Believing in Silence

“Do you believe in God, and, if not, what would have to happen for you to believe?” is the question that was hurled at me from across the table by a stranger at a recent dinner party. “Oof,” I thought, because even after 11 years of studying and writing about religion, I still don’t really have easy answers to these kinds of questions. But I know what a 20-something-year-old is supposed to say in such situations, surrounded by other 20- and 30-something-year-olds in Cambridge, Massachusetts: “No, I don’t believe in God.” Easy.

I’m not an atheist. In fact, I actually do think there probably is a God, for two reasons that are admittedly unconvincing: 1) I have both personally met and read the accounts of many people who have clearly experienced something I have not, which they describe as God; and 2) as the extraterrestrial enthusiasts say, “I want to believe.” I want to believe there is something more than the fault-ridden world we currently find ourselves living in. But there are two reasons why I don’t think this constitutes belief in God.

First, when I do read or hear people explaining the nature of their belief in God, it is usually described as a deeply felt experience as opposed to a purely intellectual or abstract concept. As I said, I have not—to the best of my knowledge—had such an experience. The second reason I do not claim to believe in God is that the assumed meaning of “God” is often a very narrow one: it is the God who created the universe, presides over it, resides vaguely somewhere above the Earth, is anthropomorphic, is male, is white, and is how God has been classically depicted in the West. For many nonreligious people in the United States, this is the God that they assume most religious people do believe in and is a God who, often for good reasons, they cannot believe in. Neither can I.

The problem is that the assumed consensus definitions of things like “God” and “religion” are so narrow that they discourage many people from considering that religion can be about much more than God, that God is much more than Western Christendom, and that there are many ways one can derive benefits from religion that do not necessitate belief in God. When I attempt to both think about or connect with God, I am met with silence. While this used to disappoint me and once felt like a personal weakness or failure, I’ve come to recognize this silence facilitates listening and, in my case, even healing. For me, what has proven most valuable about religion is not the concept of God itself or any specific beliefs about God, but rather, religion’s power to generate meaning that can help us live better lives. Religion can express what is otherwise inexpressible, thereby allowing us to resolve or at least humbly accept and coexist with life’s most perplexing mysteries, questions, and experiences.

While I was in college, I was often asked why I was studying religion. I suppose it surprised a lot of people, since I was not a traditionally religious person. My brother and I were raised Jewish by my atheistic Jewish father and my devoutly Catholic mother, which was weird and confusing. But I really did consider myself Jewish in childhood, during which religion was an important part of my life. Then, when I was about 11 years old, we just abruptly stopped going to synagogue and our observance of Jewish customs at home gradually petered out. Why my parents pulled us out of all that is a topic for another day. The point is, I went from having a very clear religion to no religion very quickly. At the time, it didn’t bother me. I loved science and was beginning to inherit the idea that we science people weren’t supposed to like religion anyway. There was no reason for me to think I would ever return to religion in any meaningful way.

I have given many different answers to the question of how I ended up studying religion. The real reason is this: I was a college freshman suffering from undiagnosed bipolar depression. I had no idea what was happening to me. For several years, it never even crossed my mind that I might be mentally ill. I just knew there was some part of me that was deeply disturbed and, for some reason, reading religious scriptures, novels with religious themes, and scholarly writings on mysticism helped a bit to silence the gloomy, despondent part of my mind. These positive experiences with the intellectual side of religion encouraged me to experiment with the more practical elements as well. During my college years, I wanted to believe in something—and not just believe, but really have some kind of deep profound spiritual experience because that’s what I thought it would take to set me free from my internal hell. I briefly dropped out of college to spend two months at a hippie retreat center and learned tai chi, which I kept practicing for the next 6 or 7 years. I tried meditating. I tried praying. I tried psychedelics. I didn’t just casually try these things once or twice. I committed to them each for long stretches of time. Still, I felt nothing. Just silence. And at a certain point, being in the presence of others who did profess to feel something powerful in these settings made me feel so guilty that I had to just stop. My inner silence felt like a disrespectful defiance of the intended purpose of these sacred spaces, where people came to connect with something transcendent.

