This essay is dedicated to those who must journey through what Elder Holland once called the “battered landscape of the soul”—and to those who, though not suffering from mental illness themselves, journey alongside those who do.

If you are currently hurting, please remember you can always reach out—to friends, loved ones, or by calling “988” in the United States, any time, day or night.

As a cancer doctor, I frequently shepherd people toward death. This is a weighty, difficult, and beautiful part of my job. But one of the most deeply meaningful parts of this process is the way that those who love the dying nearly always regard them with honor, tender care, and even admiration. There is an intuitive understanding that cancer is not the fault of the patient and that the patient has almost always exhausted all of his or her moral and physical resources battling for health, hoping to vanquish the invading foe. When, finally, the patient gives up the ghost, a resigned peace often settles over those left behind.

I wish we could treat those who suffer from mental illness in general, and those who die by suicide specifically, like we treat those who have cancer. What follows is a theological framework for understanding the body and the brain that will allow for just that kind of compassion and kindness. My hope is that this piece will help those who suffer from mental illness—and those who love the sufferers—to see mental illness as a tragedy similar to cancer, an accident of malignant physiology, not an immoral or cowardly act. I believe this is what our theology teaches—but there are ways to misunderstand our theology that could suggest very nearly the opposite. And so, to get to what I think is the right understanding we need to begin by thinking about what a body is, what a body does, and what role a brain plays in all of this.

In medical school, I first learned this: the body is a machine.

In fact, this is a gross oversimplification. Doctors must first learn to understand the body mechanistically, but then later must learn to not see the body only this way. Still, a mechanistic conception of the body matters in learning medicine and can open to our view important truths about human physiology and function.

Our understanding of the functioning of the heart is the quintessential example of this mechanistic understanding. At base, the heart is a pump that powers blood through two parallel circuits: pumping blood to the lungs to pick up oxygen and then to the body to distribute it.

And as with anything else in human physiology, there are a thousand ways this can all go wrong.

When the pump of the heart begins to slow, many consequences can ensue: some patients see fluid accumulating in their legs and buttocks, leaving them feeling like the swollen marshmallow man. More ominously, others find their lungs filling with blood, robbing them of breath and the ability to exert themselves. Even more frighteningly, if the pump slows too much, the flow of blood to vital organs attenuates and all other organ function begins to deteriorate. In a person with a severely weakened heart—especially if that weakness happens suddenly, as is common after a major heart attack—the entire body can fail within just a few minutes—a testament to the heart’s irreplaceable and central physiologic function.

No wonder we refer to whatever animates any force or team as the “heart” of the enterprise.

All of these problems fall under the umbrella of what doctors call “heart failure.” If you sit in the workroom with cardiologists long enough while they’re caring for patients in the cardiac critical care unit, you will hear the term “heart failure” repeatedly. When we talk about a patient who comes to the hospital with “heart failure” what we are really saying is that the degree of the heart’s dysfunction is sufficient to cause problems in other parts of the body—whether doughy legs or drowning lungs or failing kidneys and ischemic limbs or all of these and more besides. In effect, the heart is “failing” enough at its physiologic purpose to cause noticeable physical problems.

What’s more, this paradigm—recognizing the effects of a “failing” organ—can be extended to the body’s other organs. A third-year medical student learns that a patient who comes to the hospital with a swollen belly, yellow eyes, and minute red “spider marks” on the abdominal wall is probably in “liver failure.” Likewise, a patient who has a potassium level well above normal, who is hardly able to stay awake, and has fluid building up in unexpected parts of the body may have “failing” kidneys. And a cancer patient whose malignancy is blocking traffic through the intestines—such that the person cannot eat without experiencing excruciating abdominal pain and vomiting can be said to have a “failing” gut.

But there is a conspicuous omission from the list of organs that sometimes “fail.” To our great societal and even moral detriment, never once during all my years as a medical student, resident, fellow, internist, or oncologist (now nearly 20 years combined) have I ever heard any doctor, in any setting, for any reason, refer to a patient as having a “failing” brain.

