Picture the pain as an ocean wave.

It was advice I was given a few weeks before giving birth to my first child. When you’re pregnant, there are well-meaning people—family and strangers alike—who will pile all sorts of unsolicited advice on you. It comes with the territory, along with restless nights, daily Google searches like “Accidentally swallowed watermelon seed, bad for baby?” and instinctively cradling your growing belly more times than you can even count.

So many of the comments people made didn’t register with me, but this one did.

When you’re in labor, picture the pain as an ocean wave, rimmed with brine and froth. The wave creeps up gradually at first, so slow that it’s almost unrecognizable in the beginning. This part doesn’t last long. Too soon the pain will advance and swell, crashing and cresting with almost unbearable intensity–and yes, it will feel unbearable. You will lose yourself to it, so mindless with pain that it is difficult to know how much time passes. At some point, the wave will recede in twirling, salty eddies, as gradual as its arrival. The silence at the calm shore in between waves of pain will feel blessed. Sacred, almost. The wave’s return is inevitable, so don’t try to fight it.

Ride it.

I found this advice extremely effective. The pains of my labors felt necessary, even purposeful. Riding those waves has brought me three children, each emerging in distinct epochs in my life. Trying to effectively encapsulate the experience of motherhood is like trying to capture a mountain in a butterfly net. But I will say this: in the midst of caring for my young children—brushing hair back from a bath-clean forehead, practicing the “th” sound with a new reader, watching my newly walking son navigate a riverside path—I realized that the act of birthing my children began shaping not only their identities, but a new facet of my own: I was a creator.

Soon, this need to create began to manifest itself in another way. My fingers itched; time felt finite in a way it never had before. My baby was growing so fast—at times it seemed like her face was changing every day—and this spurred me on to an urgency to remember all of it: the midnight feelings of sleep-deprived despair, the relentless tangle of my feelings about motherhood, the joy that would sometimes stop my breath. My restlessness grew, a wave that I rode to conclusion: I had to get this down on paper. I started to write. Snippets of ideas would come to my mind as I nursed, and I would awkwardly arrange my daughter as she fed so that I could type on my phone with one hand. I’d scribble key words on snatches of paper and write late into the night, desperate to remember the moments bright enough to break through the foggy haze of those newborn days. The seedling habit took hold; it grew and spread roots. Soon I was writing every day, channeling as much as I could somewhere more permanent than my brain: somewhere to remember.

Riding the ocean wave; writing the ocean wave. Dual acts of creation, the former accompanied by guttural screams in hospital rooms, the latter by late-night hush in a sleeping house. As significant acts of creation, both require pain.

Trying to live a creatively fulfilling life while also caring for three children is difficult, and has summoned from me reservoirs of strength and endurance, mimicking in a very small way actual labor. There’s a persistent myth surrounding artistic effort which posits that creativity is effortless and instinctual. That if you have to struggle to pull beauty and order from this world of chaos, then you’re doing it wrong. I certainly thought this, and found myself balking at the waves of critiques, edits, revisions, re-drafts, and rejections that accompanied every single piece I wrote. Maybe I’m not cut out for this at all, I’d think to myself. Maybe I should give up.

What I have since come to realize—and it was a long and slow realization, a realization I should have made months, maybe even years before I actually did—is that anyone serious about creation is going to suffer. “Suffer” sounds very melodramatic, I know, and yet I cannot think of a better way to say it. Revisions, rejections, critiques, despondency, imposter syndrome: they are all a normal part of the creative process.

Perhaps, like childbirth, creation doesn’t even happen without them.

My experience with writing is cyclical in nature, and by that I mean that the process of writing has only intensified my craving to write more. “Craving” might not be the right word, although neither is “hunger.” Both feel too overused, too drained of meaningful scope, and neither really encapsulates what I feel. All I know is that it is difficult to ignore my desire to propel raw ideas forward into something fuller. To harness nascent creative energy and see where it might lead. Bringing forth into the world something that you made yourself is invigorating, but frightening. At the heart of creation lies hope, though, and that hope is the site of grace: even if much of my writing is for myself alone, I take joy in the experience of growth.

Waves retreat, waves crest. I’ve been revising this piece over several weeks, in between unloading the dishwasher, wiping peanut butter from my son’s cheeks, and finding penny-sized scraps of paper from an art project that was supposed to be cleaned up three days ago. I can always stand to be more patient with my children, to parent slower, to feed them fewer Costco chicken nuggets and more apples.

Larger, more significant swells overwhelm my life, too: the winds are incalculable and overwhelming, and the sea is inky and opaque. I’m neither stoic nor saint, and riding the wave doesn’t always look the way I want it to. Sometimes I tumble—hard. Creation always carries the risk of failure. The outcome is always uncertain. Attempting to ride a wave, all while knowing it could be the one that finally topples me, is the risk of a lifetime—but it’s a risk I’d like to take.

