At the Threshold of Heaven

Entering the Wholeness of God's Love

This is the covenant that I will make with them after those days, saith the Lord, I will put my laws into their hearts, and in their minds will I write them;

And their sins and iniquities will I remember no more.

Now where remission of these is, there is no more offering for sin.

Having therefore, brethren, boldness to enter into the holiest by the blood of Jesus,

By a new and living way, which he hath consecrated for us, through the veil, that is to say, his flesh;

And having an high priest over the house of God;

Let us draw near with a true heart in full assurance of faith, having our hearts sprinkled from an evil conscience, and our bodies washed with pure water. —Hebrews 10:16–22 (KJV)

Like many women of my generation, I received my Latter-day Saint temple endowment the day before my wedding. The year was 1983, and I’d prepared in the same way many of us did: by reading Elder Boyd K. Packer’s short pamphlet titled The Holy Temple. I don’t recall much about the booklet; the pictures were pale and quiet, the text somewhat vague. I felt unconcerned about the experience I was about to have. Mostly I was excited about getting married.

As we shopped for travel supplies in a Woolworth’s, my fiancé told me that there would be a moment when I’d have a chance to back out of the temple covenants I was about to make. This surprised me. What was I in for?

“Don’t do it,” he said. “If you leave at that moment, you may not get back in.” I wasn’t sure what he meant. But we’d spent our several-month engagement apart from one another. He’d stepped off a plane a day earlier, without friends or family, crossing the country to my hometown of Pittsburgh to marry me. I was so thrilled to be with him that I tucked his advice in some untended fold of mind and gave him a reassuring hug.

We traveled several hours to the Washington DC Temple a couple of days later with my faithful parents, their parents, and some of their friends. I am the oldest child in my family, and I had no previously temple-endowed friends or siblings with me. The initiatory and endowment experiences left me surprised, unsettled, worried, and even dismayed. I couldn't stop crying. And I wasn’t sure I wanted to go through with our temple sealing. I felt peaceful only when I thought about getting beyond the next few days, about finishing what was needed in order to marry my fiancé. I tried to put the temple out of mind as we began our lives together.

Over the ensuing years, I tried for a détente with the temple. My lifelong faith and cultural tradition were persistent, but the temple wasn’t a large part of the way I experienced them. As with polygamy and other uncomfortable features of Mormonism, I kept the temple out of mind. I attended only occasionally.

This is a familiar story, I’ve learned. My discomfort was not unique, and it was not for nothing. Changes to ordinance wording over time were helpful. I rejoiced when some of the now-disappeared, difficult language finally vanished from my mind at key moments in the endowment presentation. I was grateful that some of what bothered me had been removed by the time two of our sons received their endowments in preparation for their missions.

I came to appreciate initiatory sessions after adjustments to the ordinance were implemented. I loved the feeling of sisters’ hands on my head and the blessings pronounced. One beloved sister, a dear friend of mine, recently placed her hands on my head and anointed me as a “princess” in a slip of the tongue. I treasured this unique language because I loved this sister so much.

But the peace that others spoke of—the joy and strength they found in temple worship and temple service, the anticipation and hope with which they approached a few hours at the temple—has continued to elude me. On the rare occasions I spoke of it, my parents and others encouraged me: keep going. My husband understood my anxiety and perhaps had foreseen it, with his “don’t back out” comment in Woolworth’s. As the only active LDS participant in his family, he wanted this life of faith for us, even as he could see that it would not always be an easy acquiescence for him or for me.

Through these decades, life did what it does. Our family experienced plenty of trauma and heartache, alongside abundant joy and satisfaction, much of this happiness connected with the covenant path. For a few midlife years I strayed from this path, only to discover that I was a little too Mormon to stay away. I loved the gospel, it turned out: the language of the scriptures, the hope in the Savior’s teachings and Atonement, the lift in so many of the meetings, the joy in family and community and discipleship. My faith was strong, even if a little fringe when compared to the mainstream.

