Falling Into Paradise

Nobel laureate Derek Walcott begins his epic poem Omeros with a story of a festering wound that won’t heal. The story is rich in symbolism: the wound was inflicted by the anchor of a sunken slave ship, and the plant that ultimately provides salvation grew from a seed that had been transplanted from Africa, borne by a swallow. The wounded fisherman bathes in water suffused with this plant inside of a rusty cauldron that had been a part of a former slave plantation. Walcott describes him emerging as if from a baptism, like a second Adam in a new world. For the characters of the poem, healing does not come from repression or neglect of history’s wounds or from perpetual cries for revenge, but from accepting and transforming the meaning of the conditions that those wounds left behind. Walcott’s native island of St. Lucia becomes, then, not a cursed vestige of a violent colonial history but instead what he calls a “self-healing island.”

Many years ago now, following a surprise opportunity to interview Walcott in a public forum, chance events had led to him becoming something of a literary mentor for me. His bald assessment of some of my poetry was that I was trying too hard to “sound like a poet,” and he urged me to write prose for a while, to try to quiet my voice down, to be anonymous. I dutifully spent the next year drafting prose about my meditations on the Provo River, an experience that became the most deeply satisfying writing I had ever undertaken. However, I was completely unprepared for Walcott’s response. He wanted to know where all the pain in my writing came from. His questions persisted until he learned of my older brother's suicide when I was eighteen.

“Ah, well that explains it,” he responded.

“I really don’t know what you mean.” I was surprised by how annoyed I felt, but I tried to disguise it.

“Pain behind the prose—I can feel it. Have you ever written about his death?”

“No.”

The truth is, not only had I never written about it, but as the years had passed, I found talking about it increasingly difficult and rare.

“Well, then, now you know you have to write about it. It will be the hardest but most important writing that you will ever do.”

“That is not going to happen,” I said.

“You will thank me later, but you must do it,” he said calmly. I was angry at his intrusiveness and his insistence. But after our conversation that night I had a dream that brought me strange peace, and I awoke knowing I would have to write about my brother. As I began in earnest, repressed details came back of that terrible December day, which sent me to my parents and my surviving brother to fill in the blanks. Though difficult and tearful, those conversations were some of the most important our family had ever had. They resulted in an essay about my brother’s death that later became a chapter in my book, Home Waters.

As I was preparing for the final publication of the book, a trusted friend read it and told me that I was waiting too long in the book to tell the story of my brother and saying too little about my family in general. The poignancy of that event, he felt, almost felt dishonest to delay for so long. Putting it earlier in the narrative, however, was going to be logistically very difficult, and it also raised more existential questions for me. Was I writing a memoir or a book about a river? What, finally, was my story in the expansive context of where I lived?

As I tried to answer these riddles, one fishing memory emerged and found its way into the first chapter. I was sitting in my car with a friend just after moving to Utah. Heavy rain had chased us off the river, and we were waiting to see if it would clear. I found myself telling him the story of my brother’s suicide, something that was at that time still hard for me to talk about. He then startled me with the story of his own mother’s suicide. As I wrote this scene for the book, I described myself looking out the window at the rain on the river and hearing my friend say, “This bullet that ripped a hole through his head and through your life is the reason why you crave friendship and why you love this river.” No sentence I had ever written up to that point was more painful to write or more truthful, and it was the last sentence I added to the book.

Walcott had been right. There was a reason, a deeper personal reason, I was drawn to the river and loved to write about it. I was wounded and needed healing. It didn’t convey the whole story to say my brother “killed himself.” He died of an illness. His body betrayed him. His chemistry failed. Something took from him his ability to enjoy the pleasures of an embodied life, and as best as I could figure, it was nature itself that had taken it. This left his suffering without an answer. The question was: why, if nature was the very reason for my suffering, did I think it could heal me?

Nature already knows how to heal itself. It persists in the face of the insults and injuries we inflict upon it, something not unlike Christ’s command to turn the other cheek. This shouldn’t ever be interpreted to mean, of course, that we should injure nature or that we can’t do irrevocable damage to it; in fact, its meekness, like that of children, only highlights the injustice of our abuse. Many believers and critics alike have misunderstood Christ’s call to meekness as a call to weakness, to indifference or acquiescence to injustice or to pain. This is a profound distortion of the truth. Christ does not right wrongs like a mighty knight errant, but when we turn to Him in our brokenness, He rewrites the meaning of our story. The facts of our lives do not change, but His power seems to rearrange the furniture of our minds where facts have settled, freeing them from the appearance of inevitability and of fixed meaning.

Section 88 of the Doctrine and Covenants offers a clue as to how intertwined Christ’s healing power is with the natural world. The revelation tells us that Christ is in the light of the sun and of the moon. He is the light that gives shape and color and form to all things. He is the present force, the loving guarantor of a continuous creation. And while this miracle takes place around us daily, we scarcely notice, ironically, because we are too busy nursing the very wounds Christ’s creations can heal. Or too busy repressing them, running away from them. I sometimes wonder if our greed and materialism are just symptoms of our unhealed wounds. Instead of turning to Christ, we use and abuse nature as a material resource to numb the pains of life even while we praise its exotic beauty.

