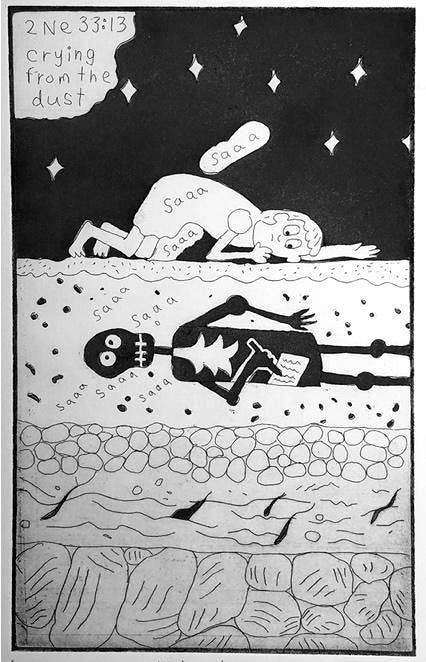

At first glance, the image looks like a spooky Halloween scene. Under a star-filled night sky, a girl hears whispers rising from underground. She kneels, pressing her ear to the earth to listen more clearly. Obscured from her view, a wide-eyed skeleton lies directly below her. He writes with a stylus on a sheet or plate. His whispers of “saaa” float from his bony mouth, through the layers of earth above, over the girl, and into the heavens. The artist’s use of a black-and-white printing technique and a cartoon-like style enhance the playfully macabre mood. A white cloud in the upper left corner contains the words, “2 Ne 33:13 crying from the dust,” indicating that the skeletal figure is the ancient American prophet Nephi.

In this deceptively simple image, I see Latter-day Saint theology in action. Theology is motivated by a desire to better know God. It is best accomplished when faithfully based on a process of scripture study and revelation. Thus, theology requires trust, effort, and an openness to new ideas. Done properly, theology changes our perspective and creates the possibility of transformation. In his formulation of “Mormon theology,” philosopher Adam Miller described its four essential components: 1) charity, or a concern for the problem of human suffering, 2) careful and sustained attention to scriptural text, 3) speculative and hypothetical analyses, and 4) a collaborative approach. In each of these four ways, Annie Poon’s Whispers demonstrates how visual art can not only illustrate religious ideas but also participate in the work of Latter-day Saint theology.

First, Poon’s print exhibits charity in its treatment of the human condition. A series of visual opposites create feelings of tension and urgency. Most noticeably, the image is divided horizontally between the black sky of the living world and the white dirt of the earth below. The two figures mirror each other, with the white circle of the girl’s shoulder and the black circle of the skeleton’s elbow lining up in the center of the image. The startling reflection of a physical, active body with a buried skeleton evokes the universal human experience of pain and death; the dead were once alive, and the living will die. The image blurs the edge of where life ends and death begins, as Nephi appears long dead yet still writing and whispering. Further friction is introduced by the inability of the two figures to see each other despite their proximity. Additionally, the past and present collide as the ancient prophet’s words reach the ears of a modern girl. These numerous oppositions—black and white, heaven and earth, flesh and bone, dead and alive, seen and unseen, past and present—visually reflect the unease of the human condition and an earnestness in seeking resolution.

Second, Poon’s artwork calls attention to the scriptural text. It does so overtly with the short reference written in the cloud. It also does so implicitly through visual symbols, including the scribbled lines on the plate and the floating whispers. The final chapter of Nephi’s message, in 2 Nephi 33 of the Book of Mormon, comprise merely fifteen verses. In that short space, Nephi used a form of “write,” “speak,” “cry,” or “words” an incredible twenty-eight times. In these final lines of his record, he pleads with both his brethren and the “ends of the earth” to believe his words and to believe in Christ. Accordingly, in the artwork, Poon makes the word—and the hearing of the word—paramount.