However, there was one experience early on in this period of spiritual wanderlust that helped plant the seeds of future realizations about the religious significance of silence. At age eighteen, I got to take part in a Native American sweat lodge. In very simple terms, a sweat lodge involves a group of people sitting inside a thickly insulated tent that is filled with steam, raising the temperature to an extremely high level. In my case, the whole event lasted about three hours. There was drumming and chanting and invocations of spirits. It was neat, but didn’t make me feel anything special. I just felt hot and sweaty. I had a hard time breathing. But I wanted to tough it out. The time within the tent is meant to represent a period of gestation leading up to a symbolic rebirth that involves crawling out of the tent on all fours. I didn’t want to prematurely birth myself. And I’m very glad I didn’t.

As soon as I crawled back into daylight, I was overcome with the deepest sense of silence I’ve ever felt. For the rest of the day, I didn’t speak a word to anybody, I didn’t eat a thing, I didn’t even drink any water (even though I had just shed what felt like about 5 pounds of sweat). None of that was done purposefully or consciously. I just felt a profound sense of needing nothing, wanting nothing, thinking nothing. I didn’t interpret any of this as a spiritual experience and I still don’t, though I can understand why some people might be inclined to do so. To me, this was in a sense the exact opposite of a spiritual experience: it was an experience that brought me down to Earth completely, temporarily washing away my anxious need to apprehend the spiritual.

I’ve always found comfort in silence in a way that’s not so dissimilar from the way people have described God to me. But it took some time for me to recognize that. In the meantime, my engagement with religion in college did not heal me, but it kept me afloat. And I kept holding out hope for the possibility of some spontaneous religious experience that would zap me back into living life with rose-colored glasses.

That never happened. What did heal me, during my senior year of college, was medication. Almost instantly. Like, pretty amazingly so. If ever there was a poster child for the merits of a pharmaceutical approach to mental illness, it is I. It certainly took a few years to arrive at the optimal combination of pills and get to a point where I became essentially asymptomatic, but even that first two weeks on medication was like night and day compared to where I was at before. Grateful as I was, though, it left me feeling a bit uneasy. The whole time I was studying religion, it felt like I was traveling down my own self-paved road toward deliverance. But then this other thing swoops in and saves the day. Once more, religion and theology were beginning to feel strangely obsolete and I had to figure out what role these things could play in my life going forward, if any.

So, I went to graduate school at Harvard to study theology and see if I could use what I learned to help others. During that time, I kept up with my personal experiments. I tried going to church. I tried working at a church. I tried working as a chaplain. I tried (unsuccessfully) to meet the elusive guy who ran the Daoist temple in the quiet wooded area about thirty minutes west of Boston. I tried to immerse myself in a Baha’i community. I tried these things because, despite being mentally healed, I still felt spiritually impoverished. I still wanted to have that direct religious experience that would instill in me some form of genuine belief. I wanted life to feel meaningful rather than just tolerable, and I didn’t want this thing, which was such an important part of my identity for so long, to simply die.

There’s a voice in my head that periodically whispers, “Why are you still messing about with religion if it makes you feel nothing?” I am then reminded of something my tai chi teacher used to say: “Tai chi is like brushing your teeth. You notice its value not when you’re actively doing it, but when you stop doing it.” This is how I’ve come to see my engagement with religion overall. When I drop everything—reading scriptures from across religions, thinking and writing about religion, meditating occasionally—I notice how important those activities are for helping me to reinforce a sense of meaning in life, even when I’m not conscious of it.

