From This Tree Grows the Crown

"Everything that originated from the Tree of Knowledge carries in it duality." —The Zohar, mystical Jewish text

“Thus love is oftentimes represented by the pomegranate, which . . . may be said to be the virtue of this tree; . . . it seems to be its gift, which it offers to man by love; . . . its glory and beatitude, since it bears the crown and diadem.” —Saint Francis of Sales (1567–1622), Treatise on the Love of God.

A being of brilliant light offered her the fruit. Eve knew this fruit and the tree it came from. She had longed to understand why this tree called to her. She knew it was forbidden—because of death. The seraph spoke. He said he was her brother. His words began to unravel the riddle of her connection to this tree. He said this tree’s fruit gave knowledge of good and evil. She knew this, but it wasn’t until the seraph’s tongue hissed truths deep and eternal that she began to understand. The being of light explained that knowledge only came from contrast: pleasure and pain, sickness and health, joy and sadness. As he spoke, Wisdom opened the eyes of Eve’s understanding. In the Garden, there was only light, ease, and beauty. She could not progress here. She had to pass through sorrow to gain wisdom. She had to experience exile to know paradise.

Duality is the door.

Pleasure and pain. Health and sickness. . . . Life and death.

At last, Eve saw the connection, her connection, to the tree. To bring life into this world—to fulfill the measure of her creation, to be the Mother of all Living—she also had to bring death.

One required the other.

Looking toward the Tree of Life, she asked tremblingly, “Is there no other way?” Behind her, the serpent hissed, “There is no other way.” Eve didn’t understand exile, or death, or sacrifice, but she rose with courage and hope and, trusting her brother, extended her hand and said,

“Then, I will partake.”

I was twenty-one when God reached out, trying to get my attention. At first, it was subtle, like the scent from a budding tree. When I first got a hint of what he was saying, I pretended I hadn’t heard. It was easy to do. He spoke a little louder when the organ played at church, and I bowed my head and opened my heart, but when I heard his invitation again, clearer this time, my head shot up, and my eyes opened wide. After that, I avoided God. I had heard what he had to say and wasn’t ready to talk. I needed time.

So, I said quick, empty prayers for weeks. At one point, I stopped praying altogether. Whenever I closed my eyes and opened my heart, there he was, holding the question I didn’t want to answer. If I could have jumped on a ship and sailed to Tarshish, I probably would have, but I knew enough about the story of Jonah to know how well that turned out.

You can’t run away from God.

I told no one about my soft rebellion, not even my husband. One day, I realized God was quiet. The knocking had grown distant. Had he given up? Ironically, it was his retreat that turned me around. His words had planted a seed I needed to uproot or leave to grow. It was time.

As I readied myself for the showdown, I decided to fast. I needed spiritual strength and mental focus to wrestle with God. After twenty-four hours, I told my husband I was going for a walk. I needed to be alone. I did all the talking at first, flinging at heaven all the questions I had kept bottled up till now. One after another. For miles:

Why?

What about school and my plans for graduate work?

I am young.

Why can’t it wait?

I will have children one day.

I want to be a mother.

Why does it have to be now?

What will people think? They’ll think it was an accident.

Everyone says it’s better to wait a couple of years, even the experts.

How can this be your plan?

What about my plans? Don’t they matter?

After a while, it all boiled down to one question:

Why now?

Tears were building as I looked up at heaven, frustrated and confused. I needed answers. I needed wisdom.

Then, through the tumult and strife, I heard

A still, small voice.

It pierced me to the core. God had asked me a simple question:

Are you going to let me guide your life, or are you?

There was no judgment. No shame. In fact, it felt like an invitation. I considered logically what I knew about God that would persuade me to let him be my guide. First, I knew God was omniscient. He could see further than I could see. Second, I knew God loved me. And, as part of that love, I knew he wouldn’t ask me to do something that wouldn’t bring me ultimate happiness.

My mind and heart repeated those two basic facts: He knew more than me, and he loved me. Those were two strong reasons to let God guide my life.

But I mourned what I would be giving up. Choosing to be a mother now would derail all my plans. My life would never be my own again. I wasn’t ready and didn’t know how to be a mother.

It seemed heaven held its breath as I weighed the costs. It was one of the few times I felt the reality of faith. I held it in my hands. I took a deep breath, fixed my eyes on the tops of the mountains less than a mile away, imagined myself on top, near heaven, and yielded. It is the best word to describe what I felt. I yielded my will, my plans, my timing to his. I said out loud:

Okay. I will allow you to guide my life.

It was over. It was beginning.

I chose to be a mother.

Two months later, I was pregnant.

“It’s time to push.” She didn’t need to tell me. My body was screaming to bear down; sinew and muscles were moving there with or without my consent. It was primal, instinctive, a knowledge buried deep, passed down from mother to daughter from the beginning of time, unknown and unknowable until—“Now.”

