Confusing Grace

The doctrine of grace has always baffled me. It’s a doctrine that’s everywhere in Christianity, and many Christians say that it is only Christ’s grace that saves us from sin and hell. The crux of the Christian message is that the love and grace of the Creator of all things is freely and fully given, with no necessary performance on our part.

As someone who suffers a great deal from bipolar disorder and OCD, grace is a doctrine that has kept me up at night. It has caused me great emotional and mental despair. How can grace exist when I have often felt so broken and abandoned? Angry and afraid?

In April 2024, I had a manic episode that lasted thirty days, a period of unusually high energy, mood, and impulsive behavior that made me feel out of control. Before my episode, my mental illness manifested primarily as major depression, accompanied by suicidality and self-harm. I spent a week in the mental hospital during the summer of 2023. And even through those dark, depressive days, I believed that God was there and had his eye on me.

But mania was different.

The terrific yet disheartening thing about my manic episode was that I felt great. I felt a confidence I had never felt in my life, or since, but it came at the cost of an unhealthy and potentially dangerous cocktail of chemicals in my mind. I acted strangely. My heart hardened, and I couldn’t feel affection for my family or anyone else. I felt nothing inside, except for energy and confidence that bordered on delusion. Others at church asked my wife if I was okay, mentioning that I seemed “off.” When I learned about that some time later, it embarrassed me, and I felt great shame.

During this time, I felt “allergic” to church and religious things in general. I wish I had words to explain how I felt when I listened to conference talks or sat in the pews at church. It felt like a swarm of bees trying to get in my ear. It was as if the Church and the gospel were water and I was oil—something in me couldn’t mix with what was taught.

I took my medicine as prescribed every day, and I did everything I was supposed to do to the best of my ability, yet the mania persisted. I felt cheated.

Then came the inevitable crash.

As I’ve learned since, extended manic episodes fry the brain, completely changing how it processes dopamine and serotonin. When that happens, what makes someone feel happy or rewarded is substantially altered, and it requires great healing to return the brain to its former baseline.

After the episode, no matter what I did, I couldn’t find peace or happiness. I felt as the psalmist: “In the day of my trouble I sought the Lord: my sore ran in the night, and ceased not: my soul refused to be comforted” (Psalm 77:2, KJV). My entire perception of reality flipped, and all my spiritual experiences up to that point in my life began to disappear from my mind like the last feeble embers of a dying fire. My grasp on the reality of those experiences barely hung on, and I thought I had deluded myself. That I had been deceived.

Doctors, therapists, and Church leaders told me that the episode wasn’t my fault, but I felt God’s disapproval everywhere I went. Scarcely ten minutes would go by, and the thought that I angered God would rampage through my mind. I chased that thought over and over until I was run ragged. I couldn’t recognize who I was spiritually.

Grace was my fixation. I spent hours furiously thinking about it, trying to wrestle with it, hoping to pin its meaning down to see if I had sinned so grievously that I was disqualified from receiving divine aid. Even just receiving “the crumbs from the Master’s table” would have been enough (see Matthew 15:27). One day, I even debated with ChatGPT for over eight hours to figure it out.

Most of what ChatGPT said was that grace is the constant assurance of God’s love and presence. But that made me feel that everyone was entitled to grace except me. I didn’t feel that assurance of God’s love or even his presence.

If I couldn’t feel him there in my pain, he might as well not have been there at all. I couldn’t see the difference, and the mere thought that he was there did nothing to comfort me if his presence didn’t soothe my pain.

I was drowning, and in no way did I feel that God was near or loving. In fact, in many ways, I felt he was laughing at me. It was as if he became the God Who Mocks when I needed him to be the God Who Weeps. It got so bad that voices in my mind told me I didn’t deserve my children, and panic attacks became more frequent, almost causing me to get into a car accident.

By then, it had been a little over a year since my manic episode. Prayer, scripture study, and church attendance became a sweaty match between what the doctrine teaches and what I thought God felt about me. No matter what I did, I felt like I would disappoint God. Should I take the sacrament? Everything in me screamed not to, even though I couldn’t think of any logical reason to say no. If I chose to, I felt like Christ was going to smack the bread and water out of my hand.