Waves of uncertainty and pain are inevitable. Making peace with this truth could mean following the advice I was given years ago. The wave’s return is inevitable, so don’t try to fight it. Ride it.

Shayla Frandsen is an MFA student at BYU. Her writing can be found in Exponent II, Dialogue, JAKE, Beaver Magazine, and more.

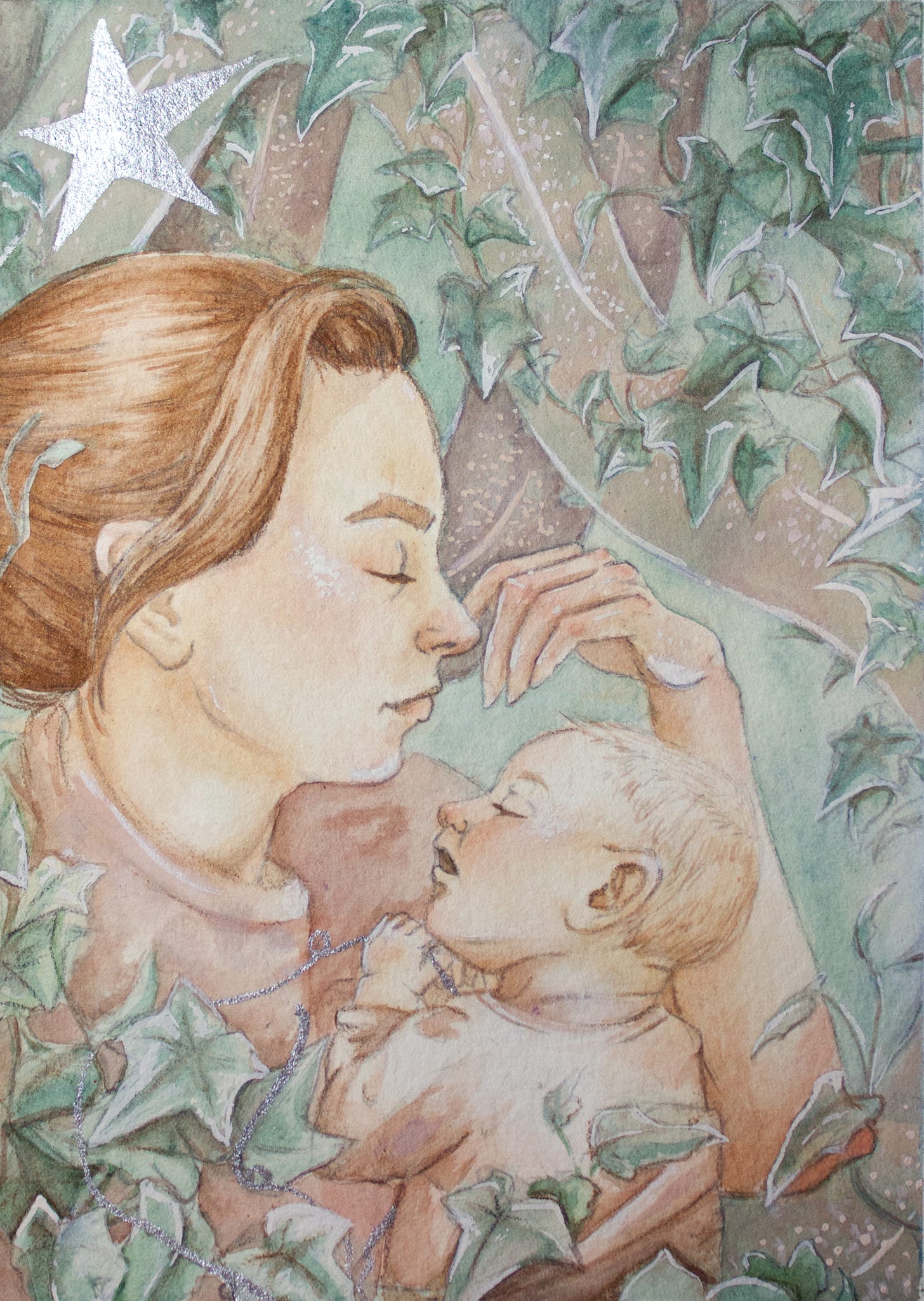

Art by Lauren Walke.

Editors Note: With 2023 about to begin, read Benjamin Peter’s call to rethink the way we approach New Year’s resolutions.

What is life without risk? What is life without letting yourself unfurl into the future? I love that your experience of motherhood unlocked and enhanced your ability to leap into creativity (as much as it constrains and guides it as well--both the tether and the wind that allow a kite to fly).

Thanks, Shayla. As a first-time parent this year and a witness to my wife's intense labor, I really appreciated and benefited from this piece.