Healing Powers: An Interview with Charlotte Condie

"I needed to learn how to sit in dissonance and disappointment."

Trina Caudle sat down with artist Charlotte Condie to discuss her journey in art and faith.

How did you get started in art?

Like a lot of artists, I was one of those creative kids who was always drawing. My father had graduated from Long Beach State in studio art, so he was my first contact point for creativity. It was my earliest language – I knew how to communicate and express myself that way. All through grade school and high school, I was in art programs. But it’s not what I got a university degree in. I got my bachelor’s in Asian Studies. I enjoyed studying languages – I took Japanese in high school, and during my senior year, I started Chinese at Utah Valley University. Chinese is a very visual language because many of the characters are conceptual; that was a great fit for my visual-learner brain.

I've always done art, but I haven't always sold art. I did collage a long time ago with magazines – I cut out pieces by color. I did a collage of the Newport Beach Temple – we moved to California before it opened. We volunteered at the open house, and that was where our two middle children were sealed to us. So that temple has a lot of family importance.

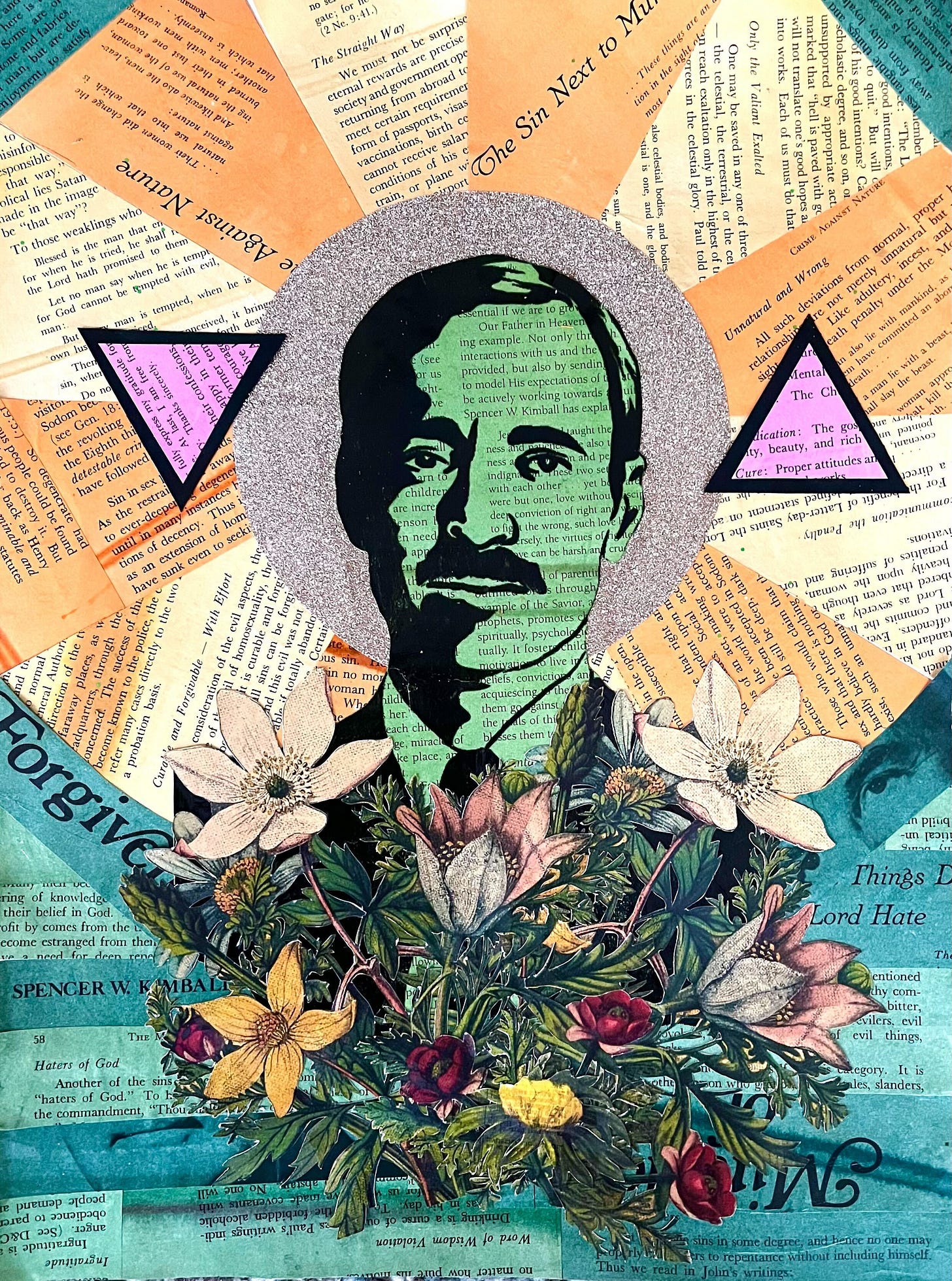

I really like vintage looks and old paper. I’ve worked with that for awhile, and also with digital illustration on an iPad – I’ve created originals and sold prints. Last year (2022), Latter-gay Stories put a call out for art made from Miracle of Forgiveness books. It was something I’d never done before – making art out of the pages of a book. I painted the book’s pages and put them on canvas. I thought at the time that the paint and canvas method didn’t work well, but I really enjoyed the medium of using book pages to create collage directly related to religious topics.

I had no idea what to do with this technique until Kurt Anderson and Camilla Stark and I curated a show at the Writ & Vision bookshop and art gallery in Provo, Utah in December 2022 titled, “I am Bound Upon a Wheel of Fire.” Kurt, Camilla and I all share scrupulosity, and it shows up in our different styles of art. Kurt does a lot of religiously themed illustrating penwork. Camilla’s work tends to be Gothic in nature and she focuses a lot on the Great Salt Lake. She also runs an art collective called the Arch-Hive, a group of artists that collaborate, cooperate, do shows together; the collective hosted the Scrupulosity show.

I immediately thought, “I have an old Mormon Doctrine book in my basement and I want to make art with it.” I started taking it apart and rather than painting the pages, I dyed them. I put water and dye in a tray, dipped the pages to soak the color into the paper, and then hung them to dry before using them. That was a new avenue for me – something not a lot of people do. I know a couple of artists who make collages out of vintage newspapers, really beautiful looking stuff.