I finally got in with a therapist and was diagnosed with scrupulosity, a form of OCD that obsesses over spiritual and moral certainty. It had always been bubbling under the surface since I was young, but after my episode, it broke free and wreaked havoc.

Putting a name to it didn’t help much at first. It made me feel twice as broken. Not only did I have bipolar disorder to handle, but I now had OCD. My therapist challenged me to consider the possibility that God might be communicating with me in unfamiliar ways as a means of helping me resist the compulsion to wrestle with doctrine to the point of great distress, thus teaching me to exist between the extremes of certainty and doubt.

To someone with OCD, existing between extremes was like being asked to check for carbon monoxide without a detector or a breathing apparatus. If there was no carbon monoxide, I’d live. If there was, I’d never know before it killed me. It felt like a life-or-death situation.

Another challenge he gave me was to focus on one element of my life and be grateful for something within that element. Gratitude had always been difficult because I didn’t see how it could answer my questions. It seemed to me like a way to sweep things under the rug.

But I started anyway, deciding to be grateful for things that make me laugh.

For example, one time at Walmart, I couldn’t remember what else I needed to get, and I didn’t want to look through my wife’s texts to find it. I saw a buff guy walk by and remembered, “That’s right, we need protein powder.”

On another occasion, I decided to go to Deseret Book to get The OCD Mormon by Kari Ferguson, along with The Crucible of Doubt by Terryl and Fiona Givens and Is God Disappointed in Me? by Kurt Francom. This was a big step for me because I had been extremely apprehensive about reading religious materials. I took my books to the counter, and after the clerk scanned them, he sighed and said, “Okay, I need to check in. Are you doing okay?”

His question floored me. I wasn’t okay, but I said, “Yes,” anyway. It was unexpected and funny. I’m deeply grateful for his perceptiveness and bravery in asking the question.

Counting the humorous things in my life helped me feel happier, but I still felt a great distance from God. I tried so hard to be comfortable with the possibility that I might never feel the Spirit again as I had before. But I did notice I stopped worrying so much about grace. It would come up occasionally, but I was getting better at managing it.

Then, several weeks later, as I was getting ready for work, my one-year-old son crawled to me and started clawing at my legs to stand up. A powerful feeling came over me, telling me that God sees me the way I saw my son in that moment—as his child just trying to stand up, clawing his way to his feet.

I couldn’t believe it. Aside from a few happy moments, this was the first time I had felt something other than sadness and anger in over a year. I squeezed my son tightly before putting him down to leave.

Driving to work, I listened to my Sunday playlist instead of my normal, loud rock ’n’ roll. As the music played, I felt a bit more at peace.

I couldn’t help but be apprehensive. Was this really happening?

Then, when on a break at work, I thought I’d read the lyrics to some Mumford & Sons songs from my Sunday playlist that had helped me feel the Spirit before. One of those songs was “Ghosts That We Knew.”

I had heard this song a billion times, but when I read it in my office, the first verse broke me open:

You saw my pain washed out in the rain And broken glass saw the blood run from my veins But you saw no fault, no cracks in my heart And you knelt beside my hope, torn apart

Love and light flooded my soul, and tears blurred my vision as I wept. At this simple moment, as I read the lyrics to a familiar song I love, an unexpected, undeserved feeling of love came over me. The anger and resentment I had carried from the past year melted away in seconds.

I felt Christ saying to me, “I saw your pain. I saw the times you’ve made yourself bleed. I saw and heard you cry out many times for me to take it from you. I knelt beside you through it all, and I see no fault or brokenness in your heart, and you are whole before me.”

Though I was not guilty of the same sin, I felt as I imagine the woman caught in adultery must have felt when Christ said, “I do not condemn you” (see John 8:11, NKJV).

The OCD part of me immediately tried to destroy that beautiful moment, to find a reason why this happened, and when exactly I earned it. The therapy helped me to stop that compulsion.

I cannot deny that I encountered grace. Nothing other than the power of God could have made that anger and resentment fade away, replacing it with a feeling of wholeness I never thought I’d ever experience again.

I still can’t fully explain what grace is. But I believe it’s real.

I had thought that God wasn’t there, or that if he were, I would have felt relief, especially when I needed it most. Instead, Christ’s grace reached me when I didn’t demand it or expect it. Thinking back on when I was at my lowest, I probably would have rejected grace then and wouldn’t have recognized it for what it was. It came at the right time, which means that God had to have been watching me so closely as to know when the right time would be.

