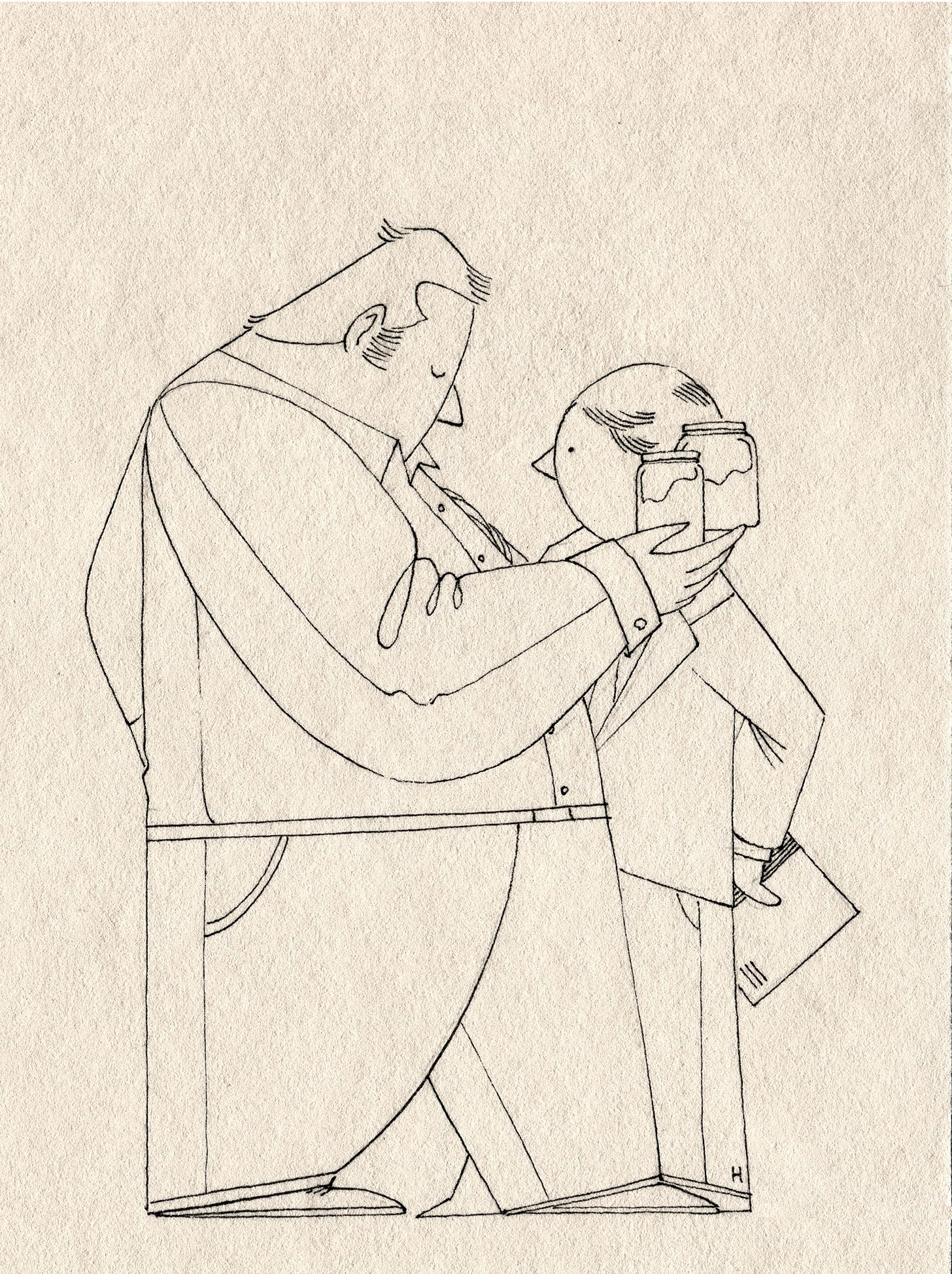

Heshel was with Bishop Levy in his office one week, going over the afternoon’s appointments, when Beynish walked in, carrying a shopping bag, from which he unloaded seven large jars of schmaltz.

