Awakening to the Suffering Body of Christ

My grandfather didn't see the births of his six daughters. The first was because he was posted to a Canadian Air Force training base during World War II. The year was 1944 and he was allowed home on one harvest leave, hoping it would fall on the due date, but the harvest came and went and the baby never arrived. She was born soon after a desolating farewell at the train station. He did come home at Christmas to hold her for the first time and bless her at church, but he was called away again after just one day. My grandmother says his hands shook when he held her.

When their second daughter was born, the war was over and my grandfather was on campus studying dentistry. It was the time of the great baby boom and the hospital had to be set up with plywood partitions in the hallway of the maternity ward to accommodate so many births. The school posted a note to announce his baby on the student bulletin board between classes, but they accidentally printed that she was a boy. My grandfather never did get a son. This was hard for him, although he always said he loved his daughters very much. At the end of a meal, my aunts laugh to tell me he would sometimes beat his chest like Tarzan. As a young father especially, he didn’t always know how to act when surrounded by so many women.

My mother came next. When she was born, the telephone operator was asleep at the switchboard, so the nurse was unable to call for the doctor to come to their small rural hospital, but my grandmother said it was better this way. Just her and the nurse. It was the night of the winter solstice, and they said a prayer before working through the labor pains, breathing together. My grandmother’s eyes are wet when she tells me this. My mother was born at three in the morning, which happened to be the precise time of the solstice. From that moment, the world literally started getting brighter. I think about that sometimes, these two women laboring in the darkness of a world still recovering from war to bring my mother to the light. I wonder who from heaven was watching. Perhaps my seven siblings and I were allowed to watch, singing a heavenly chorus for them right before Christmas, like the angels did at Bethlehem. But my grandfather didn't see or hear anything, because he was asleep.

According to my grandmother, he did not attend the births of his last three daughters either because he felt uncomfortable. "I've already seen it with calves on the farm," he once told her. She begged him to come in for the youngest, to have this last chance to witness what she went through, to say in effect, "Come and see how much I suffer for your children." But my grandfather didn’t want to come and see. I can give him grace for that, since it was the prevailing attitude of his generation. In most cases, fathers weren't even allowed in. So for that last birth he stayed outside the delivery suite, cracking jokes with the hospital staff. My grandmother was trying to focus on pushing and felt irritated by their jabbering outside, so she shouted at him to be quiet.

Before performing the atonement, Jesus Christ took his disciples to an upper room and gave them the sacrament. "Take. Eat. Do this in remembrance of my body." Then, "Take. Drink. Do this in remembrance of my blood." He showed them the symbolic framework of what He was about to do before having them witness the atonement in the most visceral way possible—to see Him deliver His children with His own flesh and blood. With the bread and wine still digesting, He invited Peter, James, and John to the garden of Gethsemane to see Him bleed from every pore. Later, they were invited to witness His body being broken on Calvary.

