Fire and Water

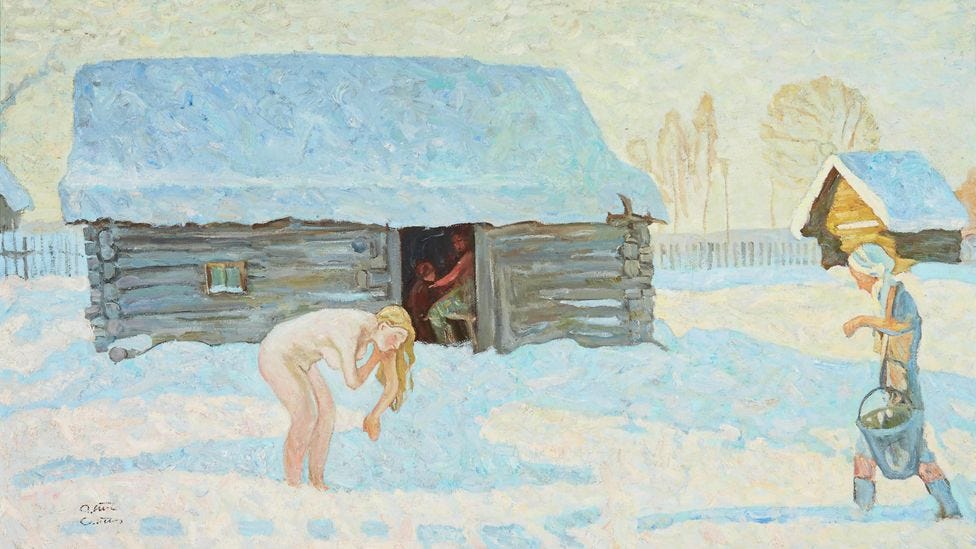

Holding the Tension of Opposites in the Russian Banya

In the Judeo-Christian garden story, partaking of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil precipitates the fall and opens Adam and Eve’s eyes to their nakedness, which is to say, to their brokenness or vulnerability on the one hand and to their physical attractiveness on the other. Nakedness thus serves as an important metaphor in the biblical account for the birth of opposites, namely fear and desire. So, if opposites coming into Adam and Eve’s purview coincides with covering themselves and entering a fallen state, then, by analogy, reclaiming that former state of wholeness would suggest unlearning opposites and uncovering oneself, which is to say, experiencing a second or spiritual birth—naked as it were—and an awakening to the underlying oneness of all things.

In a similar manner, the ritual sauna or banya, as it is called in Russian, recreates primordial space wherein one can transcend opposites and rediscover “the primal source of Life as it was when Life, like the whole of Creation, was still sacred because it was still new from the hands of the Creator.” Accordingly, banya rituals mediate transitions, e.g., women gave birth in the banya to ensure safe passage for the child from the “other” world into “this” world. In the unfortunate event of a stillbirth or fatal complication, a banya ritual helped those grieving move beyond their loss. Experienced mothers performed a ritual banya for young women preparing to become mothers to assist their bodies for the inevitable transformation to come. Banya ritual assisted married couples experiencing a blockage in their physical and/or emotional relationship. Family members brought their ill to the banya, and when healing rituals performed therein failed to produce the intended effect, family members anointed the bodies of their dead in the banya to assist with passage out of “this” world into the “other,” and mourners of the deceased visited the banya to “wash their grief away.” In this manner, banya ritual encompassed the entire spectrum of the human experience from cradle to grave and provided a constant point of reference by which to establish one’s bearings in life’s journey.

Spaces wherein opposites dissolve and give way to a primordial oneness we call liminal. Such spaces reflect in-between places, neither here nor there, between heaven and earth. Some are more concrete than others (e.g., crossroads or door thresholds) whereas others emphasize process (e.g., entering adolescence, going away to college, or getting married). Many such spaces we create without any conscious liminal intent, while others we create with the express intent of fostering transitions and effecting change. The banya creates both physical space, with which one can identify concretely, and a metaphysical gateway through which one can pass when transitioning from one phase of life to another.