Bishop Levy was surprised to see Beynish there. The man rarely came to the foyer, let alone to the bishop’s office. “What can I help you with?” the bishop asked.

“I’ve been so stressed, bishop,” Beynish said, “ever since I lost my job. And now, things have started to spin out of control.”

Bishop Levy was surprised. He prided himself on keeping up with the ward’s needs. “I’m so sorry to hear that,” he said. He motioned for Heshel to go. There was no guarantee the famously distractible secretary would come back, but what was the calling of a bishop other than a juggle between today’s lost sheep and the next ones to wander? “Let’s talk about how the ward can help.”

But Beynish put a hand on Heshel’s shoulder before he could get up. “That won’t be necessary, bishop. I’ve only come to pay my tithing, and then God will bless me. If it’s the same to you, I’d rather leave the ward out of it.”

Bishop Levy was surprised once again. Beynish hadn’t paid tithing in years. “It’s true that God will bless you,” the bishop began cautiously, “though perhaps through an employment specialist—”

“Why would I need an employment specialist?” Beynish interjected.

“—or, when times are hard, some fast offering funds,” Bishop Levy continued. Best to get all the options on the table first, then let Beynish think them over. One way or another, the Lord helped those who helped themselves. And at every ward party he had bothered to attend, Beynish had certainly helped himself. It wouldn’t do if he walked away now, too proud to accept any assistance. How long, Bishop Levy wondered, had the man gone without a job before coming?

Then his brow furrowed. Bishop Levy was neither the wisest nor the quickest man in Chelm, but something about this situation didn’t add up. “Beynish,” he thought to ask. “If you don’t have a job, what tithing would you need to pay?”

“I told you,” said Beynish. “I’ve been so stressed! I can’t stop eating. And then I got on a scale. I won’t tell you how many kilos I’ve gained,” he added, then waved a hand sadly toward the jars of schmaltz, “but you can do the math. That’s the same as one-tenth of my increase. Just like it says in the scriptures.” Then Beynish looked at Bishop Levy. “Now be honest: is it true that if I pay tithing, the God of Israel can help me lose weight?”

If the Lord of Hosts was in that business, Bishop Levy thought, there would hardly be any need for a ward mission plan. Caring for the soul was quite a hard sell when you contrasted it with how easily people fretted over the size of their bodies. He tried to think of a scripture that had something to do with what Beynish was suggesting, but most of the verses that came to mind weren’t helpful. Nothing about diets. He wasn’t sure the word thin even appeared in the scriptures. And there were so many verses about the opposite: feasting on the word, feeding sheep; about free milk and honey, or enjoying the fat of the land. God was like a Jewish mother. Eat, eat, eat, and still: “you have been weighed in the scales and found wanting.” Wasn’t there any allowance for people who looked in the mirror and didn’t like what they happened to see?

Bishop Levy nodded slowly. “I think there’s something on the subject,” he said, “in Ecclesiastes.”

“Wonderful!” said Beynish. “I knew we were blessed to have the Book of Mormon!” And then, whistling to himself, he walked out of the door.

Bishop Levy sighed. If the blessing didn’t appear, he hoped Beynish would at least come back to complain. It was nice to see him in this humble house of God, even if he did treat the door as if it were built for revolving.

While the bishop was lost in thought, Heshel glanced down the hallway and noticed that Feiga Cohen had come early for her scheduled meeting. That was not likely to be a quick visit; she would have a thing or two to say! And so Heshel would get a little free time to look around after all. First, though, something had to be done about the bishop’s desk. Heshel managed to gather up four of the schmaltz jars in his arms; Bishop Levy grabbed the other three and they walked down to the financial clerk’s office to drop them off.

It’s interesting, Heshel mused, how different people paid their tithing. Yossel’s always came from his net. And Beynish’s was definitely gross. The beauty of the gospel was that you could teach people correct principles and, whether they listened or not, in the end they would rule themselves.

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

Artwork by David Habben.

To order the complete Tales of the Chelm First Ward, click here.