Arriving at medical school in 2005, I was convinced that I did not belong. I had graduated from a less prestigious school than my peers and was admitted off the waitlist. I figured, for years, that it was only a matter of time until I was found out and, as likely as not, kicked out of medical school entirely.

It’s hardly surprising that I became so eager to learn to fit in. It seemed to me that people who had graduated from the Ivy League were the possessors of a secret code. I wasn’t sure what the code looked like, or even exactly which kind of behaviors it dictated, but I knew that discovering the code and mastering its secrets were fundamentally important if I wanted to fit in.

And, oh, how I wanted to fit in.

Over my first few months at school, it became clear that the code included some important, if subtle, elements. For example, certain words were to be used frequently and others were to be avoided. There was a particular rhetorical and intellectual stance that mattered if you wanted to be respected by your classmates. And, most importantly, it was vital to like certain things and to dislike others—and this crucially included respecting certain groups of people while disrespecting others.

For example, I learned it was important not to voice respect, admiration, or even understanding for anyone or of anything that was “conservative.” Likewise, I soon learned that one class of people who deserved less respect was the religious. True, there was a certain way of holding religion—at arm’s length and with a studied intellectual detachment—that could pass all the appropriate litmus tests. But professors would openly make fun of deeply religious people. And it soon became clear that many of my classmates viewed my religious devotion with puzzled bemusement.

All of this proved fairly confusing. I had grown up in a place where most of the people I knew and loved were, after all, conservative. I knew that many “conservative“ friends and elders in my acquaintance were deeply good. But even so, I recognize now, in retrospect and with embarrassment, that there were times when I began to adopt the language and attitudes of the people around me, even when that included dismissing, caricaturing, or overlooking people I knew to be good.

To be clear, there were luminous exceptions to the above cultural norms. I became dear friends with a woman who had lived for years on the Mexico/US border delivering health care to those without documentation. She then considered becoming a nun but, in the end, came to medical school so she could become a primary care doctor to those in need. Likewise, I developed a friendship with an atheist Jewish woman who showed deep interest in my religion and with a Quaker friend who wanted to better understand my beliefs and what made me tick. In the years since, even though I have trained, learned, and worked almost entirely in secular university environments, I have found many nonreligious people who are curious, selfless, kind, and respectful, including of the things I believe. But none of this changes what seemed the dominant paradigm when I arrived at school.

These memories have weighed heavily on my mind as I have considered the results of the most recent US presidential election. To be clear, Wayfare is not a space for partisan political arguments. We do not support or oppose individual political candidates. That said, Wayfare must certainly be a place for considering the moral health of our politics, writ large. And if the related discussions at times require referencing parties, candidates, and political platforms, then that is a price we pay to have important discussions and ask vital questions.

Without passing judgment on anyone, especially any Church member, it nonetheless seems important to recognize some materially true aspects about our current political moment. One is that the once-and-future president speaks openly in terms that are racist, xenophobic, and misogynistic. This concerns me as a Christian. At the same time, however, there is also a contingent of the Democratic Party, and much of the country’s intellectual “elite,” that seems to want to look at and speak about a huge proportion of the country’s citizens derisively and condescendingly (in private), while also speaking eloquently in public about equality and raising the minimum wage. When people hear Barack Obama talk about rural voters “clinging to guns and religion,” or when they see that Hillary Clinton labels so many citizens as “deplorables,” or when they hear politicians dismissing “traditional Christianity” as antiquated or quaint, they suspect that these are the rare instances of politicians saying the quiet part out loud. What strikes me about all of this is that these examples reflect the same underlying emotional, psychological, rhetorical, and relational impulse, though they come from opposite ends of the US political spectrum: in their different ways, both parties too often speak about and even to others with contempt.

In this light, I have become impressed with this fact: what we urgently need in civil society is the cultivation and promulgation of a deep, abiding, and genuine Christ-like political ethos. We need a Jesusly renewal of our politics. And as we look toward this, the restored gospel has distinctive and beautiful teachings to offer.

I am definitely not talking about Christian nationalism—an idea whose resulting politics can often be deeply unchristian. Furthermore, I am not suggesting that either or any political party has a monopoly on Christian values. Indeed, I have meant to demonstrate here that both sides of the political equation need this Christ-based political ethos.

Instead, I am inviting members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—wherever they live and however they engage in politics—to become active agents in building a politics that reflects restored Christian values. To me, the covenants we make as members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints suggest a specific mode for engaging in the political process. I am suggesting that to live a covenant, restored, Christian life is to do the hard work of making peace and pursuing humility while we approach whatever other political objectives may be important. That is: regardless of particular political agendas, policies, projects, and platforms, how we show up in the political world matters. A commitment to live and engage in a Jesus-following way can be part of the antidote to the poison that is infecting our body politic.

