Note: Our hope is that this reading can be deeply devotional. To be so, however, will require some moments of quiet and place and space where you can listen to the music (included below) and read along. We hope you’ll find some time, perhaps under the soft glow of lights in the last hours of evening, to enjoy.

One of the most transcendent Christmas settings I have encountered in modern music is Ola Gjeilo’s O Magnum Mysterium. From careful and repeated listening, I have learned a great deal about why Christmas Eve could matter even more than Christmas.

The five-minute choral piece deeply explores a simple lyric drawn from a traditional sacred text:

O Great Mystery, and wonderful sacrament,

That animals should see the new-born Lord, lying in a manger.

Blessed in the virgin whose womb was worthy to bear Christ, the Lord.

Alleluia!

The lyric itself—sung in Latin, an unadorned song of praise to Mary and her son, an exclamation of wonder at the miracle of Jesus’ birth—has been set to music many times, featured as a plainchant as far back as the middle ages, with formal choral settings starting in at least the 1500s. The origin of the text itself remains obscure.

Using the Youtube recording by British choral group Tenebrae included here, let’s work our way through the piece. For easiest listening, we recommend opening the Youtube video in a separate window so you can stop and start without scrolling up and down in this window, or switching tabs away from the essay.

We’ll use the timestamps from the Tenebrae recording as our wayposts. An indication of when to start the recording follows below. We recommend pausing at each timestamp to read, process, and then play the indicated section through to the next pause point. That way, you can be thinking of each block of text as you listen to the corresponding section of music.