Religion, as I see it, is that which allows us to express the inexpressible. For centuries, theologians have been mastering the art of expressing the inexpressible through writing, painting, ritual, and even science and mathematics. For them, God is the inexpressible thing crying out for expression. But this theological craft, which can be learned by studying religion, can be applied to other areas of life as well. For me, the entire constellation of feelings, emotions, and thoughts swirling around in my mind while it was waging an irrational and unwinnable war with itself was inexpressible. For others, it might be the sudden death of a loved one that sparks such an experience. There are certain thoughts and feelings that simply do not allow us to rest until we can properly articulate them—that is, establish a healthier connection between the conscious and unconscious. Many people turn to psychology to help solve that problem, while others might turn to something like poetry. In my estimation, though, human beings have devised no discipline of study or mode of inquiry as devoted to articulating the full scope of what lies beyond our ordinary state of conscious awareness as theology.

I have still never had any profound spiritual experience. But I’m okay with that. I understand now the other important functions that religion serves in my life. I began studying religion with the intention of finding some way to rid myself of all that was weighing me down: depression, existential despair, and the morass of ennui resulting from a dissatisfaction with the mundane vicissitudes of earthly life. Ironically, though, the mundane is the primary source of meaning in my life today, a sense of meaning grounded in theological ideas from across different religions, but especially those of East Asia—mainly Daoism and Zen Buddhism, both of which stress the importance of things like silence, simplicity, and contentment. The ideal Zen spiritual journey is sometimes depicted as a circle: you eventually end up exactly where you began, but the you is now different. I never found that magic pair of rose-colored glasses, but I did scrape off a lot of the crud that had been collecting on my colorless glasses. Deep down, I do identify as religious. And it’s not like my circular journey made me more religious; it just made me rethink what religion is.

There is a massive wave of young people opting for identity labels that serve as rejections of religion, which, to them, is synonymous with belief in a Western anthropomorphic God, a denial of scientific facts, and a cultish devotion to corrupt institutions. But religion is so much more than that. And these labels bother me a bit. With their emphasis on negation—“nones,” “spiritual but not religious”—I worry they are subconsciously signaling to their adopters, “You are either religious or not. Once you check the ‘no’ box, you need not think about religion ever again. It holds no value for you.” And if I had let myself believe that, there’s a real possibility I would not be alive today. Because I really do think that the study of religion helped to save my life, doing just enough to silence the murmurings of suicidal ideation during my darkest days. I still see tremendous potential for the good things that religion can do in people’s lives and the world as a whole. My hope is that I can help other young people see that as well.

So, once more, do I believe in God? Maybe. I can believe in a God that may reveal itself in different ways to different people at different points in life. It’s possible that one of these modes of revelation might be silence: the silence that comforted me in between bouts of severe depression, the silence that disturbed me when my efforts to establish a religious connection seemingly failed, and the silence that enriches my life with meaning today. Aldous Huxley referred to silence as “that which comes nearest to expressing the inexpressible.” The Daoist sage Lao Tzu very bluntly observed, “Those who know don’t talk; those who talk don’t know.” Jesus remained silent before his accusers on the way to the cross and the Buddha was known to sometimes answer his disciples’ questions with nothing but a silent smile. Silence can, in fact, be pregnant with theological meaning.

A professor of mine used to aptly refer to the great saints and mystics across religions as “the Michael Jordans of spirituality.” We tend to assume that such individuals were in constant communication with God. But when you read their autobiographical writings, you will find that this is rarely the case. The moments in which they had a direct experience of communing with God were few and fleeting. Even for them, God was silent most of the time. C.S. Lewis was an atheist until his thirties, when he had a revelatory experience that made him believe in God. This perspective made him empathetic to the fact that religiosity looks different for everybody: it can begin early in life or late in life; it can proceed gradually or in sudden bursts; it can be loud, quiet, or even silent. And when it comes to religious concepts that may feel foreign or ungraspable in the present, Lewis had some compassionate advice: “Do not worry. Leave it alone. There will come a day, perhaps years later, when you suddenly see what it meant. If one could understand it now, it would only do one harm.”

