In 1903, Bertrand Russell set the tone for the eloquent atheism of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. A century before the rise of the “new atheists” (Richard Dawkins and the like), Russell argued that only knowledge derived from science can form the foundation of meaning. Russell knew dismantling religion would yield despair, but believed that despair was a necessary foundation for any cogent thought or philosophy. He wrote this as part of one of his most moving essays:

Such, in outline, but even more purposeless, more void of meaning, is the world which Science presents for our belief. . . . That Man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, . . . are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man's achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins.

In many ways, the twentieth century seems—at first glance—to have shown Russell to be something of a secular prophet. After all, the ascent of science and its great accomplishments are unquestioned: we split the atom, harnessed quantum mechanics, made an artificial heart, reprogrammed immune cells to fight cancer, and peered into infinitely distant galaxies to see the spectacular reach of the cosmos. It can hardly surprise us that science sometimes seems to have made religion obsolete.

At the same time, even as science has ascended, we also find a world increasingly riven by despair. One would think that the advances outlined above—and countless others, besides—might have made the world, if not largely happy, at least significantly happier than before. Instead, the overriding sentiment as we look back on the twentieth century from our twenty-first century post is one of weary resignation, jaded cynicism, and sometimes, just as Russell predicted, even despair. That latter emotion comes most prominently as we remember instances where we must look, without escape, on the scope of man’s inhumanity to man. Perhaps the Holocaust stands as the century’s most harrowing example. Elie Wiesel wrote of his experience:

Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, that turned my life into one long night seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the small faces of the children whose bodies I saw transformed into smoke under a silent sky. Never shall I forget those flames that consumed my faith for ever. Never shall I forget the nocturnal silence that deprived me for all eternity of the desire to live. Never shall I forget those moments that murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to ashes. Never shall I forget those things, even were I condemned to live as long as God himself. Never.

And our collective consciousness never has.

Indeed we risk empathy fatigue as we recall the ruin of other major wars, genocides, famines, and human-aided disasters. Much in our dark history of just the twentieth century follows the open abuses of science I am calling scientism, or when science becomes a blind and unscrupulous servant to power. Nearly a quarter of the way into the twenty-first century, scientism has bequeathed us a world that is prosperous, but meaningless; connected, but lonely; rich, but spiritually empty.

It is perhaps only this far into the era of ascendant irrelgious that we can begin to grasp just how achingly we need transcendance and communion. I am struck that one of modernity’s most urgent lessons may be this: that religion, for all its serious problems, answers pressing societal questions—not to mention the longing of the soul—in ways we will have great difficulty replacing if religion recedes as an organizing force in the “developed” world. Increasingly, we may turn together to God not because doing so is nice but because we now see that, without God, the world begins to come apart in fundamental, even definitional, ways. As just one example, it is hardly an accident that the retreat of church communities and the rise of the Russellian hopelessness have occurred hand-in-hand with a startling rise of “deaths of despair” and what the U.S. Surgeon General has called an “epidemic of loneliness.” Our abandonment of religiosity has occurred simultaneously with a rising tide of depression and meaninglessness. I cannot help but wonder if this doesn’t stand at the root of some of the twenty-first century’s most vexing societal, psychological, and civic problems.

My purpose in this essay is to suggest that religion in general—and restored Christianity in particular—matter so much, in part, because they propose fundamental insights that mend what the postmodern world is rending asunder. Where postmodernity robs the world of meaning and leaves us increasingly empty and atomized, the restored gospel offers a wealth of ideas—and a way of life—that return to us purpose and community. The effects of these insights and lifeways are hard to measure, but they strike me as offering a meaningful frame for engaging both the beauty and the suffering that surrounds us.

Let’s consider these twin forces (beauty and suffering) in turn.

The first is simply this: every level of the universe—from the behavior of subatomic particles in the quantum realm to the arcing of galaxies across the darkened canvas of space—bespeaks God’s embodied love. King Benjamin evokes the idea this way:

[God] is preserving you from day to day . . . lending you breath, that you may live and move and do according to your will, and even supporting you from one moment to another. (Mosiah 2:21)

In more modern parlance, Adam Miller has articulated a similar idea:

The original grace of creation—the very same original grace that welled up on the first day of creation—is the same creative grace that continues surging upward even now. Here, the present moment is ground zero for God’s grace: it is the world continually being created and recreated, continually arising and passing, continually spinning and changing, continually given and taken and given again.

