Every fall, just as cool begins to creep into the air and the leaves begin to curl, the Stanford Latter-day Saint Student Association hosts their annual Convocation. We gather in Stanford’s Memorial Church, as saints and scholars, to grapple with the paradoxes of disciple-scholarship. Transcendent music washes over us, careening around the church’s stately pillars and from off its far-flung walls, and we sit and listen to students, faculty, and staff as they reflect, explore, ponder and arrive at tenuous conclusions.

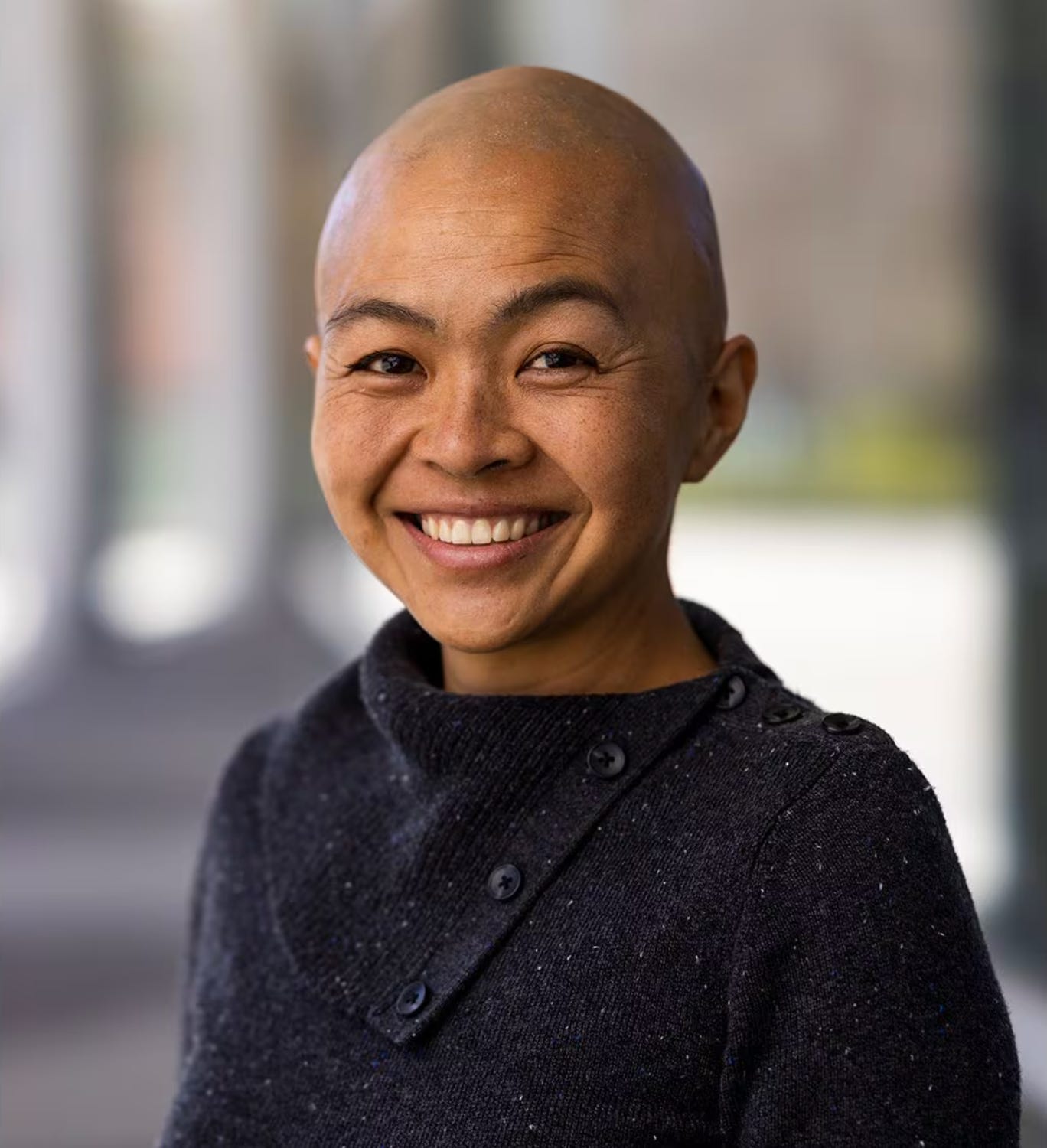

It was in this setting that I first met Melissa Inouye in the fall of 2022.