In 1989, President Gordon B. Hinckley (then counselor to President Ezra Taft Benson) delivered the ailing prophet’s address on his behalf. In that talk, President Benson discussed how pride is inherently competitive. Quoting C.S. Lewis, he observed that pride gets no satisfaction in having or achieving a thing, but only in having or accomplishing more of it than someone else—that the animating force of pride is not even acquisitiveness or ambition, but rather enmity. Pride thrives when we make ourselves feel like more because we make others feel like less.

This is a theme that asserts itself relentlessly—uncomfortably—in the Book of Mormon. Indeed, save the 180-year interregnum after Jesus’s visit to the Americas, the book is one long chronicle of the ebbs and flows of division, enmity, abuse, contempt, frustration, and violence, from the initial Lehite band—which fractures into competing clans before Lehi has even died—to the closing apocalyptic cataclysm that sees society disintegrate into an orgy of cannibalism and war.

It is a bleak and haunting vista.

But what speaks so deeply to the political scene in 2024 is that the root cause of the evil and division in the Book of Mormon is both endlessly varied and monotonously the same. The guises never stop changing: the people divide themselves by wealth, by skin color, by education, by ancestry, by land of origin, by clothing, by church, by beliefs, by politics, and on and on and on. And yet the impulse is always the same: they just cannot stop longing for “-ites.” It’s hard to say why this need is so persistent and seemingly universal. It is the defining tragic flaw of every iteration of society in the Book of Mormon and likewise continues to corrode and corrupt society in 2024. Something deeply human tempts us to seize on anything—anything—that can serve as an excuse for seeing ourselves as better than others.

But even as the restored gospel of Jesus Christ outlines for us the depth, breadth, and devastating consequences of this problem, it also suggests a better way. First it reminds us that we descend from the same lineage as God—we are woven from the same fibers and fashioned from the same cloth. In some deeply metaphysical way, we are literal spiritual siblings. The anachronistic nomenclature of “brother” and “sister” serves as a beautiful reminder of how we are meant to see each other.

Charged with this knowledge, it is our mandate to challenge the rhetoric of political pundits or leaders who speak of others derisively or dismissively. We cannot ignore the rhetorical strategy of making those who are somehow unlike us seem less than us because to do so is to baldly deny the most foundational doctrine of restored Christianity, the one many of us learned as little people singing in Primary, “I am a child of God.”

In light of this, I am deeply struck that those who receive their temple endowment are called to leave behind the moral logic of acquisitiveness, enmity, and materialism that defines so much of modern life. A few months ago a good friend recommended to me the book Winners Take All by Anand Giridharadas. This volume outlines how a certain segment of wealthy philanthropists has set up the world such that those who belong to their class are often not required to sacrifice anything but are able to move about in a way that suggests they are virtuously helping the less fortunate. This paradigm comes across as both endlessly slippery and deeply attractive, offering the veneer of virtue while never requiring the pain of giving up what you love.

How telling, in a world too often defined by similar ideas, that the temple first invites us to covenant to sacrifice. That is, the temple’s first covenant lesson is that sometimes, to help a greater cause, we must give up what we actually value. As Jesus taught, we can only find our lives by losing them. Or, as Melissa Inouye observed about Jesus’s commandment to the rich young man: the one thing that seeker seems to have lacked was lack itself.

Other temple covenants sound a similar call. For example, the Church has recently clarified that the covenant to “obey the law of the gospel of Jesus Christ” means to live the higher law Jesus taught while here on Earth—a law that reflects the higher political way we are discussing here. Similarly, except for the sealing ordinance, the crowning covenant in the temple is to consecrate all we have and are to, in effect, the cause of making the world a better place.

The extent of our covenant to consecrate is brought into sharp relief when we read King Benjamin’s words reminding us that the object of our consecration, all the things the Lord has blessed us with, includes absolutely everything we have: the very air we breathe, the trees that grant us shade, the sunlight that powers photosynthesis, the people we love and who teach us, the building blocks that make up the places where we are educated and where we work, and every other entity we will ever encounter—all of these are gifts. Grace abounds around us. And no matter how hard we try, we will forever remain hopelessly indebted—unprofitable servants, indeed.