The Christian life invites us to see the warp and woof woven into our existence—and to recognize with shock that the tapestry was woven because of love. Indeed, from my perspective as a doctor, the more science reveals about the workings of the universe, the more God’s love is revealed.

As just one example: every person you see walking down the street started as a single cell. This recognition, when I consider it even for a moment, stops me in my tracks. It simply astounds. A father’s sperm penetrates a mother’s egg and the DNA from the two cells fuses. At that first moment after fusion, three things are true about the resulting organism: (1) it is (save the presence of an identical twin) unique in all the world; (2) it contains within itself all the information needed to construct an entire adult human; and (3) if allowed to fully develop, that insensate collection of chromosomes and mitochondria will become capable of the crowning and ineluctably mysterious human capacity: consciousness.

I have difficulty conveying the absurd precision, the dizzying beauty involved in this developmental process. First, that single cell must divide endlessly until it becomes one hundred trillion copies. But it’s not just that—because, eventually, the copies are not copies at all. As an embryo unfurls, it must direct this cell to become a heart cell, while this cell becomes a liver cell, while this cell forms part of the retina. And then each of these cells must know where to go and how, if at all, to connect to cells surrounding them. And the majority of this process happens before the person is even born.

This is akin to a trapeze artist, on a rope suspended between two skyscrapers, balancing six buckets of water, doing flips, while spilling nary a drop.

It. Simply. Staggers.

That the process ever came off successfully, even once, in the history of humanity boggles the mind. That it happens with great fidelity every time a human is born—that it is the unvarying prerequisite for the very existence of every human—leaves this doctor slack-jawed. But it is also more than just astonishment, as vital as astonishment is and as much as wonder may succor. Beyond astonishment, the process of learning to see the world’s beauty as the work of Divine Parents leaves us with endless reminders not just that the world is improbable but that the world’s beauty—and our wonder at beholding it—reflects forever parental love. Thus, every encounter with foundational love does not simply dazzle us, but leaves us, instead, full of a sense that we matter and are loved.

And that is the thing about this sense of divine re-enchantment: once I see it, it abounds everywhere, in everything. It is the force that refracts colors into a rainbow, the passage of oxygen from air into the blood in the lung, the unique sparkling beauty of a snowflake, the soundwaves that carry Lauridsen’s “O Magnum Mysterium” to my ears, and the shimmering and evanescent beauty of fall foliage against a darkening sky.

The enchantment of the universe can very quickly overwhelm us, leaving us bursting with a sense of our own blessedness, merit, and infinite belonging. But, of course, Russell did not turn away from a God of rainbows and fall-colored trees. Were the universe made only of beauty, then believing in God would become much easier than it is.

For religion to mean anything, it must do more than simply affirm the meaning of what we already love. To matter, religion must also say something about suffering—why is it here? What does it mean? And how are we meant to respond when it intrudes? The project of any religion that purports to speak meaning into the universe must be to answer this question: what are we to make of a world that offers both inexplicable beauty suggesting God’s ever-present love, yet also ever-present suffering that seems irreconcilable with that same affection?

As an oncologist, I watch and witness as my cancer patients confront suffering all the time. Indeed, that cancer is a byproduct of the processes that create our own DNA will forever remain biology’s fundamental paradox. Perhaps as an occupational hazard, then, I think of what the presence and ubiquity of suffering means for a believer.

And in this regard, I find The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ answers compelling—and hard. From our reconceptualization of Eden and Eve’s choice to our understanding of what salvation means, I believe our theology offers substance to the suffering that deserves more attention than we often give.

And no scriptural account captures these insights with such stunning power as Enoch’s vision in Moses, chapter 7. For our purposes, I want to focus not so much on what the chapter teaches us about God, but instead on what it teaches us about what being with God does to Enoch.

Enoch is flummoxed to see God crying, pleading over and over to know “how is it the heavens can weep?” But what is key for us to see is this: it is not just God who turns to the world with compassion. Enoch, too, becomes keenly aware of—and responds with native compassion to—the world’s suffering.

