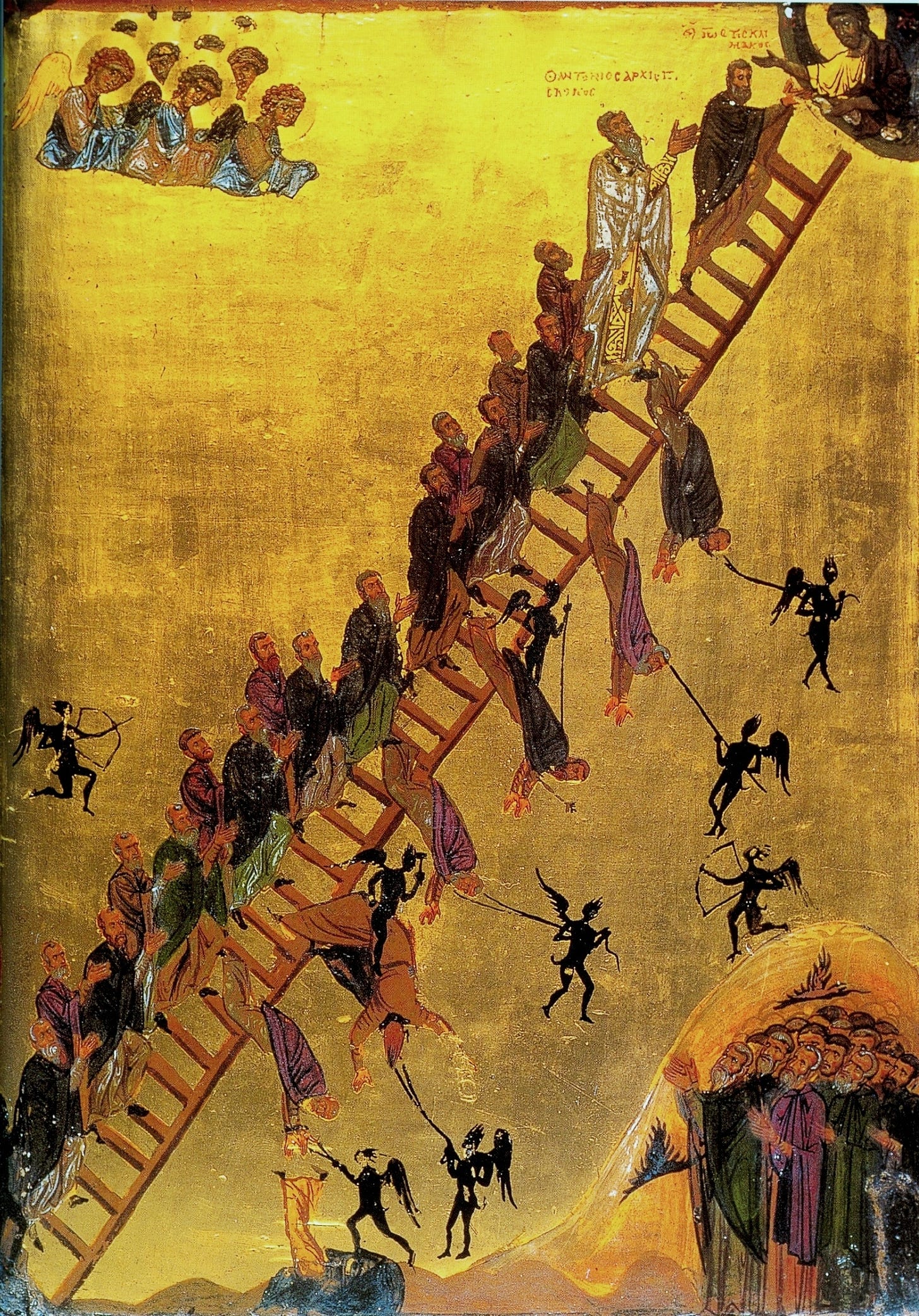

At dinner one recent evening, I asked a theologian and good friend of the church what ideas in our faith tradition had fed his interest. An Oxford scholar of early Christianity, he said it was hearing the ideas of the Cappadocian Fathers recapitulated in an unexpected nineteenth-century setting. The Cappadocians were three hugely influential fourth-century Christian thinkers (named after their origins in central Turkey)—Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Gregory of Nyssa. One of their shared themes focused on what scholars have called “the theology of ascent.” For all three, life is a process of ongoing sanctification, a becoming in some sense divine. In this view, the Father’s house consists of many “stages,” involving an eternal process through which we “ascend” toward a condition of ever-greater holiness. As one author describers their respective vision, “for Basil, theos [god] is simply a title which God bestows on the worthy. For Gregory of Nazianzus, theosis [divinization] is man's telos [final end] brought about by the deifying power of the Holy Spirit in baptism, and by the moral struggle in the ascetic life. For Gregory of Nyssa, a man becomes a god by imitating the characteristics of the divine nature, by participating in the divine attributes, and by modeling himself on the properties of the Godhead.”

Major voices of that era and earlier had similarly described mortality as a phase of spiritual education. Irenaeus (ca. 130-200) was sure that God organized all things from the beginning for “the bringing of man to perfection, for his edification, . . . that man might finally be brought to maturity at some future time.” He compared the first humans to children, learning through educative errors. A little later, Origen (185-253) read the Song of Solomon as an allegory showing “that the power of love is none other than that which leads the soul from earth to the lofty heights of heaven.” One must “pursue your spiritual journey through the wilderness, until you come to the well which the kings dug.” At the same time, the often legally-minded Tertullian (155-220) was reading the banishment from Eden the same way as Origen did. “For He did not forbid (our first parents) a taste of the miserable tree, from any apprehension that they would become gods; His prohibition was meant to prevent their dying after the transgression.”

Those were some of the voices my friend was hearing coming through this nineteenth- century religious tradition to which he had been introduced. Those ideas had lost their centrality in Western Christian thought many centuries ago. In Restoration teachings about a purposeful fall and humankind’s eternal progress, my friend was struck by the echoes he heard of the Cappadocians and their predecessors.

