God Is Bigger

How Eugene England, Bruce McConkie, and Many More Are Equally Part of the Body of Christ

I believe that one of Paul’s most potent and well-known metaphors, the body of Christ, can be instrumental in helping us make sense of long-simmering Church conflicts that cause great pain and are in desperate need of healing. If we look closely, we may find that elements of the Church that appear to be at odds with one another may both simultaneously be inspired, with all involved trying their best to be like Jesus—whose grace is always sufficient.

We begin by stepping into a time machine that takes us back a decade to the dawn of one of the biggest insights in the history of modern medicine.

For five decades before 2013, the community of scientists and doctors who help to treat people with cancer had dreamed of harnessing the body’s own immune system to identify and annihilate cancer cells. Research before that time had proceeded in fits and starts. It was clear that the immune system could sometimes recognize and annihilate cancer cells. But even patients with functioning immune systems would frequently develop cancers that would wreak havoc as only cancer can.

The year 2013 saw perhaps the only instance of before-and-after PET scans appearing on the front page of the New York Times. The accompanying article told one of the most exciting stories in the history of oncology. Before that time, if melanoma (the most deadly form of skin cancer) spread beyond its origin in the layers of the skin, medical oncologists had been almost entirely powerless to do anything about it. The single treatment option for patients was a drug that rarely worked and was thought of as “death in an IV bag” because of the terrible side effects it almost invariably caused.

While the immune system is very good at identifying and attacking melanoma cells, melanoma often invades the immune system by donning a type of molecular disguise. Metastatic melanoma cells had a system for evading detection.

The key therapeutic insight came when researchers developed a monoclonal antibody that would strip malignant melanoma cells of their disguise. In effect, this new drug tore off the molecular mask that melanoma had created for itself, opening those malignant cells up to the entire molecular fury of the human immune system. In initial trials, the effects of these drugs in the bodies of many patients who had malignant melanoma was so stark and profound that even a jaded oncologist feels obligated to reach for a word like “miraculous“ to describe their effects.

Patients whose bodies were entirely riddled with cancer spots would undergo just a few months of treatment and then find that no trace of cancer remained. Something like 70 or 80% of patients responded to the drugs, and somewhere between a quarter and a third of the patients saw their cancers not only respond but disappear entirely. In the course of a single trial, a disease that had been untreatable became, in about a third of cases, immediately curable.

And yet there is one physiological truth that every medical oncologist knows: There is no free lunch. No one expected as much from traditional chemo drugs, which amount to little more than carefully controlled poison. Indeed, one drug given for a common type of lymphoma is the active agent in mustard gas. In terms of side effects from these new immunotherapy drugs, it soon became clear that when these therapies go awry, the consequences largely mimic what we would expect: An immune system supercharged to fight cancer cells can also attack any part of the healthy human body.

A few years ago, I admitted to the hospital a patient who had been started on a particularly potent form of immunotherapy. His cancer had developed slowly, but he and his oncologist had decided that it made sense to try to get ahead of the game, hoping to drive the cancer into something like complete remission. Some months after starting the therapy, however, the patient began to have abdominal pain and bleeding. A complex battery of tests eventually showed that his immune system was aggressively attacking his intestines. During an emergency surgery late one night, his entire large intestine was removed. It was initially hoped that this would rid the immune system of its immediate target. Instead, even after the surgery, it was as if the immune system was an angry god that had been awakened and perturbed by insolent and meddling medical professionals. Within a matter of hours, his immune system began to attack his lungs and his heart, and then his entire physiology began to fail. In the day or so after the surgery, his immune system whipped itself into a terrible frenzy and his white blood cells effectively attacked every part of his body. The very system that was meant to protect his life had caused his death.

This harm caused in the name of defense has seemed strangely relevant in recent months as I have read a spate of both historical and contemporary treatments that examine the course of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. These recent readings have included sources as disparate as Benjamin Park’s new biography of the Church, American Zion; Terryl Givens’ biography of the irrepressible Church intellectual, Eugene England; and the recent difficulties at Brigham Young University concerning who should be hired, what should be taught, and how the university should be administered.

What unites these varied stories is that all of them are marked by significant conflict—battles fought sometimes in public and sometimes in the lonely foxholes of the heart. But, whatever the details, these stories matter a lot to me as a Church member. Indeed, I suspect most of us come to these stories with our own sympathies predetermined, and we may leave them with fixed ideas about which figures are heroes and which are villains. Yet I think there is another way to approach these tales—a way suggested to me by my understanding of the body’s immune system.

