Dialogue Across Difference

The Last Supper

As a filmmaker I’ve been able to talk with some pretty remarkable people and tell their stories. We screened one of our films in Boston over a year ago. The theater was filled. People there included past and current presidents of Planned Parenthood. A few rows back was the president of the largest pro-life organization in Massachusetts. Women who advised the Pope were in attendance. People who had seen friends gunned down in abortion clinic shootings attended. There were pro-choice and pro-life activists—people who had protested and been arrested. These were people who really cared and desperately disagreed personally, politically, and publicly.

They had come to see our film, which at that time was called The Abortion Talks—but has since been renamed The Basement Talks. This was almost certainly the most politically diverse screening of a film about abortion, and may well have been one of the most politically diverse screenings of any film in history.

This story started with two murders, and the court case that followed. The defense attorney talks about how the case became a media circus. We see the pro-choice and pro-life movements trying to control optics, jockeying for publicity, and putting their spin on the story. But the case is never resolved because the man who murdered the people at the abortion clinic, John Salvi, was murdered in prison. That's the story everyone saw. It’s a tragic story, a sensationalized story.

But there's another, quieter story, one that took place in a basement. Three pro-choice and three pro-life leaders began meeting secretly. I mean nobody knew about them. Fran Hogan, one of the pro-life women, snuck off to these mysterious meetings enough times that her secretary thought she was having an affair. These women met for six years, and recorded a total of 150 hours of conversation.

Let me tell you about some of these women.

Nicki Gamble was the president of Planned Parenthood League of Massachusetts. She opened the first Abortion Clinic in Massachusetts. She grew the organization from an operating budget of 200K to multiples of millions. Today, there’s an abortion clinic in downtown Boston named after her. But do you know what she says was the most important experience of her life? It was meeting with these six women.

Another woman was Barbara Thorp. As a young adult, she was arrested for protesting the Vietnam war. After the war ended, her anti-war/pro-life sentiments were funneled into the pro-life movement. She became the first ever layperson over the pro-life office of the archdiocese in Boston. Later, she was appointed head of victim outreach after the spotlight article shed light on pedophilia in the Catholic church. After that, she was appointed by the state of Massachusetts to lead victim outreach following the Boston Marathon bombing.

And yet one of the most profound moments of her life was eating cake. She described the moment to us. The six women had gone out to eat together. They’d finished the meal and the waiter asked if anyone wanted dessert. She says everyone wanted dessert but no one wanted to say they wanted dessert. But somehow, a dessert was ordered, and the waiter brought out a bunch of spoons. She describes partaking of that sweetness together as a sacred experience.

Perhaps there are few things more Christian than sharing bread, in this case, highly sweetened bread. Two thousand years ago, there was a similar event. That time it was a gathering of men, and instead of cake, it was flatbread, broken, shared. And some wine, drunk. And of course the people. Friends, Jesus calls them. Traditionally, the seder was a family event. And this was the creation of a new family. The family of Jesus. His church.

And they eat together. And then Jesus washes their feet. And Peter protests. Don’t wash my feet, he says. Because what else can you say when divinity not only sees your dirtiness, but starts to wash it away. And then Jesus gives his first commandment to this new family. The base layer of code for what would become his church. The bedrock upon which his followers would build. He tells his disciples to continue these two acts. To break bread together. And to wash each other's feet.

And while we have partially institutionalized the breaking of bread, the washing of feet has remained almost entirely in the realm of our personal discipleship. And so let’s consider our involvement in Christ’s church. Are we performing this most basic level of discipleship? Who do we share bread with? Whose feet do we wash?

As we consider this most important question, we no doubt will come to a hard decision: where do we draw the line? Who do we welcome in? Whose feet do we wash? And who do we cut out? Do we call some people to repentance first? Who really is the sacrament for? Is it only for active members who are on time to church? The institutional church leaders will decide church policy. But as members, we must also consider where we draw our lines, because Jesus does not draw a line for us. Instead, he simply says to do as I have done.

And who was at his table? The man who would betray him, had betrayed him already in his heart—yes, he was there. The man who would deny him three times—yes, he was there. The man who would not believe his resurrection? Yes, he was there too. The family of Jesus, his disciples, those that would become apostles. The ones who would build a church, tell his stories, create a movement. People who would disagree passionately, dramatically, constantly. And yet they met together, and broke bread, and washed feet. And somehow, they persisted. Against all odds, they created a movement that overtook Rome. It spread faster and more completely across the world than any other religion. And how has it survived and persisted in the millenia since? How has it moved from culture to culture, from continent to continent, from race to race?

I think the roots of its success can be traced to its origin. Which in a real way was the sharing of a meal, the last supper, and two traditions Jesus started. But what is so powerful about sharing a meal, and washing some feet? And why eat with people who sin, or who are wrong, or who look or think differently? People who will betray you? People who will deny you to the world. And worse, people who will deny your God? Why include them in these sacraments?

How far can this charity go? Didn’t Jesus also say there would be wolves in sheep’s clothing? Aren’t we to protect the flock?

