Latter-day Saints claim unique understanding of the Atonement of Jesus Christ thanks to the ongoing Restoration initiated through Joseph Smith. Yet we’re also influenced by Christian traditions that emphasize the very notions of equity and fairness repudiated by Jesus in the New Testament—which can lead to flawed perceptions of salvation. In this interview with Kurt Manwaring, Terryl Givens traces the history of atonement theology and explains why it matters to Latter-day Saints.

What is atonement theology?

Atonement theology is the attempt to understand how the death of Jesus Christ makes possible human salvation.

Anecdotally, what might a typical church member’s understanding of atonement look like?

There are a range of ways in which Latter-day Saints understand the death of Christ, but many (or most) are a form of substitutionary atonement—either penal substitution or what has been given the name of governmental theory of atonement.

Penal substitution (developed fully in the Reformation) is the idea that Justice demands a penalty and Jesus is punished in our stead.

The governmental theory is that a punishment or consequence must follow sin according to the law. God cannot forgive in the absence of that penalty, or he has in effect nullified the principle of moral law.

Some Latter-day Saints incline more toward a third view, moral influence theory: the belief that Christ’s submission to suffering and death was such an overwhelming display of compassionate sacrifice that love is “kindled in our hearts,” in the words of Abelard (12th c.) We are moved to repent and be reconciled to him as a result. The mechanism of Christ’s suffering is generally thought to be divine empathy in this case, rather than the infliction of a penalty.

Have you seen anything in general conference that suggests a new impetus for learning about atonement?

President Nelson has warned against objectifying the Atonement of Jesus Christ as “an amorphous entity” that is elevated above or exists apart from the love that motivated Christ’s life and sacrificial death.

Otherwise, I have heard no apostolic teaching that attempts to move us in a particular direction.

What is sin?

Sin is generally treated as a violation of the moral law. I think that is a good starting point for a definition.

What causes internal remorse when we sin?

Ideally, we experience remorse when we recognize in our sin a failure to love and we see the consequent hurt that our sin causes to others and to our relationships with God and our fellow humans.

Justice plays a big role in today’s meditations on atonement. Summarize what that looks like.

Different voices, even scriptural voices, depict justice in differing ways and with differing emphases or perspectives. Sometimes justice is reified as a kind of Platonic absolute to which even God is subject. And sometimes—as in some passages in the Book of Mormon—justice is another name for the law of restoration, according to which God promises that we shall receive according to our desires.

In other words, as I read those passages, justice is the principle by which the sanctity of moral agency is upheld. As in Section 88, we get what we desire, what we are willing to receive.

Repentance is the process by which we continually redirect and reshape those desires in holier ways.

If justice is largely a human attribute intended for mortal endeavors, why does it feel so intuitive?

Justice certainly takes many forms in human instinct and in human institutions. It’s important to recognize that historically, justice became institutionalized (as in the Code of Hammurabi)—not as a reflection of some perfect system of equity but as a way of controlling and eradicating the cycle of retribution.

If I can only exact an eye for an eye, that short-circuits what otherwise might spiral into a blood feud of increasing violence.

We sometimes conceal our lust for retribution under a veneer of more noble-sounding “justice.”

I think much of the attraction justice has for us is of Darwinian rather than divine influence. Certainly, our criminal justice system has often veered more toward retribution than rehabilitation or reformation.

In early Christianity, many leading voices were insistent that divine punishment was always purgative, never punitive. That distinction seems crucial to ascertaining the true motivation and quality of the justice being invoked.

Little children want the pie cut in equal shares because they want their “due.” The loving parent cuts the pie equally because he or she wants each child to get the maximum goodness possible.

Love and justice can define the same thing but from different points of view. And they are not always equally exalted points of view.

What does it mean to say that early Christians taught a “theology of ascent”?

If John’s witness is correct—that God is love—and if the love of God is to have any semantic continuity with the human experience of love, then we can say certain things about it. It would be rooted in the active promotion of the thriving of the other. And love, being expansively relational, would necessarily be costly, universal, and inexhaustible.