Strangely, as I surrendered, I was empowered. For hours, I had been concentrating on staying in control, managing each wave of pain with breath and focus. But now, it was time to harness the pain, to use its ancient power to part a veil. With each contraction, I pushed with might and soul—pain and woman working in unison. As the veil began to part, I felt fire for the first time inside me. I feared the fire would tear me open—consume me, and it did. Creation demands blood, and mine spilled to the floor to open this doorway; mortality hinges on sacrifice.

“She’s crowning.” I felt the words before I heard them. I laid every fiber of my being on the altar of life. I cried out into the vast expanse of mothers before me, adding my pain to theirs; they held me, though I knew it not. All dross consumed as I pushed into the flames instead of pulling back. And then: it is finished.

Crowned with flesh, my daughter emerged full of glory, light, and life. Her cries filled the room like angel choirs. I lay back, exhausted and complete. Tears rolled down the sides of my face, pooling in my ears, but I heard her just as clearly as I heard heaven accept my offering and crown me eternity’s highest title: Mother.

They laid her on my breasts. Her tiny heartbeat and rising and falling chest pressed against my own. What was one had become two. Dad cut the cord, but nothing could break the bond between life and life-giver. I knew this instinctively, powerfully. Her dark eyes took me in; she stopped crying. I saw majesty for the first time and wondered at the miracle of her perfection and the lowly handmaid God had entrusted with such a gift as her. I laughed and cried tears of joy. All pain swallowed up in purest love. Fire becoming glory.

Mothers need mentors. My own mother was too tired to mentor much. She was widowed at forty-two, and by the time my babies came along, the last thing she wanted was another baby placed in her arms. When I asked her questions: “How do you get babies to sleep through the night?”

“Is it okay to nurse on demand?”

“When are they old enough to . . .?”

She often shrugged her shoulders and said, “I don’t know how I did it. I just did.”

My mother-in-law, Linda, was different. She had not been worn down by carrying the burden of a family alone. When my first baby would cry for no apparent reason, she never offered advice, only reprieve. The first time, she said, “She’s going to cry the same with me as with you, so let me take her for a bit.” She grabbed a blanket and walked out the front door. The silence was healing. I looked out the window and saw her holding my baby up close, bouncing her lightly. The way she swayed and walked, I was sure she was singing to her granddaughter.

After four months, I returned to school, determined to finish my undergraduate degree. Linda lived just a mile from the university and offered to watch my infant while I was in class. I never could have finished without her. For a year, she read books, pushed a stroller, built block towers, and bottle-fed my baby to sleep.

As my daughter got older, they often spent time in the garden, where Linda had the beautiful habit of walking barefoot, her long dark hair held back with a simple headband, her body half bent in the ready position to pick a weed or deadhead a stem. Even with her devotion to her garden, when her grandchildren visited, they had her full attention. They would babble to her about the things important to toddlers, and she seemed to comprehend it all. She read them books and showed them bugs. As an amateur geologist, she taught them about rocks, moss, and lichen, and allowed them to contribute to her impressive rock collection with the common stones they found in the dirt.

For years, I watched and learned. She taught me to talk to children face to face and listen attentively. She laughed easily, joked lightly, and never sought to be the center of attention. As I observed her through the years, I learned what grace looks like embodied. I witnessed the power of nurturing from a woman who knew how to mold living clay with love and wonder.

Years passed, and Linda grew old. Her dark hair turned grey and wispy. Her fingers curled from arthritis and years of pulling weeds and nurturing life. When my daughter, now grown, was married in late summer, Linda attended in a wheelchair and commented on the beautiful flowers that made up her bouquet. Her granddaughter bent down close for a photograph, which is still one of my favorites.

Over the next year, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s took more and more from her. She shook violently at times and slept for long stretches. Sometimes, I’d take her for walks in the gardens around her facility. She’d always brighten up when I pointed out a flower or blooming bush, but when she couldn’t recall the names of these old friends, she’d shake her head in frustration and ask, “What are we doing now? Where are we going?”

One day, I stopped in for a quick visit. As I helped Linda get up from a long nap, her shaking suddenly became more violent. I tried to hold her close to me and calm her down, but she kept shaking and throwing her head about. I reached to pull the help cord and get a nurse, but no one came. Then her eyes rolled back into her head, and her throat and jaw cinched tight. I called to my father-in-law, who lived with her in the care facility. Her face was white, her lips blue, and her skin cold. I tried to find a pulse but couldn’t.

The convulsions slowed, then stopped, except for the occasional spasm, like a child’s body shudders after a long cry. Her body fell limp. Surprisingly, instead of feeling grief, I felt calm as I held her fragile body. She was the child. I was the mother. I smoothed her hair and told her she was good. She was loved. That it was okay to go. I gently rocked her in my arms. Her husband, in his own wheelchair, drew close, his shoulders shaking as he wept, quietly saying more to himself, “It’s okay. Let her go. We knew this time would come.”