In explicating the New Testament metaphor of the body of Christ, Paul emphasizes that each part of the body is irreplaceable, and it would be absurd to try to rank them in hierarchical importance. As he says, one part of the body cannot say to another part of the body, “I have no need of thee” (1 Corinthians 12:21). Such arrogance would invite danger and folly.

This all seems to make good sense to us, in part because we most often imagine the body to be a symphony of beautiful synchronicity. In many cases, this is precisely true. The heart, after all, is responsible for delivering blood to the lungs, where it can be oxygenated. Then, the heart is likewise responsible for providing the forward motion that ferries that blood, now carrying that life-giving oxygen, to the other parts of the body. Thus, the efficacy of the lungs’ never-ending ability to scavenge oxygen from the air depends entirely on the heart doing what it does without fail. Even if the lungs maintained their ability to allow oxygen into the interior of the body, that ability would be useless if the heart were to stop pumping.

At the same time, however, even if the heart kept pumping blood through the body, if the lungs were to stop making oxygen molecules available, blood traveling everywhere in the body would do no good if it carried no oxygen to the other organs, all of which are desperate for the arrival of oxygen every moment of every day. Simply put, the heart and the lungs need each other. If either of them ceases to function, then the body will die within moments. Though it might take a little more time, the same is true if the liver, or the kidneys, or the intestines, or even the skin begin to fail.

But then, we arrive at the curious case of the immune system. Where virtually every other part of the body is meant to deliver life, to mend, to sustain, and to heal, the immune system is something quite different. The purpose of the immune system is to identify targets that need to be eliminated and then to proceed with the process of annihilation. In this way, the immune system is singular in all of the body. People born without a functioning immune system cannot live. But it turns out that the immune system is even stranger than that. Not only does it differentiate itself from the rest of the body by its lethal intent and effect (lethal, anyway, to bacteria and other invading organisms) but also because of this key fact: The immune system is forever arrayed against itself. Whereas some parts of the immune system are meant to eradicate bad cells, other parts of the immune system exist entirely to hamper the function those initial immune cells are meant to carry out.

Because this is the case, the immune system is divided into parts that exist in delicate tension and balance with each other. In this way, the different parts of the immune system function rather like the pedals of a car, with both a brake and an accelerator. Without the former, the car would inevitably crash, but, without the latter, it would never move at all. Similarly, without the cytotoxic (that is, “deadly to cells”) element of the immune system, the body is left defenseless—vulnerable to every threat from without and within. Without the second part of the immune system (the “regulatory” component), however, every common cold, bacterial infection, or allergy would elicit an overwhelming inflammatory response that could, in and of itself, be fatal.

When I consider these forces whose very nature requires them to be constantly held in tension with each other, and consider this tension in the context of Paul’s reminders about the importance of every element of the body of Christ, my understanding of the metaphor changes in an important way. The normal understanding I bring to Paul’s metaphor would suggest that every part of the body of Christ should be working in obvious synchronicity with every other part. We do not, after all, usually think of the lungs as being at war with the heart, or the liver in a battle with the kidneys. But in the case of the different arms of the immune system, we are presented with parts of our inherent and normal physiology that exist precisely to keep each other in balance. These arms of our physiological function must be in tension with each other in order to keep the body orderly and functioning. This is a curious case because, on the one hand, if the immune system is sluggish or inactive, as with melanoma before the advent of immunotherapy, then disease can run rampant or cancer can grow. Yet, if the immune system becomes activated without control or regulation, then a patient can die in a flurry of immune activation. Both the attacking and the regulating arms of the immune system must be intact and active—and both must keep each other in check forever.

I believe this is also true in the body of Christ.

In Terryl Givens’s Stretching the Heavens, for example, we read of how Eugene England approached his place in the Church with what can only be described as childlike innocence, enthusiasm, and guilelessness. At times, this earnestness bordered on naivete. But what is unquestionably true is that Brother England believed deeply in the sanctity and divinity of the Church and wanted desperately to make it more like the heavenly kingdom on earth he fully believed that it could be. It is striking, then, that for all his earnestness and devoted discipleship, he found himself almost constantly at war with the representatives of the institutional Church, whether with his dean and other leaders at Brigham Young University or with the apostles with whom he so often and openly corresponded. Indeed, in this era of increased transparency about Church history, and largely because of the writings of Eugene England, Kristine Haglund, Joseph Spencer, and others, the battles between Elder Bruce R. McConkie and Eugene England have now become the stuff of legend.