If that is true of God’s love, then all theories of creation that see human creation as an endeavor to glorify God’s own self have to be mistaken. That account is clearly more narcissistic than loving.

The objective of bringing human souls into fuller relationship with and similitude to God would have to be the real motive. Hence, the world would be in a Johannine understanding a school for souls, and we are on a ladder of ascent to God.

That is how the major voices of the first four centuries understood human purpose and God’s designs–including Irenaeus, Origen, and the Cappadocian Fathers (Gregory of Nyssa, Gregory Nazianzen, and Basil the Great). And they persistently used the language of “ascent,” “divinization,” and “theosis.”

Conceptions of original sin, human depravity, predestination, and special election—as well as later notions of imputed righteousness—were radically incompatible with this understanding of God’s love and were unheard of until the invention of what became Christian orthodoxy largely at the hand of Augustine.

The emphasis had been on an upward striving, a loving and transformative response to God’s love. The arrow rather abruptly reversed, and salvation came to be bestowed gratuitously, selectively, and unidirectionally as an act of grace.

How did Christ’s teachings radically challenge notions of human justice?

We have become largely anesthetized to the moral revolution that Christ introduced into human relationality—and much of it centered on his overthrow of our ideas, both innate and cultural, that revolve around equity and fairness (or justice).

In Christ’s teachings, early and late laborers receive the same wage. The sun shines equally on the just and the unjust. Sinners are forgiven and told to go their way and sin no more. The first shall be last. The Lord washes the feet of the servants. The human obsession with due proportion, zero-sum outcomes, and balanced scales melts away before the radiant cosmic asymmetry of love.

Why did it take centuries for a theology of ascent to give way to misunderstanding?

I’d rephrase the question. The question is why did Christianity so largely repudiate the revolution and return to so many structures that Jesus had repudiated.

The church became allied with—rather than a challenger to—worldly power structures in the fourth century. Only slightly earlier, creation ex nihilo replaced creation ex materia, giving emphasis to God’s power over his loving engagement with Creation.

Christ as the loving servant gave way in art and rhetoric to Christ Pantokrator (Christ the All Powerful). Atonement became fixated on repairing God’s wounded honor or status rather than humanity’s woundedness. State sanctioned violence against heretics, rather than loving persuasion, was institutionalized.

Clearly, we humans generally—and we Christians specifically—have found it irresistible to migrate back to those forms of power and “justice” that Jesus so emphatically overthrew when he washed the feet of his disciples.

Jesus had rooted the gospel in the forward momentum of life as educative, love as a dynamic force of change, and evolving relationality with God and fellow humans as central to the Christian message. Repentance and love were always reflections of a future orientation rich with possibility.

And yet, an irrepressible human need to balance past accounts—both Eve and Adam’s transgression and personal sins—lead to an emphasis on “satisfaction” as a concept pertaining to God’s honor rather than human healing.

Fast forward to today. Is the core of our interpretations closer to those taught by Christ or those which surfaced centuries later?

I think a major contribution of the Restoration was to repair and reconstitute the epic sweep of the human saga according to the earlier model.

Premortality (not universally but often taught in the first centuries), graduation to the educative experience of life, God as the weeping rather than impassible God, and Christ as architect and tutor rather than repairman of a catastrophe, along with the prospect of eternal progress and companionship with the Gods—those are largely unparalleled contributions to religious understanding.

Sin is not the catastrophe that dooms the human family, but a kind of collateral damage that was anticipated and provided for in the Messianic mission of incarnation.

Explain your theory that Christ’s life and teachings are meant to inspire us to live higher and holier lives, and help us remove the burden of sin.

I think it is enormously significant that the question the angel asks Nephi is not, do you understand the atonement? Rather, he asks, “knowest thou the condescension of God?”

Ways we speak about the atonement can have the effect of passing too quickly over the infinite love manifest in Christ’s willingness to subject himself to life—let alone death.

