Deep Unmet Needs

“Jesus saw sin as wrong but also was able to see sin as springing from deep and unmet needs on the part of the sinner.” —Spencer W. Kimball

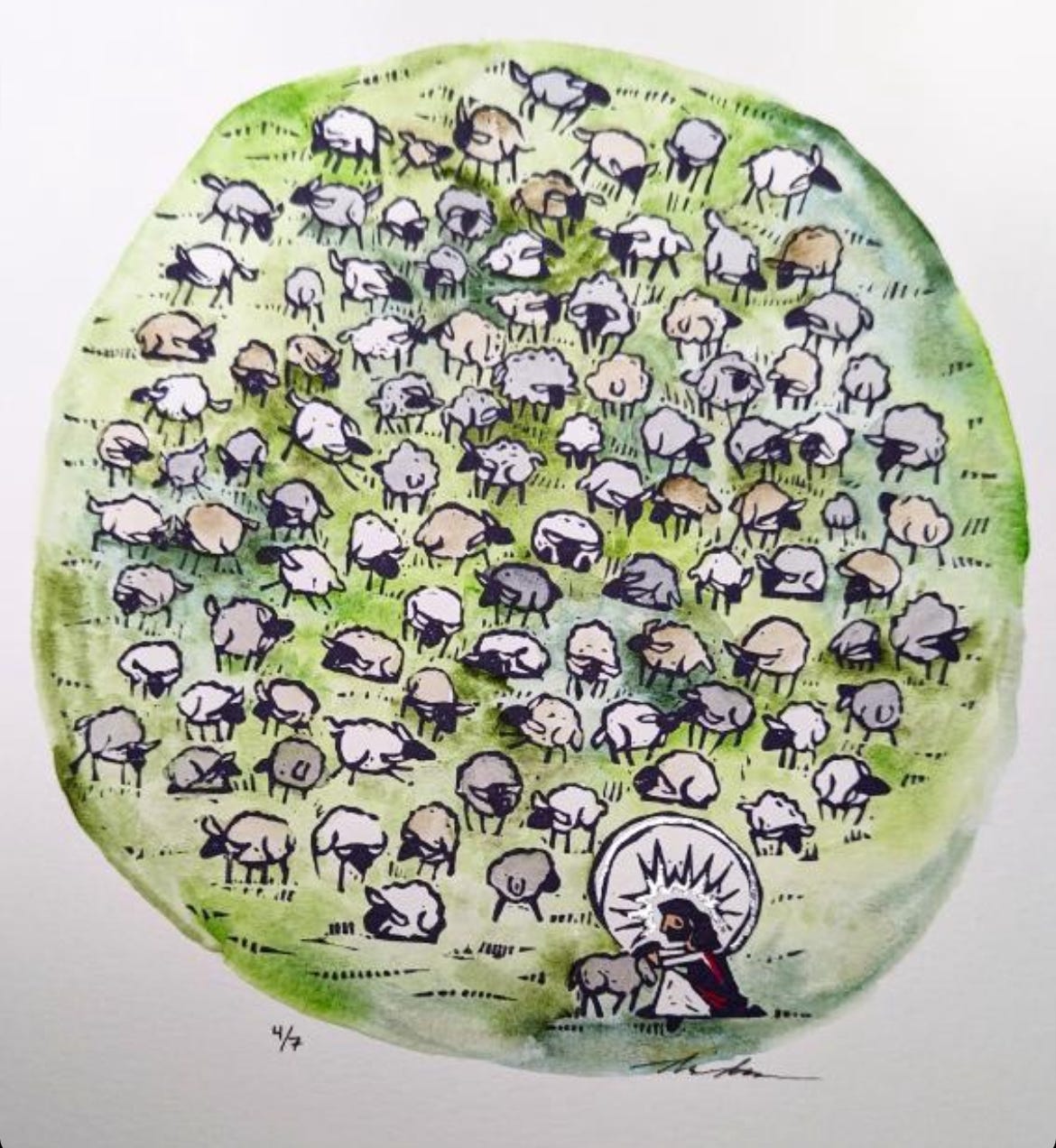

We are motivated to act and acquire things that will best satisfy our deep unmet needs. Manfred Max-Neef taught that human needs are few, finite, and classifiable but that it “is in the infinite ways that we satisfy those needs that the diversity, wastage, and muddle occurs.” President Spencer W. Kimball taught that Jesus saw sin as springing from unmet needs. However, people may also perform acts of saintly service to satisfy their deep unmet needs. And all of us likely do both—sin and serve. For example, the sons of Mosiah, responding to changes in the relative importance of their deep unmet needs left off being “the vilest of sinners” and became the greatest of missionaries who “were desirous that salvation should be declared to every creature” (Mosiah 28:3).

Since our needs don’t change, except in relative importance, what accounts for our choices to sin or serve? The answer is complex. However, one important influence is our relationships with others, ourselves, and God that range from antipathy to empathy. Our relationships can motivate defensive and destructive acts that produce negative consequences and also motivate acts of sacrifice, sharing, and service capable of producing “the happiest of people” (4 Nephi 1:16).

To begin this discussion, I describe five fundamental needs that we seek to satisfy, how our relationships influence how we seek to satisfy those needs, and emphasize the importance of avoiding hard feelings. While I do not claim that these five fundamental needs are comprehensive, I have found that they explain much of what I study in behavioral and socioeconomics, ponder in the scriptures, observe in current events and experience in my own personal life.

A brief description of these five fundamental needs follows.

1. Our need for internal validation.

We need internal validation or approval from our ideal self, often referred to as our conscience. Our ideal self is connected to our personal values which may be defined by our relationship with God and people we admire. Dale Wimbrow’s poem “The Man in the Mirror” describes our connection to our ideal self and our need for internal validation.