Now, in fairness to our field, maybe we don’t want to say that a person’s brain is “failing” because to do so would feel unnecessarily unkind. That is: if I tell a patient “your kidneys are failing,” they may be shocked or saddened but they probably will not be offended or consider it an affront to their dignity or morality. If, on the other hand, I tell a patient “your brain is failing,” that brings with it a very different connotation. But I sense that there is more going on. I think the real roots of our failure to talk of “brain failure” come from a particular philosophy of the body that exists in broader Western culture but that has also seeped into LDS culture and even into our understanding of our own religion, in ways I will explore below. At the end of the day, how we think about our brains says a great deal about how we think about ourselves—and thus this entire discussion has a great deal to say about our understanding of who we are, who God is, what the universe is like, and how we relate to the world around us.

I say this because there is one important sense in which the brain differs from the rest of the body’s organs: at least conceptually, the brain is the body’s seat for consciousness, agency, and will. As such, it occupies a unique and honored place among the body’s organs. We do not talk of the brain “failing” precisely because even a child knows that something distinguishes the brain from the heart, liver, or kidneys. No one supposes that anything happening inside the kidneys involves an act of conscious will. If I walked up to a patient whose blood contained too much sodium and told them that the problem was that they weren’t “trying hard enough,” I would be dismissed entirely or laughed out of the room. But any time anything goes amiss with the brain, we remain haunted by the prospect that that malfunction might be traced to inadequate will or even misshapen character, rather than a problem with that lump of tissue that is cradled so carefully inside the bony skull.

On the one hand, this is all as it should be. Unless we are to abandon ourselves to a complete form of physiologic and neurological determinism we must posit some role for will and consciousness in the functioning of the brain. That is, if we came to treat the brain “just like any other organ” then we would need to reduce everything from the works of William Shakespeare to the tennis of Serena Williams to nothing more than the random and unwilled firing of billions of synapses—this would be a form of brute biological determinism I would never want or be able to embrace.

Still, especially in religious circles, my sense is that we are rarely in danger of erring on that side of the spectrum. I have never sat in a church meeting, listened to the comments relevant to this discussion, and thought, “Oh no, here we go again, falling back into our old complete physiologic deterministic roots again.” No, that is not our cultural or religious issue, at least not in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Instead, what I often hear is strong suggestions that our mental health is the result of a conscious choice, as if depression, for example, could be overcome by choosing to just “think positive.” This all to say: I have sat in many church meetings—and in the hospital rooms and even at the funerals of many church members—where it seemed clear that we, as a people, had no sense for the brain functioning as one of the body’s organs, an organ that can fail just as surely as a kidney or a heart or a liver.

We may have some cultural allowance for this idea, but we seem to believe we know exactly which parts of the neurological and psychiatric disease spectra fall within this comforting penumbra—and which do not. So, for example, if a church member suffers a stroke, we somehow understand intuitively that this was a purely physiological problem. And, indeed, we are right. A stroke generally happens because a blood clot blocks a particular artery to the brain. When a blockage deprives a brain area of blood and thus of oxygen, that part of the brain dies and takes with it whatever function(s) are governed by that part of the brain. This straightforward mechanism allows us to be confident in viewing a stroke as a physical problem that arises because of an understandable problem in the body.

Strangely, however, while we are likely to feel nothing but sympathy for the person who suffers a stroke, our reaction may be entirely different when we hear of a person paralyzed by depression or when we learn of a friend who has died by suicide. In fairness, there is a difference between, for example, a stroke and depression. Whereas a stroke has a straightforward explanation—we can point to the affected region of the brain on an MRI—there is as yet no such straightforward explanation for depression and similar ailments. Yes, it’s true, we can discuss fancy-sounding doctor words like “neurotransmitter imbalance” or “selective serotonin deficiency,” and we sometimes prescribe medications meant to ameliorate just those problems. But the truth is that even when we do so, we are kidding ourselves if we think we have anything like a holistic understanding of the causes of depression or how to fix them. This is demonstrated by the fact that those medications that are meant to help with these supposed underlying problems have at best a mixed track record of efficacy—there is significant evidence that they are widely over-prescribed, and many patients try long and rotating lists of different medications and yet never discover anything that brings even significant, let alone complete, relief.

