Bitter Water Opera, a 2024 magical realism novel by Nicolette Polek, is a pilgrimage and a heroine’s journey and a puzzle box and many other things. But mostly, it is a ghost story, one where the heroine chases the lives of ghosts instead of living her own.

On occasion I find myself hiding. Usually, I hide from my children, but I also hide from writing and cleaning and going outside and touching grass. And when I hide, I distract myself with video game streamers or sporting events or whatever content the algorithmic gods bestow upon me. I search for contentment in distant events I cannot control; I avoid the vulnerability and work of everyday life. During these acts of self-concealment, I sometimes ask myself, “Why am I doing this? What am I doing with my life?” In other words, “Why am I avoiding living my life in favor of whatever this is?”

Limerence is an intense, often involuntary and unreciprocated, longing for another person to the point of persistent fantasizing and obsession. In Bitter Water Opera, the heroine Gia doesn’t experience limerence for another person but for other lives, for “another world that destroyed all joy” (70).

The book unfolds in four parts. In each, Gia pursues one or two different lives. Part one shows Gia’s current life falling to pieces. She’s taken leave from her university position; she sleeps more than half the day; she has destroyed her relationship with her partner. Within the first few pages, she sends a letter to the ghost of Marta, a woman she has admired, hoping that Marta will “in some act of imitation on my part . . . fix my life” (10). Marta arrives, bearing cigarettes and lime-green shoes. Eventually, Gia tries on Marta’s shoes, but she cannot step into Marta’s life, even in her own imagination or imitation.

Having tried unsuccessfully to fit herself into Marta’s life, Gia tries another life, one which “involved starting many projects, planting many seeds, and knocking on many doors, openly accepting invitations and pursuing any and every innovation one desired within reason, with the calm understanding that some efforts wouldn’t fully succeed” (66). She retreats to a colleague’s secluded cabin in the forest. She attempts to tend the overgrown garden as she also attempts to tend her own life, scrubbing and weeding and passing through a dark night of the soul. After that dark night, she attends a church service, planting a single pear tree before planting fruit tree after fruit tree after fruit tree. She prepares a sumptuous meal, which she then consumes down to the last crumb. But she doesn’t seem satisfied.

Is this second life better than the one she had before? To both the reader and to Gia, the answer seems a resounding yes. But there is still work to do because she is still engaged in limerence; she is still seeking for a life other than her own. Indeed, repeatedly throughout the text, she presents false dichotomies of these limerent lives: “There seemed to be two ways of living that I’d encountered up to that point” (66), one of which was her modern academic life slowly leading towards ruin. She says of that life, “[w]e were all being bested by an educational machine that ran on spurious promise, a part of some larger cultural milieu of restlessness and indecision, shame and lack. It was as though everyone was involved in elaborate and too-secret cover-ups of their own selves” (31). As mentioned above, she tries on Marta’s life, but she can’t just change her life as she would her shoes. At another point, Gia “imagine[s] two doors” (35) each leading to lives different than those already described. Again and again she pits these lives against each other, seeking one that will satisfy. As she describes in her letter to Marta: “At night I drive on the highway. I pull towards exits that go somewhere far. I switch lanes, but never end up leaving. I cannot bring myself to leave the things that make me small” (5).

In part three, Gia passes through Death Valley (or the valley of death) and the nearby opera house built by Marta and her partners when still alive. Despite the efforts of three dedicated caretakers, the opera house is crumbling as tamarisk trees (that is, living plants) uproot and destroy the foundation and walls. While there, Gia drives deep into the desert and experiences the sublime as she is “surrounded by emptiness and [doesn’t] wish to fill it” (100). Indeed, in contrast to the smallness she expresses in her original letter to Marta, she becomes “small and unnoticeable, but it [is] a smallness where something wonderful” surges around her. She feels that the smaller she becomes, the more she can see this wonderful thing (100).

Though the foregoing description might seem to reveal too much—especially for a book barely more than 120 pages, many of those pages having only half a page of text—the nutritional density of the book far exceeds its pages and dwarfs the descriptions here. In beautiful, poetic prose, Polek layers color and nature and ontology and theology and scripture and creation. The book demands rereading, annotating, turning back to see the last reference to a heron, to the wind, to candles, curtains, colors. It plumbs the past and future, both of which are illusions, ghosts to be chased. Only in the present can we be present. The juxtapositions continue with the artificial versus the natural. The natural—the non-artificial—is where the sublime, or God or however you want to describe that which is outside the self, resides and works on us.

