When you think of the word mass media, you probably don't think of new media. Usually, mass media means radio, television, film, newspapers, and magazines and new media means smartphones, social and digital media, and the like. But the separation between mass and new media has emerged over time and sometimes to a muddying effect.

Gavin Feller turns back the clock in his brand new book, Eternity in the Ether: A Mormon Media History from the University of Illinois in 2023. He brings us back to the twentieth century when mass media were new media. The book makes sense of how a small but globally mediated religious community emerged uneasily into the twentieth-century era of mass media, which this book makes sexy and weird again, and then goes on into the current internet era. This interview then is not just about globalizing media, it's also a consequence of the same. Namely, our discussion today has Gavin in Brazil and me in Germany giving a podcast interview for a print-digital magazine based out of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Long may US-centric media talk sound appropriately bucolic.

Gavin is both a media producer and company founder as well as an LDS scholar of media and a scholar of Mormon media. We're discussing his new book Eternity in the Ether, which began arriving on scholarly shelves in March 2023. In my view, the book provides remarkable originality, a breadth of approach, graceful prose, and a gripping composition. It marks a signal contribution in a surprising bumper crop of recent Mormon media scholarship: Jon Bialeski's Machine for Making Gods, Mason Kamala Allred’s Seeing Things, and precursor works by the brilliant Rosemary Avance, among others.

Benjamin Peters: Welcome, Gavin, and tell us a little bit about it. How did you come to write a book that Jeremy Stolow calls “essential reading for anyone interested in media and religion.” Where do you come from? Why did you write this book?

Gavin Feller: This is both fun and a bit tricky to talk about. My Mormon faith influences how I think about media and Latter-day Saint history alike. I grew up knowing our tradition’s warmth and folklore as the fifth of eight kids in a family from a conservative Mormon community in northern Utah. I also have a background in media production, and I hope my comfort with the technical and logistical side of media helps more than it hurts the book. I once wanted to be an indie rockstar; that didn't pan out. And so I chose academia as the next best option. I wrote this book as an extension of my PhD dissertation. It is the culmination of years of research I have been doing on Mormon media in academia. One of the first things I wrote was about Mormon religious memes. That early work got me excited about the possibility of doing more Mormon media research. I wrote about Mormon feminist blogs, early radio, and other pieces. I decided to write my dissertation as if it would one day become a book first for media scholars and then for lay Mormon readers, Mormon historians, and others connected to the Latter-day Saint tradition. That became the basis for this book we are discussing today.

Benjamin Peters: Thanks so much, Gavin. Terrific. So, and I’m trying not to miss the buried headline here, if you could have been an indie rock star, what would have been your favorite instrument?

Gavin Feller: I'm better at the guitar but I really enjoy playing the drums. Give me a cool kind of math rock riff and I’ll jam out any day.

Benjamin Peters: That’s fantastic. You write for media scholars first, but you write in a way that makes it enormously accessible to the educated lay reader, opening it to a very broad audience in and beyond the faith tradition. Let’s take a bit closer look at the book itself.

The intro begins by noting that Mormonism, and even all American religions, is best understood through what you call “weird media theory” in which the Mormon media imagination goes between things. It is reliably in the middle, and so your book asks throughout, how has Mormonism managed a middle way through its media negotiating, from early radio to social media?

Chapter one develops how Zion itself, particularly in the restored Gospel, appears as what you call a “media technical project.”