But even if we recognize that our understanding of the causes of psychiatric illness remains incomplete and muddled (and psychiatrists join me in this view), we must, too, recognize that this incomplete understanding does not account for our propensity to freight psychiatric illnesses with the burden of moral opprobrium. After all, nearly all of us have precious little understanding of how the kidneys or liver or heart go awry, and yet we intuitively understand that the failure of any of these organs reflects a nature bent toward entropy—not the consequences of a lack of will or moral fiber. From a gospel perspective, I would argue that the difference between our approaches to these various health problems is that, as church members, while we intuitively accept a mechanistic understanding of the body, we nonetheless believe that we are constituted of an eternal core, and we recognize that the eternal part of us resides—in some way none of us can articulate or understand—“inside” of the organ we call the brain.

Of course, likely none of us would argue for a simplistic notion of this kind of biological/spiritual dualism—something akin to a “Casper the friendly ghost” taking up residence inside the physical brain—but we still have this persistent understanding that whatever it is that constitutes the eternal self must live “in the brain” if it “lives” anywhere at all. And, in truth, however crude our understanding of this question, in some ways we are not that far behind the most sophisticated neuroscience in this sense: for all the deep insights we have gained about neurons, synapses, neurotransmitters, and all the rest, we have at best a woefully incomplete understanding of what “consciousness” even is, what it is made of, how it arises, or what becomes of it when we die. It is a confounding aspect of our neurobiology that we cannot explain or deconstruct the phenomenon that constitutes the central core of what it means to be human.

That all said, however, what remains true—and what is vitally important for our conception of ourselves, of God, and of our own goodness and even eternal destiny—is this: the brain is an organ. And, as such, it can fail just as surely as a heart or a liver or a kidney.

This is clear to me as a doctor precisely because I see the consequences of the brain failing all the time. I saw it in my grandmother who died of Alzheimer’s—in the years before her death, the accumulation of fibrous tangles in her neurons had entirely robbed her of her personality. I see it in patients in liver failure, who, unless the underlying problem is addressed, become first pleasantly loopy and then entirely comatose because the failing liver cannot clear toxins from the blood and the resulting buildup renders the brain incapable of normal function. And I even saw it once in a patient I cared for in the hospital who lost her glasses and her hearing aids at the same time and who, in a foreign environment and robbed of the ability to see or hear, became so agitated and delusional that she nearly required physical and chemical restraints until her husband came from a far distance days later and let us know what was the problem—her mental status returned to normal within an hour of having back her glasses and hearing aids. This may seem a strange example but I use it for this reason: in this patient’s case, there was no issue with the rest of her body–no infection, no worsening of her cancer, no hormonal imbalance—the only thing wrong was that her brain was deprived of its customary ability to accept and interpret sensory data.

This all matters for one simple but foundationally important reason: because what we term “mental illness” is also a form of “brain failure.” That is, depression and schizophrenia and bipolar and all the rest are physiologic issues as surely as broken bones and failing kidneys are. This realization allows us to respond with empathy and compassion—rather than disdain and condemnation—when we see the brain “failing” in someone we love or even when we begin to see signs of such “brain failure” in ourselves. This is not to suggest we abandon the importance of good mental hygiene, that we neglect the importance of optimism, or that we pretend we have no role in how the brain functions—any more than we would suggest that we abandon exercise or a heart-healthy diet. Rather, it is just to point out that while we may be right in intuiting that my identity in an eternal sense is intimately interlaced with whatever it is that happens in and because of the brain, and while we can continue to honor the need to approach those happenings with moral seriousness, we can still approach mental illness and all its attendant trappings with kindness and compassion. Even though we do all we can to keep ourselves mentally, psychiatrically, and neurologically healthy, we can still extend grace and space to those around us—and to ourselves—when those best efforts do not produce the effects we wish they did.

All of this brings us to a greater physiological understanding of why Elder Holland would write:

But today I am speaking of something more serious, of an affliction so severe that it significantly restricts a person’s ability to function fully, a crater in the mind so deep that no one would responsibly suggest it would surely go away if those victims would just square their shoulders and think more positively—though I am a vigorous advocate of square shoulders and positive thinking.

Similarly, President Reyna Aburto wrote:

Black clouds may also form in our lives, which can blind us to God’s light and even cause us to question if that light exists for us anymore. Some of those clouds are of depression, anxiety, and other forms of mental and emotional affliction. They can distort the way we perceive ourselves, others, and even God. They affect women and men of all ages in all corners of the world.