There was something joyfully incongruous about Melissa—all 5 foot and 90 pounds of her—standing at Memorial Church’s lectern, nearly invisible amidst such a cavernous space but for her gleaming bald pate. An impish smile occasionally danced across her face as she spoke. She struck me as some divine cross between Yoda and an owl: her cadence was sprightly, yet wise, her diction erudite, but never ponderous.

She was that rare writer, thinker, and speaker whose ideas were so much bigger than her ego that the latter never obstructed the former. She could talk about the hardest of questions and somehow approach them with equal measures of rigor and openness, candor and love.

And thus it was that, that evening, she spoke to us at length—as a bald Asian woman whose body must have already been riddled with cancer—about how to approach some of the most difficult aspects of our shared cultural and religious past.

Specifically, she compared Brigham Young’s racial animus to her own vomit. She observed that once when she was sick from chemotherapy, she vomited all over her kitchen table—and so her loving husband came, and tenderly cleaned up the sick. To not do so, she observed, would have been as illogical as it would have been callous. The mess was simply a fact amidst her life in this broken-down world. It was part of the reality of being in a place where something as terrible as cancer can ravage even the healthiest of bodies, where even the treatments that are supposed to make the cancer “better” can leave the person with symptoms that often seem worse than the disease.

Similarly, she said, she had confidence that Brigham Young (and others like him) now recognize that their racism was wrong—and that they look to us, their spiritual descendants, to be confident that they now know it was wrong. She was confident, she said, that those church leaders from days past need us to clean up the messes that racism has left behind, just as her husband cleaned up the mess when she was sick.

Melissa drawing this comparison speaks so much to what made her such a brilliant and unique voice in our cultural world. At first, the comparison seems a bit uncomfortable. For those of us who came of age dutifully singing “Follow the Prophet! Follow the Prophet! Follow the Prophet, he knows the wa-ay!” The prospect that something a past prophet said would need “cleaning up” may initially strike us unnerving. But once we push past that initial discomfort, we find that this comparison flows from love and an attempt to develop a holy historical empathy. And that is the goodness—and genius—that made Melissa who she was.

That goodness, intelligence, and depth are most especially on display in Melissa’s latest book—Sacred Struggle. Just like she did with the example about “cleaning up” the messy parts of our past (and a version of that address is contained as part of the book), what Melissa attempts in Sacred Struggle is a difficult thing indeed: without reservation or pause, and very much aware of the cancer that was already making her sick and that would eventually take her life, she looks at the messy, painful, sometimes punishing reality of life—both as a human and as a church member—and asks “Given all of this what are we to make of a gospel that claims to be about joy, and love, and redemption, and kindness, and even a plan of happiness?”

A lesser writer might have begun the quest, but would surely then have looked away. Confronted with such apparently insoluble—and inevitably, sometimes searingly, painful—paradoxes, most of us would take some route of easy escape. But Melissa somehow felt cause to lean in right when most of us would slink away. It is very much as she wrote in the book’s introduction:

I’m just one person. This is why for me, the most productive way to respond to heavy problems [in the church and in life] is to lean into my life as a latter-day saint. Such a life makes me part of a global community of people who share powerful connections. It situates me in a world in which I am surrounded by sisters and brothers, including not only the living but also those who went before. In today’s world of radical disintegration, silos, atomization, polarization, and big, complex problems, shared worldviews and orchestrated interconnectedness, organized religion’s two great strengths, are just what we need.”

