“What’s for dinner?”

For the first decade of our marriage, I was the one asking that question. Right after our wedding, my wife and I adopted the traditional household roles that our parents had modeled. Even when we were both students and without kids, my wife managed our tiny apartment, budgeted for groceries, and prepared the meals, bristling every time I sabotaged her plans for a salad by mindlessly eating an apple.

Today, it is my wife who asks that question, and I am the one strictly managing the ins and outs of our refrigerator drawers. After ten years of raising four girls, my wife entered graduate school and then full-time work as a speech pathologist. While she loved being able to welcome our kids off the bus, her long commute required that I organize my work life so that I could be the primary home parent. Suddenly, roles that once had seemed so fixed had been swapped. After years of knowing nothing about planning a weekly menu, I was now the one making trips to the grocery store with a photographic memory of our pantry’s contents, the one accounting for every piece of fruit that goes missing with a miserly eye.

There is a certain symmetry to our role reversal—but does that make our relationship equal? We considered this question one summer night as my wife’s cousin and husband explained their success with the book Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live). Written by the Harvard-trained lawyer Eve Rodsky, Fair Play helps couples balance out household responsibilities that have traditionally weighed most heavily on women. The book makes visible a home’s invisible labor by labeling every possible task—from the simple and routine (signing kids' permission slips and watering the plants) to the complex and fundamental (estate planning and calendar keeping)—on individual cards. Spouses then deal out the deck and trade tasks like baseball cards based on which responsibilities they value and prefer until both parties are satisfied.

My initial reaction to the book’s method was regret: if only we had considered such a plan years earlier, as I remembered with embarrassment my hapless inability—or unwillingness—to match my wife’s contributions around the house. But as my wife and I debriefed later that night, discussing whether to adopt the book’s approach, we both felt uneasy.

To be sure, we were inspired by the book’s vision of marriage as a union of equals. Fair Play, and the many books like it, insists that authentic romantic relationships must be grounded in equal regard for one another and their time. This regard is particularly important in an era when many wives have joined their husbands in the workforce while continuing to carry out the same household responsibilities that their mothers or grandmothers shouldered full-time. (Same-sex couples, as Kate Mangino points out in Equal Partners: Improving Gender Equality at Home, are also not immune to such discrepancies.) When the respective wages of a husband and wife approach parity, any disparity between their domestic contributions becomes that much more pronounced.

Thus, there is much about a method like Fair Play’s to applaud: by being intentional and realistic about household duties, limited hours, and personal preferences, it is home economics at its best, helping couples allocate their time and energy to maximize everyone’s peace and happiness.

Still, despite its appeal, my wife and I found ourselves hesitant to adopt such a method. For one, we wondered if pursuing equity in domestic tasks would leave us more frustrated than when we began. Alexis de Tocqueville, the French observer of nineteenth-century American society, noted that “When inequality is the common law of a society, the greatest inequalities do not strike the eye. When all is nearly level, the least inequalities offend it. This is why the desire for equality always becomes more insatiable as equality is greater.” As soon as some inequalities are rectified, others become visible. Pursuing equality often means never feeling satisfied with the results. When we declare that a condition is “equal,” we are really suggesting that it is “equal enough.” Equality is, ironically, relative.

Nowhere is this more true than in opposite-sex relationships, where the burdens of pregnancy and childbirth are unique to women. There are, as far as I can tell, no cards in the Fair Play stack for “Gestate Each Child for Nine Months” or “Deliver an Infant under Intense Physical Anguish,” nor is it clear what combination of tasks like “Teacher Communication” and “Bedtime Routine” might equitably compare.

But the deeper source of our uneasiness was concern that Fair Play’s calculating logic might spread to other aspects of our marriage. We wanted to be equals, yes—but we didn’t want to be equalized. That is, while we were both committed to making sure the other did not feel overburdened, we also worried that in the process of assigning and comparing each household task, a transactional spirit might redefine our relationship as a negotiated give-and-take.

To make sense of this response, it might be useful to consider the writings of the Danish philosopher and theologian Søren Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard’s brief but profound career was spent challenging the self-satisfied complacency that he believed was rampant both in Western philosophy and institutional Christianity. But he is, to put it mildly, a controversial voice in any discussion of marriage. In one of the most notorious breakups in philosophical history, Kierkegaard, convinced that he and his vocation were incompatible with domestic life, broke off his engagement to Regine Olsen, leaving her heartbroken and himself single until his premature death at forty-two. Not exactly a nineteenth-century John Gottman.

But what is useful about Kierkegaard here is how he defends the radical demands of love (demands he could not abide) against a rationalizing spirit. In the chapter “Our Duty to Be in the Debt of Love to Each Another” from his seminal Works of Love, Kierkegaard articulates how love is—or should be—categorically different from transactional relationships.