Elder Renlund adds much needed clarification:

There is an old sectarian notion that suicide is a sin and that someone who commits suicide is banished to hell forever. That is totally false. I believe the vast majority of cases will find that these individuals have lived heroic lives, and that suicide will not be a defining characteristic of their eternities. I believe Heavenly Father is pleased when we reach out and help his children. But we shouldn’t underestimate the importance of the church community coming together to help each other through this life.

What strikes me so forcefully about these quotes, taken together, is the degree to which they remove from the individual the blame or moral onus for the havoc that mental illness wreaks on those who suffer from it. None of these authorities speaks, per se, about the brain as an organ, but it seems clear to me as a physician that that is the fundamental philosophical shift that underlies the transformation they are implicitly and, in the case of Elder Renlund, explicitly calling for.

In addition to doing everything within our power to help those whose brains will not cooperate (offering resources, a helping hand, friendship, safe harbor, and connection to professional help), I invite us to reframe how we think about what is happening inside of them so that instead of seeing a flagging spirit or an inadequate will, we picture a brain that is simply malfunctioning, like a heart that can no longer pump, or a liver that can no longer filter. In the same way we would never suggest to a patient with heart failure that they just “try harder” or “breathe better,” can I suggest that we consider treating those whose brains are betraying them with an ever-greater outpouring of help, compassion, aid, and love? I was moved to better understand the deep need our culture and religion have for just this kind of better understanding some time ago when reading a memoir written by a church member who, after an early life defined by clear thinking and no significant emotional problems, was diagnosed in early adulthood with bipolar depression after a series of devastating episodes that upended his own life and those of his family members. After an entire book describing what the episodes themselves were like and the effect they had on himself and those he loved, as well as how he was treated (especially at church) as a result, he summed up by writing this:

Like the lepers of old, the mentally ill are assumed to be worthless to society and, in most ways carry a net negative in their personal balance sheet. In the church, they are never called to a position of responsibility, because they cannot be relied on. They are never asked to speak to a group, because they will freeze in the situation. Mental illness is so debilitating in society that, in a very real sense, its victims are shunned like the lepers of old.

He goes on to ask all of us:

So what do you do with the lepers of today, the bipolar? How do you think about them? Do you participate in gossip about them? Do you make judgments about their behavior? How much do you know about them really? Do you find ways to include them? Do you understand when they do not want to be included? Do you probe into personal areas that are none of your business? Are you part of their support structure or part of the problem yourself? How do you react to the lepers of today—the mentally ill?

I believe his statements, his biblical analogy, and his comparisons deserve our careful and meditative attention. His condemnation of our thoughts and behavior is not without merit and his queries can become a powerful catalyst for reflection and change.

I co-host a podcast where we discuss finding meaning in the practice of medicine, and we recently hosted Clancy Martin, an author and philosopher who has been haunted by a desire to consider suicide since he was six years old. While on our program talking about his battle to keep himself alive, Mr. Martin said,

It is true that the way the Abrahamic tradition has been received and even revised, we have this tendency to blame ourselves for a whole host of things that go wrong in our lives . . . [But] even within the Abrahamic tradition there are so many great thinkers, leaders, and philosophers who will tell you, ‘no that’s not the right way to think about it, you can have, and ought to have, a disposition toward your religion, toward your spiritual experience, such that it’s there precisely to help you with those most difficult challenges, with places where you encounter obstacles, precisely the place where you would like to blame yourself is precisely the place where you should be applying spirituality as a medicine to help you accept yourself, nurture yourself, take care of yourself.

And in this view of the mind as something entirely unlike the rest of the body, we see, finally, the full theological consequences of our misperception. Perhaps this is a place where some of our most cherished beliefs—the co-eternality of the soul, the importance of agency, the reality of spiritual apart from physical existence, and on and on—have been hijacked to make us believe (often implicitly, sometimes explicitly) that mental illness is a moral deficiency, and that suicide, especially, is a scarlet sin.

I think a person’s understanding of the harm these misunderstood bits of theology can cause largely rests on whether they—or someone they love—has experienced the ravages of mental illness firsthand. It is easy enough, after all, for those not acquainted with this particular “battered landscape of the soul” to assume that depression, for example, is simply a failure to follow the commandments to have hope and to be believing. I think it is hard for those unacquainted with depression or similar illnesses to comprehend that the problem is not that the person is not choosing to be happy but, rather, that the very idea of happiness has fled from the soul as surely as warmth flees when winter descends. It is not just a lack of happiness itself but the lack of the very ability to imagine being happy, at least temporarily. Those who have suffered depression themselves or who have journeyed with one they love through that travail know just how much it can sting when a classmate at church or even a church leader acts as though this could all be overcome through better choices or healthy living—even if those words spring from understandable theological assumptions.