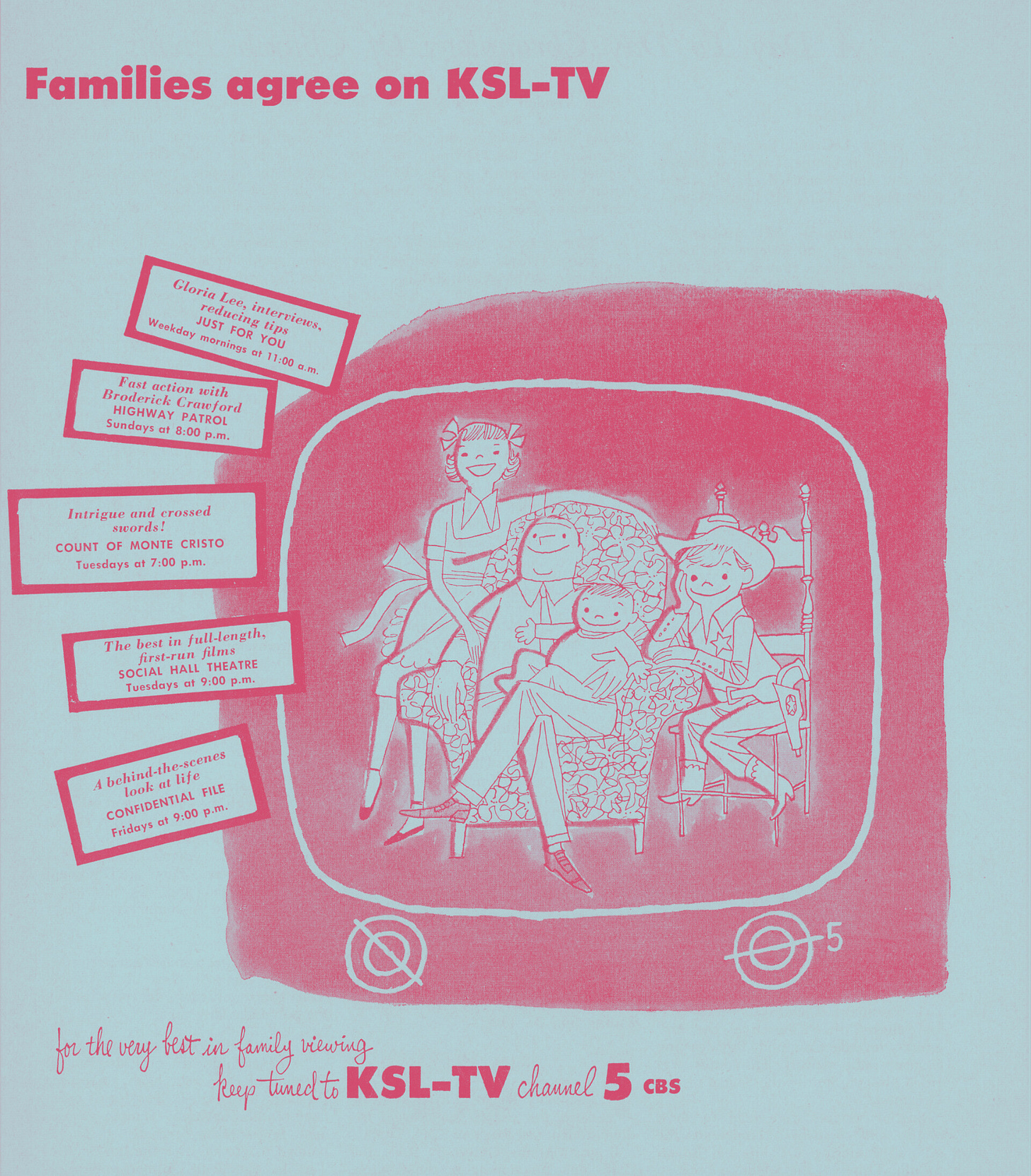

Chapter two remarks on how radio navigates between institutional failures and successes like KZN and KSL. In fact, the charming image on the book cover comes from a KSL advertisement in the Improvement Era magazine from 1956 which surprisingly promotes, in a church magazine, TV as bringing the family together.

Chapter three then mediates the staged institutional cage match between science and religion, and particularly how early radio mediates what you call, in a beautiful phrase for acoustic and religious realities at once, “the reality of the unseen.”

Chapters four and five then offer what television can teach us about mid-century Mormonism. Chapter four treats the institutional compromises that the LDS Church faced in supporting tobacco advertising, another fascinating topic one would not expect in church media. Chapter five treats the threats to (and of) the nuclear family in a nuclear Cold War through the television.

Chapter six and seven then trace the early internet (as generational thinkers, I wonder if we are still today in an era of early internet) across alternative heterodox Mormon discussion boards and the mainstreaming of the internet through mormon.org, lds.org, familysearch.org, ancestry.com, and others.

The final chapter considers social media while the conclusion returns us to Zion as a media technical project that ranges between cosmic ambitions and classic institutional compromises. Every chapter charts the early romance and then disenchantment of our emerging religious community with whatever the new medium of the moment is: radio, television, the internet, or social media. Across all these new media emerge historical cycles of excitement, threat, and compromise. How’s that for starters? Anything you’d like to add?

