Divine Vulnerability

Healing the Human Family

A few years ago, my wife and I started working with a therapist named Bruce, a self-effacing Buddhist master who is shinily bald and has wrinkled jowls that evoke the sleeves of a wizard. His eyes are clear and his gaze penetrating. When he laughs, there is nothing but laughter. He gets to the heart of the matter with the kindness of a bodhisattva and the fierceness of a samurai.

Gloria and I realized that there were some issues coming up in our marriage that we weren’t easily going to resolve on our own. Personally, I felt relief that I could share some of my frustrations with a third party. Hopefully, I thought, my wife would be willing to listen to me better if a trained professional assured her that what I was saying was important.

In our first session, after pleasantries and introductions, Bruce asked us the therapist’s equivalent to “what seems to be the problem?” I generously volunteered to explain that there was a real sore spot in our marriage. “There are times when I’m really passionate about something, and I want to share, but I notice my wife gets distracted a lot when I’m sharing. Sometimes it feels like she doesn’t really care.”

Bruce listened deeply, then reflected back, “I hear you saying that when you’re sharing something that’s really important to you, but then feel like your wife isn’t fully present with you, it’s a very disturbing experience.”

“Yes, exactly,” I said. “If I can’t share my excitement about life with my wife, then who can I share it with?” At this point, only ten minutes or so into the session, I felt a whole-body sense of self-satisfaction. I’d articulated my frustration fully and someone had finally understood it. Now for checkmate—Bruce will explain to Glo how important it is for a spouse to be a good listener, especially when your spouse is sharing something that means a lot to them.

Unexpectedly, Bruce put the question to me: “Thomas, I wonder if you’d be willing to give up the fantasy of a life free of disturbance.”

My jaw must have involuntarily swung wide open like the overhead storage bin on an airplane during severe turbulence. A dead silence followed. I was stupefied. After I returned to my senses, a profound clarity hit me with no further explanation needed: I realized I had unconsciously made it my wife’s responsibility to protect me from any disturbing experience in our relationship. I had told myself the fiction that if I was feeling disturbed, surely it meant that someone had done this to me, and that it was their job to make me feel better. In a single deft stroke, Bruce had cut through my drama and revealed a completely different way to be in my marriage: My wounds, my disturbances were my own, and nobody else was responsible for them. (Of course he wasn’t saying that when my vulnerabilities are triggered I can’t ask my loved ones for help. I can and I should. But if my go-to instinct is to blame people when I feel threatened, then I’m doomed to a life of constantly trying to control other people’s behavior.) I was never the same after that moment. My wife assures me our marriage hasn’t been the same either.

With the help of a highly skilled therapist, I was able to see that the everyday disturbance of not feeling valued didn’t start with my wife and therefore wasn’t likely to end with her either. That pain goes back to the foundations of human vulnerability itself.

From that moment on, I had an intention to stay curious each time I felt devalued. Rather than fixating on the story I had about how my wife needs to be a better listener, or how my friends ought to appreciate how helpful I am, I practiced staying in my body, staying with the very uncomfortable sensations that came up whenever I didn’t feel esteemed and valued. In doing this, I’ve learned at least two important lessons. First, when I feel disturbed, the temptation to avoid responsibility and blame my discomfort on others is almost overwhelming. Second, with practice I can actually learn to rest in my vulnerability, letting intense experiences rise and pass through my body like waves. After the intensity of the disturbance passes, I’m in a better position than ever to act with intelligent love, to do the most loving thing I can possibly do in the next moment.

The Developing Self

Bruce revealed to me how vulnerable I am in intimate relationships to not feeling esteemed. To fully appreciate the range of what he calls “core vulnerabilities,” it’s helpful to first understand the developmental territory of our most basic biological needs. By definition, to have needs is to be vulnerable.

From even before we’re born, we have a need for the basic conditions of warmth, nutrients, and adequate rest. In addition to crying when they’re too hot, too cold, hungry, or just plain tired, newborn babies are drawn to the voice, presence, and touch of their caregiver. From the very earliest stage of life, we start with a need for safety and security.

Just as foundational to our need for security is our drive to seek pleasure. In a sense, pleasure is a derivative of the conditions that ensure our safety and survival. For example, it’s incredibly pleasurable to get a good night’s sleep in a comfortable bed. It’s pleasurable to eat delicious food and to have a healthy body that’s free of any discomfort. From before the time we’re born, this need to seek pleasure and avoid pain is innate to our biology.

