Back to Life

On a recent walk, my three-year-old daughter and I came across a dead opossum that had been killed by a car. My daughter was fascinated by the animal’s body and the drama of its demise. For days, the “opossum story” was told and retold. My daughter asked what had happened. She asked about death and whether all animals die. She asked if I will die. If she will die. So we checked out books from the library. We watched Charlotte’s Web.

As the concept of death has become more deeply entrenched in my little one’s worldview, I’ve noticed that her narrations about death often involve the dead “coming back,” usually echoing the language we have supplied her from the stories of Jesus’s miracles raising the dead or his own resurrection. Trained as a hospital chaplain, I have noticed my desire to jump in and correct her, to remind her that not all (not any) who die come back. I’ve stumbled over language about spirits and bodies and resurrection and heaven and living again. Getting curious about my struggles with the topic, I’ve noticed my feelings of resentment for these miracle stories which are so out of tune with the human ordinary.

Jesus comes back. He breathes again, and breathes life on his friends. The triumph of this assertion is perhaps reliant on its uniqueness; Jesus stands alone and apart, yet his very separateness bridges the chasms we feel between life and death. Still I find myself believing more in the cross, the tomb, and the grief of broken hopes in the story’s sequence. Maybe I find them more relatable, these very human aspects of the narrative filled with flesh and blood and hunger and pain. Maybe I struggle to find the same level of resonance with the return, the coming back, the reversing of finality.

Could we read the resurrection both as a story of deity and the story of humanity? I am used to a telling of this story that emphasizes overcoming, triumph, and victory over the morbid forces of life. But I wonder if this telling relies on paradigms that are not indigenous to the story. Easter Sunday does not erase Gethsemane, the cross, or the tomb. Easter Sunday, rather, emphasizes the constant return of life, and that this world is worth coming back to. Could renewal and return be, perhaps, the arc of the human Spirit, flowing indelibly with all of creation? Because death feels so very final, resurrection in turn feels distant. Especially for those who are bereaved, the cognitive belief in resurrection is almost never very comforting in the physical absence of a fleshy body. I look then not just to an abstract belief in a someday state, but to a story of renewal on a bright morning. To a reclaiming of what is human, even after the agony of a human existence. I look to a story of hope after hopelessness, and greeting after farewell. With such a lens, this may be the most human story of all: that life always perseveres, filling the vacuum of death. That the human Spirit is, above all, fiercely hungry for living, and that true death occurs only when that thirsty Spirit is finally quenched. Jesus’s life and teachings did not center on asceticism or denial of life. Rather, they emphasized awakening. Internal turning and nourishment, transformed hearts, invigorated spirits, loving bodies: these are the radical teachings of Jesus, and the resurrection does not diminish them. Instead, the resurrection may be the ultimate moment of embodiment and with-ness. Life is worth returning to.

Jesus comes back to a body. To pain and suffering. To fatigue, hunger, desire. The resurrection might be read not just as an overcoming of mortality, but as a choice to be in solidarity with it. To claim it, love it, and uphold it.

To be alive is chaotic. No one is guaranteed protection from the fates of randomness and entropy and chance. Trying to control the future, or to refuse to hope for it, are tokens of the same coin of resistance to willing submission. To submit to life is to accept instability, to give up the idea that things happen for a divinely appointed reason. Instead, we create reason. We dig in the gardens of our lives and cultivate meaning. We bring ourselves to life as we progress toward death. We resurrect as we refuse cynicism and despair. We feed the Spirit that flows through all things and, by so doing, we live.

There are both abundant paradoxes and abundant invitations to awe in this climax of the Jesus story. We return again and again, curious and wondering.

Full of life, my little one asks about death. I want to tell her the truth, and I want to shield her from the uncertainties I feel. And, with less anxious eyes, I see that the miraculous and the ordinary may not be such disparate things. Resurrection is all around us and constantly within us. The story of Jesus coming back is also the story of life bursting from ashes, and hope springing from long-closed hearts.

We are telling living stories, stories about ourselves and our world. We keep them alive in our bodies, tending to the cares of the day. It is enough.

Kristen Blair works with practical theology and lives in Toronto, Ontario.