His name, Immanuel, is a reverent acknowledgement that his desire to suffer with us alone makes him worship-worthy.

We could not know the love of God through his death alone—many have given their life for a loved one. We need the entirety of John’s story of how he suffered hunger and thirst, fatigue and disappointment, tears of solidarity and tears of anguish.

The particularity of his love manifest across a spectrum of interactions is the clearest revelation we have of God’s love—and we lose the force of his incarnational impact when all of his birth, life, ministry, teachings, personality gets distilled into one pivotal moment of death.

If atonement is at-one-ment, reconciliation, then it is a process into which we must be drawn. An expansive understanding of incarnation offers multiple points of contact, influence, and transformation for being “drawn” to him.

Christ’s life is essential to that approach. What do we make of so many people who have lived without access to a record of His example?

One strength of Restoration teachings is that we have some good answers to that question that has haunted Christian history. One natural response to the quandary of such limited access to Christ and his teachings has been, “Right—we are part of the elect lucky few. Too bad for the rest.”

I think we have three healthier ways of thinking about it.

First, Latter-day Saints place particular weight on the process of embodiment itself. If a body is required for a fullness of joy, then the mere fact of embodiment fulfills a cardinal requirement of human progression toward God.

Second, along with some other Christians past and present, we have a sense of what has been called “the invisible church.” Countless individuals may be examples of what God called “holy men [and women]” unknown to us, who practiced love and emulated Christ though they knew him not by name.

And finally, the fact that evangelizing and sacramental work reaches to those dead as well as living extends the reach of Christ’s example beyond those formally catechized here.

What do we make of Restoration scripture that uses language like “merit”, “justice” and “advocate”?

Both scripture and the institutional church have emphasized the role of culture in shaping our understanding of the gospel. God speaks “after the manner of their language,” he uses language suited to time and place to “work upon our hearts,” and traditions of the fathers can influence us. The creedal tradition, said Joseph, is like an “iron yoke” that “fills the world with confusion.”

A church website says that “revelation is a process,” that God speaks to us “within our cultures and according to our understanding,” using “symbols and language” from that cultural moment.

If Christ came in the 21st century, would subsequent generations of believers compare him to a CEO? That’s not as ridiculous as it seems.

We invoke languages, metaphors, and analogies that are ready to hand. Paul used many varied ones: Christ as sacrifice, as ransom, as mediator. Those are not synonyms.

I don’t think any image or dictionary definition can do full justice to the mysteries of the kingdom and the solemnities of eternity.

President Nelson said the Restoration is a process, and I for one relish the quest to seek better and better language to celebrate it.

Did any verses initially feel like obstacles to your understanding of atonement?

Sometimes I think theology is all in the prepositions. I believe Christ died (and lived!) for me, but I think more is possibly embedded in that “for” than we have assumed.

What does it mean if I say that I sacrifice “for” my children? Suddenly the phrase may mean both more and less than I thought.

What has Jesus directly said about His atonement?

Nothing specifically, because the atonement becomes a freighted word only centuries later. Though he did say he would “draw” all men to him. And that one who loves gives his life for his friends.

Could you share a brief testimony about Christ and atonement?

I don’t know what transpired in Gethsemane, and I don’t know the cause or effect of his abandonment on the cross. But my hope that I will live again and that I can continue my journey to be like him is rooted in his life and death and resurrection, and that is enough for me to consider him the author and finisher of my faith.

Kurt Manwaring is the Editor-in-Chief of FromtheDesk.org, a Latter-day Saint history and religion blog, from which this interview originally appeared.

Terryl Givens is a senior research fellow at the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship at Brigham Young University. He is currently working on a history of Christianity which includes a lengthy chapter about the evolution of atonement theologies.

