Come, Lord Jesus

An Advent Invitation

At my children’s episcopal play group, Mother Nora carefully arranges four dark blue blocks next to two white ones in the circle of the church year, each block representing one week. “Advent,” she explains, “is the time for getting ready for the Mystery of Christmas.” Just as Lent offers six weeks to get ready for the Mystery of Easter, Advent is the season of the Western Christian liturgical calendar that immediately precedes Christmas and offers the opportunity to intentionally prepare for something important, something mysterious. In a world of instant gratification and same-day delivery, Advent invites us to hold off, to wait, to allow a bittersweet longing to build up, and presents the possibility that our Christmas celebrations will be all the more meaningful for it.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a German Lutheran pastor and theologian, wrote extensively on Advent and Christmas while imprisoned during World War II for anti-Nazi resistance. From his prison cell he wrote, “Celebrating Advent means being able to wait. Waiting is an art that our impatient age has forgotten. … Whoever does not know the austere blessedness of waiting—that is, of hopefully doing without—will never experience the full blessing of fulfillment. … For the greatest, most profound, tenderest things in the world, we must wait. It happens not here in a storm but according to the divine laws of sprouting, growing, and becoming.”

Exactly what this season of preparation and waiting looks like can and should vary from person to person and from year to year. Ten years ago, Dr. Eric Huntsman’s introduction to a Latter-day Saint Advent inspired me to integrate an Advent practice into my spiritual life. In the years since, my Advent observance has taken many forms and has become an increasingly meaningful spiritual practice. It has molded and changed me, even as it has adapted to meet my ever-changing needs.

The gift Advent offers me in this season of my life is the space to acknowledge that all is not yet as it should be. In years past, moving abruptly from distressing news reports and personal challenges into Christmas celebrations has been jarring. Once-beloved traditions seemed trivial in the wake of a life-altering medical diagnosis for my spouse. Buying my children presents was painfully unsettling as I thought of other children suffering the effects of poverty and war. Familiar carols have rung hollow during prolonged periods of spiritual uncertainty and silence.

Advent doesn’t ask me to pretend that all is well when I know with perfect clarity that it is not. Advent invites me instead to lean into my longing for a better world, and to allow that longing to move me towards hope.

Anglican priest Tish Harrison Warren writes, “For Christians, Christmas is a celebration of Jesus’ birth—that light has come into darkness and, as the Gospel of John says, ‘the darkness could not overcome it.’ But Advent bids us first to pause and to look, with complete honesty, at that darkness. To practice Advent is to lean into an almost cosmic ache: our deep, wordless desire for things to be made right and the incompleteness we find in the meantime. … We need collective space, as a society, to grieve—to look long and hard at what is cracked and fractured in our world and in our lives. Only then can celebration become deep, rich and resonant, not as a saccharine act of delusion but as a defiant act of hope.”

Paul may have referred to this same “cosmic ache” when he wrote to the Romans that “the whole creation has been groaning together as it suffers together the pains of labor.” God knows the miracle of new life—just like Mary’s Child and my own beautiful, perfect children—comes only after we lean into and obey the painful process of labor. And so I find it incredibly meaningful that Advent invites me to feel this deep, sacred, often painful longing, and teaches me to use it in creative, generative ways as I collaborate with God in bringing Christ—and all of the hope, peace, joy, and love such a Being represents—into the world all over again.

Advent allows me to name the reality of difficulties in my personal life, of despair and harm throughout the world—and then invites me to stubbornly insist that this is not the whole story. It has become for me an opportunity to recommit myself to choosing hope, building peace, finding joy, and cultivating love. Perhaps this is one reason why each Sunday during Advent, in the darkest part of the year, people gather to light Advent candles. Each week a new candle is thoughtfully added, until by Christmas Eve the wreath is a circle of light, pushing back against the darkness and insisting that yes, darkness is real—but so is light.

Advent reminds us that Christmas is coming, but is not yet. Christ is coming, but is not here yet. Peace is coming, Zion is coming… but it is not here yet. It teaches me that I don’t celebrate the birth of a Savior by closing myself off to difficult realities and uncomfortable emotions; I celebrate by allowing myself to feel it all and letting that depth of feeling inspire me to bring just a little more hope, peace, joy, and love into the world. It invites me to join in the work of “hasten[ing] the time” of peace on earth, goodwill to men. It reminds me that this is precisely the world to which “the dear Christ enters in”—and that, miraculously, I can be a part of that entering.

Each Tuesday before Christmas Wayfare will share options to explore for your own Advent observance. Through music, essays, stories of our own saints from Church history, poetry, artwork, recipes and more, we hope you will be inspired to join with us, in your own way, to bring more hope, peace, joy and love to the world this season, each of us lighting our own small candles against the darkness.