It is important to recognize that one and the same space can represent a different experience depending on the level of magnification. For example, on one level this entire earthly experience can be seen as an intermediary or liminal space between worlds during which one undergoes tests and trials that determine one’s inheritance in the next world. We find such a view play out in the Christian mythos in the form of each of us wandering on earth as strangers “from a more exalted sphere;” however, if one examines this earthly experience through a higher level of magnification, one sees that “all life is transition, with rhythmic periods of quiescence and heightened activity.”

The Russian tradition typically has the banya located seven versts from the village, which translates into just over four-and-a-half miles, but we can be sure that such a figure speaks metaphorically to the distance one must travel to come to the edge of the village. As such, the banya metaphorically straddles the familiar world of the village and the unknown and, thus, acts as a gateway from one world to another. Moreover, in the Russian tradition, the number seven holds strong magical power and often is used in spells and legends, so placing a banya seven versts from the village imbues it with metaphysical powers capable of producing the requisite insight and strength to assume new and unfamiliar challenges.

Liminal spaces, such as the banya, on the one hand pose a danger owing to their indeterminacy (hence, in the Russian tradition, crossroads served as the place of burial for those who died an unnatural death) and on the other, hold the potential for effecting change. In other words, the very indeterminacy that can elicit fear likewise can deconstruct otherwise fixed patterns and give rise to entirely new life-giving combinations. Accordingly, transformations presuppose dying to one’s old self in order that one may experience rebirth to a new self, characterized by expanded consciousness. The banya provides a space for such transformations, and ritual—a vehicle.

A man and woman clasping hands over a marriage alter (symbol of a tomb and womb) accomplishes nothing from a purely physical standpoint; however, marriage speaks to more than a mere physical union. Ultimately, it speaks to a metaphysical union—dying to the life of the dyad and experiencing birth to the life of the monad—and since such a transformation eludes impartial measures, one looks to spiritual means, or ritual, to accomplish the intended effect. It cannot be overstated that the power of any ritual resides not in the prescribed words or motions themselves but in the spiritual capacity of the initiate to suspend ego control and willingly brave a new and altered state of consciousness—a subjective state to be sure, but such is any altered or expanded state of consciousness.

Naturally, venturing into the unknown involves risk. For millennia humans have cultivated ways to bridge the worlds of the known and the unknown in the form of ritual that simultaneously creates discomfort for the initiate, who symbolically dies to his old self, and comforts him as he navigates the dark labyrinth of inner space in search of the pearl. The very proposition that one thing can transform into another presupposes a unitary worldview, according to which duality is but an illusion, or oneness in disguise. Ritual thus unlocks the doors shielding our eyes from such a worldview and aids in the miracle of metamorphosis—whether that bе in the shamanic tradition of a man turning into an animal or in the Christian tradition of God assuming human form, turning water into wine, the dead rising from the tomb, or water gushing forth from a rock—the principle is the same: the potential for transformation exists because everything is everything to begin with.

Like temples that unite opposites through ritual (physical bodies acting for spirit beings and temporality merging with atemporality), the banya unites opposites in the form of fire and water, hot and cold, birth and death, cleanliness and filthiness, light and dark, and creates liminal space wherein opposites cease to exist independently of one other and instead return to their original interdependence, which is to say, to their primordial oneness. Writing about Joseph Smith and the underlying liminality of the temple liturgy, Samuel Brown observes: “For participants, the temple had a great deal to say about the structure of the world and their prospects for power both in this world and afterward. There was in that a sense of movement between spheres. God too would straddle the spheres.”

