Circles, Suffering, and Stories

People wanted the world to be a story, because stories had to sound right and they had to make sense. People wanted the world to make sense. -Terry Pratchett

Two years ago, I went blind in my right eye. It started with a flicker in my periphery and then my vision became warped and I developed a chronic headache. I was in the last trimester of my pregnancy with my daughter. After she was born, I went to one ophthalmologist, then another. Finally, I sat across from a young retina specialist who scooted his wheeled stool close to face me and told me I had a uveal melanoma that was leaking fluid and causing my retina to detach. My first question was, “Will my vision ever go back to normal?” And he replied, “Maybe, but that’s not going to be the biggest priority now. We have to treat the tumor first.”

It took me a minute to register. Cancer. I had cancer.

Since then I have gone through radiation, three surgeries, countless appointments and medications, and at least forty-five mental breakdowns. I am still blind in my right eye. I am in remission, but this type of cancer is ugly. Based on genomic analysis of the tumor, it has a 73% chance of metastasizing to other parts of my body, usually the liver. Despite some new experimental immunotherapies and other promising treatments, metastatic uveal melanoma is considered universally fatal. I have an MRI every three months to check for metastases. For now, my scans have stayed clear.

“Why is this happening to me?” I have asked this question thousands of times for thousands of things, large and small. But getting my diagnosis plunged me into the deep end of existential searching. Trying to find an answer to this question is the process of meaning-making. In psychology, meaning-making is a way humans resolve the discrepancy and distress that an event may cause to their “global operating system” or worldview. It’s how we reconcile our experiences and maintain a sense of coherence: one might say meaning-making is one way of comforting ourselves.

Faith traditions provide structure and scaffolding for our individual mean-making, and I grew up in the Mormon tradition. I was taught that the things we experience in life are managed by a loving God who wants us to Learn Things. A lost promotion, a severed friendship, or a setback are God’s way of giving you an opportunity to become a better, smarter, and humbler person. Trials and challenges aren’t just an unfortunate reality, they are The Reason We Are Here.

It is useful to see setbacks as opportunities to gather one’s resources and try again; mistakes and heartbreaks can be wonderful teachers. But is there a point at which this framing is no longer helpful? For me, there definitely is. I lost my mother to breast cancer when I was 12 years old, and she was only 41. Now I am also a young mom with a cancer diagnosis. Did God intentionally do this to us? Theologians and philosophers have wrestled with the “Problem of Evil” for centuries and I have nothing new or noteworthy to add to that discourse. Suffice it to say, I no longer attribute my experiences to the willful machinations of God, nor do I view “Learning Something From This” as a moral imperative.

Author and podcaster Kate Bowler explores this theme in her writing. Like me, she was diagnosed with cancer, but hers was already metastatic and she wasn’t expected to survive. Before her diagnosis, she had conducted and published research into the American prosperity gospel and its central tenet that God rewards faith with wealth and health. Facing her own mortality showed her the ways in which she had unconsciously held onto this tantalizing idea. She decided to let go of control, and like me, she replaced “everything happens for a reason” with the simpler “everything happens.” She now focuses her work on deconstructing toxic positivity. (Years after her diagnosis, she has now been declared cancer-free.)

Though Mormonism may not partake fully of the prosperity gospel movement (see more here), it is easy to make the logical leap from believing that life is a test, to believing that God will reward you if you have enough faith, and in its corollary, if you don’t overcome an obstacle, you must not have had enough faith. But this logical leap is not inevitable. There are other ways of interpreting our hardships while embracing the central Mormon idea that our mortal lives are for us to gain necessary experiences. Scripture isn’t uniformly prescriptive, either. Some scriptures tell of miracles brought by faith and promise answers to prayers. Others suggest that some things are simply unknowable or unsolvable (“Canst thou by searching find out God? Canst thou find out the Almighty unto perfection?” Job 11:7). You can find stories that teach faith through pushing forward with determination, and some that teach faith through letting go. Ultimately, the meaning of someone’s experience is going to be individual (consider Melissa Wei-Tsing Inounye’s recent book, for another example), even within the same faith tradition.