Gavin Feller: Yeah, I think we can stop the interview right there. I am glad you are able to summarize, make sense, and find the cohesive takeaway across it. Thanks! For those listening who don’t know, Ben here is an established media scholar and media historian. So I’m sure you, Ben, know perfectly well this pattern of excitement, threat, and compromise throughout media history; that argument is not at all new, but what I’m trying to contribute here is an application of that cyclical theory of media historical change (which really fired me up in graduate school as a new way of thinking about technology) to a specific case of one institution across time—the LDS Church. I don’t think that application of this general communication history with more detailed empirical studies has been done for the LDS Church before this book.

Throughout the book, I seek a middle ground for rigorous media historical work, as well as some interviews and textual analysis. In this book, I seek to bring together different methods to see how the larger general claim about media change moving through excitement, threat, and compromise plays out in the details of history.

It is worth stressing that this is not a documentary history of LDS or Mormon media, given that Sherry Baker and Dan Stout, now both retired BYU Professors, had, together with their students, done great work putting together a very helpful detailed timeline of Mormon media and communication history. My book doesn’t try to document or cover every event. Instead, it traces how a continuous single institution tried to negotiate a middle ground between theories of media change and pivotal moments of theology, doctrine, policy, and economic changes. It is not enough to say we have an overarching media history of excitement, threat, and compromise: rather we need to spell out which excitements, which threats, which compromises–how, why, and when. Here--in tracing a single institution across time over its shifting social, theological, and institutional positions: which excitement, which fear, which compromise--Eternity in the Ether adds granular detail. If the book succeeds, it is in bridging high theoretical, historical, even philosophical approaches with concrete, nuanced case studies.

Benjamin Peters: Thank you for such a fantastic description. Just to repeat what I’m hearing, you repeatedly describe media religions as “ways of seeing,” and in this first book-length Mormon media history, you are making a move particular to the genre of media history. Namely, you are synthesizing between larger themes as well as grounded details, without fully devoting your argument to either the abstractions of the theologian and philosopher or to unearthing every footnote of the hard-bitten historian.

Gavin Feller: Yes, I think the danger of trying to do good work, which is necessarily interdisciplinary (a term that should mean a lot less than it does), is that one can step on everybody's toes. At least this book aims to be an equal-opportunity toe-stepper: it will be sure to disappoint historians hungry for the fully documented depth and history the LDS Church media experience deserves. (That is not yet possible given that the Church has limited researchers’ access to some of its proprietary records.) On the other side, the book does not develop the full philosophical and theological consequences of the Church’s media experience either. The book aims to offer a useful enough middle ground that both camps can set aside their reservations and use it to extend their own lines of work.

Benjamin Peters: What is at stake in the title Eternity in the Ether. Unpack the title for us a bit.

Gavin Feller: Sure, the title has several layers.

Ether comes up a lot in 1920s discourse on radio as a new medium. Ether was often seen as a mysterious substance, even though it does really exist as folks understood it then. It was imagined to be the universal carrier of electromagnetic waves throughout the cosmos. As an invisible field always just outside of reach, the ether serves as a metaphor for asking questions about the stakes of eternity, future, and the collective vision for Latter-day Saints. How far does the ether extend? Where does eternity end? Hence, eternity in the ether.

But the title is also subtly sarcastic in drawing out a difference from the practical, cold hardwiring of real media infrastructures and substances. So, while the title signals a substance that doesn’t really exist, the content takes up the substance of what it takes to build, say, a successful radio or TV station.

In this tension between practical material substance and sweeping meaning, I also want the title to serve as a quiet homage to John Peters’ enormously generative book The Marvelous Clouds, which I admire. Finally, the title is also a nerdy autobiographical allusion for those who know that within the Book of Mormon there is a book of Ether that is written by the brother of Jared, and, of course, I have a brother named Jared, so I am the author of the book of Ether. I’m sure there are other layers of meaning for others to discover!

Benjamin Peters: Oh, that’s perfect. Can you, Gavin, help us think a bit more about the often under-acknowledged role women play in Mormon media history?

Gavin Feller: Yeah, I’d love to try. First of all, as all historians of the topic know, there are currently some documentary limits to what we can and cannot know due to archival walls the Church has put up around access to its own twentieth-century history: perhaps discovered diaries from women will lead the way here!