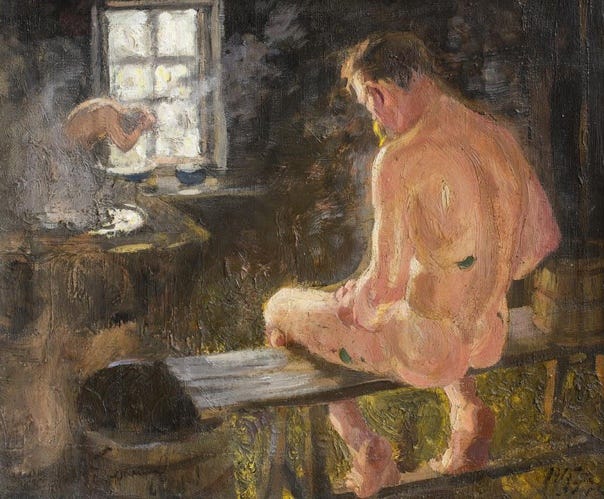

Inside the traditional banya sits a large, wood-fired, open-hearth oven typically in the shape of a barrel vault and made of large stones topped by smaller rocks. Heating rocks or matter (etymologically related to the word mother, e.g., German mater and Russian mat’) and then ladling onto the red-hot rocks water, or the amniotic fluid of the womb, produces a new, purified, and transformative whole third in the form of steam. So, when Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s beloved national poet, dubbed the banya the “second mother,” in part he was alluding to its role as a second or spiritual womb, in much the same way that Jesus, when speaking to Nicodemus, alluded to a second womb. The Russian novelist, Fyodor Dostoevsky, viewed the banya as both “clean and dirty, as pure and corrupt, and as a potential gateway to both hell and salvation. The Russian predicament [is] the human predicament; the human predicament could be summed up by the banya.” Thus, filthy individuals who steam leave feeling physically cleansed, but more importantly spiritually cleansed for they have endured the tension of opposites and reclaimed a primordial unity characterized by a polarity that recognizes opposites as different aspects of one and the same whole.

The wisdom of the banya tradition eludes those who insist on a unipolar vision of the world, for the banya reminds us that cleanliness, both physical and spiritual, has less to do with one-sided purity and more to do with wholeness. Just as wisdom texts convey truths to individuals that coincide with their respective level of consciousness and overall preparation, the banya benefits individuals according to their intent and readiness. Indeed, for some the banya primarily serves as a place of physical cleansing and relaxation, whereas for others it provides a sacred space wherein healing and connection with self, ancestors, and posterity can occur, and to insist on one or the other as constituting the function of the banya is to oversimplify and even denigrate its capacity to embrace and succor the full spectrum of humanity.

Therefore, an experienced banya master will prescribe a procedure that accounts for the individual’s express intent, energy, preparation, and risk tolerance. In like manner, the Indian saint Ramakrishna used to ask those coming to talk with him: “How do you like to talk about God, with form or without?” Like the archetypal wise elder who assists the hero on his journey, the banya master leads those who will into otherwise forgotten or repressed aspects of their psyche and facilitates connection, cleansing, and catharsis. The risk for the initiate, of course, comes in the form of exposure—secondarily in terms of physical nakedness and primarily in terms of emotional vulnerability. After all, as Carl Jung observed, who wants to run the risk of being ridiculed or, worse yet, “offending our real god: respectability.” As such, failure to respect individual intent and boundaries can potentially subject one to experiences that harm rather than benefit and, thus, do a disservice.

For the initiate seeking to move beyond the physical threshold and probe the spiritual realm, the banya, like the temple altar, represents both a tomb and a womb, i.e., a place of endings and beginnings; however, all symbolic deaths and rebirths require an initiate who voluntarily places her ego on the altar. Accordingly, in Russian fairy tales, threshold guardians, ask the hero the same question: “Did you come here of your own free will and choice?” In other words, unless someone desires to embark on a journey into oft neglected aspects of the soul, then no amount of ritual and steam can produce the intended effect.

And so, the person who disregards such a universal axiom and attempts to impose Aristotelian logic where it is forbidden will ultimately experience a self-fulfilling prophecy in the form of confirmed skepticism and disbelief, and precisely in this manner, sacred spaces such as the banya shroud wisdom and truth from those unprepared to receive it.

Tony Brown is a German and Russian language professor at BYU.