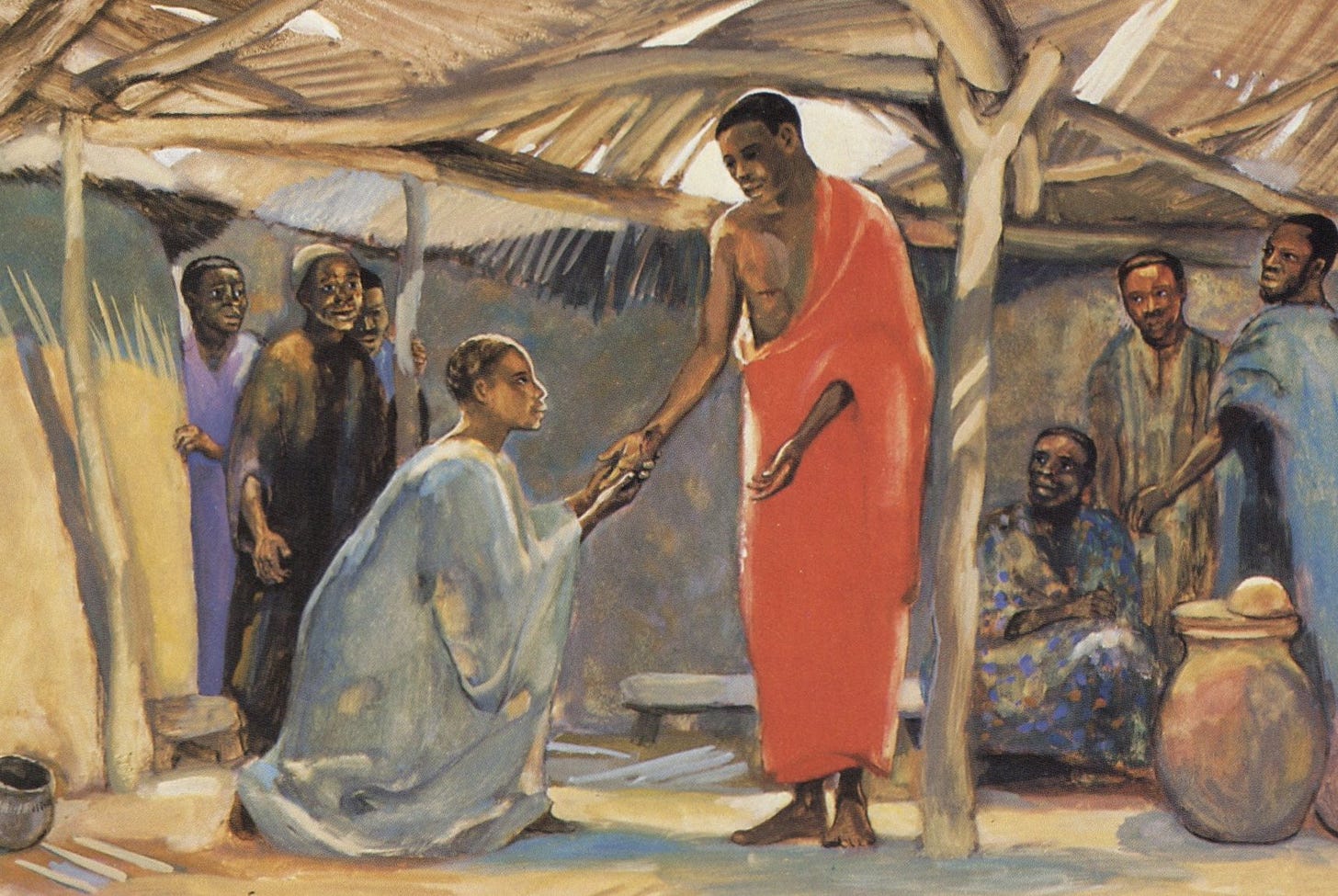

Art by the Jesus Mafa Project.

Thank you for your thoughtful essay, and for the unexpectedly delightful accompanying artwork which at first glance surprised me, then learning about the project I found to be so inspirational. Funnily enough, just recently my 3-year-old granddaughter and I found a squirrel in the same circumstances. Our conversations took a similar direction, although I'm not sure I did quite such a good job of answering her as you did!

"Jesus comes back to a body. To pain and suffering. To fatigue, hunger, desire." Whait what? I'm confused. I thought when we get resurected we will be done with pain and suffering and all those annoying mortal things.