I thought it might be interesting to use books that have cultural significance for us as Latter-day Saints. How can we move forward with this book? We can't ignore that it’s there, it existed and had an impact. So how are we able to create a new thing – whether it's a new version of our faith or a new way to church. We acknowledge the Church is always evolving and changing, so how can I take these old things that are painful and turn them into something better?

Can you explain scrupulosity?

It’s hard for people to understand obsessive-compulsive disorder because OCD has been so misused in our language. People don't use the term properly but treat it like a physical symptom of a quirk. But it’s extremely mental. For example, you spend a lot of time ruminating on something terrible that could happen, or working to get something just right, and these lead to the compulsion of reviewing something over and over and over. The compulsion is an action meant to alleviate the obsession but it just makes it worse.

Scrupulosity is a type of OCD that is preoccupied or obsessed specifically with the religious and the spiritual. People who tend to have scrupulosity often practice Orthodox Judaism, Catholicism, and Mormonism. (More about Latter-day Saint scrupulosity here.) You may already have some sort of obsessive disorder or an anxiety disorder, but then you add a high-demand religion, and you get a perfect formula for scrupulosity. People in any other religion may have experienced it, but few have the same level of life commitment that these religions do. It’s not just participation on a weekend, it's a lifestyle and a culture, it permeates all aspects of your existence.

My obsessions centered on perfection and moral exactness: I wasn’t good enough, I didn't repent often enough or well enough, I wasn’t worthy enough. I married young and my scrupulosity started soon after I was married. I was in several different young married wards, and I went to many bishops for the same repentance process over and over and over, trying to make myself feel better. There was no understanding that this is actually a unique form of OCD, so the bishops did whatever they could but it wasn’t helpful to me. It wasn't until I actually got medication that things quieted down and I didn't have those obsessions as much and I was able to control compulsive behaviors.

In addition to medication, how has your art helped ease the scrupulosity?

Working with the words on the pages of Miracle of Forgiveness was very cathartic. The words in the book felt very much like the words that pop up in my brain all the time. Everybody has thoughts in their brain all the time, but people with OCD latch onto them and can’t let go. It seems like a great idea to have a religion set up nicely that answers all the problems or questions you could ever think of. But for those of us with anxiety disorders and OCD, it just creates more problems with thoughts of perfection, or “I didn’t do that right,” or “I’m going to be judged for this,” or “I need to be punished for this and I’m going to hell.”