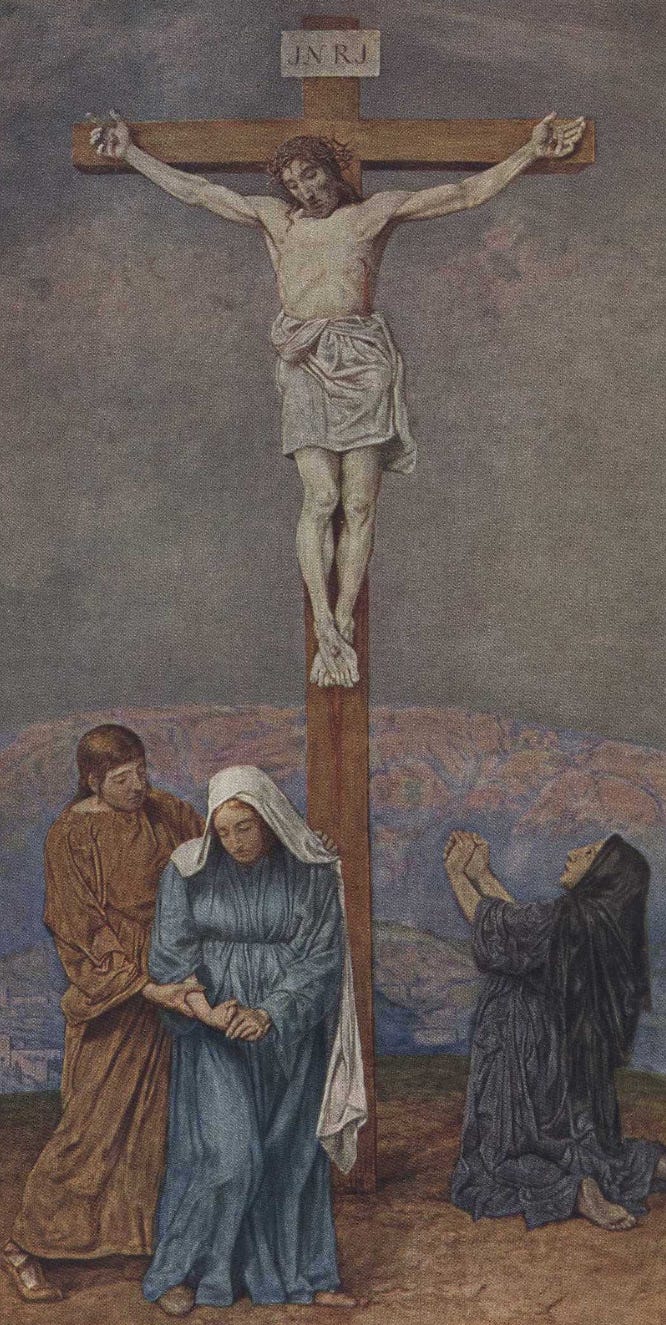

I imagine these acts at Gethsemane and Calvary as something akin to the labor pains of childbirth. Crowning, but with thorns. All He asked of them was to watch with Him, and to not fall asleep. Three times He asked this, but the disciples could not stay awake. "The spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak" (Matt. 26:41). Later, John was there at the cross. He was called "beloved" and listed with women who kept vigil. The women never fell asleep. It was there that John was told by Christ, “Behold thy mother” (John 19:26–27). Jesus was talking about Mary, of course, but perhaps in another sense He was also talking about Himself, asking John to behold the Messiah who was, in that very moment, acting as surrogate mother, bearing and delivering His children from death and hell on the cross.

Like someone invited to the delivery suite, we are also called to stay awake and watch the suffering of the body of Christ. The suffering of His physical body is finished, but the suffering of His metaphorical body—the suffering of His children—continues today. Paul taught, "Now ye are the body of Christ, and members in particular" (1 Cor. 12:27). As members of the body of Christ, we will not sleep through our own deliverance this time. How do we learn to stay awake for the suffering of the body of Christ? We can start by acknowledging the pains that exist among members of our church community.

As members of the body of Christ, we learn to be in tune to the suffering of God’s children. Latter-day Saints know that a common mandate in the scriptures is for us to "awaken." In the temple endowment ceremony, it is the first commandment given in the garden: to "awake and arise." Being "awake," especially when it comes to the suffering of another, is a key part of discipleship. We work hard not to fall asleep in the Gethsemane of others. We learn how to witness the suffering of the body of Christ as we are spiritually born again. For my grandfather, this happened gradually over a lifetime of church service. After missing his children’s births, my grandfather later served as bishop, stake president, temple president, and finally a patriarch. He spent most of his life sitting up on the stand. As the father of the ward, he presided and witnessed as the blood and water of Christ's deliverance flowed out from the sacrament table on the stand next to him. He witnessed the spiritual rebirth of many. One way or another, God was going to make him see.

Times have changed since my grandfather missed the births of his children. In some ways, the world is more awake now than it ever was. In many families, men are more involved in the raising and nurturing of their children than ever before. When my wife shook me awake in the night and in her own way said, “the hour is come” (John 12:23), it was expected that I would follow her into the delivery room. These experiences changed me forever. Each contraction was a call for me to wake up and witness the pain of their mother. The tearing of her flesh and gushing of her blood made my minor inconveniences in the birthing process (like sleeping on a hard foldout hospital chair) seem silly. Being a witness to her suffering, rather than a spectator, strengthened my resolve to ensure that whatever happened in raising these children, we would work hard to do so as equal partners.

In the scriptures, conversion is compared to a rebirth. We are invited to be “born again” in the Church of Jesus Christ by making covenants that invite us to become a part of a greater whole. In other words, we are born into a collective body of saints, not an individual salvation. Like birth, spiritual rebirth can also be a painful experience, but it is a key part of our baptismal covenant to become a part of a larger community that is willing “to bear one another’s burdens . . . to mourn with those that mourn; yea, and comfort those that stand in need of comfort” (Mosiah 18:8–9). The sacrament is a renewal of that covenant and also points us toward collective wholeness with the larger community. As we take the sacrament each week, the living body of Christ is reborn through us. The body of Christ that was broken for us is gathered together and made whole, albeit momentarily, in the lives of its members, “that they all may be one; as thou, Father, art in me” (John 17:21).