One might reasonably say that two basic models (with many variations) of human development have competed in Christian history. In one, life is a course of development, spiritual maturation, and transformation that God’s grace assists. The process is ongoing, eternal, developmental. In the other tradition, rooted in a model inaugurated in the fifth century and reinforced in the sixteenth, spiritual rebirth is largely tied to an “imputation of righteousness” in which grace consists.

Each version of the spiritual journey comes with its own variety of anxiety. The first seems to place a larger burden on the self—on agency, responsibility, accountability. The anxiety to which that challenge invites us was noted decades ago by Elder Neal Maxwell, and today is associated with the spiritual pathology of scrupulosity: “The first thing to be said of this feeling of inadequacy is that it is normal. There is no way the Church can honestly describe where we must yet go and what we must yet do without creating a sense of immense distance.” The second path has often led to its own anxieties—particularly those focused on the uncertainty as to whether one is the object of God’s grace, one of the elect whom he has chosen to infuse with his saving power. Such anxiety can be a powerful driver in the religious quest: it led to Luther’s spiritual innovations, John Wesley’s conversion, and Joseph Smith’s encounter in the Sacred Grove. But this anxiety can also be a detriment.

In any persistent, self-inclined anxiety—to the extent it consumes us—we are impeded in fulfilling the imperative that all we Christians share as aspiring disciples. And indeed, in seeking common ground with other Christians who are trying to be agents of earthly healing and transformation, it may be fruitful to recognize our common obstacles as well as common ends. This shared obstacle in particular was forcefully noted by the great theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. “Without freedom from anxiety man is so enmeshed in the vicious circle of egocentricity, so concerned about himself, that he cannot release himself for the adventure of love.”

Love as an “adventure” is a magnificent reminder of the risk and vulnerability that being part of an imperfect community requires. The followers of Jesus Christ in all traditions and times have learned that the adventure of love is not just impeded by egocentricity—it is also the way to a cure.

To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, first subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."

Thank you!