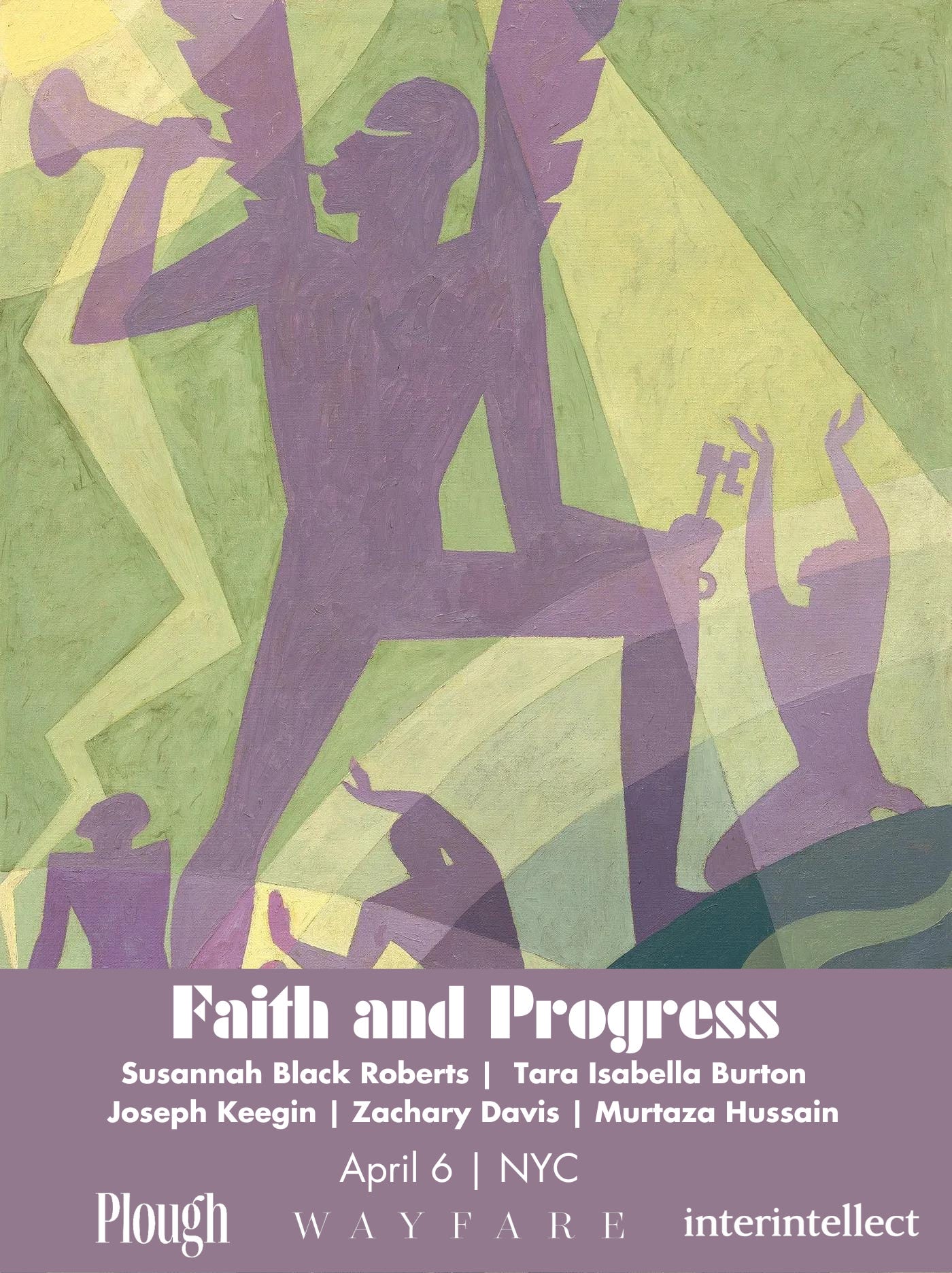

Faith and Progress

An Investigation

On April 6th, 2024 Tara Isabella Burton, Susannah Black Roberts, Murtaza Hussain, Joseph Keegin, and Zachary Davis discussed the relationship of faith and progress.

The follow are the introductory remarks by Zachary Davis.

Nobody seems that happy. Nobody appears to be invigorated with purpose, vision, creativity and abundant life.

Instead of moving forward in confidence, our culture, our civilization seems stagnant, exhausted and full of doubt.

What is wrong?

