God with Us in the Texas Flood

In the pre-dawn hours of July 4, 2025, a section of the Guadalupe River in central Texas flooded. The water rose more than twenty feet in a matter of minutes, and one of the epicenters of its devastation was a Christian girls summer camp known as Camp Mystic. The cabin with the youngest campers, affectionately known as the Bubble Inn, took the hardest hit. This particular cabin near the river held the eight-year-old girls—Camp Mystic’s “littlest souls”—and not one of them or their counselors survived. All of Bubble Inn’s fifteen inhabitants that night perished or disappeared with the flood waters.

I have two girls who are both about this age; I know the innocence and the fears of eight-year-old girls. This is the age when monsters under the bed are still a tentative possibility. When they still might need a parent’s hand as they walk into a new or unfamiliar environment. So the panic and darkness and horror of the rising water in the hours or minutes before they drowned—that is the place that gives me the most agony as a mother. Imagining those little girls as they faced a monster that they couldn’t escape, a monster that would completely overtake them. It’s a real-life horror that is unfathomable. This is no movie drama with an intense climax leading to a miraculous rescue. Their story moved soberly from the catastrophic to the inevitable, with who-knows-what mortal terror in between.

In the midst of reading their stories—my heart bursting with sadness—I grappled with how I felt and what I so desperately desired. I ultimately concluded it was this:

I wanted to be there with those girls in their final moments of terror.

Time is an interesting thing. According to human chronology, the flood happened in July of 2025. That is now part of the chronological past. There is no way for me to access those girls in a mortal world without time machines. It’s not a distance problem, it’s a chronology problem.

But our God is a God without limits of mortal time. One of his self-proclaimed titles is Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, without end of days or beginning of years. There are many examples in canonized scripture that clearly delineate an omnipotent being who is not constrained by mortal time. He can come to us and succor us wherever and whenever we are.

As mortal beings, of course, we do not enjoy the luxury of living outside of time. But as God’s children, we do get to experience moments of transcendence where we see the power of God working in mysterious and inexplicable ways. Furthermore, as part of his great plan, he has made it clear that our destiny is to become like him.

So how do we become like God?

Bob Goff, in his book Love Does, has an idea: “Jesus is sometimes called Immanuel— ‘God with us.’ I think that’s what God had in mind, for Jesus to be present, to just be with us. It’s also what He has in mind for us when it comes to other people” (8).

Psalms 34:18 reads, “The Lord is nigh unto them that are of a broken heart” (KJV). The Message Bible renders it differently: “If your heart is broken, you’ll find God right there.”

If your heart is broken, you’ll find God right there.

You’ll find God right there in the storm, in the fire and the torture and the agony. He told us that our agony is his agony—the central tenet of all Christianity is that he took it upon himself. As Terryl and Fiona Givens have pointed out, “God is not exempt from emotional pain . . . On the contrary, God’s pain is as infinite as His love.”

So it would stand to reason that at least one of the steps to godhood involves being present in others’ suffering as he is present in ours. Sometimes healing, but more often than not just witnessing. Mourning with a heart that is mourning. Knitting our heart together with someone else’s heart. Knitting—with its sharp jabbing and poking needles. Binding our infinite string with another’s infinite string to form something new and beautiful.

What if the possibilities of Zion were already here, and its scattered elements all about us? A child’s embrace, a companion’s caress, a friend’s laughter are its materials. Our capacity to mourn another’s pain, like God’s tears for His children; our desire to lift our neighbor from his destitution, like Christ’s desire to lift us from our sin and sorrow—these are not to pass away when the elements shall melt with fervent heat. They are the stuff and substance of any Zion we build, any heaven we inherit. God is not radically Other, and neither is His heaven.

―Terryl and Fiona Givens, The God Who Weeps: How Mormonism Makes Sense of Life

If God and his heaven are not radically other, then it would stand to reason that none of his children are other. In that way, those babies who drowned in the Texas flood were my babies. Those eight-year-old girls are my girls—not in a possessive sense, but in a Zion sense of being one heart and one mind. Their suffering (and their parents’ suffering) is mine to bear as well, if I am willing to take it on.