I began to see the temple as a place to connect with ancestors I hoped to know one day. I saw it as an opportunity to try for increased faith and for living with more intent. I found the Spirit there occasionally; but in the majority of visits, the heavens seemed closed to me. I continued to encounter temple worship as a challenging part of my faith: a place to try and submerge—since I couldn’t reconcile—perceptions of problematic language, gender and cultural difficulty, vagueness, and my own impatience. It remained an experience to endure. My difficulties have been deeply considered, including hours of ultimately unsatisfying research and study; but they could also veer into the trivial (would the veil worker have clean hands, for example).

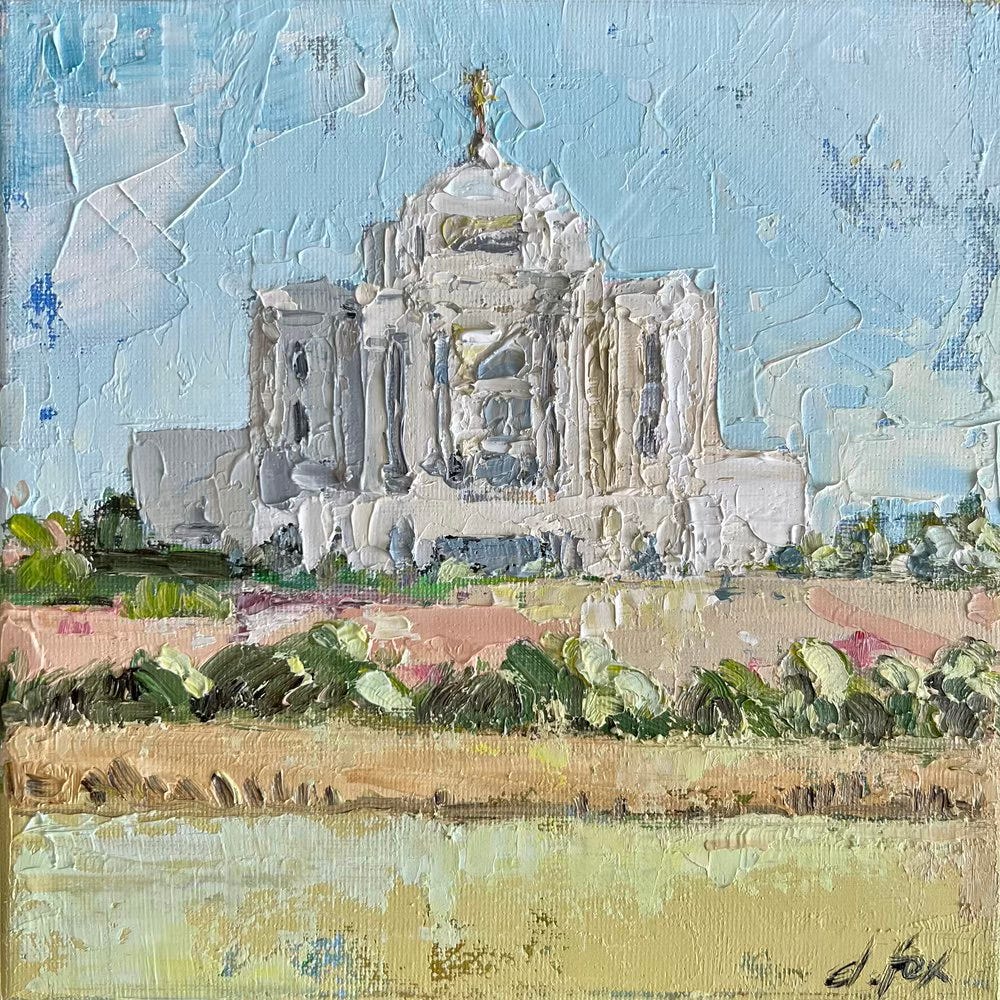

Recently, nearly forty-one years into this uneasy temple relationship, I attended a noon endowment session at the Meridian Idaho Temple. I served as proxy for a distant relative of my husband’s, one Ann Chapman, born in Yorkshire in the seventeenth century. My own Boise temple had closed for renovations, so the Meridian temple was crowded and busy. Though I thought I’d arrived early enough, I was delayed because I had trouble finding an available locker.