All of the foregoing is meant to define a particular way of being in the world and, therefore, is meant to determine how we engage in life and, certainly, in politics. We are meant to be points of light, among so many other exquisite points of light, in a world that often seems to be dimming toward darkness.

We are meant to be leaven in the loaf.

We are meant to lift and build.

And so, as we move forward into the political arena, regardless of the vote we cast, we cannot ignore rhetoric that harms. We cannot excuse name-calling, denigration, hypocrisy, vindictiveness, misogyny, racism, or verbal cruelty. We cannot ignore the erosion of the rule of law. We must wake up to the injustice around us and arouse our faculties to learn how we can make the world a better place. We must “do justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with God.”

Sometimes, this may mean an impassioned social media post explaining why a politician’s words are unacceptable. Just as often, and with much more difficulty, however, it will mean being in a space where everyone around us wants to regard those who are not like us with derision or dismissal and being willing to quietly stand up to say, “Maybe it would be better if we didn’t talk about those people in that way. How would ‘they’ feel if ‘they’ could hear us?” That kind of sentiment—that sort of humility—is needed in equal measure in a room full of blatant racism and a room full of intellectual hubris. It is needed by progressives and conservatives. It is needed when a politician calls certain kinds of people vermin, and it is needed when a politician calls other people deplorables. It is needed in every political climate and at every point along any political spectrum. The commitment to that sort of humility and bravery beats at the very heart of a restored Christian life.

And then, perhaps we can consider doing an even more countercultural thing. What if we stepped into public and political spaces and suggested ways that we and those who look, vote, worship, and behave like us can sacrifice on behalf of the greater good? What if we found ways to make public policy and taxation and admissions policies and all the rest benefit those who are not like us? What if we battled tribalism by refusing to be defined by belonging to any tribe? What if we wove together the fraying social fabric one stitch at a time?

In all of this, we can learn from the stunning moral example of those who led the US movement for civil rights. The deep Christianity of that movement—led by flawed but dedicated people—lay precisely in the fact that it was equally committed to candidly calling out injustice and to peacefully protesting against it, while still striving to love those who embodied the very injustice they were fighting. With the authority granted him by virtue of the cause he led and the justice he championed in the face of injustice and hatred, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. could fully command the pulpit when he preached, “A second thing that an individual must do in seeking to love his enemy is to discover the element of good in his enemy, and every time you begin to hate that person and think of hating that person, realize that there is some good there and look at those good points which will over-balance the bad points.” That is precisely the pinpoint of moral reckoning in most political dilemmas—to paraphrase Jesus, it is easy enough to love those who band together with us in a common political cause, but it is much harder to make the brave choice to love those who oppose us.

But that is precisely the trade Jesus asks us to make: we must leave behind contempt, and pick up and carry forever the banner of love.

Most often, the battle to reclaim civility, kindness, selflessness, and virtue will not be fought on TikTok, Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, nor even in the halls of Congress or the pages of newspapers but rather in the “lonely foxholes of the heart,” and then in the small groups—most often of like-minded individuals—where persuasion and epiphanies remain possible. It can happen as we mutually pledge ourselves to the work of recognizing and fighting against injustice while also equally working against the tendency to believe ourselves better than those we oppose. It can be in the choosing of our words and the fashioning of our arguments. It can be in our day-to-day interactions with those around us. It can come in the way we show up in the world: in the arch of an eyebrow, the softening of a word, the firming of a spine, and the refusal to abandon the better angels of our nature to that damning human tendency that is always pulling us toward a world of “-ites.”

I believe in the necessity of this change precisely because I see a need for it in myself. I have often grown frustrated because I have found within myself the seeds of enmity and contempt, even though I am, by nature, a person who avoids conflict and instinctively wants to see the best in others. But that’s just the thing: it’s not that I hate anyone or even think about or treat them unkindly. Rather, it’s that always and everywhere I find myself wanting to belong to some elite group. What I have realized in the many years since I entered medical school is that I must keep relearning the same lesson over and over. First, I needed to fight against the temptation to believe that the “conservative” friends and elders I’d known growing up were somehow less than the people I was meeting in school. But then, just as soon as I came back to learning that truth, I also had to relearn—and many years have taught me that this is true—that my colleagues in universities and medical school are, largely, noble and beautiful human beings who are, to a person, doing their best to make the world a better place.