So how do I take that on? For the victims of the flood at least, it’s too late. Their valley of the shadow of death has passed and they are safely in the arms of Jesus. I believe that with all my heart.

Yet still, there was something inside of me that yearned for a place to channel all the grief I felt at their moments of terror before the end.

The answer took me in a direction I didn’t expect: prayer.

First I have to first confess my weak spots when it comes to prayer: Do I believe prayers can cure cancer, help people find jobs and change hearts? Sometimes.

A second weakness of mine is my slight stigma I’ve attached to phrases such as I’ll be praying for you. I know such phrases are well-intentioned. But they can sound so trite, so neatly packaged and tied with a bow. Prayers will screw in those lightbulbs and make the darkness go away and everything will soon be bright and cheery and crystal clear again.

The certainty of it all can be disconcerting.

Now I view prayer as more mysterious than I did as a child (where I prayed to find things like my missing homework and then—poof—it was found). Prayer is not a magic poof. It’s not a magic anything.

If anything, prayer for me is a state of in-between-ness that feels equal parts confessional, complaining, grateful, and tentative.

So while I believe in prayer, I struggled to see how it could help. This tragedy occurred far away and in the past. I could pray for the families who’d lost loved ones, but what could I do for the girls? Chronology had me stymied.

I believe that prayer can change our circumstances. I believe that prayer can transcend geographic and linguistic barriers. And if I believe those things, could I believe the power of prayer could transcend our mortal timeline?

These words from C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity gave me a sort of blueprint for what I experienced next, something that I would describe as both the map with directions and the knowledge of the treasure in the first place:

An ordinary simple Christian kneels down to say his prayers. He is trying to get in touch with God. But if he is a Christian he knows that what is prompting him to pray is also God: God, so to speak, inside him. But he also knows that all his real knowledge of God comes through Christ. . . You see what is happening. God is the thing to which he is praying—the goal he is trying to reach. God is also the thing inside him which is pushing him on—the motive power. God is also the road or bridge along which he is being pushed to that goal.

So that afternoon, I did something I had never even considered as a possibility: I prayed to have permission to be there with the girls who drowned in that flood, those littlest victims in the Bubble Inn of Camp Mystic.

I felt like in doing so, I was participating in this three-fold process that C.S. Lewis described: my heart was being acted on to feel for these girls in the moment of their greatest panic. I felt a transcendent pull into a higher state of mind, one that wanted to be present (as God is with us) in that moment with them. I felt His invitation to ask for that in my prayer.

And so I asked.

I bowed my heart and my soul and asked God to let me transcend time and space and lend my strength and my love and my compassion to those drowning girls’ final moments. I pled to have the unspeakable grief and empathy I was feeling transformed into something that could be—that could exist—in another time and sphere as some sort of help or solace in those final moments for those girls.

Words can’t quite describe how I felt—a wrenching of my whole soul, at times making it impossible to speak. While I cannot testify of anyone’s experience but my own, I can testify of this: our God is a God who weeps. And for that hour, I joined in his work. Or perhaps he joined me.

Several of the news articles noted that the selfless and aging owner of the camp, Dick Eastland, had rushed to Bubble Inn early on the morning of July 4 to try and save Camp Mystic’s “littlest souls.” Tragically, he didn’t survive either; he was found near the bodies of three of the girls he was trying to rescue and reportedly died en route to the nearest hospital.

To save and to rescue is always the goal, isn’t it? I don’t know if it’s our human nature or our divine one that compels us to be rescuers. But nevertheless, there come times into our lives when we can’t rescue—when our respective constellations of geography or chronology make doing even a single thing an impossibility.

And yet, based on this personal experience, I believe there is something that is left for us to do, something that has untold power to transform us and take us into sacred corridors of godliness.

We can be present with another’s suffering—past, present, or future—through the sacred channels of God’s Spirit. These channels are not constrained by mortal constructs of time or space, and are ultimately the same sacred channels through which God promises to be unfailingly and eternally with us:

When through the deep waters I call thee to go, The rivers of sorrow shall not thee o’erflow, For I will be with thee, thy troubles to bless, . . . And sanctify to thee thy deepest distress.