So, while I believe there may be treasure troves that would illuminate the role of women in LDS media history, I could not access many myself. Another obvious limitation is that, across mass media more generally and also within the Church, most stations are officially run by men. Church radio, TV, and early web presences: all manned new media, as it were.

What becomes more interesting is the role that women play in mediating public religious discourse about new media and changing technologies. In the 1950s Relief Society Magazine, for example, a remarkable number of women church leaders began writing about television in the home. Although the gender comparison is never a bright line, it might be possible to observe that women tended to panic less publicly and think more about the medium itself. Often in the mid century, prominent men would wring their hands about TV ushering in sex, drugs, and rock & roll into the home, while women publicly commented on the ways television organized and reorganized our shared social spaces, bringing people together in living rooms and elsewhere. Think loose trends, not bright lines here, of course. It is hard to find documentation for how LDS women contributed across all generations of new media, but women definitely expanded notions of community with the rise of online feminism well documented in chat forums and listservs in the eighties and nineties. A lot of their work expanded what today might be called intersectionalist identity positions: online, one could write, I’m Mormon and a feminist. I’m Mormon and gay. I’m Mormon and an evolutionary biologist, or whatever. These once-marginal identities gathered in online forums in the late eighties and early nineties, often thanks to women. Sunstone magazine has documented some of this, but much of it I found through oral histories with those who are still alive (a big thanks here to Joe Straubhaar, at UT-Austin, who pointed me toward these histories and connected me to important figures!). I hope that readers will not just follow my attempts to make sense of freshly overturned historical topsoil, but that future historians will dig deeper into the fresh historical topsoil this book digs up. May the role of women in Mormon media receive much more attention.

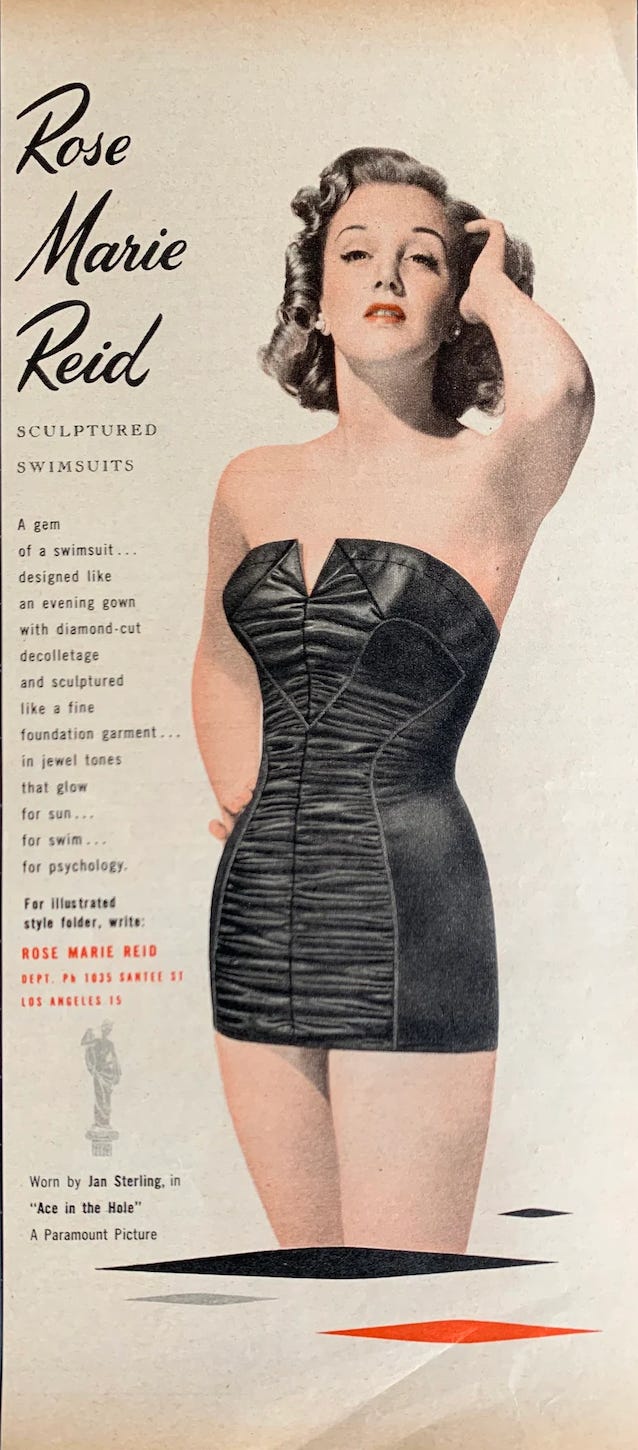

Benjamin Peters: To that point, your book raises a few really interesting specific case studies of women in Mormon media. For example, the case of Rose Marie Reid and her global swimsuit empire cannot be missed.