Third, Poon’s artwork is creative and exploratory. It takes advantage of the printing medium to depict a scene that could only be imagined. By encouraging the viewer to see differently, the artist helps the viewer to think otherwise. The image seems to ask, what happens if we accept the collapse of time and space as immediately present rather than as an abstract concept or a future event? Poon visualizes this hypothetical by showing layers of geological time in a cross-section of earth and the material connection between the listening girl and the speaking skeleton. What might this understanding of existence mean for me today? What does it tell me about the nature of God?

Finally, Poon’s print models the collaborative work of theology. As the girl needs a prophetic messenger to bring her the word, so Nephi needs a listening ear to fulfill his mission. Together, they are anxiously engaged. As a work of art, the piece also creates a relationship between the artist and the viewer. The artist visualizes her ideas and testimony, appealing to the heart and mind of the viewer. The viewer, in turn, brings his own perspective and experience, influencing how he understands the artwork. As with the reading of scripture, it is the process of engagement that brings the art to life and sparks revelation.

Indeed, engaging with this artwork spurred my own theological reflections. In considering Nephi crying from the dust, I thought about the last Book of Mormon prophet, Moroni, who, more than 900 years after Nephi, concluded his record with similar references to the dead speaking. In Mormon 8:23 he wrote, “Search the prophecies of Isaiah. Behold, I cannot write them. Yea, behold I say unto you, that those saints who have gone before me, who have possessed this land, shall cry, yea, even from the dust will they cry unto the Lord; and as the Lord liveth he will remember the covenant which he hath made with them.” Like Nephi, Moroni’s final message emphasizes speaking, crying, writing, and words. Both prophets indicate that the purpose of it all is to bring people to a remembrance of the covenant. Where Moroni points to Isaiah’s explanation of covenant, Nephi more directly explains that if the word is believed by his people then “it persuadeth them to do good; it maketh known unto them of their fathers; and it speaketh of Jesus, and persuadeth them to believe in him, and to endure to the end, which is life eternal” (2 Nephi 33:4). Again, in Mormon 9:30 Moroni declared, “Behold, I speak unto you as though I spake from the dead; for I know that ye shall have my words.” While Nephi repeatedly speaks to his people (including Moroni), Moroni writes to me. Reading the words of these prophets together helps me better understand my place within the covenant prepared by a loving Heavenly Father.

Also, as I spent time with the print, its visuals unexpectedly brought Alma 32 to mind. In the artwork, the word (Nephi’s written message) is literally buried underground, like a seed. The girl walking above hears a faint whisper. A divine message slips into the world. Paying attention, the girl arouses her senses, gives place for the word, and actively bends down to better listen (see Alma 32:27). The whispers pass over and through her. One “saaa” is written across her body, perhaps symbolizing her effort to internalize and experiment upon the word. As she does, will the word, like a seed, spring up from underground? Will she tend to it so that it becomes a tree of life for her? Will she taste its sweet fruit? Will she allow for the possibility of her transformation? Will I? The mirrored pose of the skeleton and the girl takes on additional meaning as I consider a mirrored image of the tree of knowledge, which introduced death into the world, and the tree of life, which introduces the possibility of mercy and eternal life (see Alma 32:41-42). Life comes only through the word, which, in this artwork, is brought to us from the dead. Poon’s image inspired me to read Alma 32 in the context of Nephi’s prophetic message and the role of the Book of Mormon itself. Doing so helps me reflect on the interrelatedness of my mortality and Christ’s atonement.

Whispers provocatively captures foundational elements of Latter-day Saint belief. More, though, it demonstrates the power of art as a theological tool. It engages with scripture in novel and faithful ways to open new avenues of understanding. It shows how we might read scripture as not just an analogy for our lives but as, startlingly, about our lives. It visualizes the haunting cry from the dust of the prophets and our urgent need to listen carefully. It directs us to the word. It points us to Christ.

Jennifer Champoux is an art historian and the Director of the Book of Mormon Art Catalog.