This isn’t to say that I’m cured. Far from it. Since that day at work, I’ve had several depressive and discouraging episodes and OCD flare-ups. But I’m learning to better manage it and come to terms with the fact that I’ll always have to monitor my mental health.

But I trust that Jesus is good and patient, acutely aware of the ins and outs of my mental health, and knows what’s best for me.

I know this isn’t the most helpful story for people who are where I was. It’s much easier to tell stories of hope when we’re safely on shore. For those still treading water, I know what it’s like to lose hope. I won’t tell you to keep going because you’ve heard it a billion times. But if you are lacking faith, feel free to rely on mine because I am a witness that Christ’s grace guides and lifts us.

I expected to feel grace at my lowest, but I didn’t.

But grace did come.

Confusing, surprising, amazing grace.

Doug is married to Tanne Murdock, has two sons, and works as an attorney. He writes about the intersections of faith and mental health, drawing on his own experiences living with mental illness.

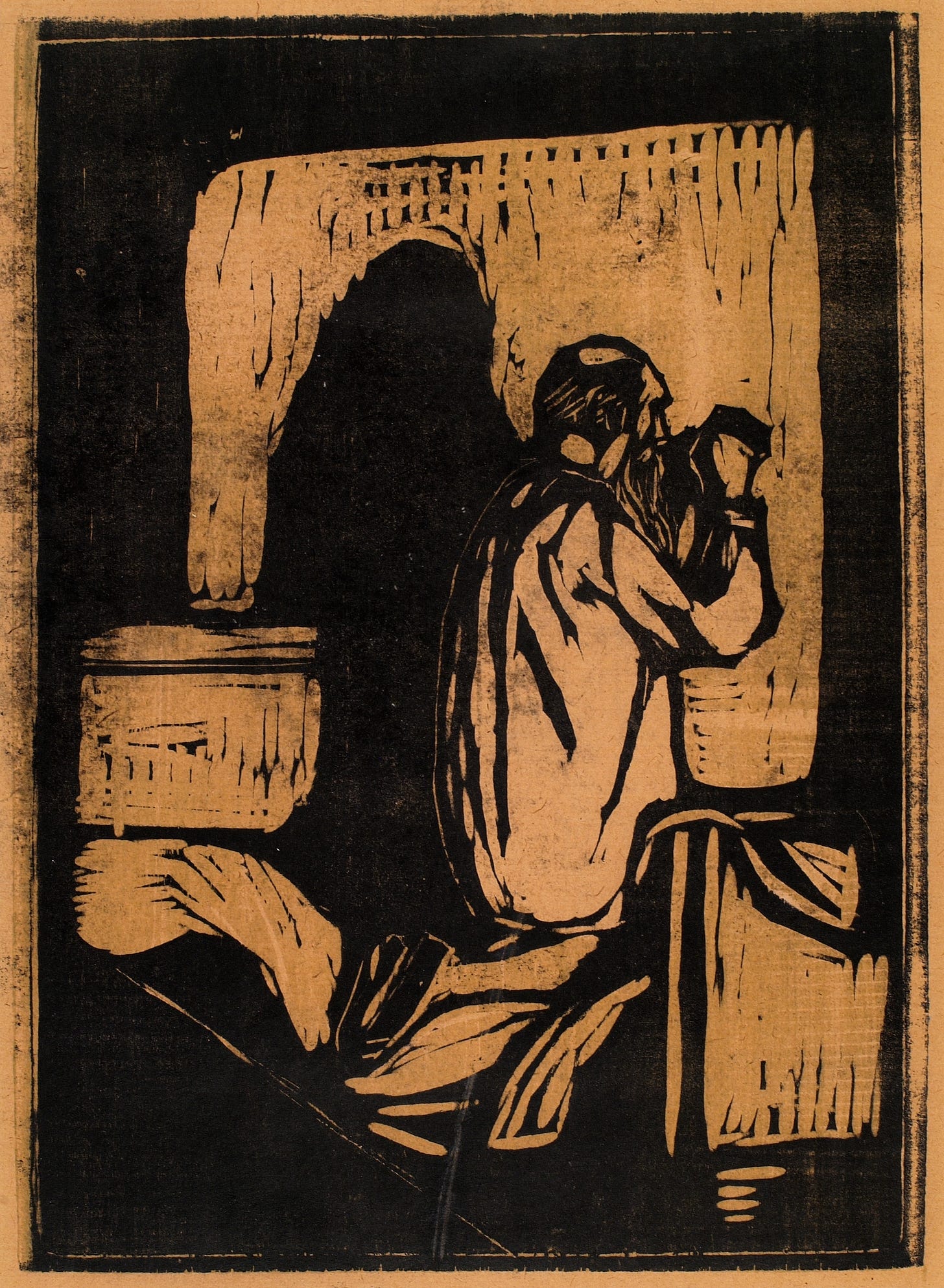

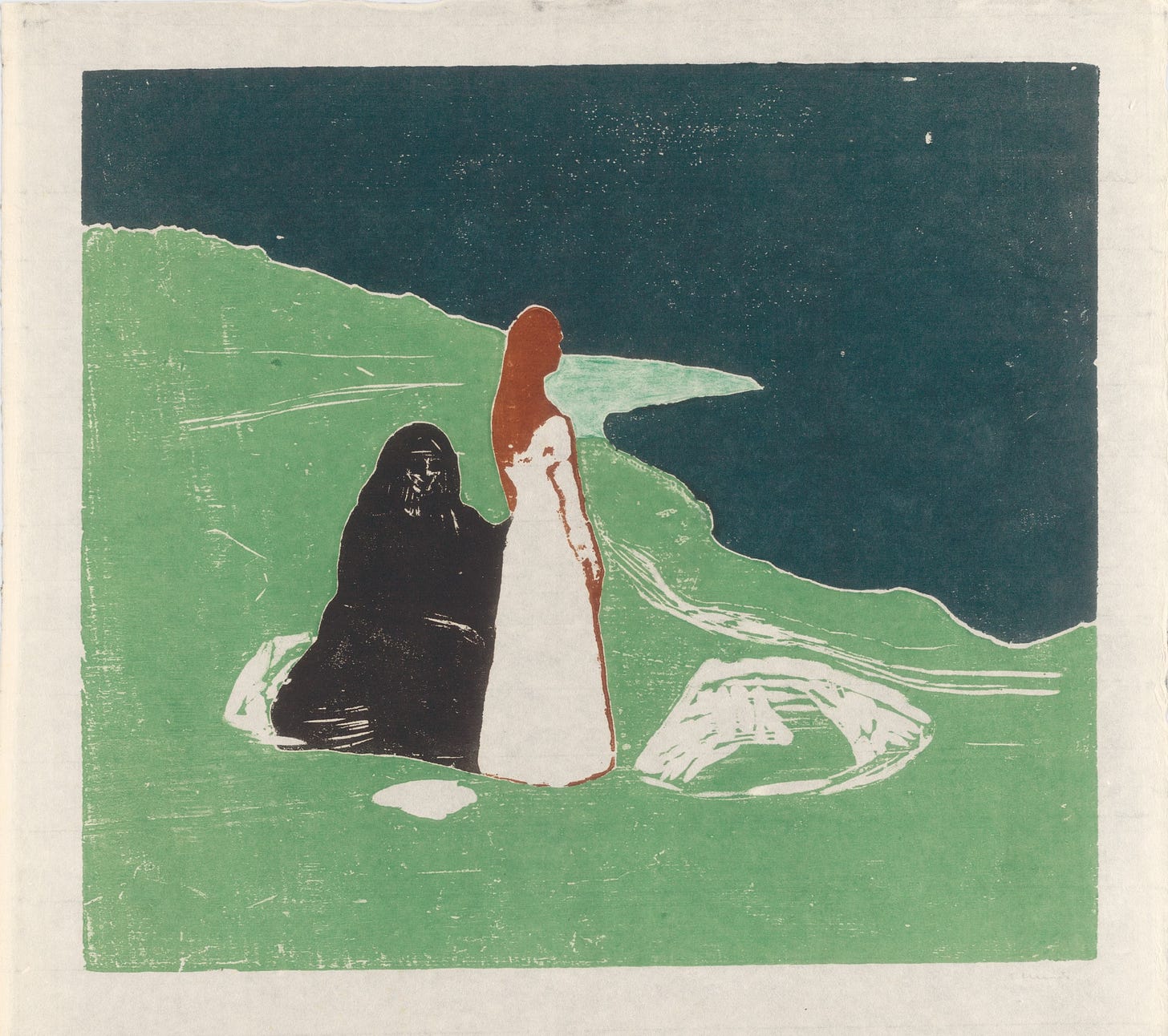

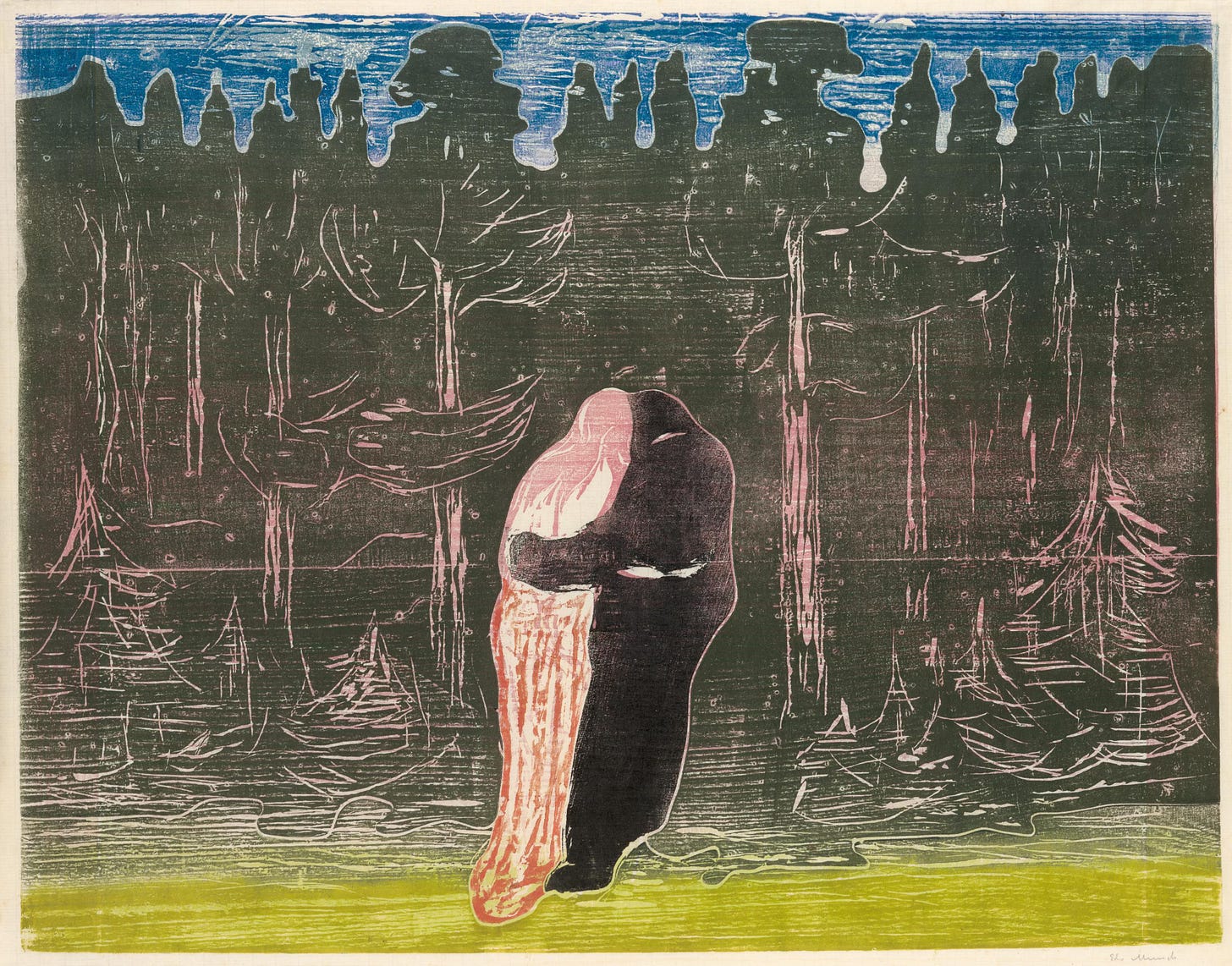

Art by Edvard Munch (1863-1944).