Ghosts in the Church Parking Lot

On Paths Not Taken

One long yawn. After his yawn, the tired toddler threw a toy car and babbled with newfound ire. My twin sister seized him from the floor and announced, “You’re ready for bed!”

I knew what this meant: My presence in the room had flicked like a light switch from pleasant to inconvenient, though my sister would never say so. I was visiting Utah from Washington DC, and as is the case with every visit, those transitional minutes between day and night reminded me that I was indeed a visitor—if a beloved one. Born within minutes of each other, raised barely an arm’s length apart, our lives had forked in different directions.

Time to disappear.

I stepped outside for a walk around her neighborhood in West Provo. Pulling out my phone, I opened my podcast app for something to listen to. A white box with black lettering appeared, a ghost of an old dream. It was On Being with Krista Tippett, a podcast I hungrily consumed about a decade ago, around the time when the fissure first began.

In college, my twin sister and I began to seriously worry what it would mean for our futures if we remained Mormon. Could we be honest in this faith? Could we marry and raise children within it? As roommates in a corner apartment of the old Heritage Halls, we took turns disappearing into our walk-in closet to pray. Over time, I made a rugged peace with the questions. My sister did not.

Professors had helped me envision appealing ways to continue in the faith. Friends introduced me to media I had never heard of, including the On Being podcast. Krista Tippett struck me as a type of woman I could aspire to be like: thoughtful, empathetic, unmarried yet respected, the indubitable mother of a global family that she summoned under her wing. Her interviews with artists, philosophers, faith leaders, and scientists on what it means to be human glimmered like the words of Joseph Smith: “We should gather all the good and true principles of the world and treasure them up, or we shall not come out true Mormons.”

My sister was closer to our older siblings, who had grown disenchanted with the faith we inherited. They were wary of how the Church fumbled in responding to the vulnerable, and of how it made little space for dissent. They listened to Mormon Stories with John Dehlin and fearlessly enjoyed the Book of Mormon musical when it came out. My sister’s boyfriend, a person of dogged integrity, experienced religion as a constraint on his honesty and sense of wonder. With him, my sister saw another type of future: one where life’s joys and sorrows and the mysteries of the universe might be lovingly held within intimate family relationships.

I cried when she got double piercings in her ears, not because I believed it was sinful, but because I felt she had left me alone. She attempted to hide her tears from me when I chose to go on a mission, afraid she would lose me forever. Yet the symmetry of our fears wasn’t lost on us; an odd and gentle understanding still lingered, reminding us we still belonged to time, to space, to history, and to each other. We shared a world, even if, like the earth at the beginning of Genesis, it felt suddenly formless and inchoate, waiting for the Spirit of God to move upon it.

We rarely spoke of our differences directly, sensing that it wasn’t time yet, that words would disturb the dark and peaceful waters between us. We found other ways to remind each other, knowing this peace could easily slip out of view. We kept our inside jokes, the spoils of a shared history. We let ourselves be silly together, setting aside our working theories of society and ethics to simply play. We brought each other gifts—mint brownies from the Creamery, blueberry muffin top cookies from Provo Bakery—to show our mutual fondness.

An ironic ritual developed between us: the sister who had bought the cookie would take a hearty bite before placing it back in the brown paper bag to deliver to the other. While anyone else would think it tasteless and rude, this ritual showed we were safe to be uncareful around each other, to indulge a whim or selfish impulse. These were gifts from one goofy sister to another, not formal offerings exchanged between faction leaders. Our ritual also celebrated the surprises of life and our own close entanglement: One sister thought she would receive a whole cookie, and instead it was mostly whole with a crescent bit into its surface, anointed by her sister’s spit.

The podcast episode began as I started my walk. In my earphones, Krista Tippett introduced her guest for that day and invited me to “drop into this conversation and gather refreshment for life in this world.” What world? I quietly pondered. Was there anything more she would say about it? Her introductory sentences felt like ghost towns, uninhabited by detail, gesturing at a world we shared in common but saying little to invoke it.

I made a different bargain with time than my sister did. Over the past decade, I took opportunities that loosely followed Tippett’s path. I moved across the country, went to graduate school, and let my circle of friends grow wider and wider. I pursued jobs that I imagined might usher in a world of jubilant spiritual pluralism modeled by On Being. I dated in and outside of my faith and met people from all over the world, although I never married. Yet the more expansive my world became, the harder it was to identify where I was or who was with me in it.