Yes. But I don’t think we do this best by being on the lookout for wolves we can exclude, or call out, or cut off. This was the approach of Captain Moroni, who was so infuriated with the political beliefs of Amalickiah that he provoked a mob to chase Amalickiah out of the land. They banished him. And to what end? Amalickiah joined the Lamanites and raised armies and became much more dangerous than he’d ever been as a Nephite. That is the problem with rage. That is the problem with anger. Feuds grow; they do not resolve easily.

I think Jesus's plan was more subversive and more effective. To protect the flock, Jesus gave us two rituals. Eat together. Wash each other’s feet. Because this is how we turn enemies into friends. This is how we preserve who we are without shrinking into unholy orthodoxy. This is how we continue to grow in particularly turbulent times. This is how we survive persecution. This is how we continue to remain relevant. Because we have these traditions and these rituals at our very base. Traditions that enfold people, that build bonds of belonging. They heal wounds, they end feuds, they temper rage, they ward off jealousy. They are traditions that don’t shrink from difference and are not scared by a few fangs.

So how does this work? Let’s look at the women of The Abortion Talks and what they were able to accomplish together. And actually, what the women didn’t accomplish is perhaps as important as what they did. They did not come to common ground. They did not come to an agreement. They did not change each other's minds. But they did change their opinions about each other. And this in turn changed everything. It changed how they spoke to the media. In fact, a random journalist in Boston who had no clue that these conversations were happening, wrote an article saying that opinions on abortion had not changed, but the rhetoric around the issue had. And what was behind that change? Six women breaking bread together.

Now imagine if that had happened with Moroni and Amalekiah. Would enemies be made friends? Would history have changed? Would thousands of lives have been saved? Perhaps, perhaps not. But let us not underestimate the power of our founding rituals.

And while they are powerful, they are not always easily done because, when you do this, you are not just gaining a friend but losing an enemy. Madline, one of the women in those basement conversations, characterized it as an internal battle. Because she felt that what the pro-choice women were doing was evil. But after spending so much time with them, she couldn’t help but feel that they were well intentioned. And that was hard for her. Yet the struggle blessed her life. Later, when a member of her organization approached her to evaluate an op-ed, Madeline refused to publish it because it mis-represented the pro-choice position.

This work takes courage. You will realize that your enemy is not only like you in many of the best ways, but that you are like them in many of the worst. You both take baths and yet you both have dirty feet. This, I believe, is Jesus’s brilliant method for purifying his church and protecting his flock. It might not kill wolves, but it makes them less dangerous. Saint Francies of Assisi is said to have tempered the child-eating wolf of Gubbio by feeding him, and holding his paw.

The betrayer, the denier, the disbeliever, these were all wolves invited to Jesus’s supper. And he washed their feet. And their history has been written, and somehow their crimes, their failures, their sins were transformed. Somehow, each of them, in their own way, furthered Jesus’s work. You see, even his enemies advance his work. I think that can be true of our enemies, if we can accurately call them that.

Again, the women of The Abortion Talks are an example. They reported feeling more comfortable, more confident, and more convinced of their opinions after six years of dialogue. And they spent most of that time talking about the very issues they disagreed about. And they called this a gift. They reported understanding themselves better as well as understanding the other side better. They reported being better leaders in their respective organizations. Each of them furthered their work.

That is why we must break bread with others. And we must wash feet, particularly the feet of those we disagree with. We must do this for ourselves and our own sake. It will reveal ourselves to ourselves. It will keep us humble, meek, and pure in heart. This is how we inherit the earth. Breaking bread and washing feet are professions of peacemakers. This is how we become children of God. This is how we become members of his church.

And this is how we maintain his peaceable kingdom even in an increasingly polarized world. The polarization could grow exponentially as we arrive at another election. We are likely to feel strong emotions ourselves and witness dramatic scenes of conflict, anger, and rage. But our congregations must transcend these tendencies. This is critical for our survival as a church and perhaps even our nation. It was once predicted that the day will come when the constitution will hang by a thread and members of the church will preserve it. Some have imagined the fulfillment of this prophecy as dramatic, warlike scenarios, with another Mormon Battalion arriving on horseback, like Rhoherim, in the nick of time, saving the capitol. But I think it is much more likely that this is how we do it: by breaking bread and washing feet.

The last supper is the secret sauce to the survival of Christianity and perhaps our nation. It’s the key to our ability to turn enemies into friends, an outward-reaching, inward-growing motion. It moved the church from Jews to Gentiles. It crossed oceans. This is how we lengthen the stakes of zion. We do it by never stopping, never relenting, never failing to practice our founding rituals: breaking bread and washing feet.

It might not seem dramatic or even heroic. But as the women of The Abortion Talks found out, it might be the most important thing you will ever do. I witnessed the power of this work as the final scene ended, and the credits rolled in Boston over a year ago. Remember who was there? As the curtains fell, the entire audience stood and cheered. Pro-choice and pro-life leaders, activists, and pundits clapped together. They cheered and wept. This group was united for the first time in a long time. And that was something to see. A profound glimpse into what is possible.