Gavin Feller: Rose Marie Reid is fascinating, so much so that I wrote a whole separate article about her. Reid may be the single most influential woman for me in twentieth-century Mormon media history, in particular her role as the founder of a global women’s swimsuit empire, an unrestrained evangelist for Mormonism, and a divorced mother in the mid-century US. Through the medium of the swimsuit, Reid’s story connects the quest for perfectionism to sexuality, modesty, and dress standards. There’s also a rich personal connection between Reid’s life as a mother and her role as a powerful business owner. Reid builds her swimsuit empire after divorcing her husband, raises her kids with the help of her mother, and simultaneously proclaims Mormonism–loudly and proudly–to everyone she meets. She tried to convert all of her swimsuit models, her business partners, and at the same time policed the appropriate male gaze in her swimsuit designs--all this from a woman cast, according to the cultural norms of the white midcentury America, as from a broken family. Television optics play into this rich intersection of embodiment, design, the gaze, commerce, and gendered religious culture. I tease out some of these threads in the book and my article has the fuller story for those interested.

Benjamin Peters: Thank you for the fascinating work. We will be sure to include all the links. There’s so much more we can and should be discussing here--the role of censorship and sacredness, how media shape community formation, and much else. What other kinds of work do you see Eternity in the Ether doing for Mormon media studies?

Gavin Feller: I would be delighted if the book, among many other less insider-baseball audiences, would help get religious scholarship a better seat at the cultural media studies tables. In particular, the book argues that religion is not that different from all the other socio-political institutions that cultural media scholars love to study. I posit that religion appears as a more concentrated form of a lot of American social and cultural ideals. By studying what is arguably the most American of all religions, we can bring those underlying assumptions and beliefs to the visible surface. American religion makes studying American culture, globally, a bit easier because its records are written down, documented explicitly. Despite relying on censorship-sacredness boundaries, religion is a relatively open culture: much more is recorded from the pulpit than in private boardrooms, as is often the case with other media companies. I hazard that everything outlined in Eternity in the Ether has parallels in other non-religious media organizations, whether they will admit it or not. Media conglomerates do not have scripture or doctrine, of course, but they certainly operate according to assumptions and fears, hopes and anxieties every time they encounter and have to make decisions about how to respond to media technical change. My hope is that religious media scholarship can help clarify the patterns of compromises and unintended consequences that attend all sorts of media companies and industries. I would be delighted if someone would treat, say, Walt Disney or Warner Media in a similar frame to how we now understand the LDS Church as a media organization, since it highlights how organizations negotiate doctrinal and community compromises. Religion is not as different as we would sometimes like to think.

Benjamin Peters: A nice motif: religion is more normal than it often appears in the rearview mirror of history. Weird media theory, meet normal religious media history! I am beginning to see more clearly how the analysis of many institutions operating on the background negotiation of doctrines and communities could benefit from a religiously lit lens for cultural analysis. Let's say you just stepped into an elevator with your 16-year-old, and they just learned that you wrote a book. You have, say, half a minute to tease them with anecdotes. What do you say?

Gavin Feller: The story of Mormon media is way more than the bumper sticker story that the ever-media-savvy President Gordon B Hickley was always a step ahead. In fact, it is usefully complicated. For example, did you know Mormon.com once hosted porn? And that KSL-TV once advertised alcohol and tobacco? How’s that?

If I had their attention, maybe here would be a bit more: in the middle of the 1990s, before the Church had learned to protect its online real estate, a bishop in Utah Valley stumbled upon mormon.com, found it full of porn, and then purchased it from the cybersquatting operator. The Church later realized the website’s value but not until a middle-rank faithful member bargained and privately haggled with the original site owner for the rights.