Just as early, our sense of self starts to form. There is now a “me,” and everything else that is “not me.” This emerging self is hungry for esteem and affection. From the first moments of our fledgling selfhood, we need to know that we’re wanted. To not be wanted or not belong is to face certain death. Most adults wouldn’t last too long left completely on their own in the wilderness. How much less an infant? Right at the heart of all human relationships is essentially a biological need to belong.

From about twelve to eighteen months in healthy development, we start to actively exercise our will and come into a sense of power. “I want that!” we yell from the top of our lungs. Wanting what we want, we’re very clever at working out the best ways to get it. Sometimes we unleash the all-out charm offensive, overcoming Mom or Dad with blunt-force cuteness. Other times we’ll deploy the meltdown technique. Not only do we learn to get what we want, we also learn to discern when we’ve met our match. We can tell when Mommy means business and when we might push a little harder for some extra screen time or a lollipop. In other words, we learn not only control, but submission.

We are born completely vulnerable to the conditions of mortality. And to the extent that our needs are not perfectly satisfied each time one arises, especially in early life, we will feel a disproportionate level of disturbance as we move into adulthood.

Core Vulnerabilities

When our foundational biological needs feel threatened in any way, when we experience privation of any kind, the body has evolved to respond with a certain measure of panic. It sends us highly intense signals that our very survival might be threatened. We feel disturbed to our core.

Our neighbors have a rescue dog, who likely spent some of his early days on the streets. He’s now a thriving adult dog with loving caregivers. But they still need to keep the supply of dog food well out of his reach, or he’ll get into the bag and literally gorge himself until he’s sick. He probably spent so long being hungry as a pup—feeling as though he was at the brink of death—that the hunger signals he gets now are especially intense, even exaggerated. In other words, he would do anything to avoid feeling hungry. To him, hunger pains mean imminent death. It’s irrational—he’s been food secure for many years now. All signs point to his next meal coming right on time. But deep in his canine bones he feels something very different: There is never enough.

To some extent, no matter how loving or perfect our homes were where we grew up, we all have an inner rescue dog. We all experienced privation on some level—this is the nature of embodied life—we are vulnerable by design.

We don’t have conscious memories of crying in our cribs as infants, the sting of hunger shooting lightning bolts of displeasure through us. In those moments, we didn’t have a mature mind that could reason that we’d likely be a little uncomfortable till Mom woke up. Rather, our direct experience was that we were on the brink of starving to death. The intelligence of our animal bodies produced an appropriately intense response, and as a result, we wailed with all our might to draw the caregiver close, to soothe the blaring sting in our world with the warm, fatty goodness of mother’s milk.

From early life, the natural man (i.e., instinctual self) forms memories of a world of lack. These are unconscious memories that are coded at the cellular level of the body. In our adulthood, these somatic impressions give rise to mental-emotional patterning that is primed for the experience of not enough. We see through the eyes of mortal scarcity, and everywhere we look we see deficit.

If I often felt a lack of security when I was young, I may be more prone to that experience later in life. I might eat more than I need to at a given sitting to avoid the vulnerability I feel when I’m hungry. Or if my fixation takes a different pathway, I might be stingy with my resources, feeling deep in my body that I don’t have enough to share with others.

Maybe I was deprived of pleasure or exposed to unbearable pain when I was too young to defend myself. Moving into adulthood, I might be addiction-prone, seeking pleasure and avoiding pain to an unreasonable degree. The ocean of suffering that seems to lie just beneath the thin surface of my everyday mind threatens to well up and drown me. So I err on the side of pleasure-seeking to the point that I’m almost totally unwilling to have a direct relationship with pain.

If I felt deprived of esteem growing up, I might be especially vulnerable to seeking out affection and approval. The more I go looking for approval, the hungrier I get for it. And social media exacerbates our vulnerability around esteem. It’s now easier than it has ever been to get immediate visual feedback on how people feel about me: How many views, how many likes did my last video get? Captivated by this substitute version of true esteem, we risk losing touch with our innate and divine value.

And then the need for power: To whatever extent I didn't have the experience of being powerful in early development, I might fixate on the need to be in control later in life. Maybe my parents struggled to provide a proper holding environment for me when I was young. I never felt quite like I could control my own space. Now when I feel a loss of control in adulthood, I panic and look to control things I have no business trying to control—my adult kids, the real estate market, people’s opinion of me.