Holding her, watching him, I felt the moment's sacredness. Suddenly, she jerked back—gasping, fighting for air. I told Grandpa, “She’s breathing! She’s still with us.”

Help finally came. Linda clawed back from the precipice of death. She lived a few days more, which allowed time for her eight children and forty grandchildren to say goodbye and thank you.

When Linda finally did return home in the early hours on a Sunday morning, I’m sure she was barefoot, her long, dark curly hair blowing back as she stepped from her broken body with grace, ready to join the world of spirits and tend a new garden full of light and love.

On a summer day, two years after her wedding, my daughter pulled out a tiny onesie and smiled knowingly at me, waiting for the realization. She was pregnant! Tears of wonder and hope danced as we hugged and laughed. I was determined to help her graduate with her master’s degree, as Linda had helped me.

The tiny bump grew, and nine months passed quickly. Then, forty-eight hours after the first day of spring, her delivery announced itself with a gush of fluid. At the hospital, things didn’t go as planned. Before being rushed into an emergency C-section, she called: “Will you come?”

We raced to arrive. Speedwalking down sterile halls, we tried to outrun our fears, but I saw them in her husband’s eyes as we arrived on the scene. They were emerging from the operating room, and the doctor and nurses huddled behind a desk. Something had just happened or barely been averted. I couldn’t tell which, but I noticed they stopped talking when they saw us. The air was thick with adrenaline, exhaustion, and fatigue.

As we returned to their delivery room, I noticed my son-in-law was in shock. He sat down on a hospital chair and dropped his head into his hands. My daughter was half-conscious. He looked up with tears in his eyes. The baby was in the ICU. I glanced and saw fresh blood down the side of her bed, evidence of a rapid rescue we would soon learn about. My daughter was only concerned about the baby. “Go, check on her.” Her husband was conflicted between his wife's needs and those of his newborn daughter, but we were there to help carry his burden.

The men left. As I passed by the bed, I saw more of her blood across the sheets. I sat close to my daughter and held her hand, struggling to process everything, filled with questions. She was heavy with meds. She had labored for hours. I whispered words of comfort into the darkened room: “Just rest. Everything is fine now. Your baby is okay. You got her here. You did so well.”

She lay still, covered in blankets. The beeping monitors filled the silence; minutes passed, and then she spoke with her eyes closed. She told me what happened when her womb was opened and she felt the knife cut in, how she screamed out in pain, “I can feel you cutting me!” How her baby struggled to breathe—her lungs thick with meconium tar.

Those were all the details she had the strength to give. I was stunned by the torture she had endured to bring this child into the world. I sat quietly, weeping at the sacrifice required, the pure love manifested by this young mother. I wondered at the pain endured—the different fire she had to walk through to bring life into this world—the crowning work a mortal body can accomplish. I wondered at all women who shed life-giving blood each month, who sacrifice and nurture, who shepherd souls through life, who bear the burden of the crown. I wept in awe and reverence, wishing I could have been there to help her in her darkest moment.

Then, she spoke words I believed instantly:

“Mom. Grandma was there.

She was so close to me. I could smell her, feel her standing right next to me.”

She stopped, emotion and exhaustion overtaking her. Then she continued as tears slowly broke from her closed eyes, rolling down her cheek.

“And there were others, Mom.

There were so many in that room.

. . . There were so many.”

Eve has grown old. Her years of exile have taught her much. The tree’s fruit planted seeds that have yielded a great harvest. Her wisdom is unequaled, and her abundance is profound. She has become the Mother of all Living.

Upon the mount, where the altar stands—the same one Adam built with his hands after their expulsion, crying as he lifted each stone—Eve now sits and remembers. Here, she often weeps for the sons she once held, Cain and Abel, and the deaths that tore them each from her reach. Here, she looks toward Eden and smiles, remembering the son God filled her empty, aching arms with, healing a piece of her brokenness.

Seth. So much like his father! She wonders how mortals, like God, can create in their own image. Even now, she sees Adam in him, the youthful Adam who once took the blood-red pomegranate from her outstretched arms and chose her instead of paradise.

Her memories fade as a hush of reverence settles around her. Her body grows cold and heavy. It longs to return to the earth. Trembling, she fights against the pull to separate bone and spirit, but it is stronger than her. At last, she yields.

She had waited for this day, wondering how death would come to her when the Serpent first offered her the fruit. Now, she approaches the blood-red horizon, her spirit separating from limb and joint as the veil begins to tear; a searing fire surprises her, familiarity dawns, as she looks around and sees “the transcendent beauty of the gate through which the heirs of the kingdom must enter, which gate is circling flames of fire”(D&C 137:2). Astonished, she smiles as she realizes that death is not an end but a birth. Of this, she is sure. For this, she steps more confidently into the burning, her crowning.