The fundamental distinction lies in the role of debt. “Usually,” Kierkegaard writes, “one says that the person who becomes loved comes into debt by being loved.” He takes the parent-child relationship as a primary example: because children are loved first by their parents, they are expected to reciprocate in turn. If I were to make my kids their favorite spaghetti dinner, and if they were to scarf it down without acknowledging the effort (totally hypothetical, I assure you), you might say that they failed to honor a debt of gratitude.

The problem with defining love in that way, Kierkegaard argues, is that such an approach to love “is all too reminiscent of an actual bookkeeping relationship—a bill is submitted and it must be paid.” Bookkeeping relationships are finite, with debts and payments that can be calculated, compared, and reconciled. But the essence of love is “infinitude, inexhaustibility, immeasurability.” For this reason, in love, the arrow of gratitude is flipped: when we love others, it is we who become indebted to them. In love, we take on an “infinite debt” that we never can—nor ever want—to fully remit.

Admittedly, Kierkegaard’s argument is bewildering (a common side effect of his work). He even admits that a “transformation of mind and thought is necessary in order merely to become aware of what the discussion is about.” To clarify, Kierkegaard offers a thought experiment: a lover performs a noble sacrifice but follows up by saying, “I have paid my debt.” Kierkegaard says that we would consider that lover to have spoken “unkindly, coldly, and harshly.” But now imagine a lover who performs the same sacrifice but says afterwards, “It is a joy hereby to repay a small part of the debt—in which, however, I still wish to remain.” “Would not this,” Kierkegaard asks, “be thinking in love?” This desire to always want to do more to honor your beloved, to remain obligated to them even after you bestow care and attention—this, Kierkegaard argues, is the core of love.

By now, the warning bells in your head should be ringing like mad. Isn’t Kierkegaard’s notion of “infinite debt” just another way for parents and spouses—mothers and wives especially—to be crippled by paralyzing guilt that they are never doing enough, that they should be devoting every one of their waking hours to their loved ones?

To mitigate that concern, we should first distinguish between a debt that is “completable” and one that is “fulfillable.” The debt of love is not completable the way a mortgage debt is—at no point can we compile enough acts of love to do justice to our beloved. Nonetheless, we honor, and thus fulfill, the demands of the debt whenever we perform an act of love, no matter how great or small. As the Kierkegaard scholar M. Jamie Ferreira writes, “I can never finish the task, but that does not mean that I can never fulfill the task.”

Furthermore, the debt that comes from loving another belongs, Kierkegaard claims, in the same category of debt that we owe to God for redeeming us from sin. In fact, we essentially roll over the debt of love into that greater one: “It is God who, so to speak, lovingly takes over the demand of love; by loving a person, one who loves comes into infinite debt—but also to God as guardian for the beloved.” And because the debt of love, like our debt to God, can never be completed, the answer to love’s infinite demands is not to simply give and give to exhaustion. Rather, we fulfill love’s debt moment by moment, delighted to find that love still calls us to give once again

How, then, might Kierkegaard’s theory apply to the modern quest for domestic equity? For one, Kierkegaard warns against comparing the love we have for others with their love for us. “In comparison,” he writes, “everything is lost.” By weighing our love on a scale, we reduce its transcendent potential to a finite resource that can be portioned out, thus removing love from its element and, like a fish removed from water, causing it to “droop and die.”

This reminder against comparison suggests that as we strive to balance household responsibilities, we have to be mindful not to exploit that balance to justify ourselves or to belittle our beloved. Pressed for additional help, it might be all too easy to respond, “I have just as many tasks as you do; figure it out.” Even going above and beyond one’s responsibilities can be self-serving: “Look at all the extra work I’m doing; why can’t you do the same?” Such comparisons warp the ideal of equality into a counterfeit of love. “The moment of comparison is a selfish moment,” Kierkegaard warns, “a moment which wants to be for itself.”

Kierkegaard’s argument also calls us to be mindful that, as we seek for parity, we do not become overly complacent. One advantage of a method like Fair Play’s is that it can help us feel confident that our contributions at home are equitable and appreciated. But if we take that satisfaction as a sign that we can brush our hands clean, that our work here is done, then we risk reducing our love to a series of tasks that can be checked off. The paradox of love’s infinite debt is that when we are “gripped by love,” to use Kierkegaard’s phrase, we will never fully feel like equal partners. For no matter how well we distribute household tasks, we will still desire to remain indebted to our beloved, to wish that we could do more. Even if we feel content in knowing that we are striving to do our part, we will never want to imagine ourselves so at ease as to believe that love’s debt has been absolved.

A couple can best achieve equality, then, not when they pursue it directly but when each commits themself to honor love’s infinite debt to the other. Equality thus comes in much the same way that, according to Elder Dieter F. Ucthdorf, obedience comes to those saved by grace: ”as a natural outgrowth of our endless love and gratitude.” Two people gripped by love will become equal because love will inspire them to strive for so much more. The limitation of Fair Play, such as it is, is not that its method is too idealistic; rather, it is not idealistic enough.

Dallin Lewis (Ph.D., University of Notre Dame) is an assistant professor of English in the Division of Humanities at Southern Virginia University.