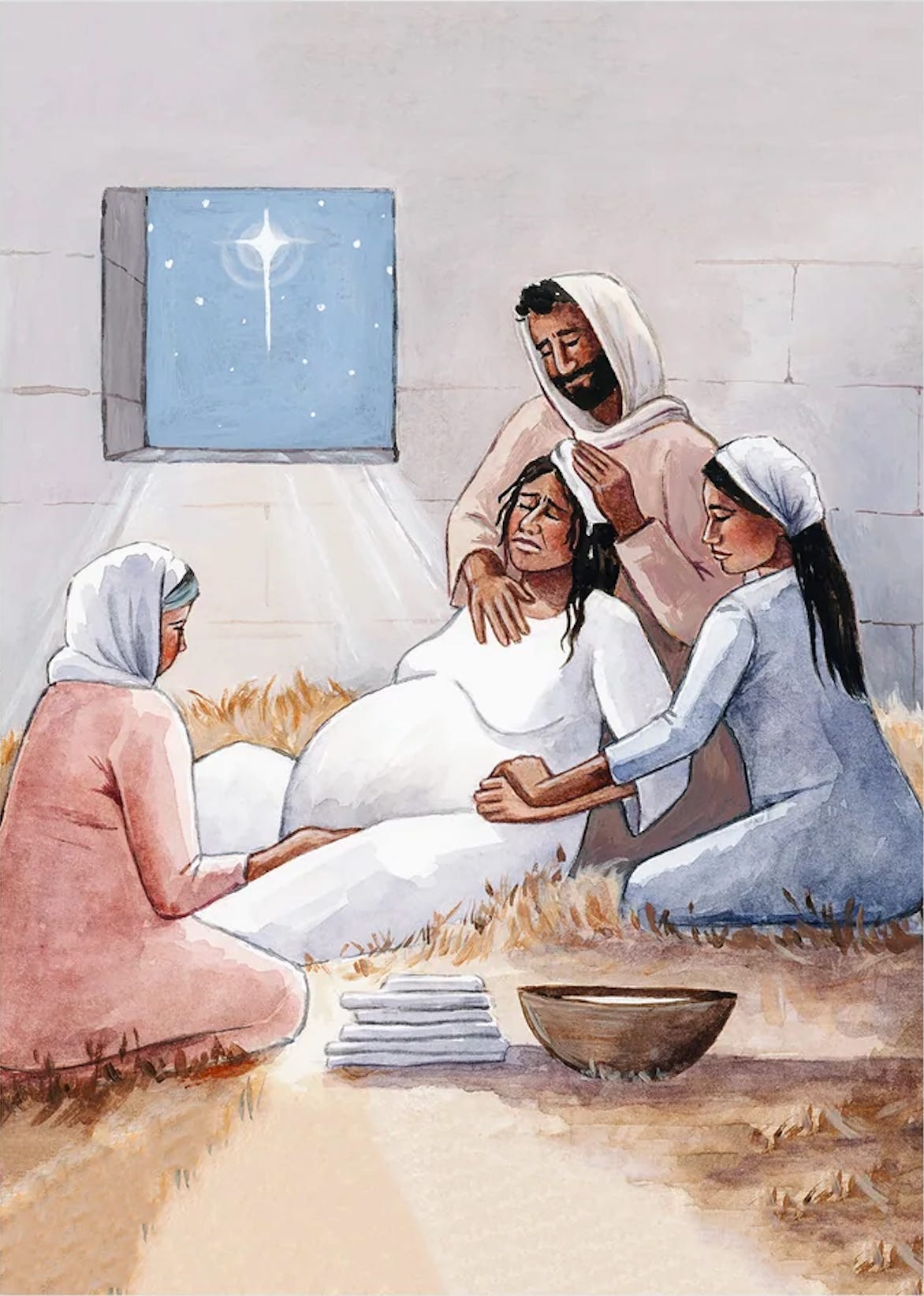

Imagine, as we begin, a weary Mary and Joseph, now finally resting in an animal stall, a midwife likely beside them. Mary’s contractions have been strengthening, growing closer together. The midwife knows delivery is near. Joseph is asked to wait outside. Mary’s laboring in earnest begins. Let’s imagine we find ourselves in the hours before dawn.

[Press play on the Youtube recording]

0:00—The entire choir enters with hushed intensity, on a chord that suggests weariness, tenuousness, trepidation, struggle, and even fear.

0:25—A cello enters, almost inaudible at first. The cello’s first three notes constitute a lament, a groan, a cry for help. Mary’s contractions deepen. An enveloping pain tautens every muscle—from those in her forehead to those at her toes—together. The fourth and fifth notes suggest a temporary surrender—this contraction subsides. As the cello obligato continues, we can hear an insistent goodness pushing back against an encroaching pain, an obstinate light worn weary against the shrouding darkness.

1:22—The light begins to grow, but remains tremulous, fragile.

Mary's tired body continues to prepare for the coming forth of a new life. Surrounded by pressure and unfamiliar aching, the passage to Mary's womb begins to change, the opening slowly stretching and thinning until it is finally wider than her own fist, clenched hard against the pain that rolls over her in waves.

The long hours pass, and the waves begin to come faster, with greater intensity.

The midwife meets each surging contraction with olive oil and pressure, massaging the taut muscles of Mary’s back. The pelvic bones rearrange themselves in preparation for the baby’s delivery from the shelter of the womb to the cold of the waiting world. We sense hope dawning just beyond the horizon, as if the first intimations of purple have begun to paint the waning darkness of the night. Still, though, the mood remains pervasively melancholy, and we sense a persistent anxiety suffusing the intimations of dawn.

1:47—The cello leans into a high “E” and we answer the overpowering tension by gripping it more tightly. The baby is crowning, Mary gasps into the night, her skin tearing, blood spilling onto the hay around her. Soon, the intensity of the pain recedes, like the tide pulling away from the newly wet sand, but that insistent bittersweet sensation lingers.

2:08—A full pause in all parts. The mood is about to transform.