Jessica Wiest loves teaching high school writing courses at the K-12 school where her five children attend. In her spare time, she loves food, games, reading, and talking to people. She has given up trying to keep her garden alive.

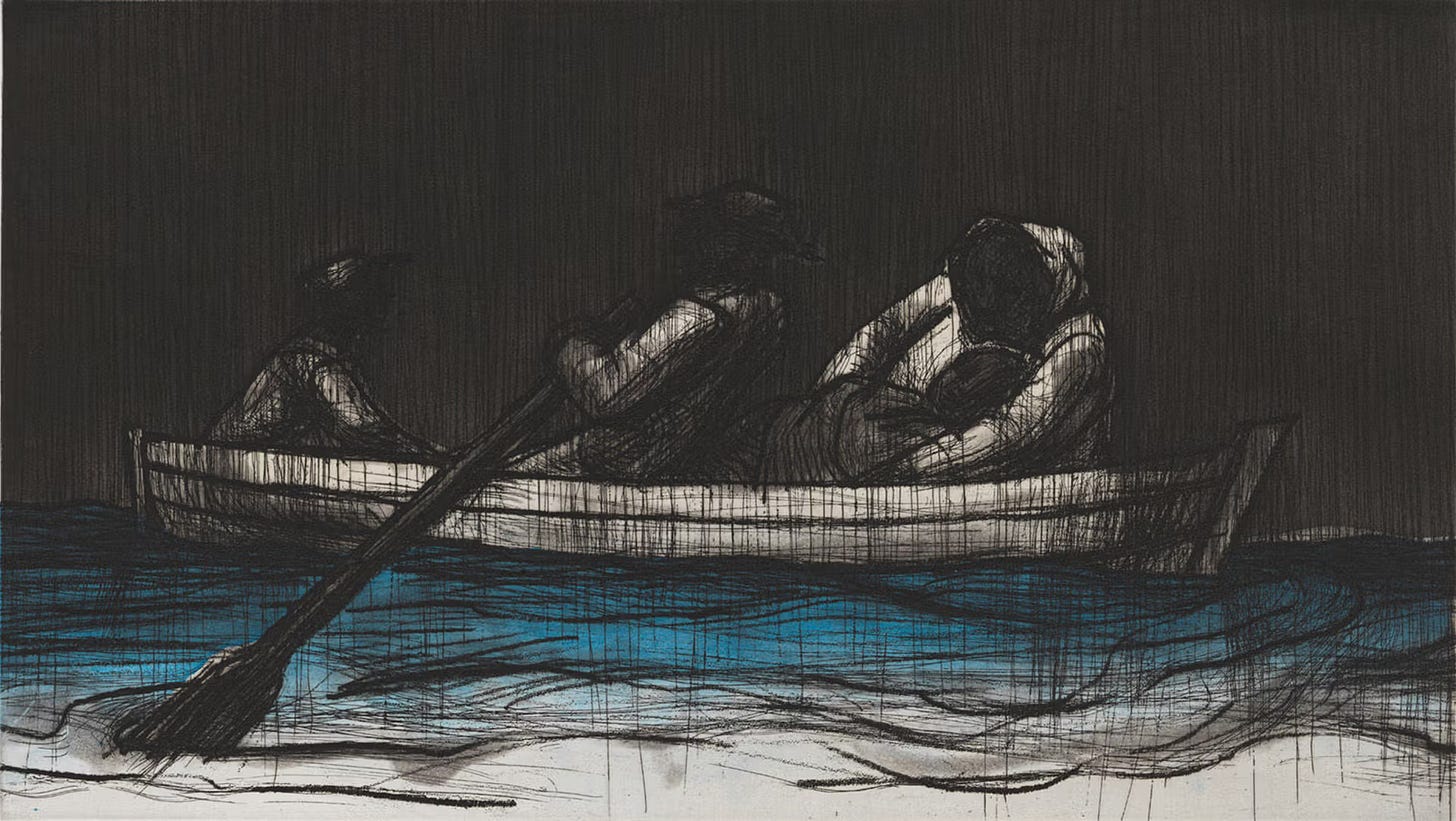

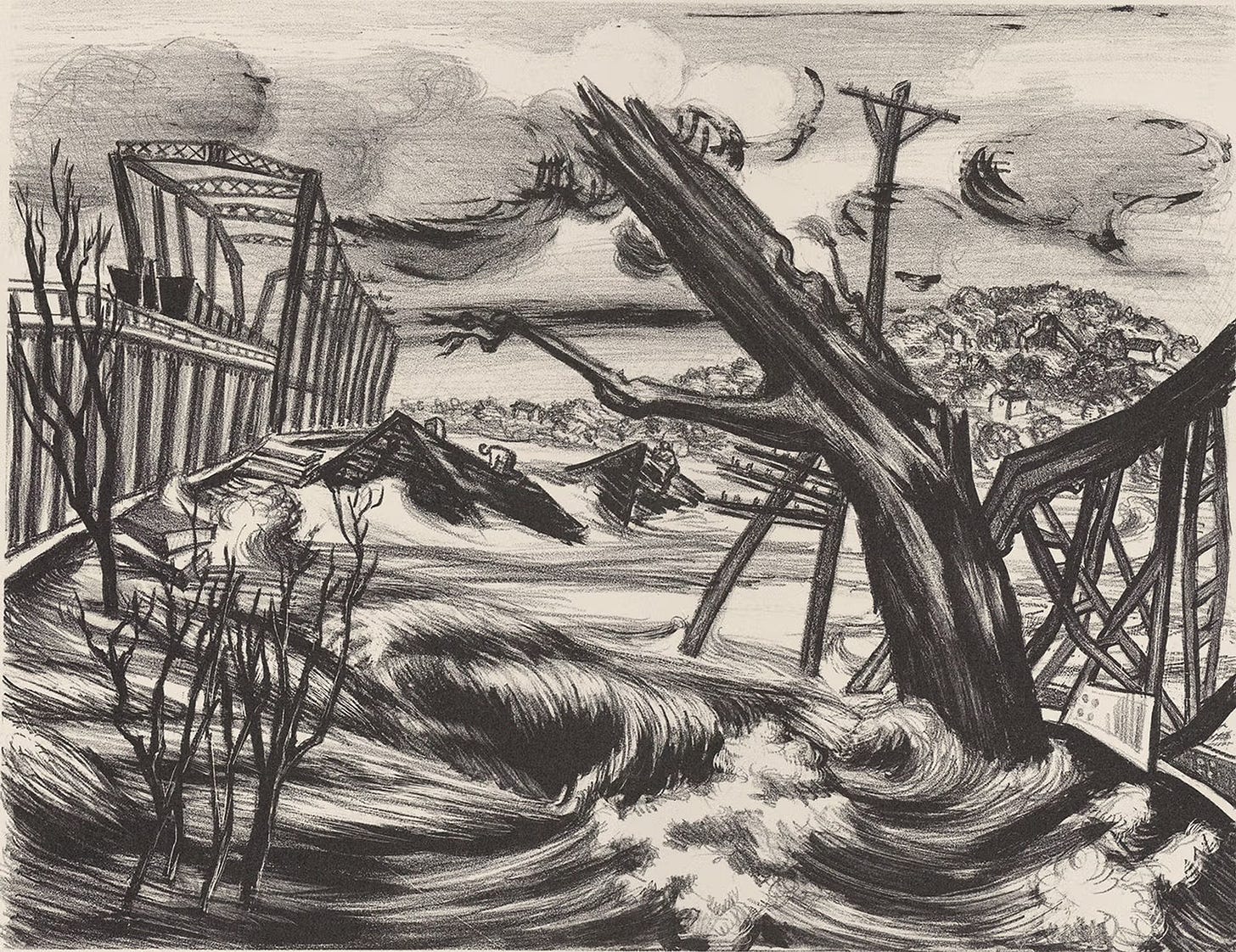