But what is also true is that this battle between two well-meaning and deeply devoted Church members is in no way unique. In American Zion: A New History of Mormonism, historian Benjamin Park shows that these internal battles have been a defining feature of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints since its inception. We, like most people in any organization, like to understand our history as linear and tidy. But what Dr. Park shows unmistakably is that the history is actually anything but. At every important juncture during the Church’s nearly two centuries of existence, there have been well-meaning, dedicated, and devoted disciples arrayed on various sides of complex and deeply sensitive issues. In virtually every case, those involved in any of these difficult questions are trying with their whole souls to advance what they understand to be the good of the Church and its members. Likewise, recent years have seen simmering conflicts at and about Brigham Young University as the institution grapples with what it means to be a religious university in an increasingly secular world.

In reading these accounts, I tend to instinctively sympathize with one side or the other in the various debates. For example, some people will look at the story of Eugene England and see him as a brave voice in the wilderness, speaking truth to power and raising ideas that, though novel and unpopular at the time he articulated them, have mostly been embraced by the institutional Church decades after his passing. Others might read the same story and see in Brother England a self-assured iconoclast who was more interested in the promotion of his own ideas, whatever the cost, than he was in working within the defined parameters of the institutional Church to advance the building of the kingdom of God on the earth. According to our own backstory, experiences, and intellectual attitudes, most of us will want to incline toward one or the other “side.”

Yet, Paul’s metaphor of the body of Christ, along with the physiology of the human immune system, suggest to us a more demanding and capacious approach to the stories. Though it’s comfortable to accept one or the other of the characters or perspectives, what is important is recognizing the beauty and necessity of both of the forces that are constantly held in tension. That is to say: If I am inclined to lionize Eugene England at the expense of seeing the value in the institutional Church, Paul’s metaphor coupled with this understanding of the immune system suggest instead that I need to recognize that all arms of the immune system matter, even as the various arms push back against each other, working at apparent cross purposes. In the body of a human, without the balance between the countervailing arms of the immune system, one of them would run rampant and could become dangerous or fatal. Yet if I am inclined to cheer for the institutional Church while shaking my head in disbelief at the antics of a self-described “liberal egg-head professor,” this metaphor invites me to reconsider my position and allow for the possibility that the Eugene Englands of the Church are just as important as the arms of the immune system that keep all the other elements from introducing excesses that would be dangerous or fatal.

It is also essential to be clear about a few limitations of the metaphor. In suggesting the beauty and necessity of those working on many or all sides of the various debates—large and small—that have defined the Church’s history, I do not mean to suggest symmetry, let alone equality, in every case. Certainly, at least insofar as impact and influence within the institutional Church is concerned, those who represent that institution will always have something of an upper hand. Any lone voice in the wilderness, a la Brother England, will see a limit to the scope of her or his impact that differs from that of a representative of the institutional Church. But even recognizing such asymmetry does not negate the power of the metaphor because the history of the Church nonetheless suggests that the Eugene Englands, Minerva Teicherts, Juanita Brookses, Carol Lynn Pearsons, and all the rest have often had impacts that belie the apparent size of their initial reach.

Furthermore, none of this is meant to suggest that there are not times when some part of the body of Christ can become truly diseased—those times certainly exist, and identifying and responding to them is deeply important. After all, cancer is still cancer and bacteria are still bacteria. The very existence of an immune system reminds us that we need that immune force precisely because there are moments when a genuinely malignant entity must be destroyed. But recognizing these parts of the immune system that lie forever in tension with each other nonetheless opens a space for us to see that even entities within the Church that appear to be at odds may both be necessary and moving toward the same end.

I am not arguing here about the right-ness or salutary nature of any particular person, episode, or action—even those mentioned above. Ultimately, the eternal goodness or lack thereof is something I believe no mortal can judge. The keeper of the gate, after all, is the Holy One of Israel, and he employeth no servant there. I point out this aspect of the immune system only to create a space that I believe to be both historically important and spiritually vital. The historical importance comes when we recognize that sussing out who was “right” and who was “wrong” is often much harder than we suppose, especially because we are so prone to sympathize with one side of a debate—and to believe that that sympathy somehow necessitates demonizing, or at least dismissing, the “other side.” History is always understood through a series of impossibly complex prisms, and none of us can strip those entirely away. Even if we somehow could, none of us can be rid of our own biases, prejudices, histories, points of view, and burning questions. Our interpretations of history—and the imagined sympathies and allegiances we form as we consider historical questions together—will forever be colored by these experiences and points of view.