My colleagues and I talked a lot about family, the importance of it. Sometimes we even called each other “family.” But when the COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the transactional foundation of work-based relationships, I began to see the trade-offs I had made. Just months before, my workplace, dedicated to multifaith work at a university, had felt like a congress of world religions; now we received curt emails announcing triage decisions: Who would stay and who would go? Who would be temporarily furloughed?

Meanwhile, the moral demands for “diversity” jobs reached a feverish pitch, sometimes compromising the integrity of the work. Urgent calls for change drowned out gentler calls for understanding. As accusations rose, a counter-reaction exploded in the culture that mocked hopes for social change altogether. Fractures in the American public grew more and more transparent and I increasingly felt at a loss for words, knowing anything I might say could potentially harm people who needed love and respect.

Years floated by. At some point, I began to feel like a ghost in my own life.

I continued my walk around my sister’s neighborhood, passing driveways and front porches dunked in shadow, wondering which neighbors she did and didn’t know. I tried to imagine the memories my nephew would carry with him of this neighborhood, maybe of games at the nearby swimming pool, fights in the nearby park. His life, and my sister’s life, had a durable quality I could only hope mine had as well. Despite the dissonance she felt with Mormonism, and despite my defense of it, it was my sister who made her home in the Mormon-saturated region where we were raised.

I paused in an empty parking lot of a Latter-day Saint chapel. This was where my sister would attend, were she churchgoing. I had not visited this one before, but felt I might as well have for how much time I’ve spent in nearly identical chapels. I could imagine countless families like ours that had driven across the tar-striped asphalt on Sunday mornings, and all the contours of their conversations. The building felt inhabited, even while lying vacant in the dark. My sister would sense this, were she here, not putting her son to sleep. We shared countless memories of sacrament meeting talks and youth activities. Having lived side by side for the first two decades of life, we knew each other’s friends, boyfriends, rivals, and mentors, the dreams both achieved and unrealized. Now, as adults living miles apart, we intimately know each other’s ghosts.

Last we talked about it, she was considering going back. Certain anxieties she thought might be resolved by leaving never actually went away. Her evaluation of the Church has grown complex as she’s learned that people outside it rarely live up to their standards, either. And now she is looking out for a future generation. She worries what it will mean for my nephew if he never learns the spiritual language of his family and of Utah’s surrounding culture. What if he never hears the scripture stories that his grandparents speak of so often? What if he feels like a fool around friends’ families who pray, not knowing how to fold his arms? What if he wants to pray, someday? Would she be restricting his freedom, by not teaching him to pray? After all these years, she’ll admit, she still finds herself praying: on planes when the turbulence grows intense, in the middle of marital fights. Some of the teachings, she’ll confess, might be true.

Many years ago, while studying together in the university library, my sister and I began arguing in hushed tones over how to interpret a recent talk from a Church leader. To her, the talk was obviously bigoted. I thought it wasn’t so obvious. “You’re doing mental gymnastics,” she insisted. “You won’t read a single article about this topic,” I snapped. As the argument reached its peak, and hurt emotions rose, we looked at each other and glimpsed how something sacred would be destroyed if we continued like this. The view of my own complicity surprised me, since it was my sister who was abandoning our faith. We dropped the topic and broke into reassurances. “I love and respect you. I’m sorry for making you feel like I didn’t,” we both said.

The world we shared was something we hardly understood, and the cost of preserving it might very well be our ability to speak clearly about it, at least in that moment. We would retreat into darkness, tolerate being misunderstood, establish what rudimentary rituals we could to hold on to each other, and let time play its role in the rearticulation of our world.

Now, for example, we can talk about religion. We can debate detailed points productively. Like God did as he spoke the world into existence, we have learned to gather and divide elements simultaneously. Still, we sometimes find ourselves stepping on something tender, and have to pull back and lean into that formless expanse, all the parts of shared life that words can never capture—the jokes, the history, the memories, the silliness, the constant upheaval of plans.