In the 1950s, the Church-owned KSL television station once advertised tobacco, which is expressly against the Church’s own doctrine, the Word of Wisdom. President J. Reuben Clark, who had a special fondness for the Word of Wisdom, was also President of the new Church television station, which found itself in debts the equivalent of millions of dollars today for all the studio equipment. In order to pay the bills, the Church had to accept nationally syndicated advertisers, including alcohol and tobacco giants. The book quotes an excerpt from a KSL-TV viewer who writes in to the station to complain that the church-run outlet is advertising alcohol and tobacco. How could my own church, they asked, try to convince my children to smoke and drink? Clark tried to negotiate with CBS, KSL’s network affiliate at the time, but the CBS executive Frank Stanton rejected Clarke’s requests, saying something like, I’m looking at this in a cold-blooded business way. National advertising could not be specialized yet. It was an all or nothing package. So Clark, an evangelist against alcohol and tobacco, had to make the argument to his own Church that the station has no choice but to advertise alcohol and tobacco. Clarke reasoned that if the Church was to enjoy the influence of a successful TV station in the long-term, and to maintain the respect KSL radio had earned, it had to accept this compromise in the short-term. It was an argument of sacrifices. I’m not saying the Church is hiding deep, dark media secrets; I’m saying compromise is how corporate media operate. As Marshall McLuhan said, media give, media take away. Compromises are not corruption; rather, media compel all to make compromises. No one is immune.

Benjamin Peters: A helpful and healthy lesson! The desire for doctrinal purity is regularly limited by the reality of living in the real world. The KSL compromise also depends on the particular affordances of mass media at the time. Unlike today, media corporations like CBS were unable to narrowcast and target specific advertisements for specific audiences, and thus neither were media organizations like the LDS Church. Maybe this is part of what you mean by weird media theory: namely, how appropriately weird mass media appear now from the vantage point of the second quintile of the twenty-first century pulsing with microtargeting and user data analytics. How about one last elevator anecdote: what did the “I word” in the 1990s Church office mean?

Gavin Feller: Sure. According to a Church historian Richard Turley, a major figure in many ways, people who worked for the church were often afraid of the internet in the mid 1990s, and some wouldn’t even use the word out loud. They called it the I word, like a curse word almost synonymous with pornography and pedophilia. You see here not only anxiety but the larger currents of the great internet sex panic in the late 1990s that would prompt Congress and international bodies to pass legislation limiting free speech online (the Telecommunications Act, the Child Online Protection Act). Lots of people were afraid of the internet.

Around the turn of the century, the organization’s mood shifted from fear to excitement: over the course of five to six years, the attitude in the Church moved from the internet as threat and perversion to an amazing means to advance genealogical work and connect people across space, time, culture, and generations. A quick index of the word internet in General Conference talks reflects this institutional shift from the internet as a parade of evils to the internet as the promising means for familysearch.com and outreach through mormon.org. A sea change.

Benjamin Peters: Terrific. You're providing a middle way that is not just between but beyond threat and moral panic, on the one hand, and tech friendly excitement, even boosterist promises, on the other. I see your drawing attention to how such cycles prompt observers to, again and again, acknowledge that neither the panics nor the promises are as bad or as good as they may first appear (or at least such expectations often end up off-target). Moreover, I see your reliable wisdom in pointing out that media observers can find solace and comfort in the predictability of such cycles. I hear you asking us to analytically zoom out and push pause. Speaking of the bigger picture, I remember 2012 being called the Mormon media moment. Do you have any insights into why your book arrives now, in 2023, alongside a small bookshelf of other works on Mormon media and technological change? What’s in the air, or the ether, as it were?

Gavin Feller: I don't know what's in the air right now, although, of course, the book came to be now only after many years of work. I started my PhD almost 10 years ago. And now we finally have the book. That’s not just the usual multiyear pathway of dissertation to book; that’s the result of the generational work of all those who paved the pathway to media and religion scholarship in the first place, like Stuart Hoover and Nabil Echchaibi at CU Boulder, and in the Mormon arena, Dan Stout, Sherry Baker, Joel Campbell, and others. They and many many others helped make religion and media into the robust subfield it is today; as graduate students, many of us were able to reap the fruits of their work to build interest, forums, and publications in the topic. There are also larger geopolitical religious movements spurring interest as well.

Benjamin Peters: I think your answer about the book’s timing parallels your approach to previous answers: It’s institutions!