But we have at hand other theological resources, equally deep, that offer a very different spiritual framing. We can look to verses like Lehi’s teaching that there “must needs be” an opposition in all things, asserting that entropy and adversity are woven into the fabric of the universe. To my ears as a doctor, these suggest that perhaps we need not be surprised that the same symphonic synchrony that allows for fruitful functioning of a working brain can at times become corrupted, leading to states as devastating and varied as bipolar depression, schizophrenia, and major depressive disorder. Just as cancer is woven into the very biologic processes that allow a human to grow into a human, the seeds of mental illness lie dormant in what allows us to have functioning brains—and even transcendent consciousness—in the first place. In this one case, “there must needs be an opposition in all things” says, to this doctor, anyway, that even brains that function beautifully in most circumstances can malfunction tragically, chaotically, and inexplicably in other settings. The seeds of mental illness are planted in each of us, and we never know when they will sprout. Knowing this can allow our community to bring mental illness out from the shadows—it can invite us to talk of a person hospitalized after attempting suicide not with the hushed discomfort we reserve for those we believe are doing something shady or shameful, but with the hushed admiration we have for a person who stumbles halfway through a marathon. This understanding allows us to see things as they really are, and to muster compassion and veneration for those who are laboring under a weight most of us can only imagine.

Now, as I wrap up, I want to pause to clarify one vital point. Though I’ve spent pages here explaining why we need to understand that the brain, too, is an organ like the heart or a lung, we must also recognize straightforwardly that the brain is also unlike any other part of the body. Yes, it is an organ. And, yes, it can malfunction. And, no, we should not impute to those who suffer from mental illness culpability for the ways in which the brain can break. Yet, it is simultaneously true that while the brain is an organ, philosophers also conceptualize of something called “the mind,” which serves as a sort of bridge between the physical, material, anatomical structure that sits behind our ears and the ineffable, indecipherable, unquantifiable substance we call our “spirit.” What exactly constitutes a “mind,” or what we mean by “consciousness,” has been debated since at least Descartes, and remains one of the great mysteries at the overlap between religion, philosophy, physics, and biology. The resolution of this mystery lies far beyond the scope of this paper—but acknowledging the existence and importance of the mystery matters. Still: the existence of the mystery merely underlines the importance of affording every benefit of the doubt to those who wade their way through the troubled and murky waters of mental illness.

And then, with a sense of this mystery and these strains from our theology firmly in hand, we can look to a moment in our scriptures that means more to me than perhaps any other precisely because of what I believe it tells us about God’s view of and response to those who suffer—from mental illness, particularly, and from the myriad other trials life brings, generally: the encounter where Enoch sees God weeping and finds, when he asks God why, that it is because God’s heart has been filled to overflowing to see the suffering of his children. What I extrapolate from this verse in the setting of our discussion here is this: Because the hearts of our Heavenly Parents beat in tune with ours, how could our suffering lead to anything other than their weeping?

What follows the passage is hardly surprising: “And it came to pass that the Lord spake unto Enoch, and told Enoch all the doings of the children of men; wherefore Enoch knew, and looked upon their wickedness, and their misery, and wept and stretched forth his arms, and his heart swelled wide as eternity; and his bowels yearned; and all eternity shook” (Moses 7:41).

For me, this description means that when we come to understand the brain as an organ, and mental illness as a “failure” of physiology—but not of character or morality—then we can move past the ingrained temptation to condemn those who suffer and die from mental illness and we can, with Enoch, allow our own hearts to “swell wide as eternity.” In this case, a clearer understanding of physiology can better equip us to be Christlike because it removes from our path “philosophies of men” that have become mingled with our scriptures in a way inimical to the health and flourishing of the body of Christ.

To receive each new Tyler Johnson column by email, first subscribe to Wayfare and then click here to manage your subscription and select "On the Road to Jericho."