The process of a rebirth into a collective body sometimes means feeling pain that does not originate in us, because an injury to one member will affect the whole body. For example, one Sunday I was asked by a young priest to help bless the sacrament. I was feeling heavy that week with the news of loved ones who, for understandable reasons, decided to stop attending church. As I stood to tear the bread representing the body of Christ, it was like tearing my own heart into pieces. Pondering on Christ’s ability to heal physical bodies, I wondered about His own metaphorical body, which still seemed so stricken with spiritual leprosy as marginalized members I loved kept falling off. I thought bleakly, "Physician, heal thyself" (Luke 4:23). As I considered the pain of Christ’s weekly dismemberment, I watched the deacons file back up to the stand with the leftover bread and water. Those unconsumed pieces seemed to symbolize those who, even if they were not “re-membered” back into the loaf of Christ’s body that week through church participation, were still always a part of Him. I was pricked to consider the ways I was commanded in the sacramental covenant to “always remember” those not fully integrated into the body of Christ, and to consider what I could do to keep that covenant with more love.

As the body of Christ is "re-membered" and made more whole, and as we learn to integrate with each other in all our differences, there will certainly be grief and difficulty along the way. There are times when I feel like my efforts to serve are not preparing the body of Christ for resurrection, but rather for its burial. Some days I feel like Mary, anointing the feet of Christ with a pound of spikenard and wiping it with my hair, while others who watch me may wonder if my efforts are better spent elsewhere (John 12:1–8). Why should I waste my time and money on a body as complicated as this church? But Jesus answers this question for me, "Let [him] alone: against the day of my burying hath [he] kept this" (John 12:7).

As my grandmother was passing away earlier this year, I thought a lot about the stories she had told me about the births of her children. I sat with her as she labored quietly through a different kind of delivery this time—her own. I saw how similar birth is to death, these two entrance and exit points through the veil. I gave her one last priesthood blessing and we told each other how much we loved each other hours before she faded out of consciousness. As she labored again, this time awaiting a different passage through the veil, I thought: “This time, I will watch with her. I will stay awake.” With my mother, we turned her from side to side, moistened her mouth, cleaned her up, and held her hand. As a registered nurse, I drew up the morphine, monitored her pain, and counted the respirations. I sang hymns to her with my niece and oldest son. And then, I went home to sleep. When I got the call in the early morning that she had passed in the night, I was struck with several different emotions all at once, including guilt. Guilt that my mother and niece were there to witness her as she labored through the veil, but that I was asleep. What does it mean for me, for all of us, when we fail to witness the suffering of those we love the most?

Like the women who wept at Calvary to watch their last hope crucified, our hope can be tested to its limits as we witness so much suffering in our congregations. Other times, the suffering is our own, as we are called to labor through our darkest night alone; like my grandmother, we may experience times when it feels like God has fallen asleep at the switchboard. But as we continue to stand as a witness to the suffering of others, we can be spiritual midwives and midhusbands as we work together to deliver Christ’s own body, which in turn allows for our own spiritual rebirth. Our shared labor pains will keep us awake, binding us together with His love. Like Mary standing outside the empty tomb, we will be awake and ready to meet our Deliverer in the morning when He comes.

Christopher is a poet, writer, nurse, husband, and father of five. He lives in Raymond, Alberta, Canada.

Art by Hans Thoma.

KEEP READING

NEWS

Restore is this week! Register with the code WAYFARE for a discount.

Sharpen your pencils, and come join the fun! With a submission deadline of October 15, 2024, the Mormon Scholars in the Humanities and the Association of Mormon Letters welcomes any and all submissions on the 2025 theme "Cultivating Mormon Literature and Other Gardens" for their joint conference keynoted by Michael Austin at Snow College in Ephraim, Utah on May 28-30, 2025. The (playful!) full Call for Papers can be found here.

In her book, Sacred Struggle, the late Melissa Inouye writes: “The place of alienation is familiar. All paths through eternity loop through here, more often than any of us would like… Christ was here. This place is sacred.” Next year’s Global Mormon Studies online conference, taking place in Spring 2025, embraces these themes of alienation and marginalization within Mormonism. Paper submissions will be accepted until October 25th, 2024.

The Howard W. Hunter Foundation through Claremont Graduate University’s Mormon Studies program will be hosting two events addressing “The Future of Our Faith” from September 13-14th. Moderated by Matthew Bowman, Latter-day Saint theologians Adam Miller, Rosalynde Welch, and Joseph Spencer will offer discussion, mingling, and desserts in this special panel event. Zoom options will be available. For more details, and information on suggested donations, see the following.

The New York Times recently published a short piece overviewing the role of indigenous artwork in Latter-day Saint missionary efforts in the remote Australian Northern Territory communities. “Historically, Aboriginal languages had no written form. Therefore, said Gary Bird Mpetyane, a Mulga Bore Mormon Church leader, visual symbols were baked into the culture, easily recognizable and instantly relatable.”

Amazon’s “Rings of Power” showrunner and Latter-day Saint screenwriter, J. D. Payne, reflects on how his mission experience and faith have shaped and benefited his career in this Church News article. “In the times I’ve tried to be the most spiritually in tune, the Lord is with me and is able to do miracles I could never do on my own” he says.

This is lovely Brother Bissett. I can relate as a mother and as a disciple trying to always remember Him.