When you get all you want and you struggle for self, and the world makes you king for a day, then go to the mirror and look at yourself and see what that man has to say. [because] . . . the man, whose verdict counts most in your life is the one staring back from the glass.

2. Our need for external validation.

We need external validation or approval from the important people in our lives. This need may explain the popularity of books designed to help us do just that—win friends and their approval. Dale Carnegie’s book How to Win Friends & Influence People, for example, has sold over 30 million copies.

3. Our need for commodities.

We need commodities that satisfy our fundamental physical needs including food, shelter, safety, and clothing sometimes referred to collectively in the scriptures as bread (Matthew 4:4).

4. Our need to belong.

We need to feel that we belong and feeling left out can produce severe physical and emotional consequences. There are two ways we satisfy our need to belong: by fitting in or by finding our community.

Fitting in

To fit into a community, we adopt the values, customs, traditions, and objects of worship of the group we wish to join. To fit in, the children of Israel abandoned the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and worshiped other gods including Baal, Ashtaroth (Judges 2:12-13), the gods worshiped in Syria, Sidon and Moab, and the gods of the Ammonites and Philistines (Judges 10:6).

Belonging

Paul taught us not to “conform to the world” (Romans 12:2). Instead, we need to find a community where our ideal self feels at home, where we feel accepted for who we are. In the early church, some Jewish sects insisted that Gentile converts fit in by following the Mosaic law that required them to be circumcised. In contrast, Paul taught that belonging to Christ’s church, converts needed an inward circumcision of the heart, something they had already experienced (Romans 2:27-29).

5. Our need for transcendence.

We need to respond to the conditions of others. A poem by John Donne reflects this need to make the conditions of others our own.

No man is an island entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less . . . any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind. And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

President Gordon B. Hinckley taught that new converts need three things: a friend, a responsibility, and nurturing with ‘the good word of God.’” However, not just new converts but all of us need a friend who can provide external validation and a sense of belonging; a responsibility that can provide opportunities to earn internal validation and transcend our narrow view of who matters; and to be nurtured by the good word of God to educate our conscience.

The relative importance of needs

The relative importance of our needs depend on which needs are most pressing. For example, it’s hard to focus on the word of God when we’re hungry. When David O. McKay was a young missionary in Stirling Scotland, he knocked on the door of a poorly dressed woman with sunken cheeks and unkempt hair. He offered her a gospel pamphlet which she accepted and then asked: “Will this buy me any bread?”

Relationships have an important influence on whether we sin or serve when attempting to meet our deep unmet needs. For that reason, we should avoid antipathy and hard feelings. We learn this important lesson from Moroni’s soldiers. After difficult times, they alternatively choose to have hard or soft feelings. “But behold, because of the exceedingly great length of the war between the Nephites and the Lamanites many had become hardened, because of the exceedingly great length of the war; and many were softened because of their afflictions, insomuch that they did humble themselves before God, even in the depth of humility” (Alma 62:41).

It is the nature of our mortal experience to be bumped and bruised by those around us, even by those whom we thought were unlikely to do so. And even when no offense was intended, we likely suffer from the “actor-observer” bias, the tendency to attribute our actions to external influences and the actions of other people to internal causes. For example, when others are late, it’s because they failed to prepare and plan. When we are late, it’s because of heavy traffic. Therefore, we will all be presented with opportunities to develop feelings of apathy, antipathy, fear, and disdain for another person or group. And from there it is a short step to enlist others to validate our feelings by creating relationships based on shared antipathy. To avoid the bonds of such dysfunctional connections we should refuse to be offended. One verse of a favorite hymn teaches:

Should affliction’s acrid vial Burst o’er thy unsheltered head, School thy feelings to the trial; Half its bitterness hath fled. Art thou falsely, basely, slandered? Does the world begin to frown? Gauge thy wrath by wisdom’s standard; Keep thy rising anger down.

I learned this lesson powerfully in my youth. I grew up in a town small enough that everyone was each other’s neighbor. Thus, any conflict between neighbors became a community cause. It was in this setting that a tragedy occurred. At the end of their school year, several young men from my town went together to a distant town for summer work. Most of the young men were experienced wild game hunters and had brought firearms with them. One evening together in their apartment, one of the young men, unfamiliar with the operation of firearms and curious, accidentally fired a loaded pistol and killed one of his friends.

Our community was paralyzed. We were all connected to the young man who accidentally fired the pistol, and the slain young man, and their families. My dad, who was close to both families, told me what happened next. Amid their sorrow, the parents of the slain young man (call them Jim and June) went to the young man who accidentally fired the pistol and his parents and said (paraphrased), “What happened was a horrible accident. But we want you to know that our family holds no hard feelings. We know that something like this can ruin a person’s life and we don’t want that to happen to you.” Jim and June’s noble act saved our community and made it possible for my town to go about the process of healing. It also taught me to avoid hard feelings (Psalms 95:7,8).

Our deep unmet needs motivate us to act. We satisfy our physical needs by employing various forms of capital to produce and exchange commodities. We satisfy our needs for internal and external validation, belonging, and transcendence by connecting with others on our island and by employing our relationships to produce and exchange relational goods. The nature of our relational goods and commodity exchanges depend importantly on the nature of our relationships whether they be empathetic, antipathetic, or something in between. Sin often involves seeking to satisfy one’s deep unmet needs with antipathetic feelings. Our best approach is to embrace empathy, rather than antipathy, at every opportunity. A noble couple in my hometown taught me this lesson many years ago.

Lindon Robison is an Emeritus Professor at Michigan State University. From 2004-2007 he was President of the Spain, Malaga mission, for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Artwork by Alice Abrams.