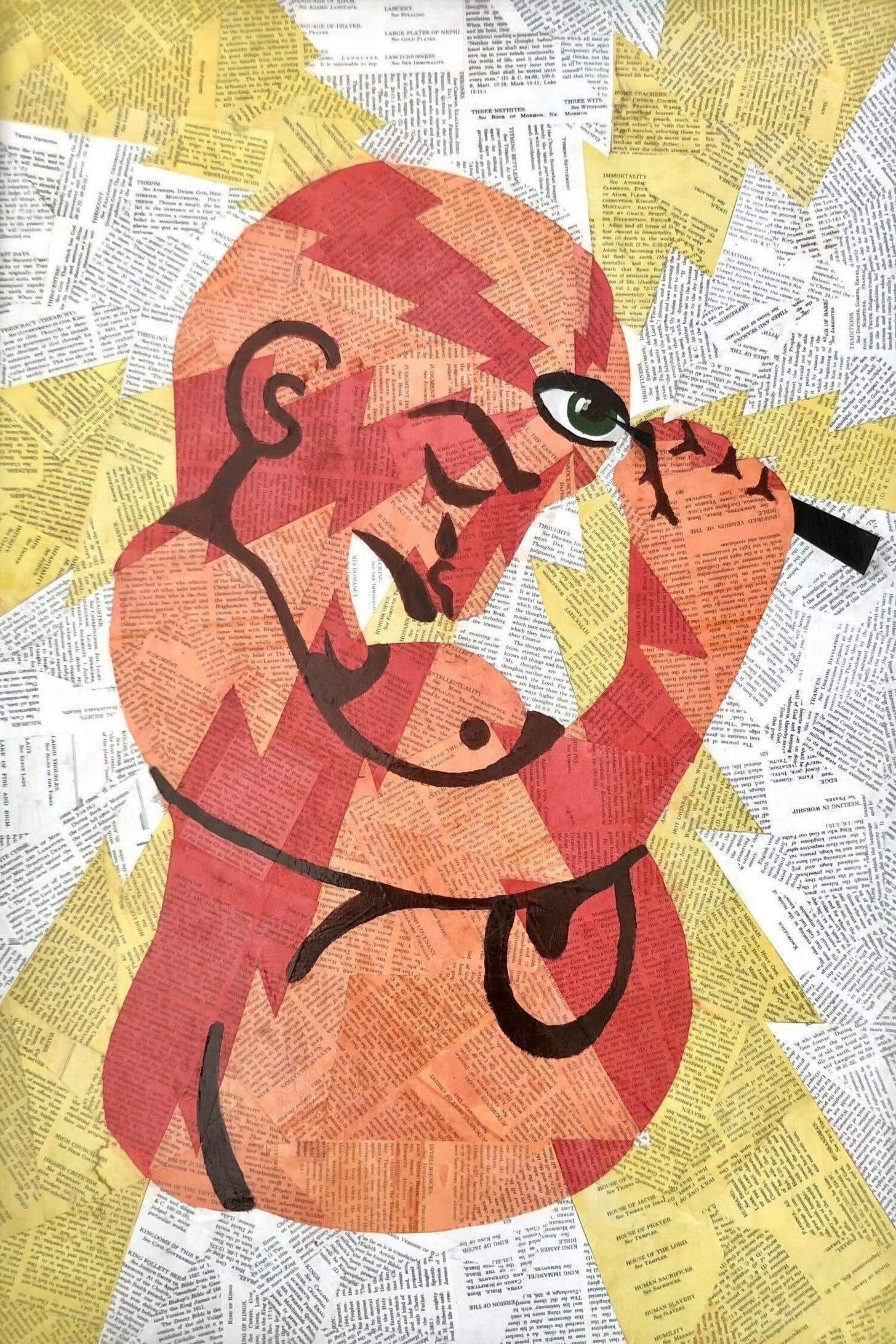

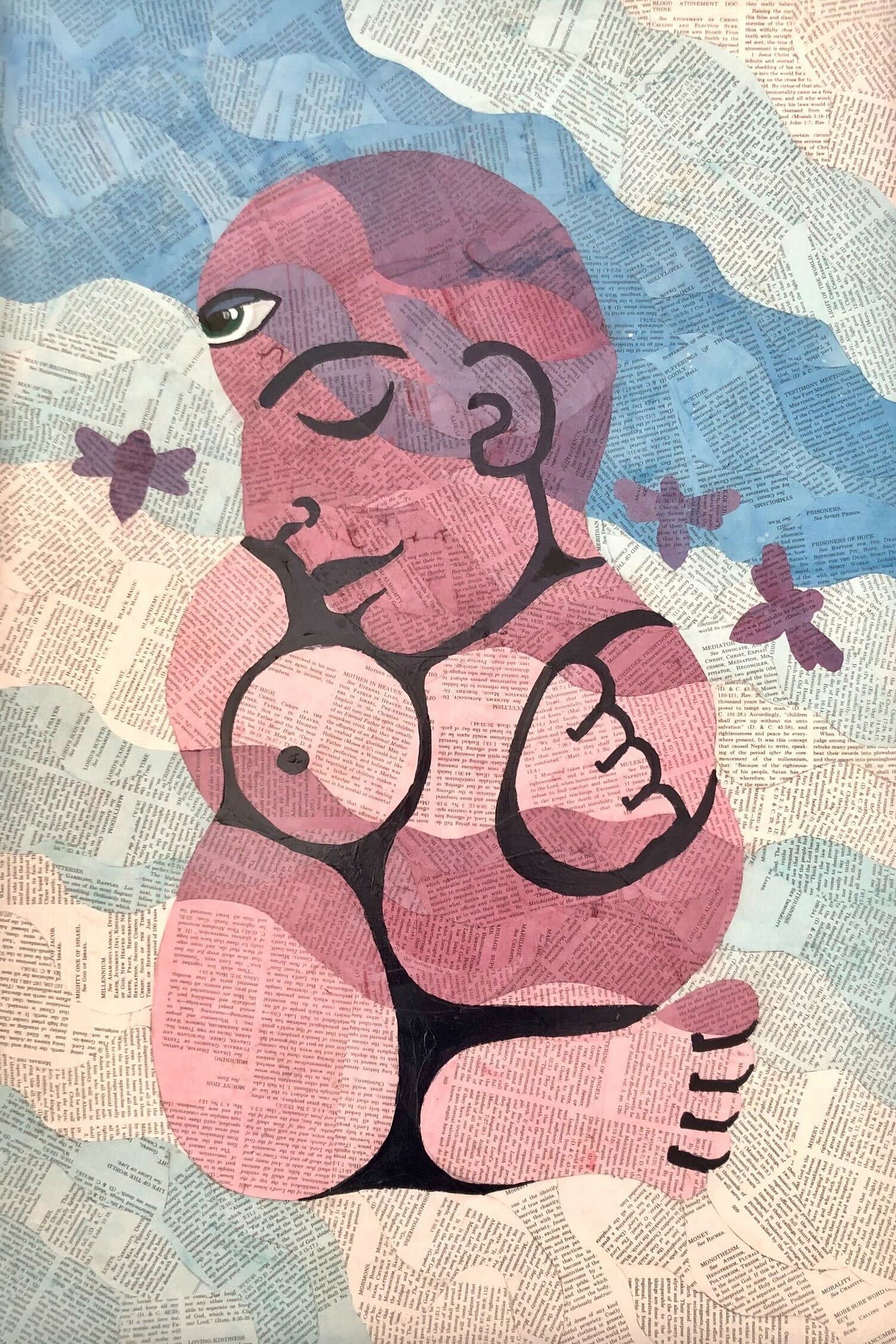

I tried to illustrate that with the art. The Mormon Doctrine book was the ingredient that did it best – the pieces of the book showing up in the images and the sculptures. And I love bold colors in my pieces, because I feel that is more emotive and stronger in language. The piece with the person poking out their third eye – there are jagged colors coming out of the mind of the person, to express the pain, and how much you want the pain to go away but you can't stop it. It’s complicated because this thing that you love so much and is part of you, and are obsessed with, is also causing so much pain. And the person eating the scriptures – if you look at it closely, there are rays or lines of color pointing toward the person and they’re ingesting what seems like a great idea but it can cause real harm.

What were you hoping that people would take away from the art show?

We had twenty-five artists who either have scrupulosity or a member of their family does; they all have a front row seat to that experience. We wanted those voices heard and to have people at least see what this is like for us, especially those of us who are trying so hard to participate in organized religion in spite of the real challenges it gives us. We can’t imagine ourselves as not part of the Church, or at least not having a close relationship with God or the spiritual. Religion is a great shoe box to put it all in, and we’ve got to put it somewhere.

Giving these artists the opportunity to say what they wanted to say and tell their story was really important. I think we did a really good job. We had great exposure, and it was a standing-room-only headliner for Writ & Vision. People were lined up out the door for over an hour on opening night. And then BYU acquired the entire show—that was real validation for all the work.

Somebody from BYU just showed up and said, “I want to buy the whole thing”? That’s awesome.

It was the Special Collections Library at the Harold B. Lee Library – they bought some of the physical pieces and digital images of the rest, everything from the entire show was acquired in some way. It was great because we all got paid – that was also really satisfying. It’s hard as an artist to feel successful, especially when it’s not the type of art that people will put in their living room – that stuff is hard to sell. But it's art that needs to be made because it says something.