News

Missed the Wayfare Issue 2 virtual launch party? Watch the recordings of the event here, and don’t miss the delightful video produced in Somerset, England by Timothy Farrant and his daughter Maysie. You can also find photos from the in-person party in Provo here.

Evangelical pastor Jeff McCullough has taken the last year to learn of the Latter-day Saint tradition, engage in interfaith dialogue, and build bridges across lines of difference. Exemplifying a refreshing spirit of good faith engagement and curiosity, his YouTube channel Hello Saints features dozens of videos exploring the religion, its history, and teachings.

Speaking at the 2023 Braver Angels National Convention, Elder Ahmad S. Corbitt reflected on the vital warnings embodied through the Book of Mormon against contention, division, and disunity. He encouraged cross-boundary friendship, peace and unity, and “respect for our sister churches and religions the world over.”

By Common Consent regular Michael Austin has continued to offer thought-provoking and faith-enriching engagements with the Come, Follow Me curriculum through the New Testament. His most recent pieces, “Ananias and Sapphira: History as Parable” and “The Conversions of Peter and Paul” are not to be missed!

The Church History Museum is showcasing a special 45-piece exhibit featuring the work of Minerva Teichert, one of the foremost Latter-day Saint artists of the 20th century. Titled “With This Covenant in My Heart: The Art and Faith of Minerva Teichert,” the exhibition will run from July 6, 2023 to August 3, 2024.

Finally, several volumes featuring previous proceedings of the Latter-day Saint Theology Seminar are now published and available for purchase. Volumes on Enos 1, Doctrine and Covenants 25, Mosiah 4, Mosiah 15, and Alma 32 can be found here.

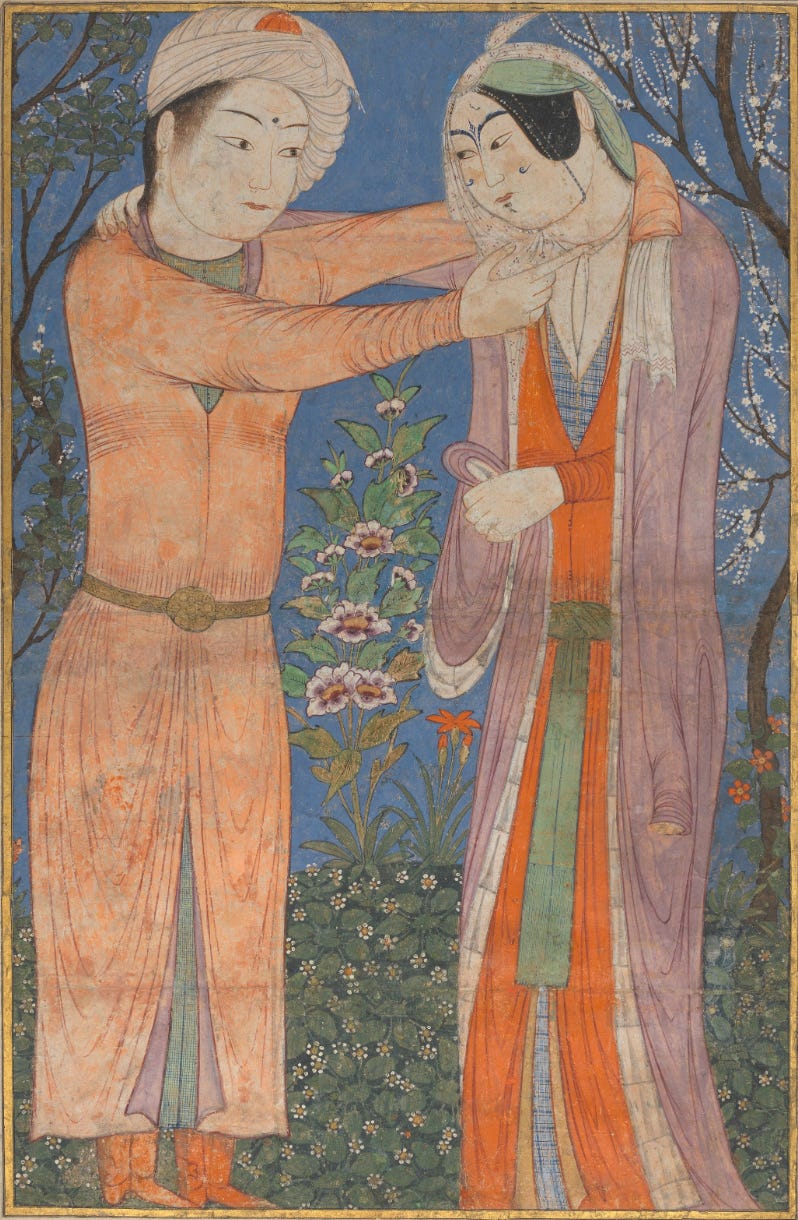

A good reminder of love's expansive and ultimately uncontainable nature.