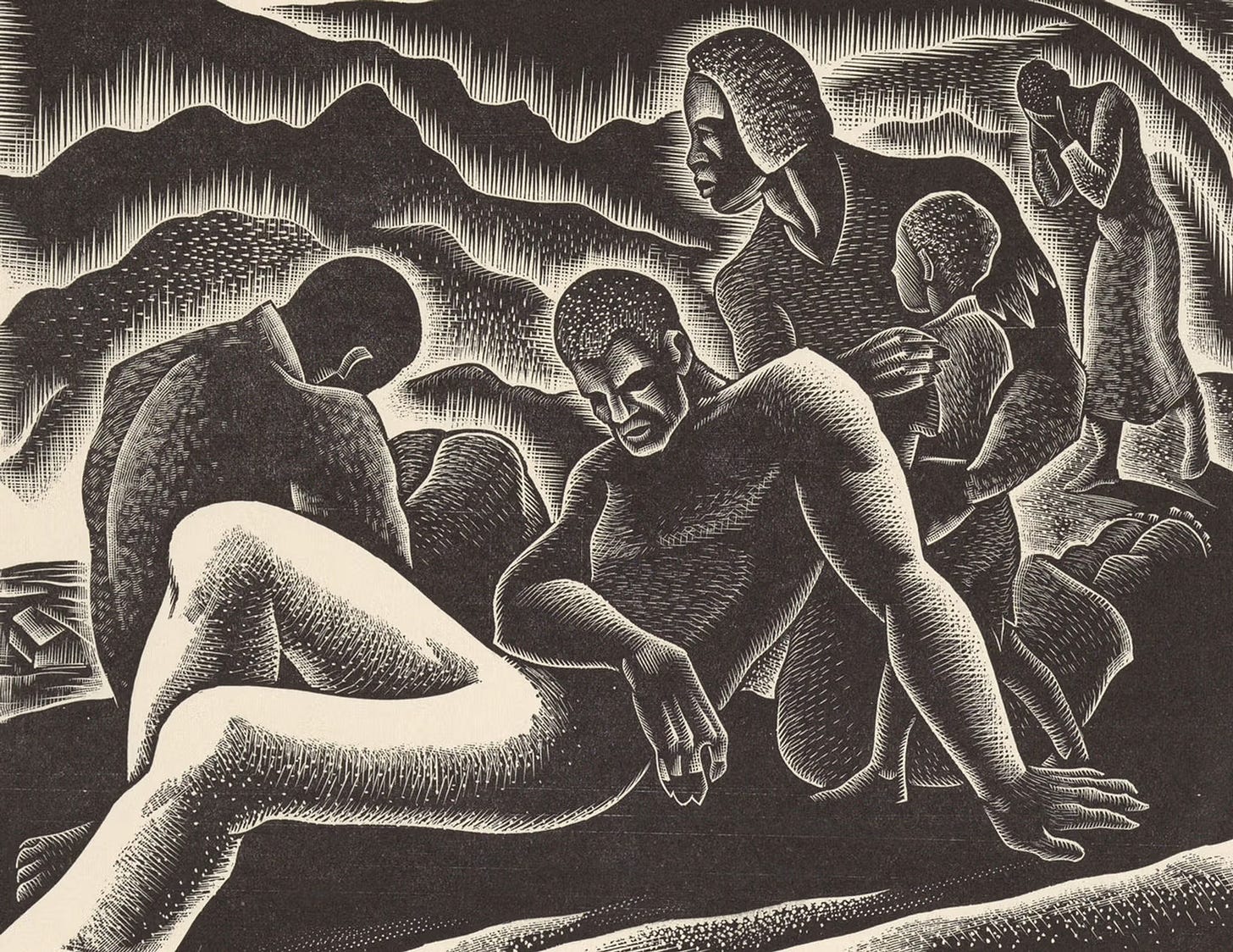

Art by John Wilson (1922-2015), Jacob Kainen (1909-2001), Donato Rico (1912-1985), and Edgar Imler (1890-1973).