What does this mean for BYU? Does it get held in an archive or displayed?

It will be in the archive. I have no idea how many shows they have in their collection, but I would love to see it displayed at some point in their gallery spaces. But it also means that the art department, or the psychology department, or any other academic community that intersects with this topic—they could use that information. The archive didn’t take just the gallery display. They acquired all of our sketches and process work, process videos, renderings of early concepts, and sketches. They have a big picture of what it looks like to put on a show, and all the mental process that goes into creating a piece, particularly one that involves a psychological disorder. So there are a lot of different ways they could use the show, and I hope they do. We were worried initially that it was going to be like the ending of Raiders of the Lost Ark, where they stick it in a box and hide it somewhere and no one's ever going to see it. That was the fear for all of us because we're all a little paranoid. “They don't want anyone to see this. They're just gonna buy it and hide it.” But we gave them the benefit of the doubt, and they gave us all cheques.

That's a good point that the psychology department, among others, can study it.

I think it's a great window. I don't know what type of focus they have in the psychology department—if they approach art therapy, for example. But even if they were just going to look at somebody with OCD, who created art about OCD, that says a lot, and we had twenty-five artists. That’s a great little slice of humanity right there to look at.

A psychological disorder can damage somebody's relationship with God because it’s intangible. How has that been hurtful or helpful for you?

Scrupulosity brought to me the idea of a vengeful God, a God of exactness, a God who was about justice rather than mercy. That was hard to live with. I tried to do everything with exactness and perfection, because that’s what we're supposed to do. There was no room for grace or forgiveness. Repentance is for people who are weak, it means that you obviously made a mistake and you're not worthy. It was all very frustrating and it diminished my relationship with Christ because Christ is all about grace, about trying again, as many times as you need to. I didn't understand that for a really long time.

It was during Covid—when we weren’t allowed to go to church or the temple—when I suddenly developed a really close relationship with Jesus Christ, because I had to learn how to let a lot of things go. I needed to learn how to sit in dissonance and disappointment and to be okay with it. Only Jesus Christ could provide that peace for me.

When I was doing the show, it was cathartic to relive those painful things that I felt no one understood. It’s hard to describe what you’re feeling because some things we obsess about are absolutely terrifying. It keeps you from living your life authentically. I was able to let go of a lot of things when I found Christ and His grace, when I was able to say things that needed to be said. I was finally able to drop the baggage that I've been carrying for decades, the obsession with perfection. I still sometimes worry but I also have better moments when I think, “That’s why I have Jesus Christ. I don’t need to worry about that. I’m a human being and I’m going to make mistakes.”

Approaching God is a mental activity for me. It has to make sense to me and that’s hard sometimes because I live in a forest of my own thoughts. Medication helps clear some of those trees so I can find a clear path. I know God and Christ can permeate any space – they are where I need them to be. And our Heavenly Parents are a lot more forgiving than we give them credit for, especially since their son is Jesus Christ. I need to accept that.

I now take it as a personal mission to intentionally look for God in other people. I’ve gone out of my way to see that we're all reflections or refractions of God, and I look for God in everybody. That perspective makes it a lot easier to talk with people I don't know, understand what they’re dealing with, and give them the grace they need. I’m a lot less angry, a lot more patient, I'm a lot quieter and calmer. It's been really good for me. It's a practice that I love because it's fostered really great friendships.

I need a village to feel sustained, I need friends. Being willing to be vulnerable tells other people it’s okay to be themselves. The more we are ourselves with each other, the more fulfilled we can be. Then it's easier to recognize God in others, when we are vulnerable. When we are willing to be vulnerable and say, “Hey, I see you. I don't understand everything about you, but I see that you are something really beautiful, and I want to celebrate you and love you and support you,” that’s when the world shifts for good. I love living that way.

Charlotte Condie is an artist/illustrator/designer based in the Atlanta metro area. She is originally from the Western states of the US and also lived in the Midwest. Her evolving creative experience and style spans more than two decades, multiple media, and three American regions. She has competed and won several chalk mural competitions, showed in a handful of galleries, and fills wholesale and retail orders. The bulk of her work currently revolves around dyed paper from old books, newspaper, sheet music, and various other used materials mixed with acrylic layers. When you buy her art, you are buying an original, handmade piece of American artistry.

Trina Caudle is an editor & writer focused on personal stories, and graduated from Western Oregon University with a BS in history & journalism. She and her family live in Washington DC.