Some drugs heal, but some, of course, only shield us from pain without getting at the root cause. Our faith in Christ can bring healing, but we can also use it as a palliative no different than any other painkiller or material luxury. I have often worshiped a false god who I hoped would simply erase my past and my pain, erase my mistakes, and place me back in that mythical Eden that we imagine lies outside of time and beyond this earth. But instead, the living God provides many small edens on this earth, moments of real and raw and imperfect beauty (is there really any other kind of beauty?) that penetrate me and raise me to new levels of consciousness.

I don’t know how to distinguish such moments from the many experiences of forgiveness that my faith in Christ has brought me. In nature and in repentance both, it seems that my sorrows and my sins are not so much taken from me, as if they never happened, but transformed, as if I just mistook their meaning. In my moments of highest exultations on a river, on a mountain, in the deep forest, watching the sun rise or set, like Walt Whitman I let loose my own barbaric (and holy!) yawps in celebration. I am convinced we humans haven’t fallen out of paradise. We have fallen into it. The so-called cursed conditions of this life are the very conditions of our healing and redemption. This planet is our self-healing island.

Maybe we have misunderstood what it was Jesus was offering. He spoke of a kingdom but insisted it started within us. If I knew I would die tomorrow, I would spend my last day praising God for the paradise he gave me here with my loved ones in the loved places we lived. I see no reason to believe that paradise in heaven will be any different than it has been here. Here it has always been mixed up in my own imperfect and particular life, the bruises and tragedies and heartbreaks that have broken me open to God’s glory. Elation is proportionate to sorrow but then surpasses it, just enough to know that it is not an illusion. To paraphrase William Blake, this earth’s beauty has taught me to weave joy and woe together into the finer garment of my life.

At the end of my journey of composing Home Waters, I began to speak of the “healing power of nature” as a refrain. I now see how much more generously available this healing is, even or especially when it isn’t attached to the name of Christ in any overt way. Millions of God’s children feel healing daily from the beauty of the earth, the perception that life is a miracle, or the heart-swelling that is inspired by a joy that reaches beyond common understanding. And no small measure of our human creativity in poetry, music, or art is a response to such experiences. So generous is the Creator that it hardly seems to matter, at least initially, that people understand the source of such healing. It is as if He gives all without any demand for recognition, without any precondition. He is the ultimate anonymous artist.

But something happens when we finally find the courage to say His name, to recognize His suffering on behalf of all Creation, and to praise Him in His creations. The earth that was our exile becomes our heaven. And what can we do in response other than to recognize, appreciate, share, and steward His generous gifts of the Creation? We find more healing, more joy, and more courage to take up Christ’s cross, to learn His capacity to suffer all things. The Czech philosopher Erazim Kohak expresses this poignantly in his remarkable book The Embers and the Stars: A Philosophical Inquiry into the Moral Sense of Nature:

When man goes into nature, it must be a place of remembering, not of forgetting. Away from palliatives and distractions, the pain does not subside: it stands out in all its purity, purged of all self-justification and self-pity. What remains is pain, pure and clear as a bright crystal. There is no distraction, no escape. And yet something does happen, slowly, silently. The grief does not grow less beneath the vast sky, only it is not reflected back. Artifacts reflect grief. . . . The forest is different. It lives, it absorbs the grief. . . . When humans no longer think themselves alone, masters of all they survey, when they discern the humility of their place in the vastness of God's creation, then that creation and its God can share the pain.

Oh how I treasure these words. What truthfulness they convey to me. The very rocks around me on the trails I hike are not so impervious and solid that they cannot absorb and share my pain. I could build a mansion of beautiful walls and furniture, and every object of my vanity would reflect my pain back at me. The created world, on the other hand, is alive. It forms an embedded network of shared grief that becomes, slowly and silently, a shared joy. Immersive experiences in the vast expanse of a forest, an ocean, a mountain, or standing in the middle of a river lighten our burdens. Who does not know this is true? At first, I didn’t really understand why this was the case. I had only a vague sense that this was just a symptom of better physical and mental health. It was, but that health signified something transformative and healing at work deep inside me. My burdens weren’t lighter because nature helped me to forget. My burdens were lighter because I finally realized that nature was helping me to see, understand, and accept them. Memories came to the surface, like deep slivers that had to find a way back out. As Walcott surely must have intuited when he urged me to to confront my brother’s death, I was coming to nature in the same spirit that I was coming to my Savior, as a broken vessel. And in proportion to my sorrow, my joy deepened. And then surpassed my sorrow.