2:10—Immediately, hope begins to grow. The sun has peeked above the horizon. Light waxes, expands, and sunbeams paint a sky that begins to glow. The tonal colors shimmer, an almost unbearable tension grips the air, we hunger for resolution and release until:

3:00—The newborn baby’s first exultant cry into the brightening world. The King of Kings is born. Mary breathes. Her muscles, strained to exhaustion, relax into blessed rest. The bleeding ebbs. The placenta comes. Mary reaches for her freshly cleaned baby and lays his warm weight against her bare breast. He is here, and he is real. Together Mother and Child are wrapped in linens. The shepherds and animals look on in wonder. Joseph, overcome, sinks onto the ground.

3:30—But as soon as the moment of transcendent resolution arrives, it has vanished. A breath. A pause. Again, melancholy chords perfuse the air. The cello laments. The baby, no longer a passive bucolic presence, begins to wail into the night. An empty infant stomach will need filling. The afterbirth must be attended to. Reality immediately begins to encroach on the idyllic scene.

4:22—The piece begins its coda. The parts shrink toward pianissimo again, the choir will take another 46 seconds to fully arrive at silence. The shepherds depart. The animals return to their feed. The birth has ended. Mary begins to feed the child at her breast. A weary world returns to its passing concerns.

So, what does all this teach us about why Christmas Eve matters?

I wonder if we churchgoers sometimes rob scripture of the very power it has to sustain us by skipping to the resolution, the safe and happy birth, and the supposed point of final rest. But Gjeilo’s setting reminds us that the notes of exultation don’t even arrive until 3 minutes into a song that lasts less than five. And when that transcendent chord finally arrives, it derives its entire meaning from the labor, melancholy, and dissonance that came before. What’s more, it lasts for only two measures—eight counts—before it immediately begins degrading, transforming, and falling back toward a more complicated and melancholy rest.

To hear Christmas sung in carols and to see it depicted in art, one would imagine that Mary and Joseph were transported, gleaming and dewy-skinned, to an immaculate stable without a dab of dirt or a hint of sweat. And that the baby was delivered, already wrapped in glistening linens, smiling and cooing–”no cry did he make.”

Is this the religious version of a photoshopped Instagram post?

When we absorb these idealized versions of the nativity, do we feel that our lives should likewise be as tidy and glowing as that depiction of the holy family gathered around the manger?

Certainly we ought not to. To depict the birth of God’s Son as sanitized and easy is untrue in the deepest sense—Jesus was not born to live a sanitized and easy life—and also untrue in the sense that, historically, birth was anything but. Jesus’ birth was no exception. That ride on a donkey—with a near-term mother-to-be over dusty primitive roads—must have been grimy, sweaty, dirty, and abominably uncomfortable. Indeed, how does one even fit a nine-month ripe uterus and fully-formed child—plus all the rest of her body—atop a donkey? Likewise, the stable likely smelled of dung and was uncomfortable in the extreme. There was, of course, no anesthetic to take away the pain, and Mary birthed Jesus in an era when infant mortality likely hovered around 50%. Maternal mortality was also high, meaning that the very prospect of bringing a baby into the world was, by definition, an experience freighted with existential angst. And, finally, birth itself is an event which, in any day and any age, can only be fully understood by those who have groaned, grunted, wept, and endured their way through it.

The rest of us can only look on in admiration and wonder.

But all of this is why Gjeilo’s setting matters so much. Like the journey of Joseph and Mary, and most especially like Mary's labor, life includes precious moments of transcendence, beauty, harmony and resolution, yes, but also, and often more persistently, entire pages of dissonance, difficulty, and pain. When Lehi teaches his sons that there “must needs be an opposition in all things,” he seems to be testifying to the state of the universe, simply acknowledging what most people learn by hard experience—that life, for many of us and much of the time, remains deeply hard.

I imagine we turn to the bucolic version of Jesus’ birth for the same reason we sometimes shy away from recounting the horror of Christ’s crucifixion in favor of focusing only on images of the resurrected Lord—because in our moments of deepest need we long to know that, as Elder Holland once promised, “for the faithful, things will turn out right in the end.” When we are in the dark, we want to believe in Light. When we doubt, we yearn for Truth. When we are lost, we search for a Way.