I’ve emphasized the nurture side of vulnerability, but we’re each born with a biological predisposition to feeling certain vulnerabilities more than others. This is the classic nature/nurture dichotomy in psychology. Some of us may have more addictive personalities by nature and therefore react more intensely to the denial of a pleasure. Others of us who are more relational by temperament might be more vulnerable to a loss of esteem from others.

In any event, we have basic biological needs that are simultaneously our deepest vulnerabilities. We often react ineffectively to these mortal vulnerabilities in an attempt to escape our own suffering. Given this predicament, it would be convenient to have a language for this distinctly human psychology.

Energy Centers

In a brilliant move, Father Thomas Keating has integrated the developmental territory we just explored—core vulnerabilities and all—to life in the gospel. He realized that what Paul referred to as “lower nature” and the “natural man” can be understood not only theologically, but psychologically as well.

Father Keating describes this territory in terms of energy centers, a term he adopted from the work of the author Ken Keyes Jr. The original metaphor is vivid. In physics, the center of gravity is the point in a body where the mass is concentrated. This mass generates a gravitational pull. Gravitational fields can be weak or strong, depending on the mass of the body doing the pulling. We know from modern astronomy that gravitational fields can become so intense in the case of black holes that not even light can escape their field.

So it is with our core vulnerabilities. The signals of the body can be so intense when these vulnerabilities are triggered, it is as if they exert a gravitational pull on our higher nature. When the signals are intense enough, they completely consume our attention and energy in the vortex. We become fixated on the apparent emergency and routinely lose our capacity to make freer, wiser choices.

The energy centers in this sense are essentially one big energy suck. That is, when we’re caught in the instinctual drives of the natural man, we invest our time, attention, and resources to escape the vulnerability we’re already feeling in the body. We pursue symbols of security such as money and possessions in order to feel safe. We seek empty pleasures like scrolling on our devices and endless consumerism. We try to win the esteem of both ourselves and others by always being busy and constantly striving for accomplishment. We express a shallow sense of control by shouting over one another whenever we disagree. There is no end to these appetites. The more attention we feed these energy centers, the more massive they become. The more massive they become, the more difficult it is in each successive moment for us to escape their gravitational pull.

Because the body is developmentally foundational to our humanity, the heart and mind are especially vulnerable to its disturbances. Like any three-story building, if the ground floor has structural issues, the upstairs neighbors are going to feel it. Being aware of the activation of the energy centers helps us sense any tremors before they escalate into dangerous earthquakes on the upper floors. We learn to detect the very instant our basic needs feel threatened—when the shaking begins—and to seek more stable ground.

When we’re not alert to what’s happening in the body, before we know it, a disturbance has recruited energy from the mind and sent us into a flurry of anxious thoughts. The body then feeds on those thoughts and becomes even more disturbed. Or disturbance from the body seizes the heart and divides it with painful emotions. Those emotions then trigger similarly painful thoughts, thus agitating the body even more. In this way we generate our own private hell many times over in a single day.

As our awareness becomes more stable, however, we learn to soothe ourselves at the level of the body before these disturbances scatter the mind and divide the heart. How do we soothe ourselves? It is simple in concept but difficult to do in practice: We learn to be willing to feel what we’re actually feeling in the body and to trust the Ground of our being. That might sound abstract, but it is actually extremely concrete. Lehi embodies exactly this trust when he speaks to his son Jacob in the wilderness: “thou knowest the greatness of God; and he shall consecrate thine afflictions for thy gain” (2 Nephi 2:2). In more psychological language, as long as we are embodied beings, we are going to feel disturbance and signs of threat. But generally, the signs of threat aren’t indicating any real threat. We just feel threatened. We can trust the body’s process and let the tremors rise and pass without spinning elaborate dramas in the mind. When we’re in our private hell, we think: “This isn’t okay. I can’t be here. I need out.” When we’re in heaven, it’s just the opposite: “I am OK. This too is consecrated.” This is freedom.

Recall my unconscious rationalization in marriage therapy: If my wife would just pay attention to me how I want, when I want, my need for affection and esteem wouldn’t feel threatened, and I wouldn’t have to feel disturbed so often. In other words, rather than directly inhabit my vulnerability, I tried to control my wife’s behavior in an ongoing fantasy that one day I would be free of any disturbance.