The strange and wonderful logic of the Atonement is that the cause of our wounds also holds our cure. Nature reduces us, humiliates us, pulverizes our ego and our sense of our own centrality. But, enlivened by God’s breath, this becomes nature’s gift, its recompense. Like Job or Moses, as we witness the creation, we discover our nothingness and our newfound and healing significance in the same moment. This does not leave us callous any longer to the suffering of nature or of our fellow beings. Once we become properly yoked with Jesus, we are expanded and become more than our atomistic selves. We become our brother’s keeper and stewards of all of His creations. The natural world brings gifts without price, recompenses of wonder and elation and solace. I know of no more adequate response to such generosity than devoted, compassionate love for every one of His creatures.

George B. Handley is Professor of Interdisciplinary Humanities and Comparative Literature at Brigham Young University and author most recently of The Hope of Nature, If Truth Were a Child, and the novel American Fork.

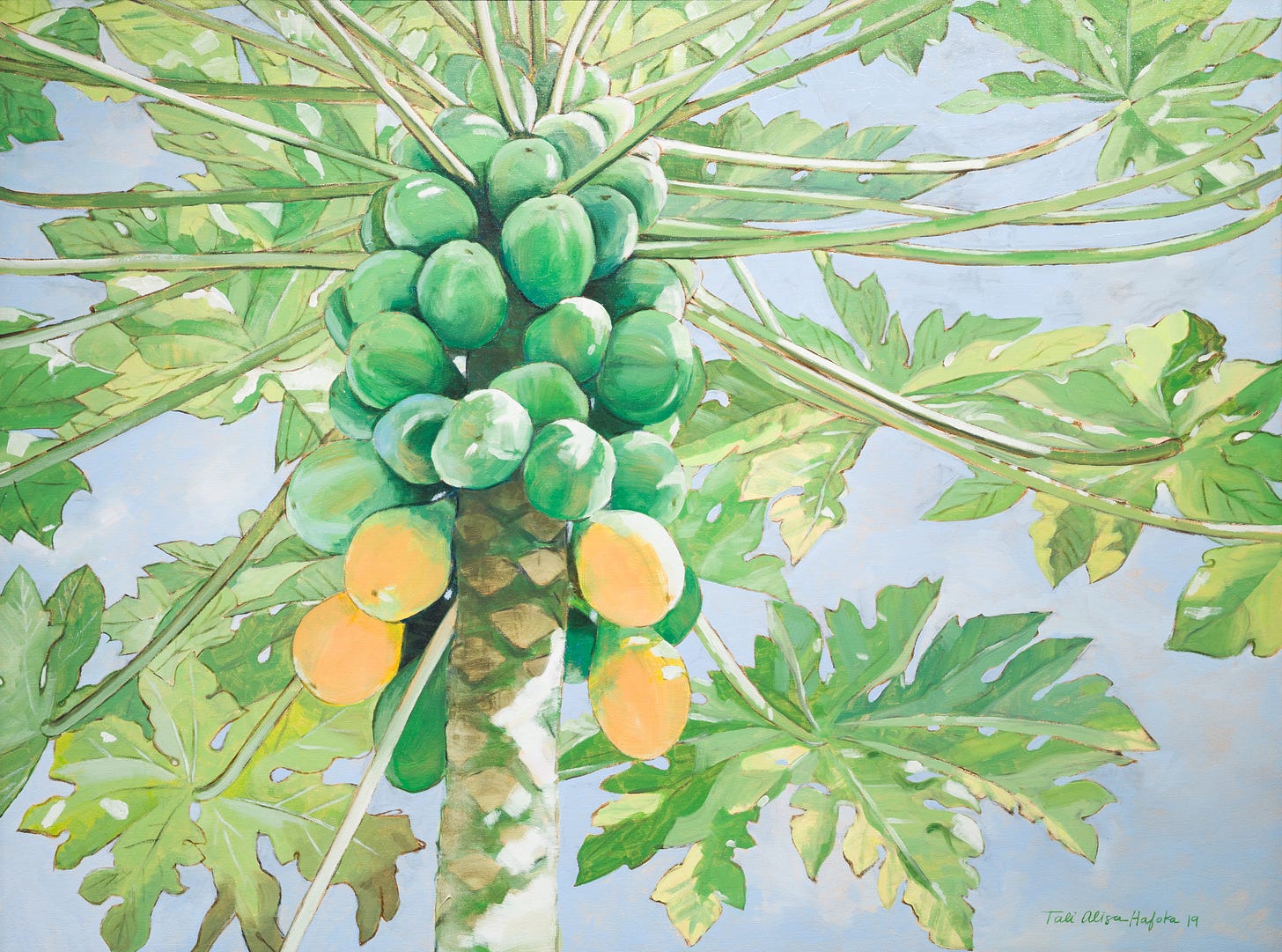

Artwork by Tali Alisa Hafoka.

What a moving essay. This one will stay with me for a long time.

George is a beautiful man who writes beautifully. I am grateful for his honesty and his openness.

As the author of Hebrews wrote, it is a dreadful thing to fall into the hands of the living God. Or, as one midrash puts words into God's mouth: I heal with the weapon with which I wound. The Lord gives and the Lord takes away: blessed be the name of the Lord! May we learn from Him to love our brothers as ourselves and find mercy by being merciful.