And if you do this work, like these women, you will realize that your enemies are rarely to be feared. And for your salvation and for your church’s and country’s preservation, you must meet them as the full-bodied, well-intentioned people they are. These are the people who will correct your assumptions. These are the people who will see your blind spots. These are the people who will expose yourself to yourself. What you thought was a curse might become your greatest gift.

This is not to say there is no risk. But our enemies are our brothers and sisters. They are not just to be overcome, but to be wrestled with. And they will dominate you at times. And you will be tempted to break the connection. But before you do, please know that this church is held together by these connections. This supper has been happening for dispensations. It’s been practiced across the world, in every country, on every continent. It happens in upper rooms and in basements. It’s often not seen. Sometimes it’s kept secret. But this is how we’ve persisted. This is how we’ve endured. This is how we will continue into the future. This is our bedrock and our salvation.

Joshua Sabey is an award-winning director, producer, and writer. His latest documentary won best documentary at the prestigious Boston Film Festival where it screened opening night. His work has been featured in multiple major news sources including The Christian Science Monitor, The Fulcrum, WBUR, and more.

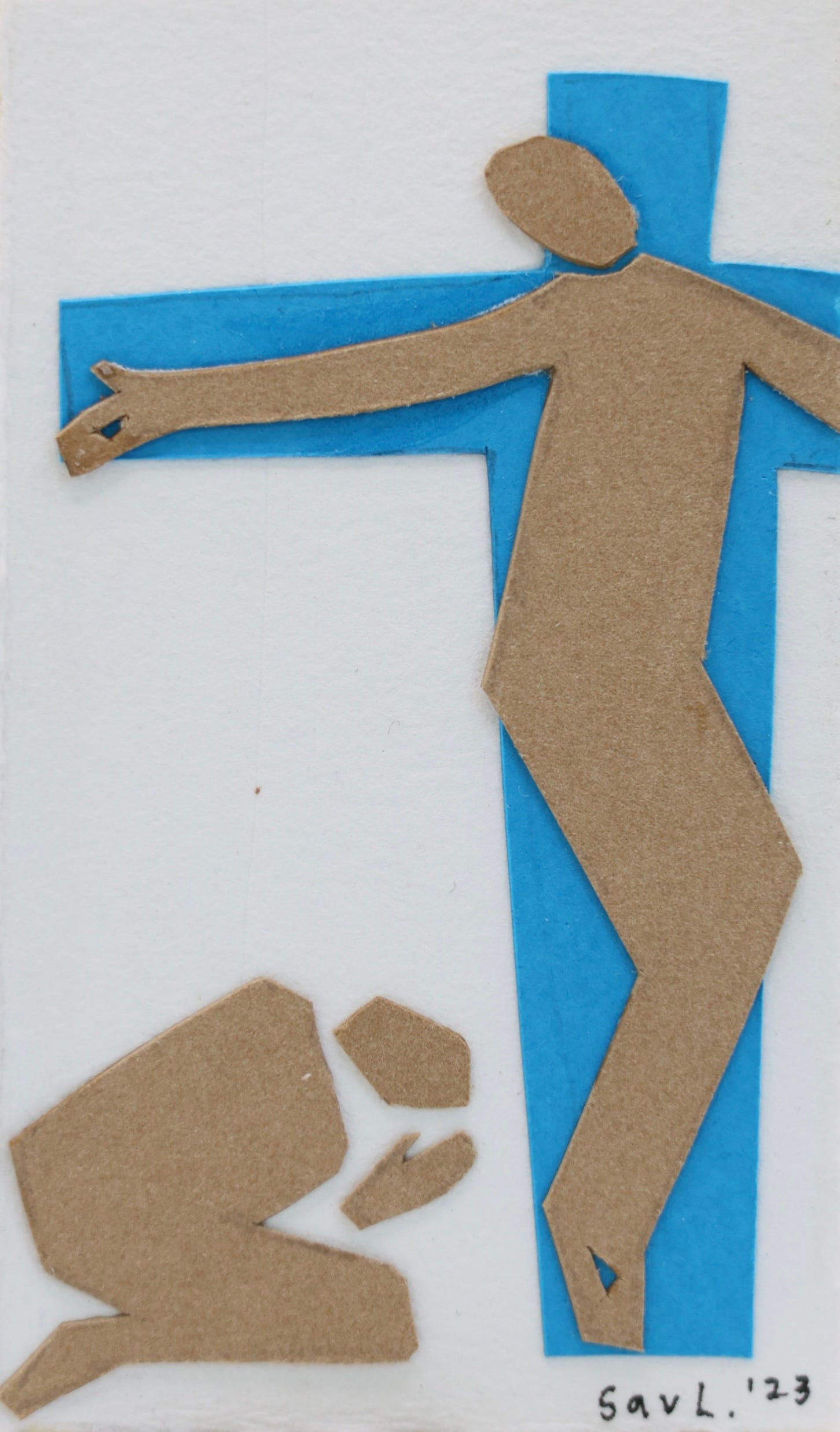

Art by Savannah Liddicoat.