We recently had an argument while visiting our parents in our childhood home. She was tending to her son; I was doing my make-up, getting ready to meet a friend. She was ruminating out loud over whether to take her son to church; she wanted an expansive life for him, and worried about its insular, homogenous culture. I suggested that the culture wasn’t so bad, and besides, sometimes the thickest walls of human diversity are between people in close proximity to us. As the conversation developed, she found me invalidating while I found her closed-minded. (We didn’t catch the irony that the other was living out our arguments better than we were.)

When we reconciled this time, we found tepid words to dignify the other’s life. “I know you want to be brutally honest with yourself,” I said to her, “And you’re willing to bear the cost of that, even if it means taking things the hard way.” She said to me, “I know you want to build a better world that doesn’t exist yet, and you have taken a lot of risks to try.” These are not the final words we have to describe each other; we are still evolving, still aware of all we can’t see. We know, most of all, that it is a gift to be together as the world continually re-creates itself.

Diana Brown, civil society entrepreneur in Washington DC, co-hosts The Soloists podcast and directs the partnership between the One America Movement and Faith Matters.

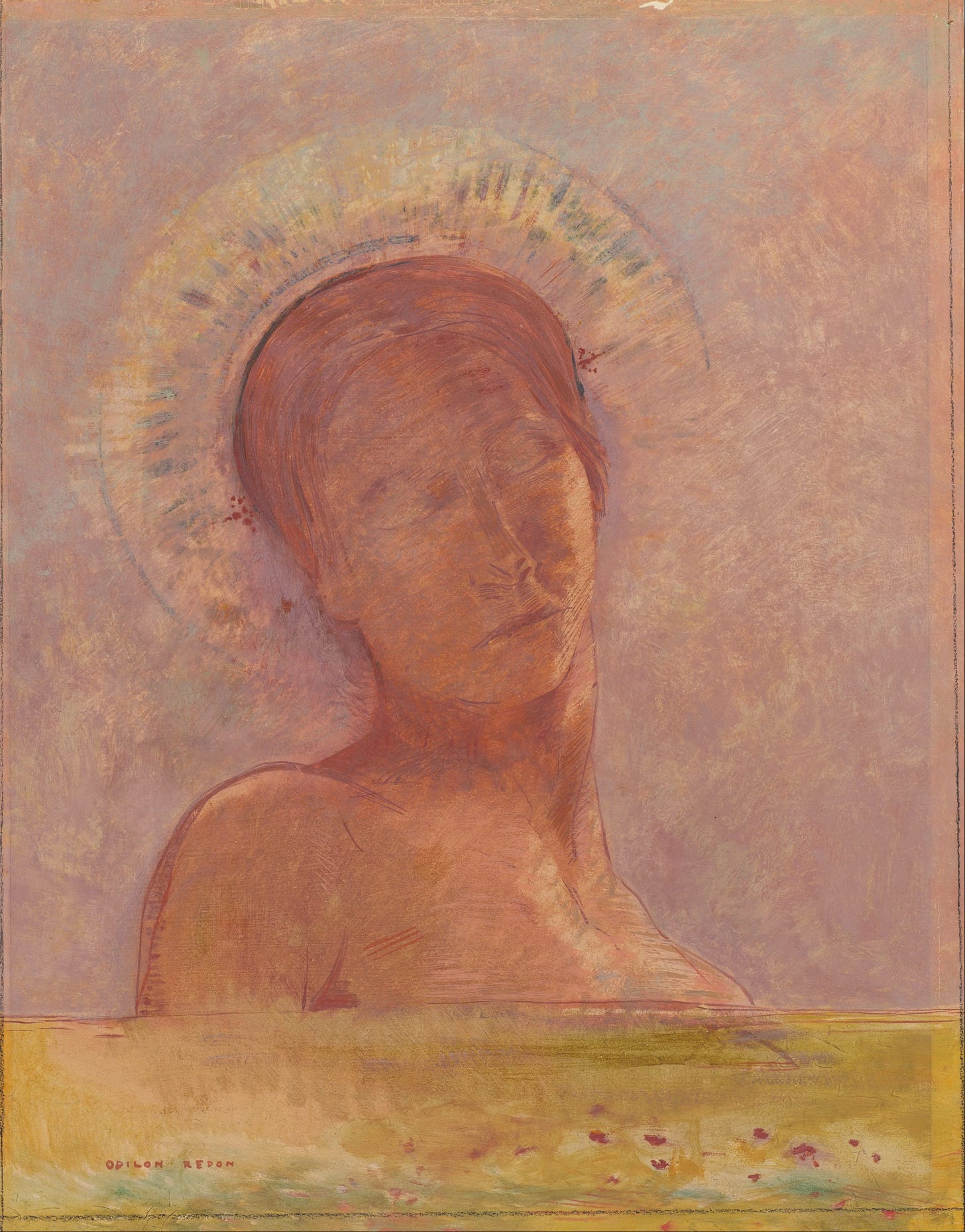

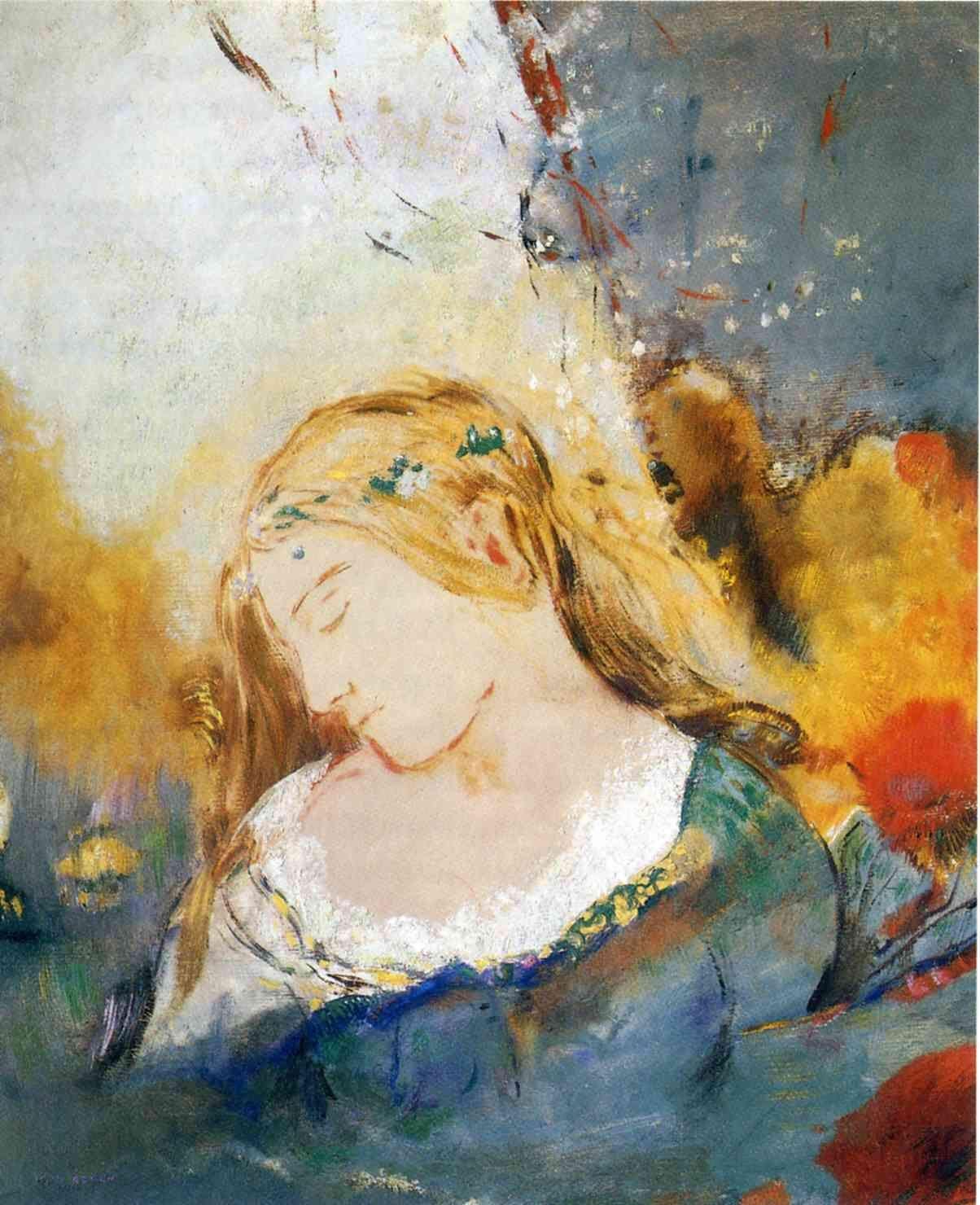

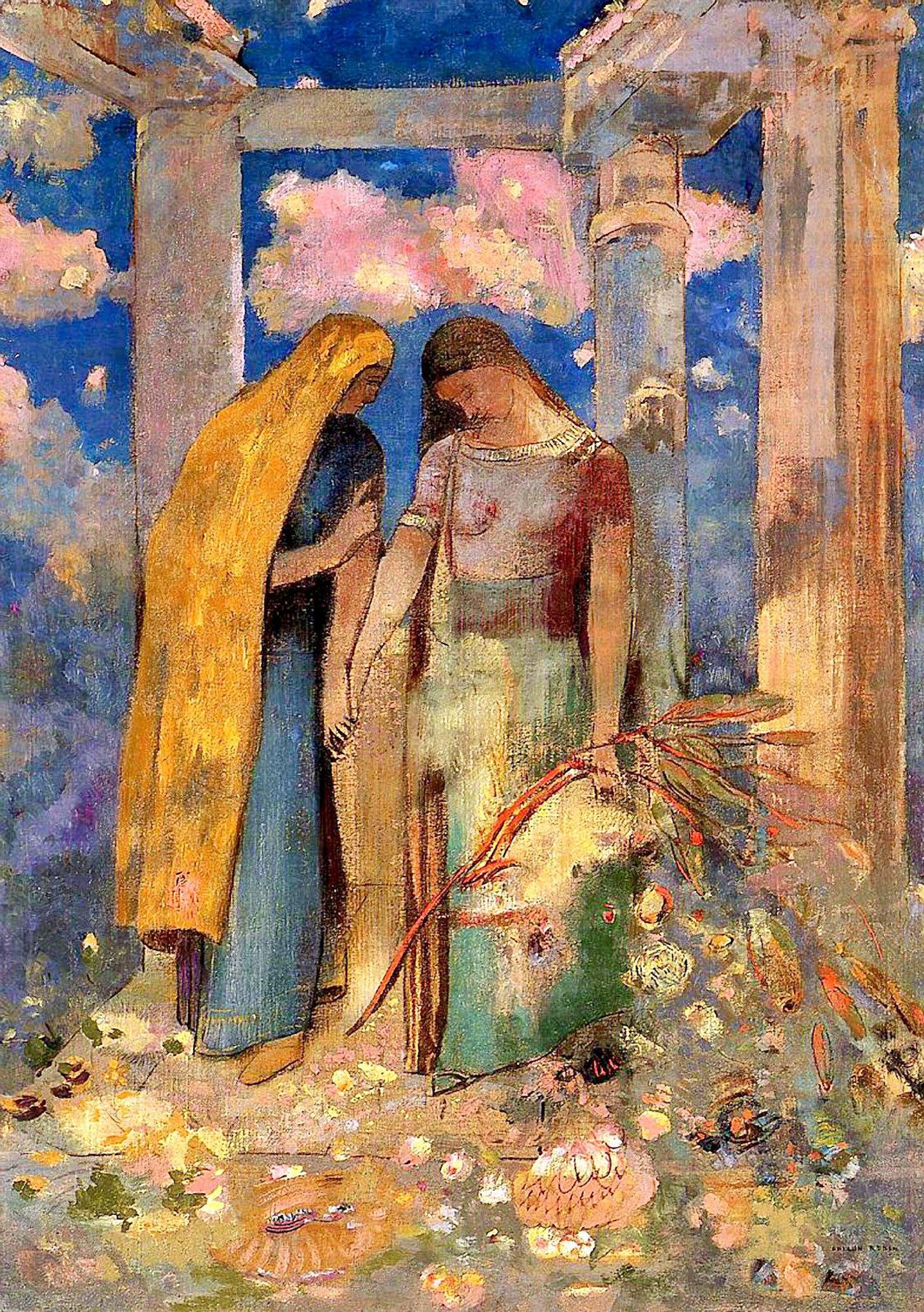

Art by Odilon Redon.