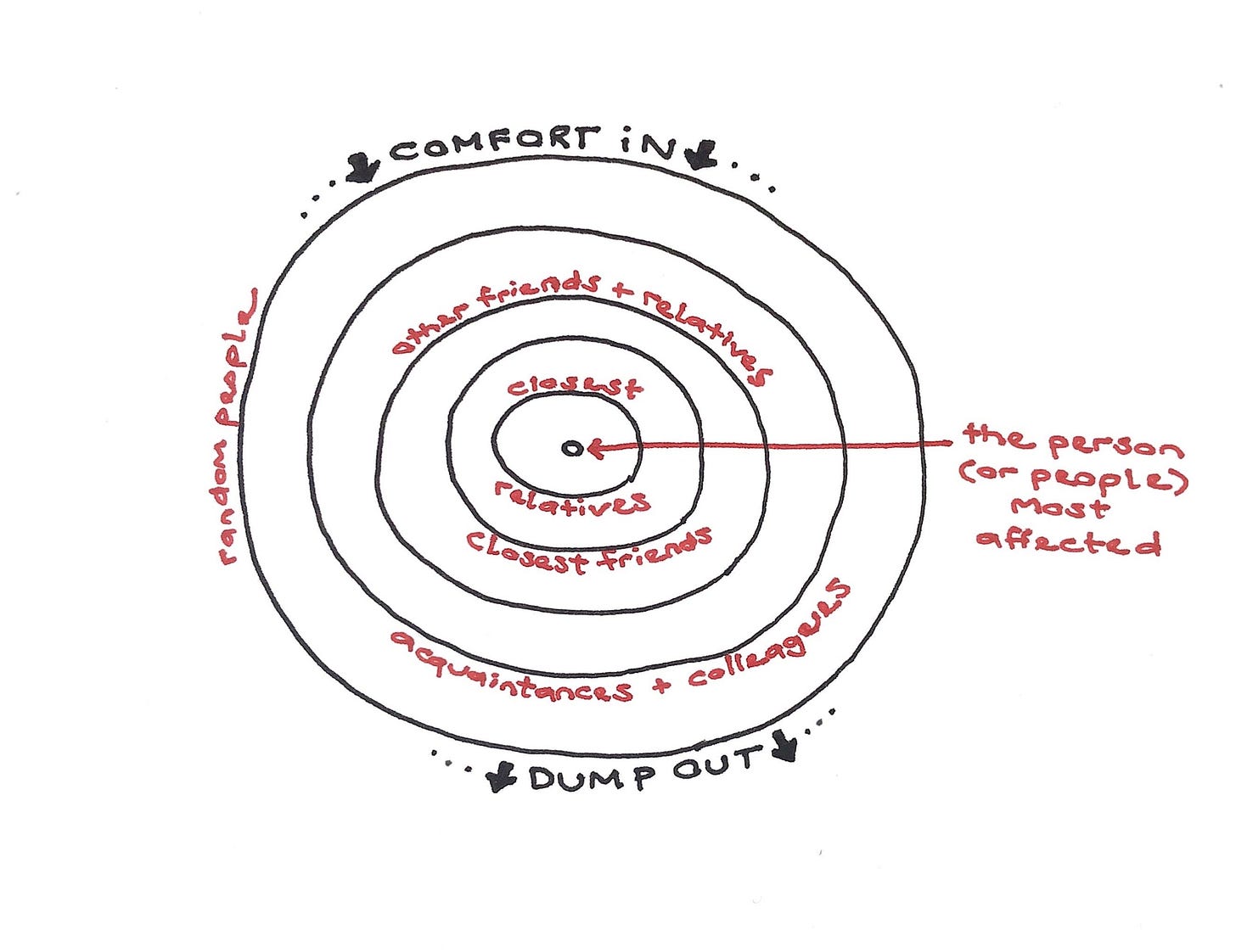

Ten years ago, Susan Silk developed the Ring Theory, which was a visual representation of the direction people should provide support during a crisis. Concentric rings surround a person in crisis, and each circle is made of people who are closer or further from the person in the middle. Significant others or close family, for example, often fall in the closest ring from the person in the middle. Next, close friends. Next, neighbors or acquaintances, and so on. The point of the visual is to help you figure out where to direct your emotional support (toward the middle), and where to direct your emotional dumping (toward the outside).

I had a conversation with a friend of mine about meaning-making. She observed that meaning-making has rings, too. Each of us stands at the center of our own meaning-making circle, and we get to decide what stories to tell about our lives. During the last couple of years, I have frequently found myself the object of other people’s storytelling about my life. Some of these comments were benign and easy to brush off, but others were genuinely hurtful. When someone outside the center ring tries to impose meaning on something we’re going through, they can get it wrong. Perhaps my neighbors’ meaning-making stories were meant less to comfort me and more to comfort themselves when my suffering violated their sense of rightness in the world. Adopting the Ring Theory could help with this. Silk’s “comfort in, dump out” mantra could be converted to “story-tell out, listen (and don’t assume) in.”

The last couple of years have been a crash course in meaning-making for me, and I’ve come to recognize that our faith community could learn to exercise more care in how we impose meaning onto the experiences of others. When providing comfort to someone in the middle of a crisis, it can be tempting to tell them why you think they’re going through what they’re going through (“God never gives you more than you can handle!”). But in making such statements, we may be unconsciously distracted by our own discomfort. We will go less astray when we reconsider our own motives for telling such stories to those at the center of suffering. It is risky to assume that someone else believes the same exact story, even within the same faith tradition.

Instead of offering explanations, let us instead offer our presence, our empathy, or our tangible help.

Katie Davis Henderson is a former water policy researcher, current full-time mom of two and writer about death, grief, cancer, gardening, and faith.

This essay was adapted from a post originally published at blue gray green lavender.

Artwork by Violet Frances.