With that confidence as backdrop, Melissa then leans into the world’s most vexing problems—including the most intractable theological problem of all: the reality of suffering in a world she chose to believe was governed and overseen by a loving creator. Indeed, now, today, in light of her passing, it is almost too tender and painful to go back and read an imagined conversation that she articulates in the book, a conversation she thought of having with her creator:

“God,” I whisper on days when I am too weary to weep and rage, “this is a terrible plan. You could take away this illness, but you don’t. You could fix our problems and right the world, but you don’t. You’re supposed to lead us in the right way, but you let us stumble and cause harm that cannot be undone. If you are good, and if you love us, why do you allow us to suffer or inflict suffering on others? If you healed a leper, or a man with palsy, or the woman who bled, why not me and those I love?”

One can easily imagine Melissa having this conversation in real time—Tevye-like—with a God she seems to have understood as an intuitive, even inescapable, part of her life. And yet as she answers these impossible questions, she simply will not accept easy answers. It might have been tempting to simply throw up her hands and say “well, it will all be ok in the end.” But that’s not where she lands—not really. That’s not to say she didn’t have faith in better times to come, or in a joy as transcendent as can be the pain of this life. But it is to say that her answer to the imponderable questions was something both truer and harder than what I wish it was.

Later in the same chapter she writes:

I have wrestled with God, seeking some epiphany that would make the problem of suffering feel right. I found there were no answers to the hurts and indignities of this world, for these things are not questions, but realities. Suffering never feels right. It feels like suffering. Like prayer, it is a form of work. […] Having experienced suffering, one develops power over it—not power to stop it, or take it away from someone you love, but to know sorrow’s face. Having experienced suffering, one receives power from it—the power to share others’ burdens and be humble, to see one’s own burdens and be kind.

Melissa helps us to come to understand that, in the holistic theology of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ, the point is not so much that suffering will end as it is that we are to find meaning while we suffer. The promise of Christianity, in Melissa’s formulation, is not so much that we will be delivered from the suffering of this world as that we will be taught by Jesus, and by those he sends to help us truly see, to look squarely into the world’s suffering and find love growing there, like flowers out of ashes. Indeed, she suggests that even if suffering could somehow be instantaneously erased from out of the cosmic sphere, that doing so wouldn’t be desirable because it is only through suffering that we can begin to love like God.

For my money, Sacred Struggle stands among the most important books published in the church over the last 25 years. It builds on the shoulders of works that came before it, including especially “A Latter-day Saint Theology of Suffering” by Francine Bennion, the writings of Eugene England, the theological work of David Paulsen and Blake Ostler, and the popular works of Fiona and Terryl Givens, especially The God Who Weeps. But because Melissa could approach her topics from such a personal and embodied perspective, she speaks with an immediacy and intimacy that those other writings sometimes lack. She makes no claim to be a systematic theologian, but her thinking sparkles, and, critically, she speaks as a minoritized member who is writing with the cancer that would take her life.

Perhaps because of this, Melissa developed a perspective wide enough to encompass Heavenly Parents who love us perfectly, yet allow us to suffer abominably; for fellow parishioners who could be vexing and sometimes even cruel, but that still bore the imprint of the divine; for a church that had patriarchy as one of its biggest “pachyderms,” but within which she still found spiritual succor; and for a prophet who could say things that were terribly racist and hurtful and yet still win her love and confidence that he was, nonetheless, eternally good.

In this expansive embrace of confounding paradox, Melissa charted the way forward for all of us as disciple-scholars, reminding us truth is made manifest by proving paradox and that Jesus taught most powerfully when he talked of the lost being found, the last being first, and the poor inheriting the Earth. She reminds us that there is no danger in thinking too much about restored Christianity, but only in thinking too little. And, above all, that even scholarship can be a form of discipleship, if we approach it with rigor—and love.

Sacred Struggle:Seeking Christ on the Path of Most Resistance was published in 2023.

Tyler Johnson is a Wayfare Senior Editor and an oncologist and Clinical Assistant Professor at Stanford University.

Thanks for the reminder of Melissa’s vomit analogy. I love that one.