was the power of the Lord that made him see all that.”

I can’t wait, with turned heart, to find Maud someday and confirm yet again the truth found in her patriarchal blessing:

Even you shall feed the hungry in the time of scarcity of food. Your basket shall not be empty and your heart shall be supplied with the sympathy of the distressed.

Spencer Hansen, born and raised in Mesa, AZ, currently lives in Salt Lake City with his wonderful spouse and four kids. He's a physician working for Intermountain Health. He'd love to hear your thoughts and experiences—your trials and triumphs. You can reach him at shansen3@tulane.edu.

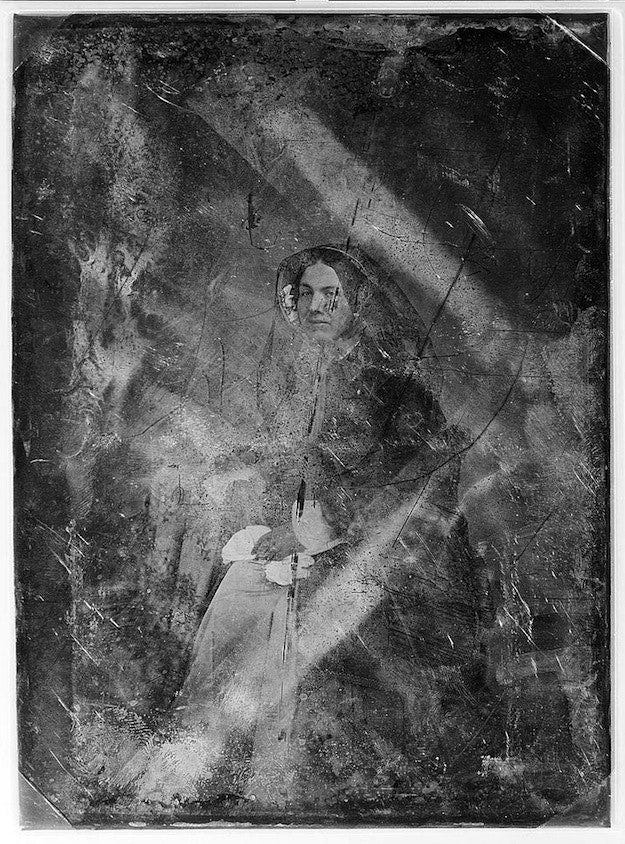

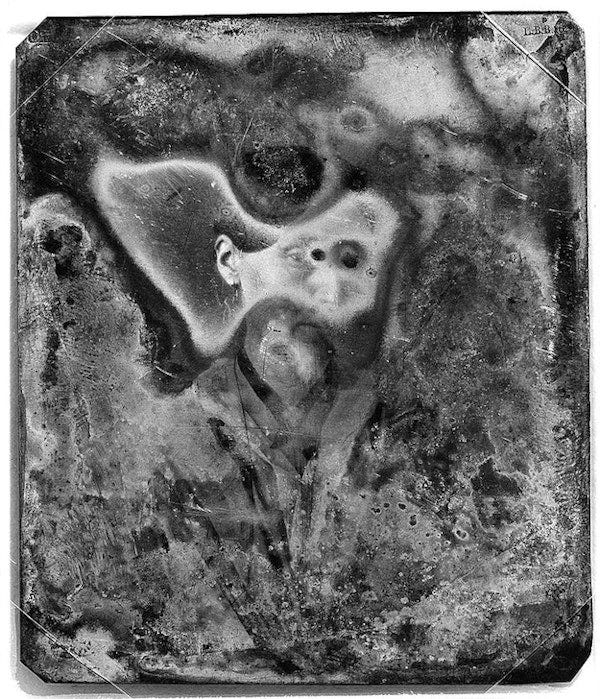

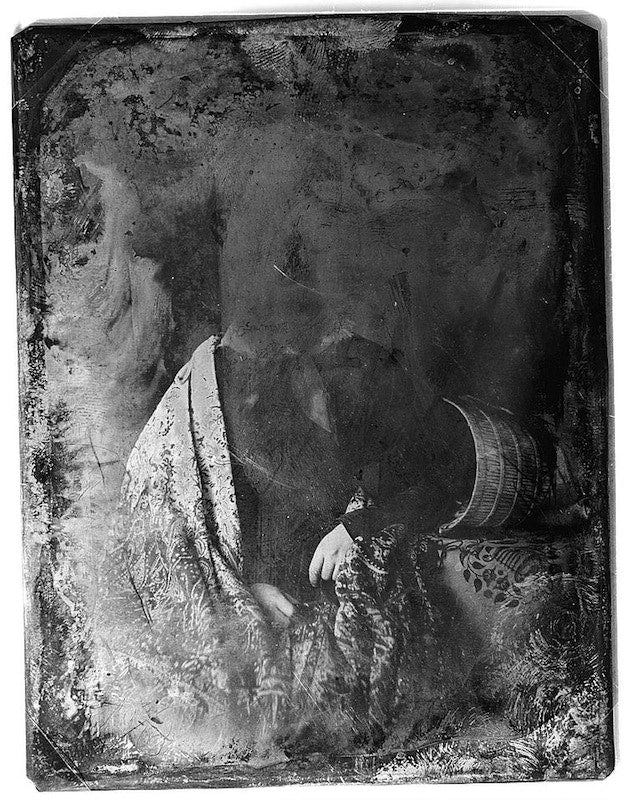

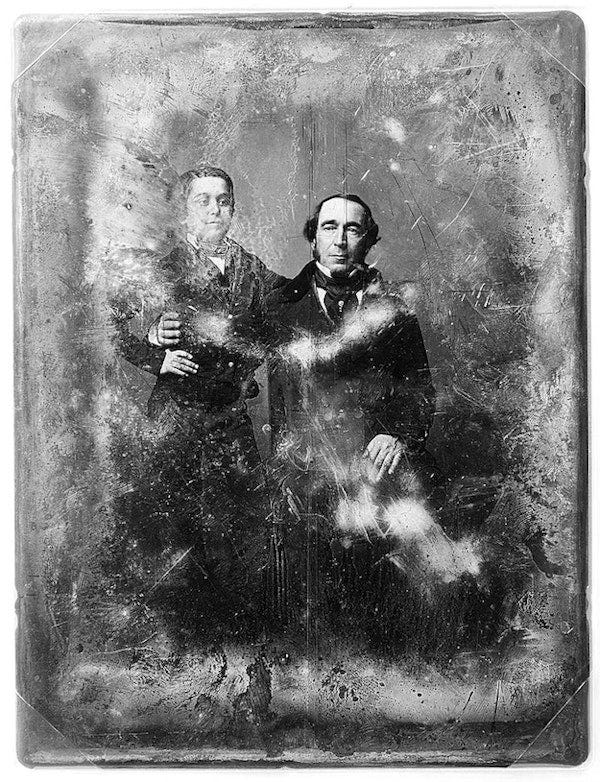

Art by Matthew Brady

Well written! Good for you!

Spencer, this is such a lovely piece. Honest, warm and wise. I love how Maud's book has enriched our lives and those of our children. I love your thoughts and the strength you've felt in knowing Maud's remarkable life. Thank you! Carolyn (and your great uncle Marion) Bentley.