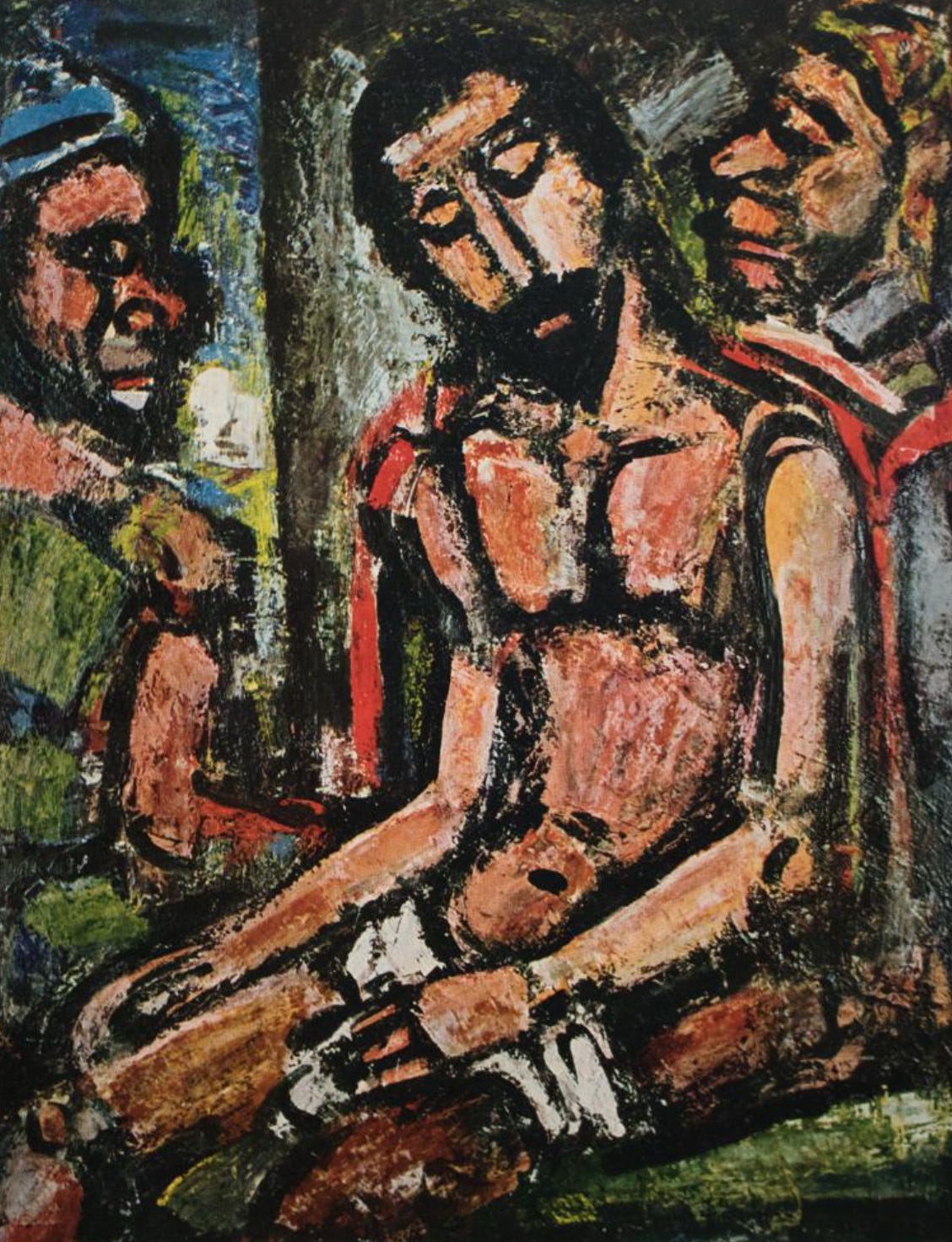

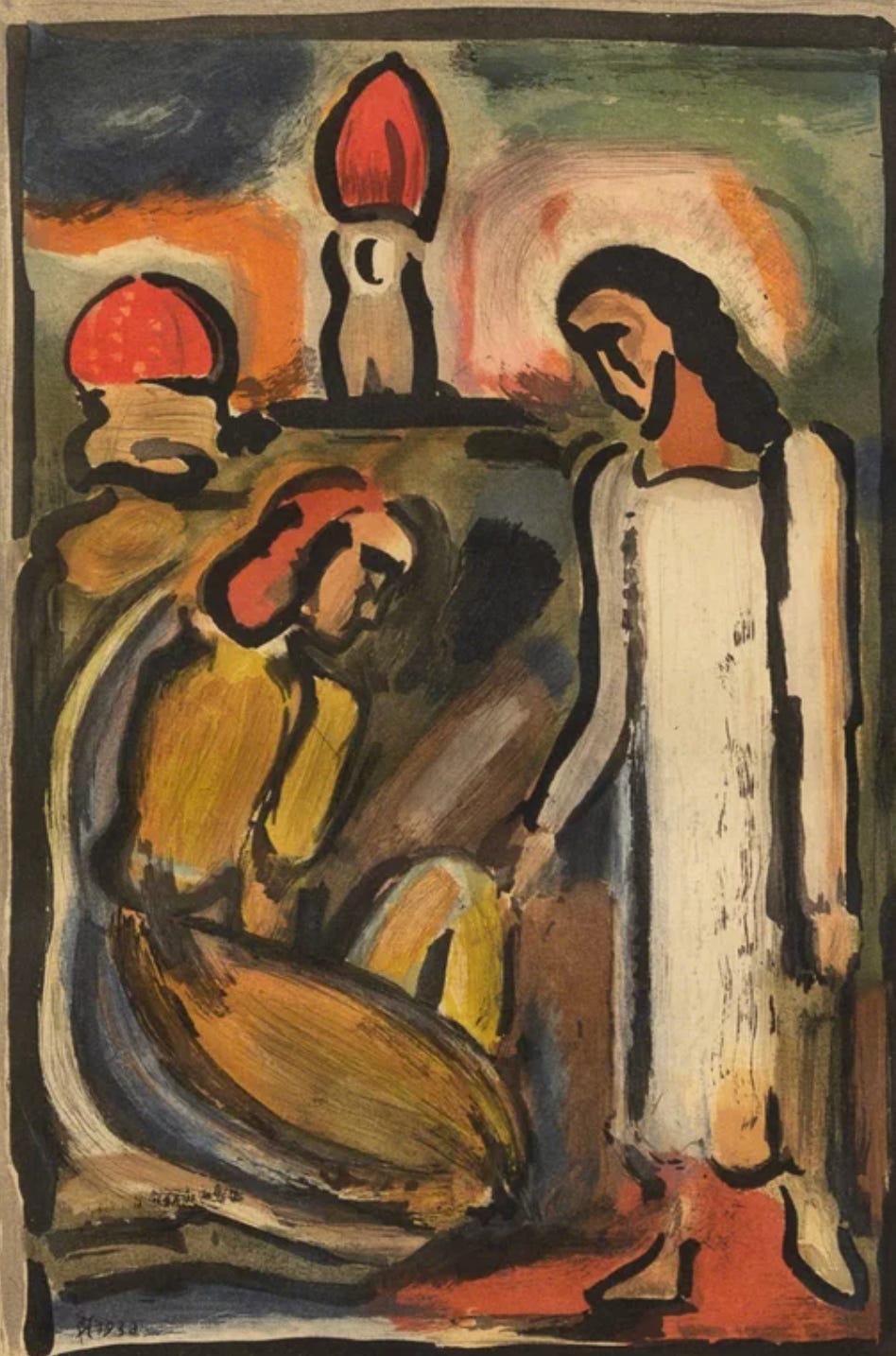

Art by Georges Rouault.

Beautiful. Inspiring. Terryl has such a beautiful way of expressing the essence of the gospel that speaks to my soul like few others. Thank you Terryl for your willingness to share your light and for Wayfare for publishing it with regularity. It feeds my soul.