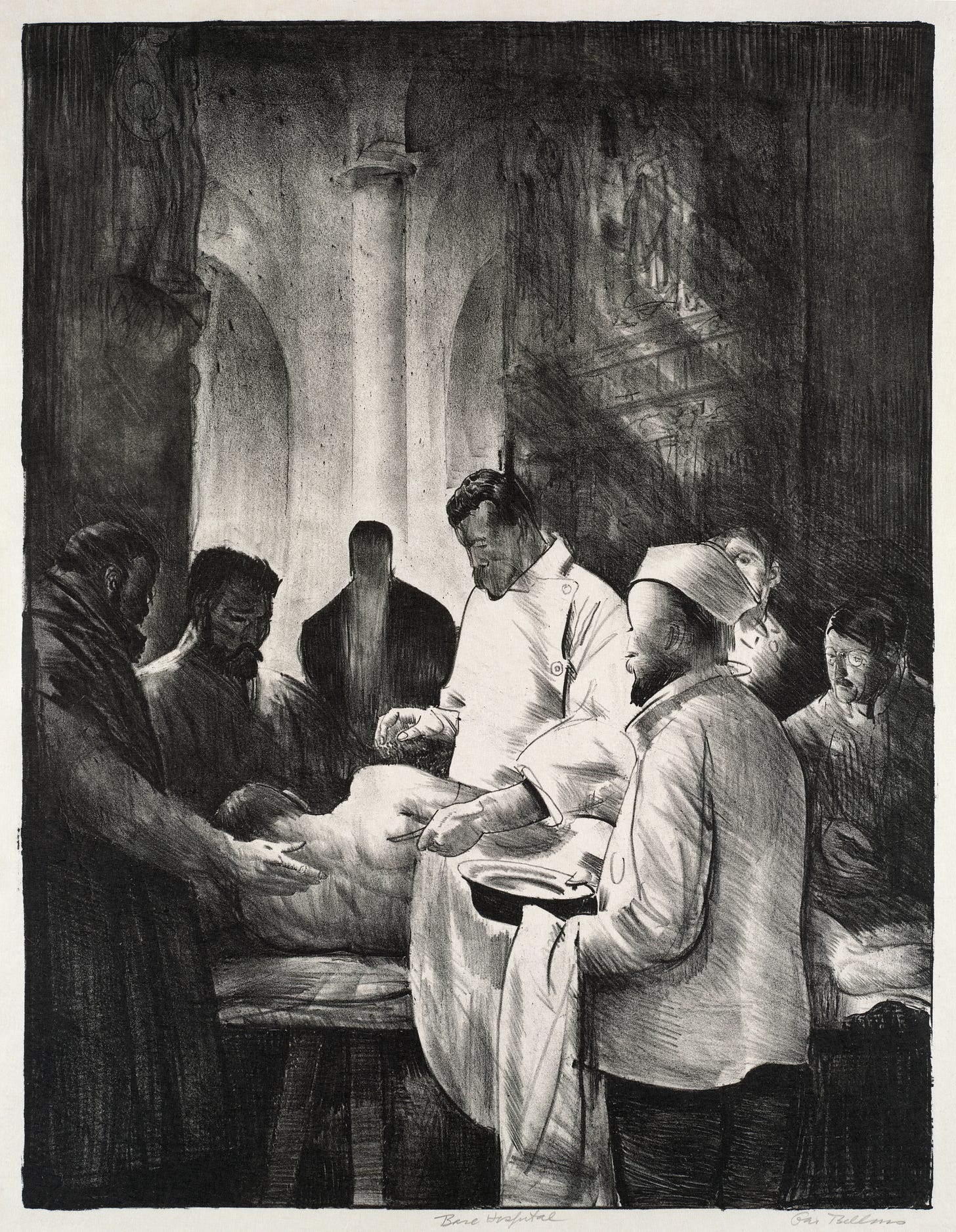

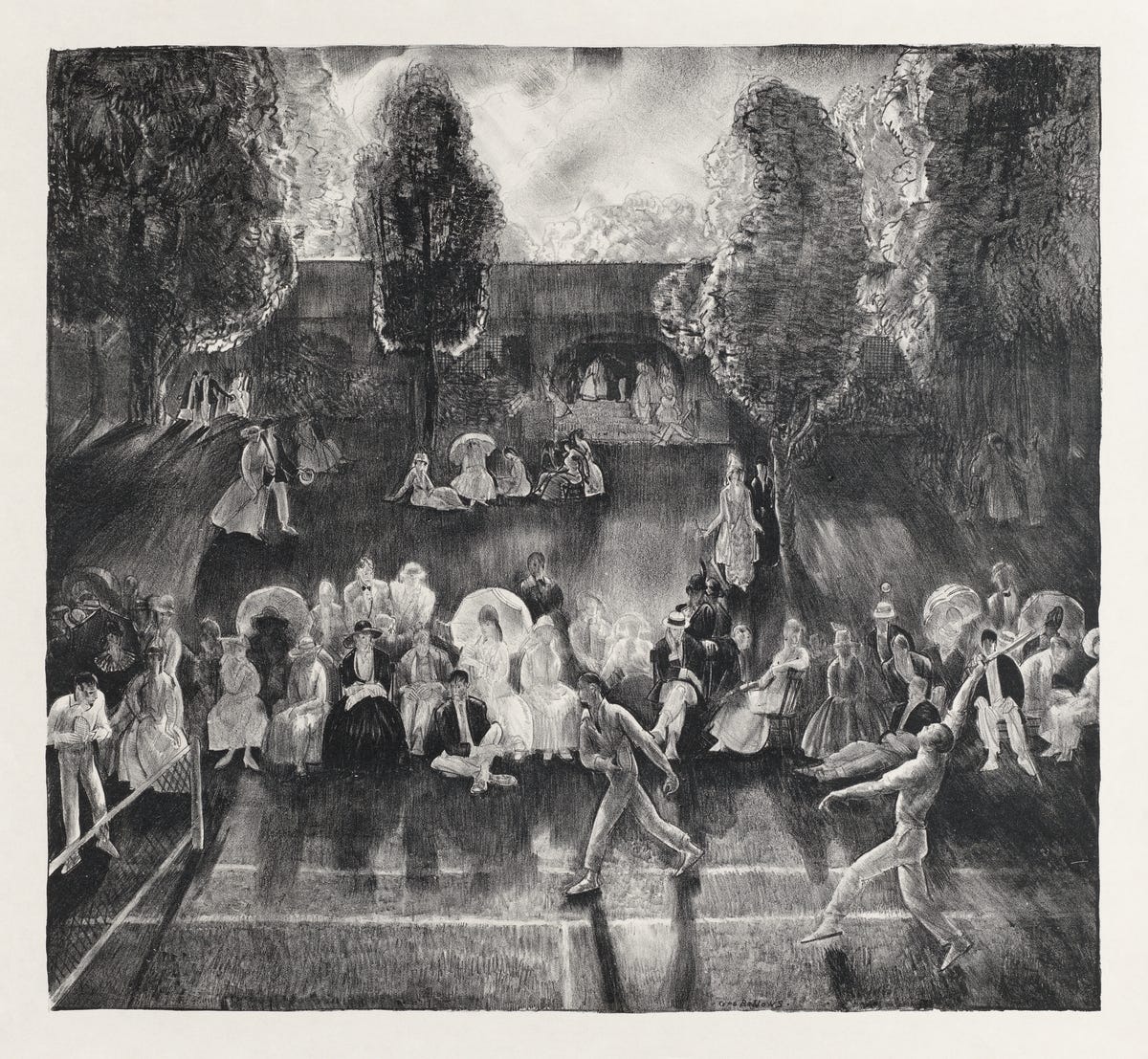

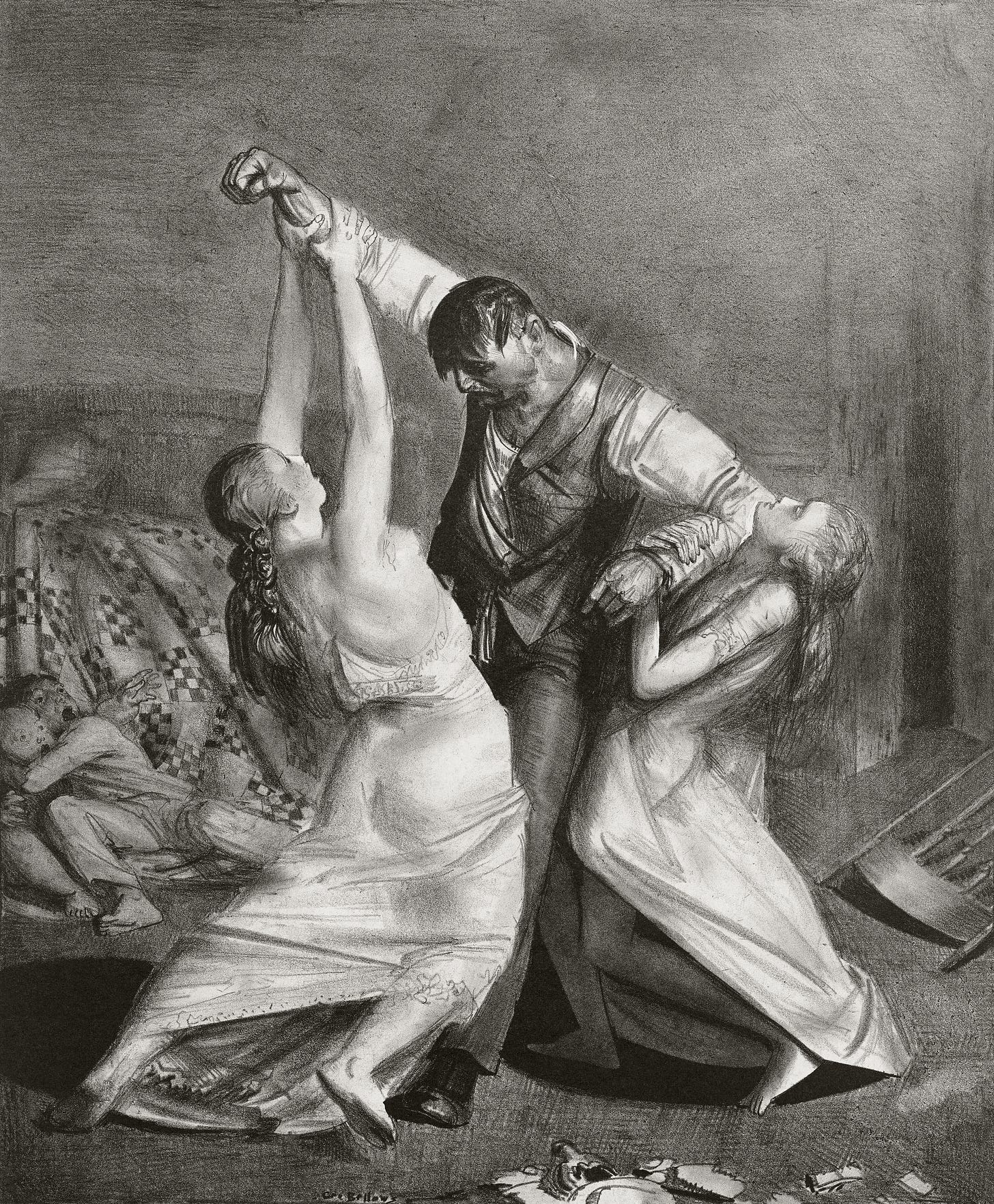

Art by George Bellows.

This was absolutely illuminating. Thank you. My father in-law died by suicide, a close cousin attempted it unsuccessfully but was left with permanent brain damage, my brother attempted suicide, and my my sister in-law has attempted it several times; one of my best friends died by suicide; my husband has had a lifetime of wrestling with anxiety; and my three sons have wrestled with OCD, depression, and anxiety to the extent that it brought two home early from their missions leaving one suicidal. Through love, my own mind has descended with them and so I know the things you explore here are true. There hasn’t always been understanding. We have had some of that “just choose to be happy” coming from those who do not know. But I am grateful that, not just the general public’s perspective of mental illness, but our own Church culture, is becoming more compassionate and more accepting and more humble about these things we know very little about.

I loved what C. S. Lewis had to say about the struggles of an uncooperative body: “…do not despair. [God] knows all about it. You are one of the poor whom He blessed. He knows what a wretched machine you are trying to drive. Keep on. Do what you can. One day (perhaps in another world, but perhaps far sooner than that) He will fling it on the scrap-heap and give you a new one. And then you may astonish us all—not least yourself: for you have learned your driving in a hard school.”