The moment we feel intense sensations building up in our bodies, our instinct is to escape. In an effort to escape the reality of our embodied vulnerability, we often say things and do things that are harmful to ourselves and to others. We justify our actions because we feel at a deep level that if we don’t do something to escape, we’ll be overwhelmed with pain, or possibly harmed beyond repair. In a gospel context, we can understand this psychological process as the drive toward sin.

Sin

The Greek word in the New Testament that we translate as “sin” is hamartia. It implies “to miss the mark, to err.” But what mark are we missing when we sin? Where do we err in the vulnerability of these human bodies?

In a word, we risk worshiping the finite at the expense of the infinite. As human beings, we have basic needs that we can pursue endlessly in an attempt to avoid the basic fact of embodied vulnerability. There is nothing wrong with needing safety, pleasure, esteem, or power. In fact, we could say that these are all divine gifts we’re given to enjoy in human life. The problem is, we are all too prone to getting sucked into those black holes. The energy centers chant only one mantra: “This is good, but I’d give it all for a little more.” The appetite of our lower nature is insatiable. And because we can never get our fill at this level of reality, scarcity is the law of the land. In the Tao Te Ching it reads:

Fill your bowl to the brim and it will spill. Keep sharpening your knife and it will blunt. Chase after money and security and your heart will never unclench. Care about people’s approval and you will be their prisoner. Do your work, then step back. The only path to serenity.

What is purely irrational yet demonstrably true is that the more security we seek beyond a reasonable point, the more we feel like we don’t have enough security. When we idolatrize our basic needs, they become hollow gods who are impotent to satisfy the true hunger of our souls. We’re then left with the doomed task of trying to satisfy ourselves. In our worst moments, we'll justify any kind of behavior it takes to escape the specter of being swallowed alive by our core vulnerabilities. Sin in this sense is a vain but understandable attempt to avoid our deepest suffering.

In his formulation of original sin, St. Augustine duly notes our tendency to miss the mark, to act out. But he then goes a step too far in my opinion by imputing something corrupt about our humanity itself. With our new understanding of sin as a natural tendency to avoid vulnerability, we can easily imagine a new telling.

In a Latter-day Saint formulation of sin, we can start with a reverence for the physical body and acknowledgment that our biological vulnerability brings with it certain liabilities. But these are precisely the liabilities we’re given to work with in order to gain mastery over the physical realm. Vulnerability, in other words, is not a bug, it’s a feature. We have the opportunity as embodied beings to willingly accept more and more vulnerability—both individually and collectively. As we bear one another’s burdens, we imitate our embodied God who weeps, and we become more godlike ourselves in the process (Moses 7).

The word “vulnerable” comes from the Latin “vulnus” and literally means “wound.” Thus, it is not sin and a corrupt nature that we’ve inherited as human beings, but an Original Wound. By willingly embodying this Divine Vulnerability, we learn to descend below all things. To the extent that we’re willing to not only endure but embrace our personal Gethsemanes, we curtail sin’s capacity to tempt us. After all, if we’re willing to feel absolutely every experience that the Divine consecrates for our sanctification, what need is there to act out? What power does sin have to tempt us in the end? Christ is the living incarnation of this path.

Energy Centers in Scripture

There is a vivid depiction of the energy centers in Matthew 4, where Jesus goes out into the desert in prayer and fasting for forty days. It’s easy to skip to the end without letting the gravity of what is happening fully sink in. When I view this account through the lens of the energy centers, I see a clear path that Christ has shown us to further participate in our own theosis.

Whatever we personally take the Devil to be, we can say that he is cunning. He knows right where to hit us. There Jesus is, out in the wilderness, hungry, alone, and weakened. The Devil says to Him, "If you are the Son of God, tell these stones to become loaves of bread.” Remember, the prime directive of the body is to get comfortable and to stay comfortable. Few of us know how intense our disturbance would be if we fasted for days and weeks on end. This is energy center number one: safety, security. The Devil tempts and mocks him, as if to say: "You have all the power in the world. Why go hungry when you could have a bite of bread right now?" Jesus responds:

“People do not live by bread alone,but by every word that comes from the mouth of God.”

There is relative happiness, and there is happiness beyond conditions; the pleasure of having agreeable life circumstances versus the joy independent of circumstances altogether. Jesus is clear which master he serves and overcomes the first temptation.