And it came to pass that the Lord spake unto Enoch, and told Enoch all the doings of the children of men; wherefore Enoch knew, and looked upon their wickedness, and their misery, and wept and stretched forth his arms, and his heart swelled wide as eternity; and his bowels yearned, and all eternity shook. (Moses 7:41, emphasis added)

This brings us up against a powerful paradox. It would be easy enough to say “I believe in God because of the beauty I find in the world.” But that’s not the only thing our religion offers us. Restored Christianity fixes our eyes on beauty, yes, but also on suffering and, by doing so, invites us into covenantal empathy with God that extends in ever-widening circles, encompassing more and more of our fellow travelers, until we are brought to a love as consuming and infinite as the reach of space.

Indeed, the word “empathy” itself—remarkably—never occurs in the scriptures. Yet, I would argue it is woven like a golden thread through our understanding of God’s nature, and of the life God invites us to live in communion with the divine. Indeed, I am struck that empathy underlies and powers a great deal of what constitutes a covenant life for a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Our covenants make clear that God cares about our willingness to bind ourselves to the suffering of those around us. Empathy lies, after all, at the heart of Alma’s formulation of our baptismal covenant. Likewise, what could more viscerally evoke our empathy than the weekly tokens we take to remember Jesus’s suffering?

In the same vein, Doctrine and Covenants Section 121—whose second half articulates the prerequisites for exercising authority in the priesthood—invites us to a world where power derives its force from empathy.

And, finally, our temple covenants culminate with the promise to consecrate all we have and are to the healing of a wounded world. Building the Kingdom of God and establishing Zion requires us to see what Enoch saw, to be shaken as he was shaken, and to wear out our lives in relieving suffering and want until there are no poor among us. We are to prepare the world for the arrival of the Prince of Peace by mending what was broken and by speaking peace to a people too often at war. Indeed, one way of framing the place of empathy in the godly life is to observe that our covenants invite us to develop compassion as the implicit way we come to see the world—and especially those who suffer in it—so that we will be moved by divine love to act compassionately as the explicit manifestation of how God’s love moves us to exist in the world.

As our Christian conversion deepens, we are brought first to an enchanted comprehension of the miracle of our own creation, but then, just as quickly, we peel our eyes, as it were, away from the telescope and the microscope and turn our gaze to what Nephi referred to as the world’s “awful woundedness.”

In this vein, it really is as Melissa Inouye once wrote:

Suffering never feels right. It feels like suffering. Like prayer, it is a form of work. . . . Having experienced suffering, one develops power over it—not power to stop it, or take it away from someone you love, but to know its sorrows fade. Having experienced suffering, one receives power from it—the power to share others’ burdens and be humble, to see one’s own burdens and be kind.

Thus, on the one hand, the evidence the world provides of God’s love never stops abounding: the richness of soil, the sparkle of winter air, the shimmering of snow, the miracle of music, the reality of love, the poignance of loss, the structure of hemoglobin, the bond between lovers, the laughter of children, the function of words, the dazzle of light, the wheeling of constellations, the roar of waterfalls, and the sound of the wind.

But so, too, does evidence of suffering never cease: children starving, war rending, racism degrading, inequality binding, materialism grinding—the forgotten elderly, the confused teen, the ostracized lesbian, the doubting young adult, the displaced, the hated, the poor.

In one sense, the gospel’s approach to this paradox lies precisely in showing us that while these two forces—beauty and suffering—might seem to lie at opposite poles, they are nevertheless bound together in this fundamental unity: both draw us out of ourselves. In an age much too often defined by narcissism, where our attention is often devoted almost entirely to ourselves, both a recognition of the love behind beauty and the covenantal decision to engage with suffering as an opportunity for deepening our empathy can draw us out of what G. K. Chesterton called the “tiny tawdry theater” of the self and into Chesterton’s “street full of splendid strangers.”

It is perhaps at this point that this essay’s application to my own cancer patients becomes most clear: to begin with, the fact that the two of us—doctor and patient—are there to converse at all testifies to the unfathomably unlikely miracle of our own existence; yet, at the same time, the existence of cancer cells as rogue versions of the very molecular processes that power the creation of life reminds us of the myriad ways in which the miracles of biology can devolve toward suffering and chaos.

Even seated there in front of one of my patients, then, the restored gospel offers no easy answers but suggests, nonetheless, that embodied covenantal empathy is the characteristic of divinity capacious enough to encircle both beauty and suffering. Empathy is essential precisely because, of all God’s virtues, it requires from us the last true measure of our devotion. The answer to suffering cannot come from God alone; it requires us, too, to pledge ourselves to sacrificial, beautiful, and embodied love.