The sublime is not found in hiding from one’s children, in avoiding vulnerability, in digital content and passive consumption. Those activities are ghosts; they are dead things and ruinous. To close with a quote from the text:

Anything can be haunted if you wish it to be. . . . Ghosts are tumors of the imagination. Instead of renovating old hospitals, abandoned factories, you permit them to decay. You celebrate stagnant, broken forms and shirk the responsibility to bring them back to life. . . .

You spend obscene amounts of money on plasma detectors and high-definition microphones, nonsense equipment, just because you don’t know how to clean debris from a room to imagine new possibilities. Instead you take pictures of lost towns where life has passed through them like a sieve. Instead of innovation you take an opera house like this and turn it into a site for your irreverence. (109-110)

The book invites us to plant gardens instead of preserving ruins; to seek the living rather than the dead.

Ryan Fairchild is a former entertainment and technology lawyer who now stays at home with his three children and is much happier for it.

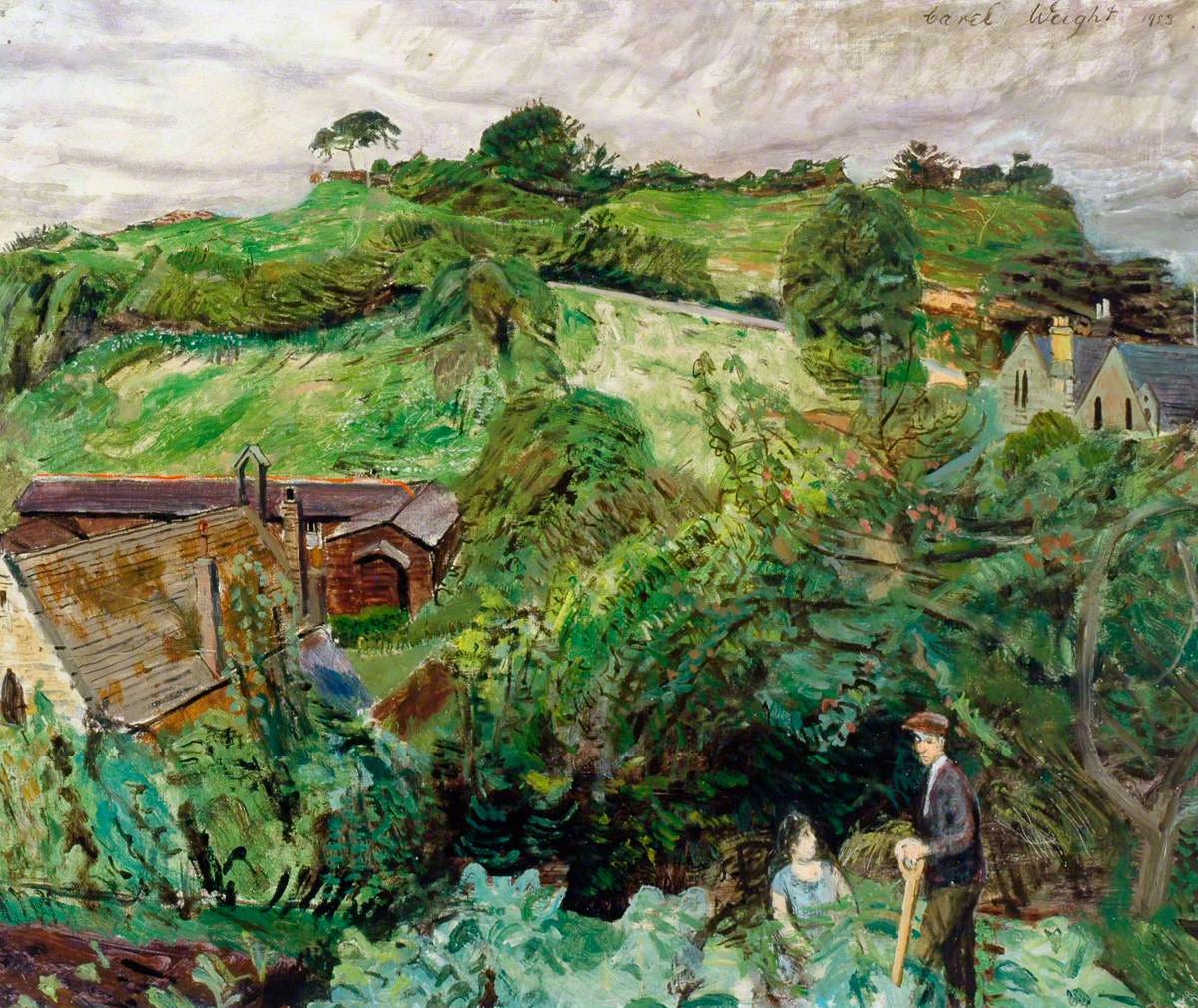

Art by Carel Weight (1908-1997).