Cecelia Proffit and her spouse Conor Hilton are the authors of An Advent Reflection and Another Advent Reflection, two zines available from The ARCH-HIVE. She lives in Iowa with her family.

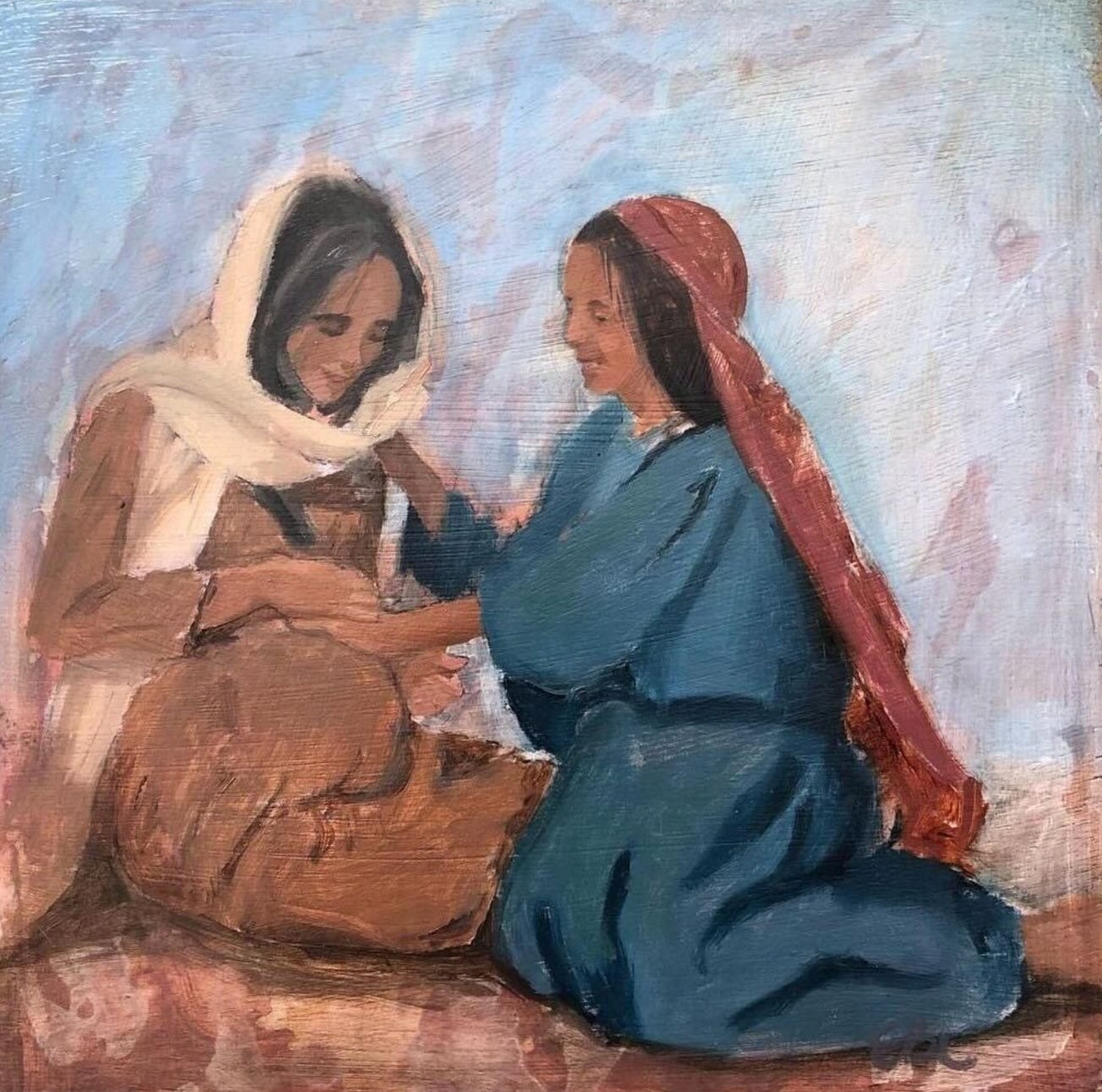

Art by Emilie Buck Lewis.

READ ERIC HUNTSMAN’S INTRODUCTION TO ADVENT

Good Tidings of Great Joy

When I was very young and living in East Germany, Christmas in our family began four weeks before Christmas Eve with the beginning of Advent. We made a fresh cut wreath from a fir or a spruce and put four candles on top of it and placed it on our kitchen table. On the fourth Sunday before Christmas, we lit the....