Becoming God's Family

Lessons From My Iraqi Brother

The summer of my junior year in high school, my parents attended a meeting about a student exchange program. It was a short program, two or three weeks. Each family would host two Iraqi high school students. They would come from all over Iraq: Baghdad, Basra, Kurdistan.

In preparation, we had a few meetings with a man who had lived in the Middle East and spoke Arabic. He taught us things like providing a pitcher of water or, minimally, some wet wipes in our bathrooms so that the students could perform Wudu. He taught us about the prayers and prayer times. We learned that there are five prayers but many Muslims do them as three events. And it is an event. While a Mormon prayer tends to be something of a momentary cloistering, a Muslim prayer is much more of a production. The rug, the standings, bowing, kneeling, standing, arms up and down, not to mention the recitations. Like all people, Muslims are governed by practicality and propriety, but the prayers seem set up to be impractical and inconvenient. To pray is itself a sacrifice. I grew increasingly excited to witness this foreign culture and religion, not on a TV screen but in my own home, sharing my very bedroom.

Ali was the boy assigned to stay with us. He was slim, athletic, and came with all the fixtures of a deeply religious upbringing. But while we played soccer together, attended classes together, ate meals together, and shared a bunk bed, I never witnessed him pray. He never unfurled his rug, or knelt or chanted or anything. And it wasn’t just Ali. Several of the girls who were staying with other families had taken off their hijabs. It was strange. We had expected and prepared for an encounter with Islam. But it was as if the old and beautiful religion could simply be taken off. As a religious boy myself, there was something threatening in this reality. And I began to resent Ali for abandoning his faith so quickly.

On Sunday, Ali insisted on going to church with us. The first day he attended was fast Sunday, and without any prompting or explanation, Ali figured out what was happening and decided to take a turn. I was shocked to see him walking up to the mic, something I had only done a few times in my entire life. And he stood there a long time, speaking about his life back in Basra. It was remarkably brave or ignorant or something else altogether for him to stand there in the attitude of a Mormon submission. But I felt none of the excitement I’d experienced when an investigator spoke for the first time—another step towards baptism. Instead, I felt deeply and passionately that Ali should remain Muslim. In later conversations with my mother, I learned she felt the same. So we were glad when it was time for Ali to return home to his family, his country, and his religion.

But when the time came, he ran away. Imagine that: a sixteen-year-old boy fleeing all by himself into our country. A year later, he returned to us, and we were able to help him receive political asylum, graduate high school, and attend college. We sustained him with Mormonism and eventually helped him return to Islam. It was a strange thing to use our faith as a splint for another. But soon, we were practicing the principles of Islam and Mormonism together under the same roof.

This was a disquieting experience for me. I believed in my faith and planned to serve a mission to convert others. My oldest brother had just gotten home from his mission and my second oldest brother was serving his. And here I was actively, intentionally, nurturing a Muslim boy back towards his native Islam.

In an attempt to deal with my own certainties and ambivalences, I started writing a book about Ali’s experiences in America. But I soon realized that I was using Ali’s story to write my own. And while that probably sounds pretty egocentric, I’ve come to believe it’s unavoidable. And what’s more, I don’t think it’s entirely regrettable. There is something beautiful about the fact that we lean into each other. That our stories and agencies are all intertwined. And when we move, it is not through empty space, but through one another.

In a real way, I believe this sort of interfaith inter-connection is simply the state of affairs. We borrow from across the aisle, we bolster, commune and share identity even from unknown and disparate places. President Nelson has recently made the Christus by Bertel Thorvaldsen, a Lutheran artist, the icon of our church. Our hymn book borrows heavily from the Wesley brothers, the founders of the Methodist faith. Our fast and testimony meetings feel distinctly Quaker.

But our borrowing is deeper than close Christian relatives. The tune for Praise the Man, which has filled many a youthful heart with conviction of Joseph Smith’s prophethood, is borrowed from a folk tradition and is filled with Scottish nationalism. Much has been made of the similarities between our temple ceremonies and Masonic rituals. It’s not hard to see Greco-Roman influences in the Bible itself. Thomas Aquinas, whose philosophies permeate all of Christianity, borrowed heavily from Muslim scholars Ibn Rushd and Ibn Sina. Everything from the paganism of Christmas to the medievalism of Easter, it is all, already, deeply connected, interfaith, interdependent.

There are various responses to this reality. Ignorance, acceptance, avoidance, or excision. But excision is more of an attitude than reality. We could try to take all the paganism out of Christmas, but we would fail. And if we succeeded, we might be surprised to find that Christmas lost some of its magic. Somehow, the Pagan parts sanctified more than tarnished.

Acceptance is also not without its dangerous implications. There is an unspoken threat to transference, even in conversion. The transfer of a member from one faith to another is never one-sided, never without baggage, germs, and hitchhikers. Whenever we have a convert, the church is also converted. Each convert comes with their own gravity and that moves the church a little. Imagine what would happen if we converted the whole world of Islam. We might not even know it but we could become Islam like Christianity became Rome.

Writing a novel was an attempt to figure something out about this interwoven and inseparable reality. And what I learned was that interfaith is more than inter-toleration, inter-respect, or even inter-collaboration. Interfaith, in a real way, is like having a brother. And that was ultimately the task I had with Ali. It was not to make him Muslim or Mormon. The task was to make him my brother.