For now, I will choose to believe that there is something more, and I may find out about it one day when I’m ready. I’ll go on thinking and writing about the aspects of religion and theology that do mean something to me, while listening in silence to those that don’t.

And I’ll keep brushing my teeth.

Allen Simon is a Boston-based freelance writer with an MTS from Harvard Divinity School and a BA in Religion from Rice University.

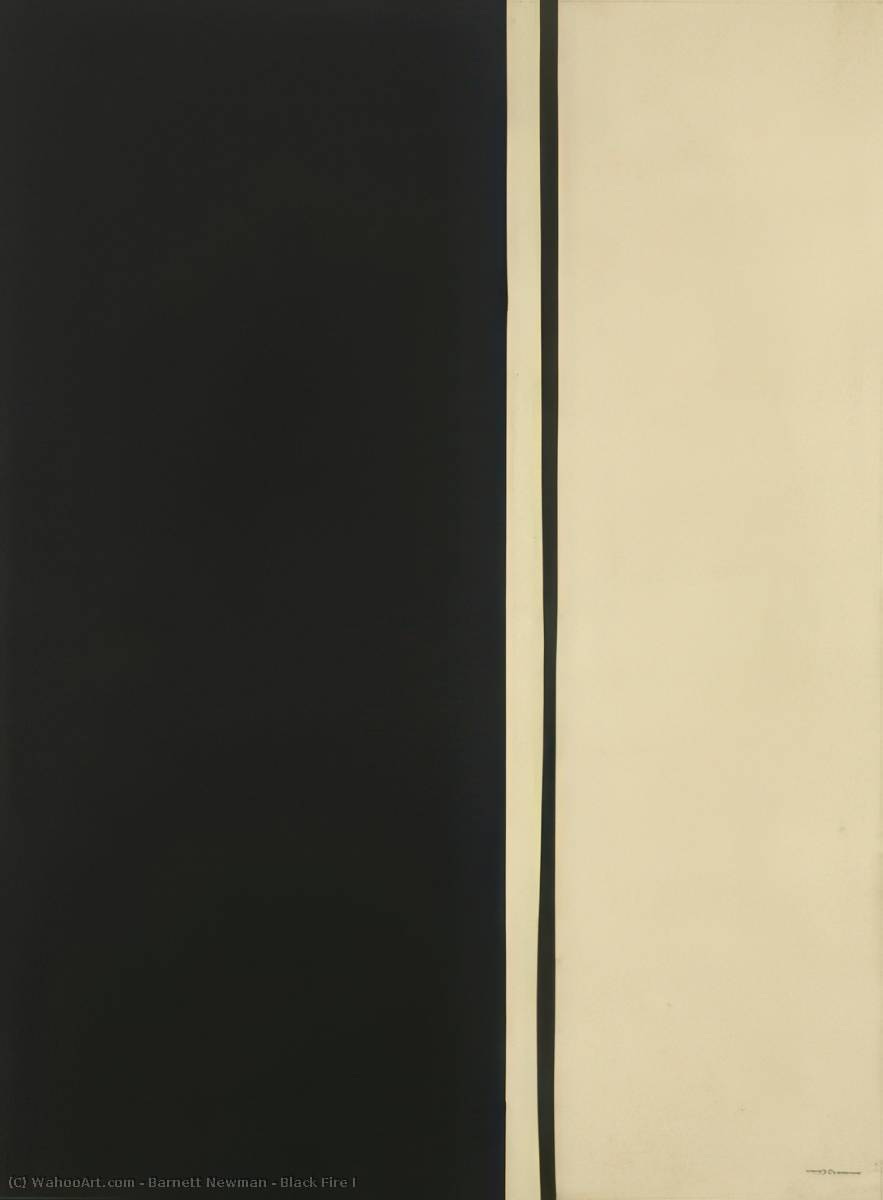

Art by Barnett Newman

This is among the best things I’ve read in Wayfare, and I'm so happy to see it published here. I resonate deeply with all of it. Thank you for writing.