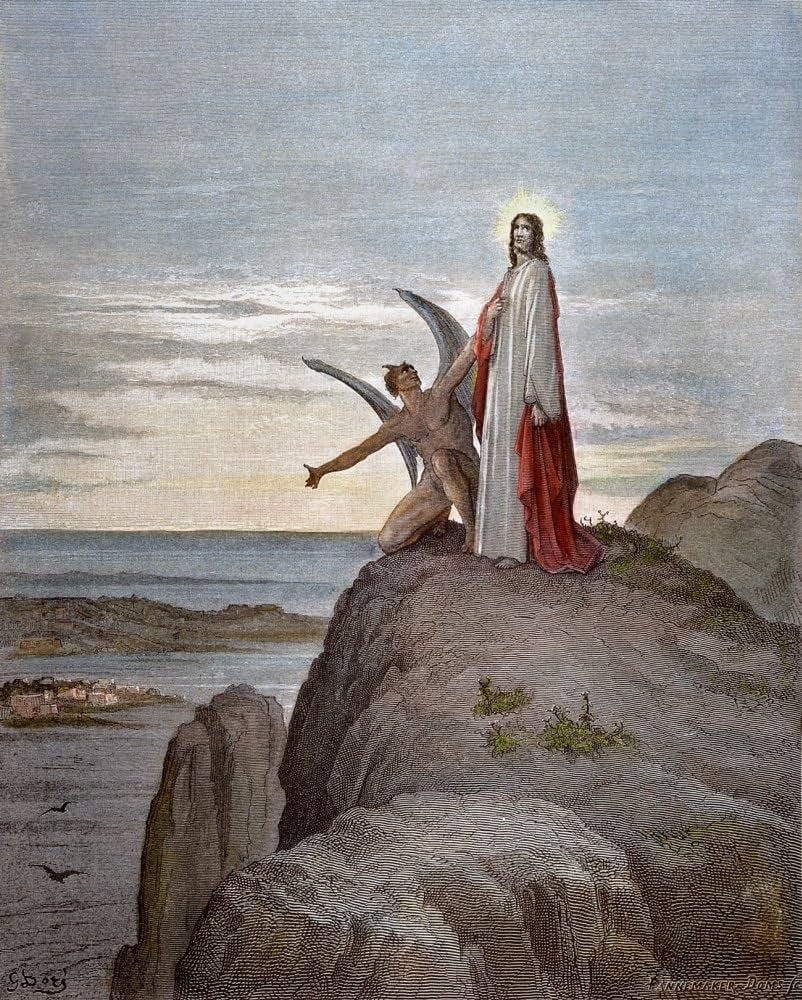

In the second temptation, the Devil takes Christ up to the top of the temple and says what amounts to, "If you're such a big shot, throw yourself off from this temple, and all of the angels, all of your pals will show up and they won't so much as let you stub your toe."

This clearly touches on the energy center of esteem and affection. The Devil plays on the very human need to feel important, to feel that we’ve got a posse at our back. Putting His trust in God alone, Jesus sees through this guile:

“You must not test the Lord thy God.”

In the third temptation, the Devil pulls out all the stops. He takes Jesus to the peak of a very high mountain and shows Him “all the kingdoms of the world and all their glory,” and basically says, you could have power and dominion over all things, if you first submit to me.

Jesus knows, however, that if He seeks power, the seeking will never end. His heart will never unclench.

“You must worship the Lord your God and serve only him.”

This account was written nearly two thousand years ago, yet the patterns remain timeless. Our core vulnerabilities are our greatest temptations. When our basic needs are threatened, we get intense signals from the body telling us there’s an emergency. From there, we have a strong tendency to freak out and rush to a short-term solution to escape what we’re feeling.

By overcoming each temptation, by confronting each core vulnerability of our humanity, Jesus chooses the only true happiness there is. How appropriate that His ministry should start right here in His moment of victory over the Devil:

Jesus came to Galilee, proclaiming Good News from God. “The time is ripe,” he said, “God’s realm is already so close to you. Turn towards it. Trust this Good News.”

In fact, the Kingdom is closer than close. When we are no longer afraid of our own vulnerability, when we are at-one with the joy and sorrow of our embodied humanity, we find an entirely new center of gravity in Divine Reality.

Though perhaps not as dramatic as the scriptural account, we are faced with similar temptations every day of our lives. To view the modern desert of temptation, look no further than the string of billboards lining the freeways. Almost without exception the messaging is designed to amplify our innate sense of lack. The ads tell us we would be happier if we made more money working from home, looked more beautiful by getting plastic surgery, had a drink while surrounded by beautiful people of influence, or went to the Bahamas to unplug.