And that is a great truth that life has taught me. Poisonous political rhetoric, no matter whence it comes or where it is directed, deserves such strenuous resistance because it suggests an idea that is not true. We cannot be divided into good people and bad. We are, all of us, deeply flawed, complex and contradictory. Most of us try most of the time to get things right, and most often fail to get things right, at least completely, because that is the nature of living in a complex, flawed, and fallen world. But if our membership in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints can help to remind us that everyone we encounter in every circumstance—as well as each of the nameless and faceless people who make up the statistics with which politics so often deals—are literal children of celestial parents, then our beliefs can transform our political behavior. They can help us in this arena, too, to try to be more like Jesus. And that, at the end of the day, is what we are always called—and have covenanted—to do.

To receive each new Tyler Johnson column by email, first subscribe to Wayfare and then click here to manage your subscription and select "On the Road to Jericho."

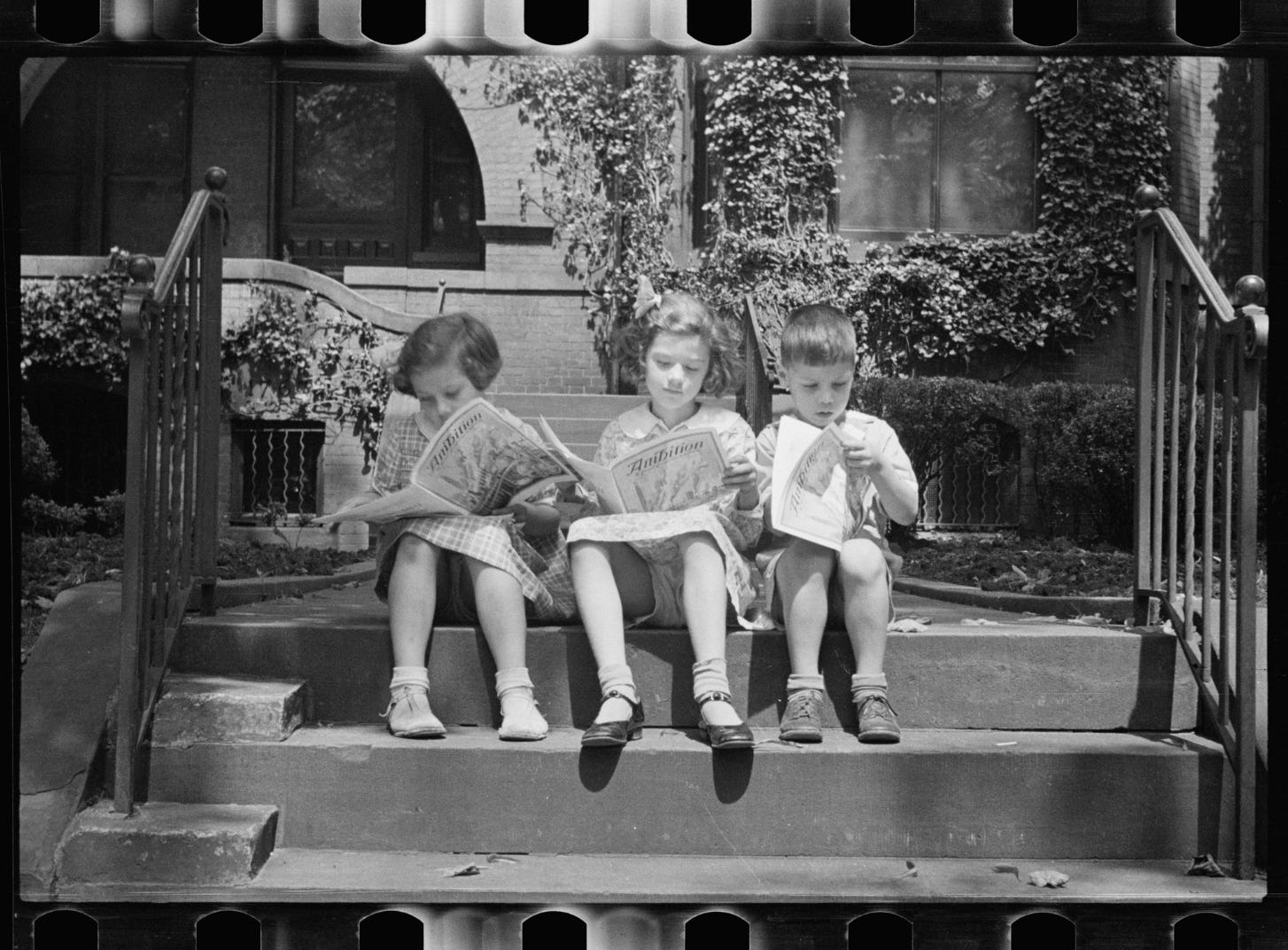

Art from government collections.