SUBSCRIBE TO ON THE ROAD TO JERICHO

Receive Tyler’s column in your inbox by clicking here and selecting "On the Road to Jericho."

Tyler Johnson is an oncologist at Stanford. His writing has appeared in Dialogue, BYU Studies, The Salt Lake Tribune, Religion New Service, Wayfare, and the San Jose Mercury News.

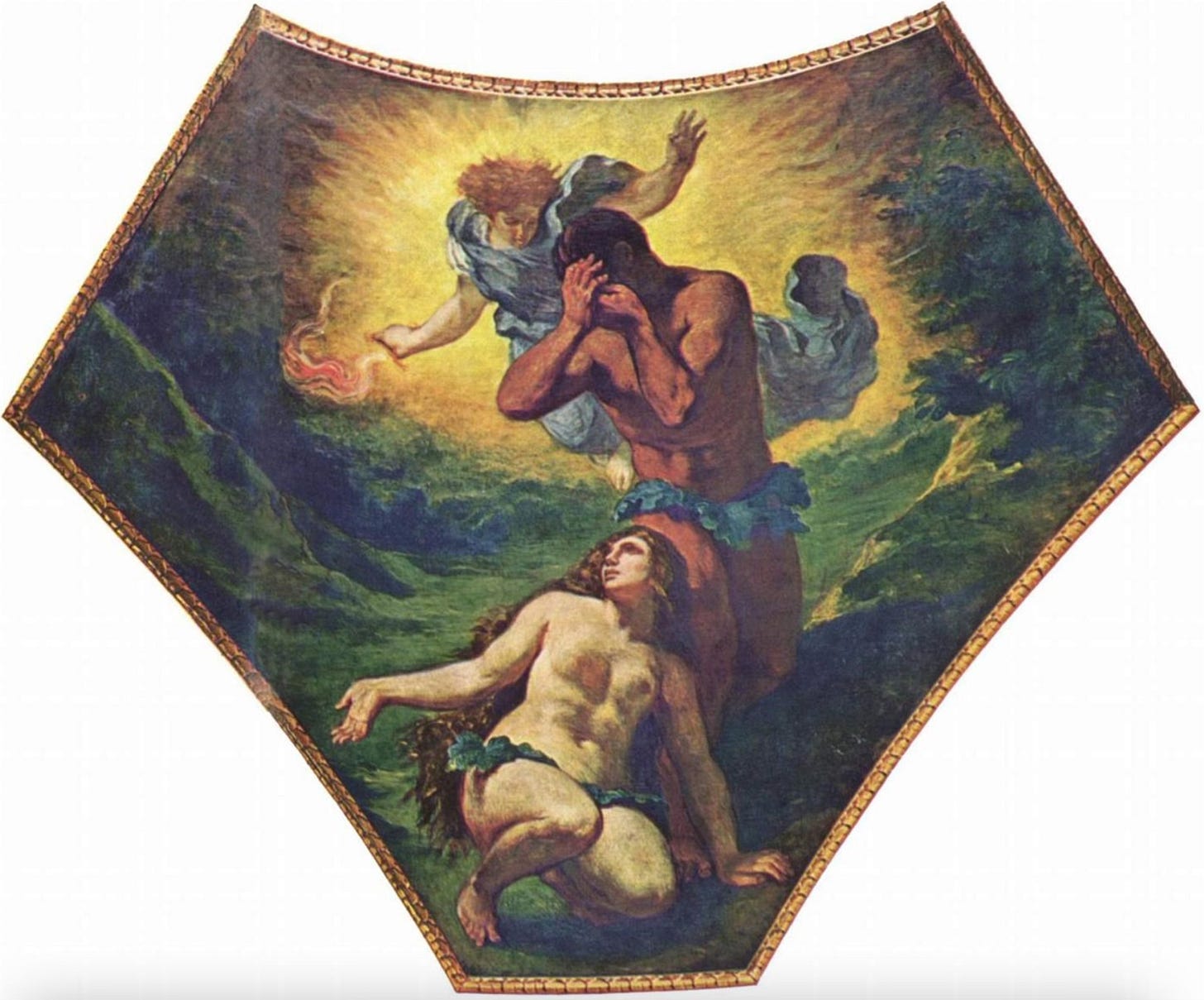

Art by Eugène Delacroix.