In other words, I hear you saying scholarship does not tap some divine truth. You or I are not oracles that should be implicitly trusted (or a corruption that should be automatically distrusted). Your work, like so much else, should be trusted so far as it reflects the generations of work, institutions, interests, and communities whose labor and compromises it owes a debt to. So Mormon media offers a weird media theory, but again its media history appears not so weird: it reveals the usual work of institutions, people, and their complex relationships.

Gavin Feller: I am just glad I am able to do work that was meaningful and exciting to me and hopefully its audience as well. I am indebted to all the people, like you said, who make that kind of meaningful work possible.

Benjamin Peters: There’s much to appreciate in those who see in their high-profile accomplishments their debts to others. Could you recommend a few books for the listener who wants to learn more? They don’t have to do anything with the Mormon faith tradition. What are signal pieces that resonate with how you think about media?

Gavin Feller: Yeah. I recommend John Durham Peters’ The Marvelous Clouds, my favorite of his major works. It's a bit more intense on the philosophical side but it is worth every minute of your time. It will transform how you think about media, nature, animals, being, and environments. I would also recommend James W. Carey's Communication as Culture, a pioneering collected volume of essays that hugely influenced cultural media scholarship.

I would also recommend another classic from 1988, Carolyn Marvin's unmissable When Old Technologies Were New. My book, as even Marvin’s title suggests and as you suggested at the start, tries to re-envision mass media as new media.

Benjamin Peters: Fantastic recommendations. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Gavin Feller: What else? I’d be glad if academics would take up the book for the rigorous critique it needs. Maybe it’ll be fortunate enough to land reviews from scholars who will argue against my claims, maybe also knowing your and John’s special forum on Mormonism as a media religion. I am flattered that young researchers have been reaching out for advice, suggesting the work continues apace. I’d also be delighted to see more current Church employers find in the book an understanding of how media institutions make decisions. It’s a gift to watch others respond in different ways to the book.

Benjamin Peters: I love that you’re framing your book as a gift. The best gifts arrive without the expectation of reciprocity, and given that you’ve chosen to do things other than academia means you are not expecting the usual academic tit-for-tat economy of favors to balance in your favor. You’re giving it away.

Its argument calls us to predict reliable institutional compromises with media in our lives while still seeing, or at least seeking, greater meaning. Something as ambitious as Zion builds up from the mastery of mundane media techniques. Eternity in the Ether brings home that lesson with grace and insight. For me, your book does one thing more. As a lifelong church member who happens to be a media scholar, I was not prepared for how much of its material would be unfamiliar to me. Your book covers and makes sense of so much material that appears suddenly familiar but only after you say it. Familiarization of the uncanny and defamiliarization of the mundane are two sides of the same weird media theory coin. Media observers profit from their exchange rates! Without further ado, I’ll leave off with the invitation that your listeners become future readers by reading now the first few lines of your book:

“The story of new media is old, even predictable, but it is still unfamiliar. This story is a dramatic tale of bold claims and unfulfilled promises, but no one seems to read it. It is part of us because we have lived it over and over again, yet it is also far from us because we forget it over and over again. Once communication technologies are embedded into our daily lives, we rarely think about how they got there in the first place.”

Thank you, Gavin, for the fantastic conversation.

Gavin Feller: Thank you, Ben.

New Book Discussed: Gavin Feller, Eternity in the Ether: A Mormon Media History (University of Illinois Press, 2023)

Sources Mentioned: Mason Kamana Allred, Seeing Things (2023), Rosemary Avance, “The Medium is the Institution” (2018), Sherry Baker, “Mormon Media History Timeline: 1827-2007”, Jon Bialecki, Machines for Making Gods (2023), James W. Carey, Communication as Culture (1988), Gavin Feller, “Conceal, Enhance, Expose, Perfect: A Mid-Century Mormon Swimsuit Designer’s Feminine Bodily Discipline” (2018), Carolyn Marvin, When Old Technologies were New (1988), Benjamin and John Durham Peters, eds., Forum: Mormonism as Media (2018, ) John Durham Peters, The Marvelous Clouds (2015), and Speaking into the Air (1999), A few math rock riffs.

This interview transcript has been edited for clarity and content.

Wow. I know what my next book purchase will be -- indubitably. I like how you gents' styles worktogether and edify while giving variety of view. Thanks. Keep up the good work.