The expanded view this essay advocates invites us to read Church history with a charity that can apply equally to all well-meaning parties, no matter where they fall in the institution, and no matter on which side they find themselves with respect to any given debate. This seems to me to be something akin to what Moroni pleads with us to bring to The Book of Mormon when he writes, with pathos and anxiety: “Condemn me not because of my imperfection, neither my father, because of his imperfection, neither them who have written before him; but rather given thanks unto God that he hath made manifest unto you our imperfections, that ye may be more wise than we have been” (Mormon 9:31). The reading of history can also become an act of charity.

Beyond this, understanding this relatively obscure facet of the immune system matters because it endows us with a meaningful new dimension of discipleship by opening our minds and hearts to the possibility that divinity lurks behind even persons and actions that seem inherently opposed to one another. Melissa Inouye once puckishly observed that “Jesus said . . . love your enemies—[what] better place to find enemies than in your local ward.” Likewise, Kristine Haglund has ruminated on the “rough seas” we must unavoidably sail as members of “a Church dedicated to preserving maximum freedom of individual conscience and agency while still needing to create enough shared belief to cohere.” And I believe both of these get it just right, while reminding us of a truth that all Church members learn quickly and well: At Church, we will find both institutional strictures and individual personalities that seem at best deeply frustrating and, at worst, genuinely opposed to our understanding of how the kingdom of God is supposed to be.

But in the arena of pursuing personal discipleship in such a kingdom, the character and functioning of the immune system matter a great deal. I recognize the importance and rightness of elements held forever in tension, which allows me to pursue building the kingdom with earnest forthrightness while still giving me capacity to believe that someone who does so—but does so very differently—might also be in the right. We may both be simultaneously about the Lord’s errand, even though we seem to be pursuing either the same work in different ways, or even different works entirely. This expanded view of who can claim the mantle of inspiration when working within the body of Christ thus freights us with a burdensome element of our discipleship: We really are meant to pray not only for those who seem to be opposed to us, but also to see more fully where they are coming from. Making peace within the Church is not a matter of grudgingly managing to bear the presence of someone with whom we disagree but of actively seeking to better understand why they think and feel as they do in order that we can attempt reconciliation.

As I have made this effort to ponder either my own various challenges or to consider the workings of the individuals I read about in Church history, I have too often found myself desperately wanting to know, in an echo of Joseph Smith’s initial plea: “Which of them is right?” Or, put slightly differently, “Which of them is inspired by God?”

But one night recently, as I contemplated this very question, an insight came to me like lightning: “What if the answer is ‘all of them’?” And in a way I have difficulty describing, this idea feels deeply true. Obviously, I am unable to discern who is right or wrong or what is the right strategy or approach to any or all of these questions in any ultimate sense. But still, the understanding that seemed to come to me that night was something like “God is bigger than all of this—God can inspire, variously, even the people who think they are arrayed against each other. God’s view is large enough to value and inspire both the loyalty of the institutionalist and the compassion of the gadfly, the meekness of the peacemaker and the passion of the firebrand.”

I believe God can be found in all of it.

Tyler Johnson is a medical oncologist and associate editor at Wayfare. To receive each new Tyler Johnson column by email, first subscribe to Wayfare and then click here to manage your subscription and turn on notifications for On the Road to Jericho.