Paradise welcomes her home. The Tree of Life blooms before her. With their swords now sheathed, the cherubim bow to let her pass. Reverently, she extends her hand, partakes of eternal life, and weeps. Abel embraces her. She is whole.

Her head looks toward the blazing throne of God while her arms extend like branches, reaching eternity, and her legs deepen like roots, never fully leaving earth. One by one, the daughters of Eve surround her, a multitude of women, each bearing the crown inherited from their Mother. Some received it in the fire of childbirth, others in the crucible of childlessness, but each is a crowned daughter, uniting with her. Together they stand, the Mothers of all Living, waiting, watching, nurturing, till all their children come home.

Charolette Winder has a degree in English Teaching from BYU and is working on a master’s in creative writing from Harvard Extension School. She has taught seminary and institute and enjoys spending time with her family, reading, and gardening.

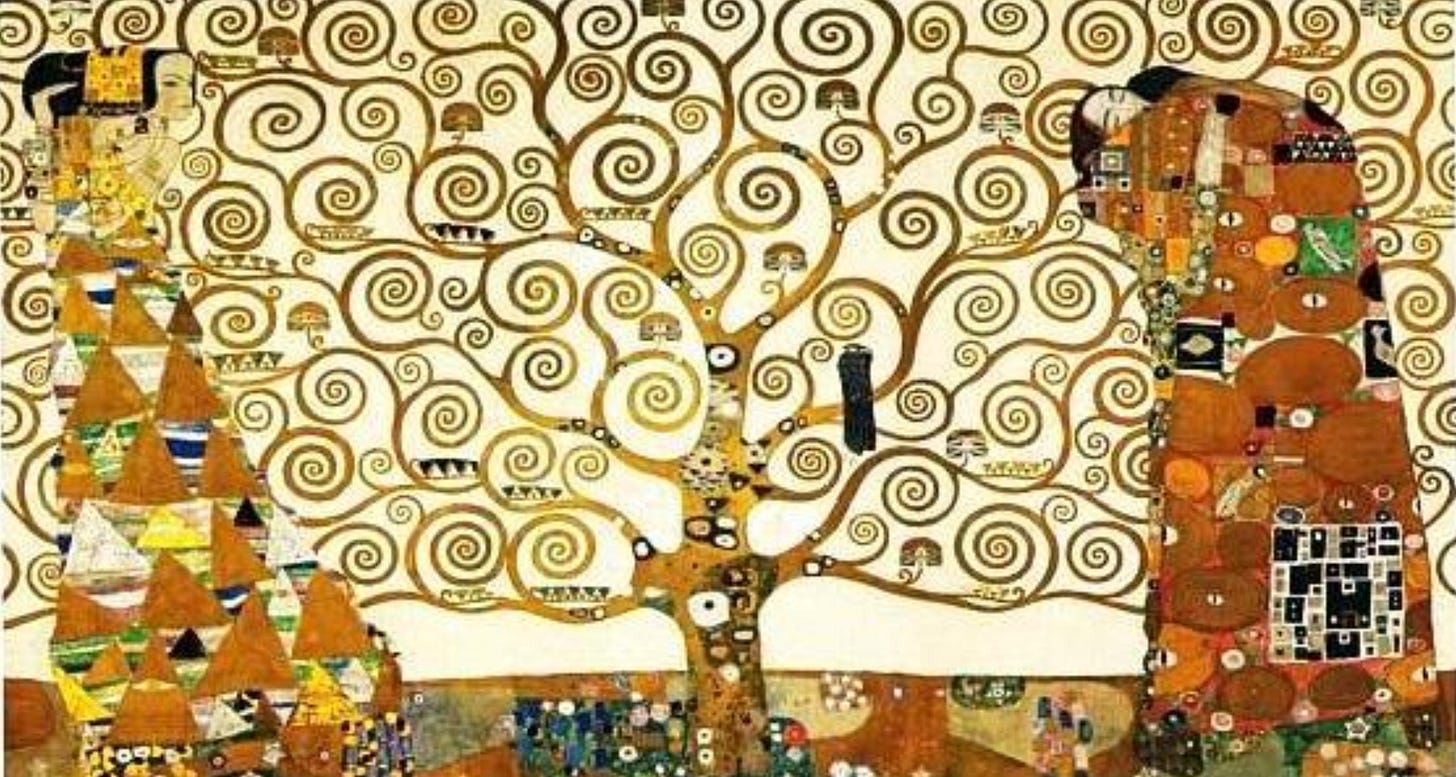

Art by Gustav Klimt.

Brilliant essay, Charlotte!