How are we doing in our own desert? How often are we driven to satisfy the insatiable needs of the energy centers? Are you starting to see now that there is a part of you that will never feel safe and secure enough? A part of you that will never feel enough pleasure and avoid enough pain? The task is simple but difficult: Let your eye be single to God’s Glory. Let this sanctifying Light infuse the most vulnerable parts of yourself again and again. In exactly the most disturbing moments of your life, you can train yourself to open up, relax, and trust that something from beyond is making you holy.

Right Relationship With The Energy Centers

Life is actually disturbing us all the time. It's provoking us all the time at the level of our basic vulnerabilities. We think if we use more force, more cunning to get conditions back to a place where we don't feel so upset, then we'll finally be okay. In fact, this agenda is a program for misery. As long as we are unwilling to feel the vulnerability we’re already feeling, there will be no end to how much we struggle to escape our current experience. The energy centers will grow more massive and devour even more of our attention and energy as they do so.

As long as we are sensitive, embodied beings, we will feel disturbed on and off for the rest of our lives. This is what Bruce meant when he asked me with a Zen master’s sternness if I would be willing to give up my fantasy of a life free of disturbance. God wants us to get the message too. We are vulnerable in our humanity. We will be constantly tempted to blunt what we’re feeling by acting out and engaging in short-term strategies that make us feel a little better now but a lot worse in the long run. It’s sin by any other name.

Remember that in a sense, sin is a wrong view that denies Divine Reality and the abundance that is already right here. Sin is what feeds the energy centers and our chronic sense of lack. More than a punishable act, sin is a lost opportunity. Think of the last time you did something you would consider to be sinful, whether big or small. Were you not avoiding some uncomfortable experience in the body, doing something that you thought would bring you a little bit of relief in the moment, only to realize that acting out made things even worse than they were before?

The more we respond to the energy centers with a conviction that we must escape from what we’re feeling, the more we’ll come to believe that we aren’t capable of embracing our original wounds with love and acceptance. The more we act out from the energy centers, the more we reinforce the aspect of our humanity that feels alienated from God.

When we relate to the energy centers from a new place, however, they become a passageway into Grace. Every time we crash, every time we fall apart, we can stop and realize that this is an opportunity to be tender and fully embodied with this disturbance, with the most vulnerable parts of our humanity. As we do this, we discover exactly where we stand in need of healing. We feel our wounded humanity being redeemed.

Paul writes, "What a terrible predicament I am in. Who will free me from my slavery to this deadly lower nature? Thank God it has been done by Jesus Christ, the Lord. He has set me free." God uses time and mortality to create beings who can withstand Eternity. The Love, the Light, the sheer energy of Eternity is so immense, it takes time to get used to it. We have to get used to the intensity of true joy as well as the intensity of our disturbances. The energy centers show us precisely where we collapse. What feel like the most awful aspects of mortal life are actually Grace Absolute in disguise. The energy centers are like spiritual growth plates. They’re right where our soul is yearning for further expansion.

What’s more, when we learn to stay present to our own disturbance, we learn to stay present to all disturbance. In the end, it doesn’t matter if it feels like “my” disturbance or “your” disturbance. Disturbance is simply disturbance. It is a form of contracted Love, hidden in the shadows yet still seeking the Light.

We are Love’s means. Christ didn’t simply carry out the at-one-ment once and for all, he showed us how to at-one each moment of our lives through great acts of Love. When we are at-one with disturbance—the pain and vulnerability of our human-divinity—we redeem one another in Holy Presence. Bringing a greater measure of Love, a higher intensity of Light to disturbance, to the inclination towards sin, we heal the human family as Christ’s true body.

Thomas Wirthlin McConkie is an author, developmental researcher and meditation teacher. He is the founder of Lower Lights School of Wisdom. He has been practicing for over 25 years in the traditions of Sufism, Buddhism and Christian contemplation, among others.

This essay is an excerpt from Thomas’s new book At-One-Ment, published by Faith Matters.

Thank you, Thomas. This has lead me to a much deeper understanding of and access to the repentance process. Seeing myself through these inborn vulnerabilities allows me to put down my defensive walls and embrace every chance that comes to learn from things that disturb me or that rob me of living in my peaceful (boring... growth-defying) status quo. This just makes so much sense to me!

Wow, honestly I’m speechless. I need to just sit with this for a while. I’m pretty sure this is the climax to the lesson God is trying to drive home.