Many things!

Declining birth-rates, historical guilt, an economy premised on scarcity and precarity, dehumanizing technologies, hyper-individualism, the death of God. And there are many others!

But I want to focus my initial reflections on how the way we think about the shape of history can affect for good or ill our sense of individual and social flourishing in time.

Many early civilizations, like the Egyptians, Babylonians or Greeks believed that history happened in cycles. Like the rising and setting of the sun, or the regular passing of the seasons, nations would naturally undergo periods of birth, flowering, decay, death and then rebirth.

There wasn’t much one could do to alter these cycles, they followed a cosmic order, a natural rhythm. And there wasn’t really a purpose to history. At best it was a playground for capricious gods.

A different view of history began to develop in Jewish and Christian thought. For the writers of the Bible, history was not a series of unconnected events but the vehicle by which a loving God realized his purposes for humanity. The creation, the resurrection of Jesus, and the last judgment gave history not only a beginning and an end but a direction. Time was no longer a meaningless loop; it had become an arrow speeding towards a divine destiny. Deep purpose was found in understanding the arc of that arrow and aligning oneself with its movement.

That began to change during the Enlightenment. Instead of God directing history, thinkers like Voltaire and Kant began giving a starring role to human reason. The purpose of history became less about preparing humanity for a paradise in heaven and more about achieving progress here on earth. Still an arrow moving forward, but flung forward by purely human hands.

Enlightenment visions of progress have focused on values such as freedom, equality, reason and mastery over nature. All wonderful gifts, but as the Romantics recognized, such gifts aren’t enough to fill the human heart. I think the ennui and malaise so many people feel today is because ordering a society around an entirely Enlightenment vision of progress is inadequate for creating conditions of deeper joy and flourishing.

The Enlightenment vision also overly equates progress with newness.

Ross Douthat’s book The Decadent Society is a brilliant synthesis and diagnosis of decadence, convincingly pointing out that our fashion, movies, technologies and political debates really haven’t changed that much since the 1970s. He really, really wants a good, new movie that isn’t a sequel!

But I found myself wondering, why is Ross Douthat, a committed Christian, so hungry for newness? Why is novelty or change itself assumed to be a sign that a given culture is on the right track? Aren’t Christians seeking not newness, but to faithfully live an ancient revelation?

That witness will of course look a little different depending on the time and culture a Christian is living, but expressing newness for its own sake isn’t in my view really the purpose of a Christian life. Rather it is to continually breathe fresh immanent life into eternal transcendent forms. To create a harmony between material, embodied reality and immaterial ideals.

In other words, the best view of history is neither a circle nor an arrow, but a combination of the two. A spiral.

Let me give an example from my own faith tradition of how this might look in practice.

Joseph Smith, the Mormon prophet, was born in 1805 in upstate New York and grew up amid the spiritual ferment of the second great awakening. He prayed to know what was true and visited in a small forest clearing by two beings, God the Father and Jesus Christ, who called him to restore the lost truths of the early church.

Many other Christian movements at the time felt a similar desire to recover or restore so-called primitive Christianity, to remove all the accumulations and get back to the simple purity of New Testament Christianity.

But Joseph Smith’s understanding of Restoration turned out to be quite different and more radical and I think fascinating and instructive even for non LDS people.

Joseph Smith did begin with some restoring work you might expect: he brought back primitive church offices, like that of apostles, teachers, deacons. He sought and manifested gifts of the spirits, like speaking of tongues, angelic ministration, etc.

But then it gets weird!

He restored the idea of God speaking again. Both by bringing forth the Book of Mormon, a set of scriptures, and also by receiving new revelations directly from God. There are hundreds of “thus saith the Lord” proclamations that Joseph received.

But it gets even weirder still!

He brings back temple worship, something that Jews themselves stopped in 70 AD. He creates new priesthood powers, one named after the mysterious biblical figure Melchizedek. And most infamously, Joseph brings back patriarchal polygamy, until the United States military snuffed it out of Utah. Mostly.

All of Joseph’s theological work in my view was spiral-like. It was a creative, dynamic re-cycling of inherited forms to create genuinely new, vital combinations. It linked old and new together in a sacred harmony.

Now, even though Brigham Young’s sexual lifestyle is currently being celebrated in New York Magazine, I’m not suggesting you all become Mormons. But rather, that there is probably a reason why most observers point to Utah as being the least decadent place in the West. It is a spiral culture, a people grounded by the circle and invigorated by the arrow.