But if we define our happy ending as unsullied perfection, we can feel both robbed and guilty when our lives do not look beautiful printed on a Christmas card. We may ask: “Have we done something (or many somethings) to miss our chance at happiness?” Or “Has God left his promises unfulfilled by not delivering us as we hoped?”

But, in fact, a transcendent truth is woven into the warp and woof of our theology: opposition, pain, and even suffering are components of the universe as eternal, immutable, and indestructible as the elements that descended from the stars into the tissues that are our bodies. Our Heavenly Parents—whose image we bear and whose nature we strive to emulate—live a life suffused with suffering, having filled the seven oceans with their tears.

If we believe we will one day arrive at a place unmarred by the vicissitudes we currently experience, then we are journeying in the desert toward a mirage. There is no destination free from opposition. We must let go of such an idea as inconsistent with God. As Mary could not bear her child without pain, so we cannot encounter God without experiencing opposition. None of this is to deny the reality and forceful beauty of that moment when Mary cooed a lullaby to a blissful, sleeping baby—I very much hope just such a idyllic moment happened in just that way—but, rather, to recognize that I encounter the full weight and power of scripture when I recognize that the lullaby moments exists alongside the moments of labor, crowning, and delivery. It is in the pairing of the transcendent with the painful that I find the fullest truth.

Jesus did not come into the world to rid it of suffering. After all, the night of his birth would have brought to Mary torn skin, the delivery of the placenta, the pain of a difficult latch, weeks of engorgement, and all the rest. Jesus came not to end suffering but, rather, to answer suffering with love.

This is my testimony of Christmas Eve: faith in Jesus will not make life easy, but when I commit whole-heartedly, faith will teach me to face the world’s suffering with candor and grace. When I am weary and saddened, then I am gifted the love only Jesus can give.

This is my prayer on Christmas Eve: may I submit to the labor of this life as Mary submitted to the labor of her delivery, and in so doing, may God bring forth within me the miraculous work of love.

Thus, as we take a moment this night, before the riotous joy of wrapping paper and festive foods that will come tomorrow, let us savor the silence and the glow of lights on a Christmas Tree. Let us listen to O Magnum one more time. Let us imagine the laboring, exhausted, sweating, tearful Mary and let us remember that the meaning of Jesus’ birth is not that He takes from us our suffering, but that He teaches us how to live and love as we suffer. Jesus creates within and among us an affection that brings peace in suffering, and meaning in sorrow.

From all of us at Wayfare, Merry Christmas Eve.

Rachel Jardine is an Associate Editor at Wayfare. She mothers her children in San Antonio, Texas, and practices law.

Tyler Johnson is a Wayfare contributing editor and an oncologist and Clinical Assistant Professor at Stanford University.

Artwork by Paige Payne, Gari Melchers, and Alice Abrams.

Thank you for providing this sacred moment. It was absolutely beautiful. It was so instructive too, as I am wrestling and wrestling and wrestling with opposition having a place in the Divine experience. My life is a daily torture of opposition and has been to an intense degree for over a decade. But your words ring true to me: "It is in the pairing of the transcendent with the painful that I find the fullest truth." It is in my darkest night, when in the pains of the labor I am called to suffer I find Jesus. Waiting for me there.

"And He walks with me, and He talks with me,

And He tells me I am His own,

And the joy we share as we tarry there,

None other has ever known."

i'm hesitant to break this beautiful spirit by even writing anything. But, The spirit continues to move… I am often inspired by contemplating all the many cultural elements to the context of Mary and Joseph's ordeal. but, I confess I had not thought about the embodiment of love and courage and endurance in this way. Yes, I have taught about the physiology of childbirth in my classes, but to overlay that with the birth of our savior is glorious. At once, Mary was saving Him and He was saving her. perhaps it is that way for all parents and children as they make their way through the blood and bones of this mortal life. Having never experienced childbirth, tonight, I bend the knee to all of you who have and a big thank you to our authors for taking the time to make such sacred space for the rest of us.