This realization came at the end of my book. I describe walking onto a soccer field with Ali:

When we arrive, Ali puts his arm around me and I put my arm around him, throw the soccer ball in front of us and we walk onto the field together. And for the first time he feels like an actual brother, like I wasn’t pretending.

Interfaith work, in an important way, is simply to stop pretending, and admit the interconnected state of affairs. And this coming together is less often like the conversions we hear at testimony meetings and much more like sharing a room with a brother. There will be disagreements and differences, even genetic differences, but also an inseparable, undeniable connection. So much of being a brother is getting past pride and jealousy so we can be a pillar when the world is crumbling, to share meals and conversations after a hard day, to have a place to spend holidays. Interfaith work, ultimately, is the work of bringing God’s family together as the family we actually are.

Joshua Sabey is the author of Ali and an award-winning director, producer, and writer. His work has been featured in multiple major news sources including The Christian Science Monitor, The Fulcrum, WBUR, and more.

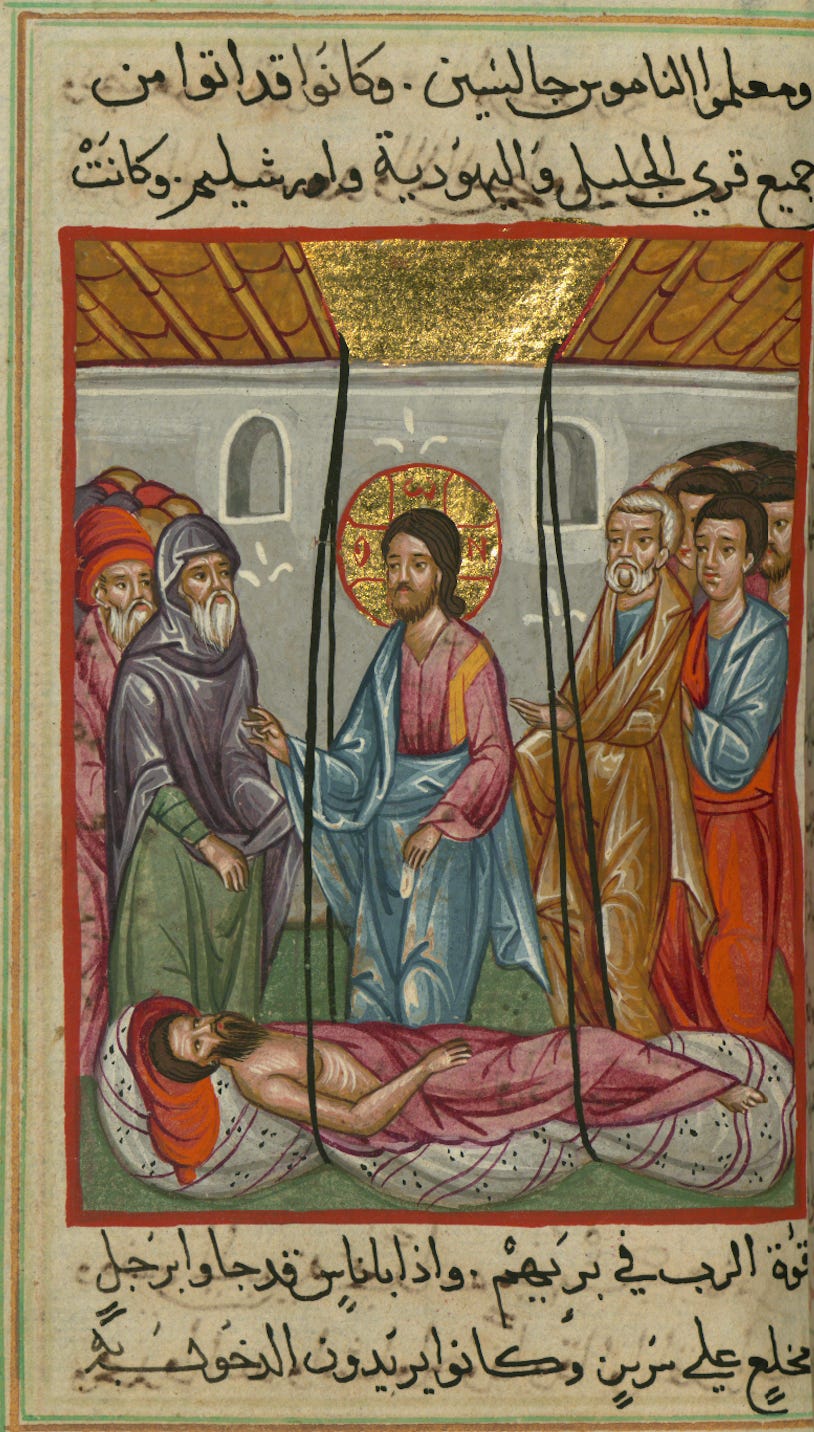

Artwork from an illuminated Arabic manuscript of the Gospels by Ilyās Bāsim Khūrī Bazzī Rāhib (الياس باسم خوري بزي راهب), a Coptic monk. To view more of the artwork from the manuscript, click here.

Love this article! Thank you!

I wholeheartedly believe in PRISCA THEOLOGIA— and in the First Presidency’s 1978 statement acknowledging Muhammed, among others, as “great religious leaders”. I also wholeheartedly believe that temple work for all of God’s children is proof that He is is serious about wanting us all back home. Not as coloring book images with all the lines filled in perfectly, but as glorious works of art.