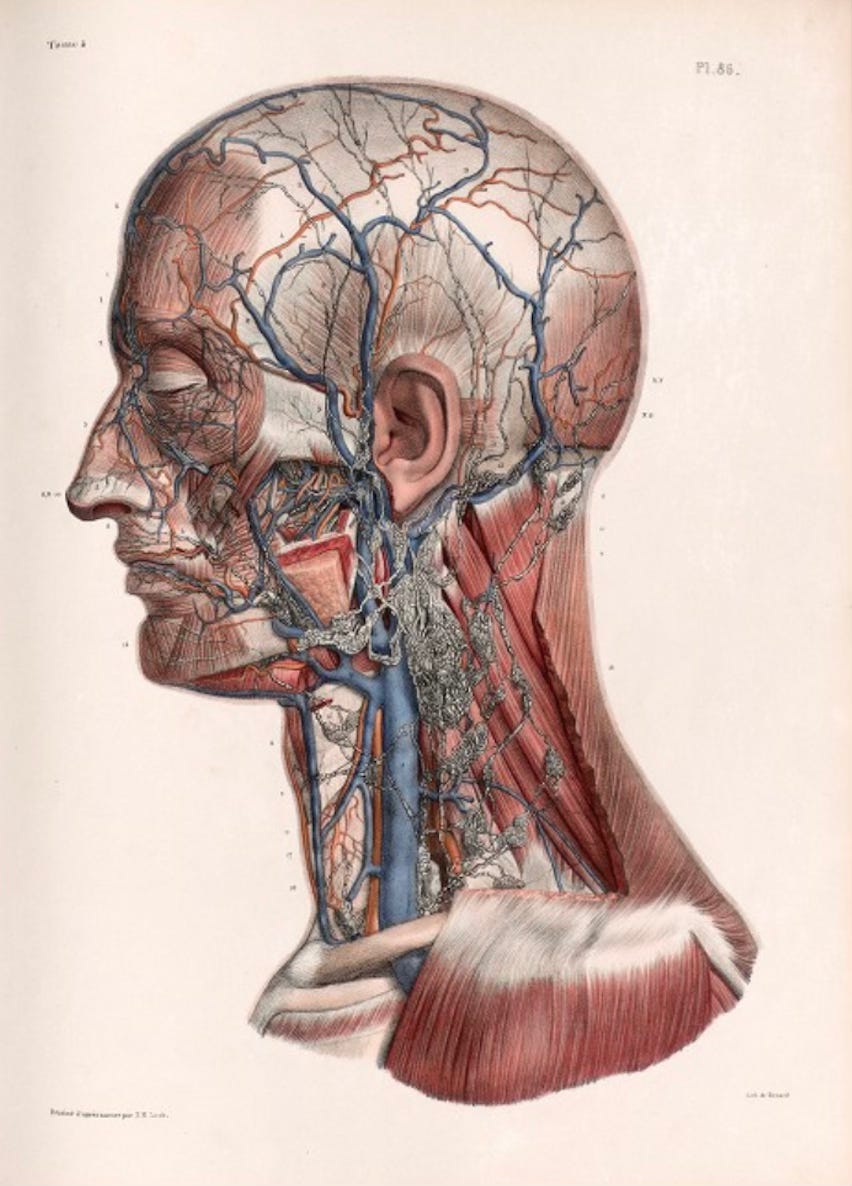

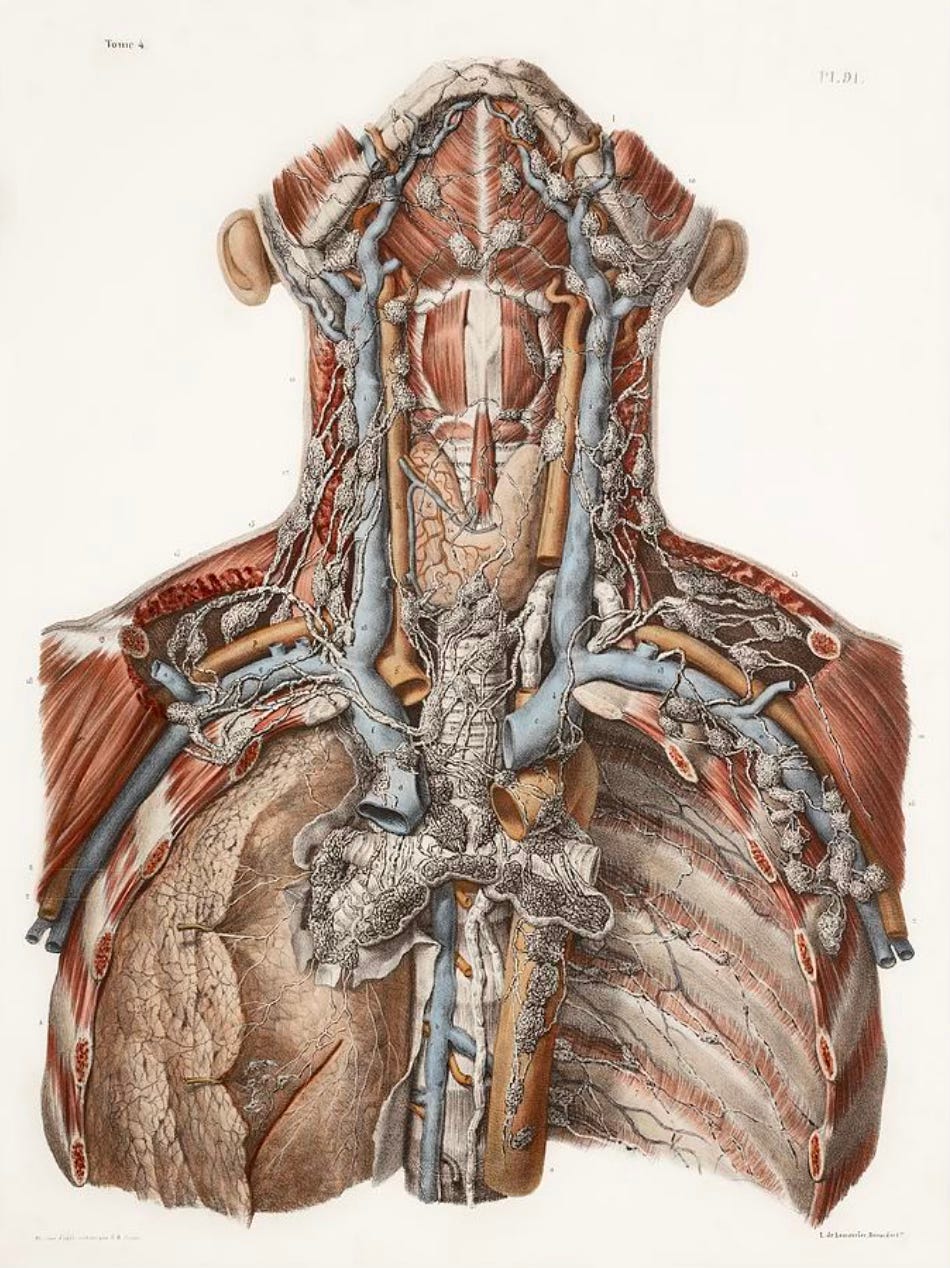

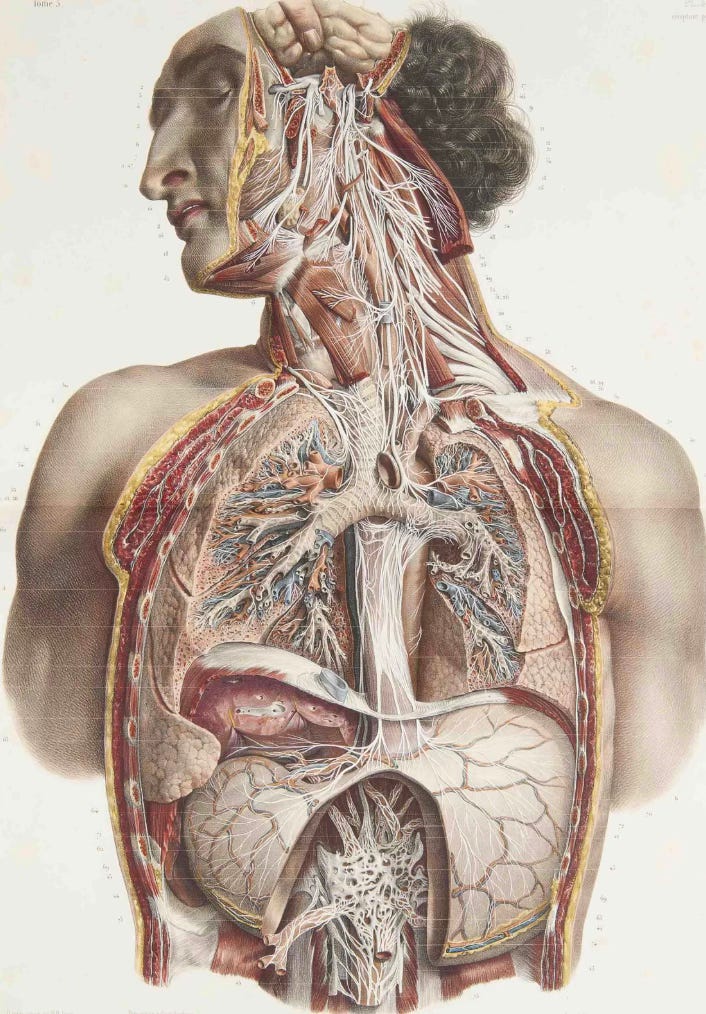

Art from Traité complet de l’anatomie de l’homme (1831–1854). Illustrations by Nicolas-Henri Jacob (1782–1871).