Getting from the locker room to the chapel was full of obstacles, from long lines to a wedding party blocking the staircase to a busy elevator moving in the wrong direction. When I finally reached the chapel on the second floor, it was a minute past noon. The room was crowded, too warm, and full of chatter. I was shown to the far back, meaning that I would also be one of the last to finish the session. Several patrons entered the room after I did; the session was running well behind schedule. I was feeling impatient, petty, and full of growing dismay.

I prayed for peace and understanding. As the session began, I noticed that the film selection was my favorite, featuring an actor I call “Emotional Eve.” I tried to pay close attention and also think about Ann Chapman; I asked the Lord to tell her hello and convey kind wishes from me, to make her aware of what was happening. I prayed for my family, each one by name, for love and joy and safety during our coming gathering, for each of them (not all of them participating in church) to feel the guidance and protection of the Spirit, for their success and happiness, for the health of my husband and his business, for friends I knew were in difficulty. I prayed for the Spirit to touch and teach me, for help in bearing more effective witness.

Despite my rocky start, once inside the ordinance room I was able to focus on the covenants—obedience, sacrifice, gospel, consecration, chastity—all covenants I have struggled to keep, but have tried to embrace. I thought of how much better my life was when I was intently walking the path, despite its constraints. I participated in the prayer circle, even though I knew no one in the room. I was almost to the finish line!

I settled in for a wait at the end of the session. Progression to the final portion would be slow. I hoped to feel the Spirit, something I have been determined to welcome but not insist upon. I glanced at my watch. The impatience I’d worked to tamp down was bubbling up again, as, I realized, it just continues to do. All of my progress seemed to be draining away.

And then, finally, it was my turn to approach the veil.

Recent visits to the temple have surfaced the teaching—it seems newly prioritized to me—that the veil represents Christ (see Hebrews 10:20). We are taught that the endowment is a gift from our Heavenly Father, and the veil, by which we receive the culmination of that gift, is Jesus Christ.

I stood—beyond all the delays and obstacles—I stood to receive, through the Savior, the gift Ann and I had come for. And something changed. The purpose, I could now see, of the entire experience was to receive this bequest—and I heard its presentation in a new way. The language of the gift mentioned everything I could want. I couldn’t imagine the desire for anything else, really. Other interests fell away—continue to fall away—into irrelevance. This bestowal is truly all that the Father has. It is perhaps an articulated definition of eternal life, the greatest of the gifts of God. When we speak of being heirs, children of Christ; the devotees, the disciples, the delivered; covenant offspring who are promised all that the Father can give, this is laid out—expansively, in succinct, beautiful language—to the individual in an intimate whisper at the veil. To receive this inheritance, I could finally see, was simple: Return and reclaim the covenant path. Honor the promises you have just made. Keep Christ always at your side and in your heart. Pass through him to greet the Father and receive. In the context of bequest, we come to the Father only through him.

This deeper understanding covered me with a beneficent light. It wrapped my shoulders in emotion, making my body tingle. I was overcome with a feeling of love. I felt small, yes, inadequate, sure, but also precious and treasured. I sensed a deep and reliable assurance. My tears began to fall.

Father, I whispered, energized, alert and awakened as I sat in the sparkling celestial room: Is this the peace that others speak of? It’s taken me forty-one years to receive this perception that has apparently always been here, waiting for me to find it. I am here, as you are here. I will walk this path with new resolve. I will continue to show up. I will travel forward with greater confidence and less concern. Thank you for this journey and for your infinite patience for a struggling daughter who easily loses her way. I feel the love which you somehow press through all barriers of self and custom to bestow. I receive your love with joy and boldness. I draw near, I return it with a true heart in all patience and faith.

Heidi Naylor is an Idaho-based writer of stories, essays, and poems.

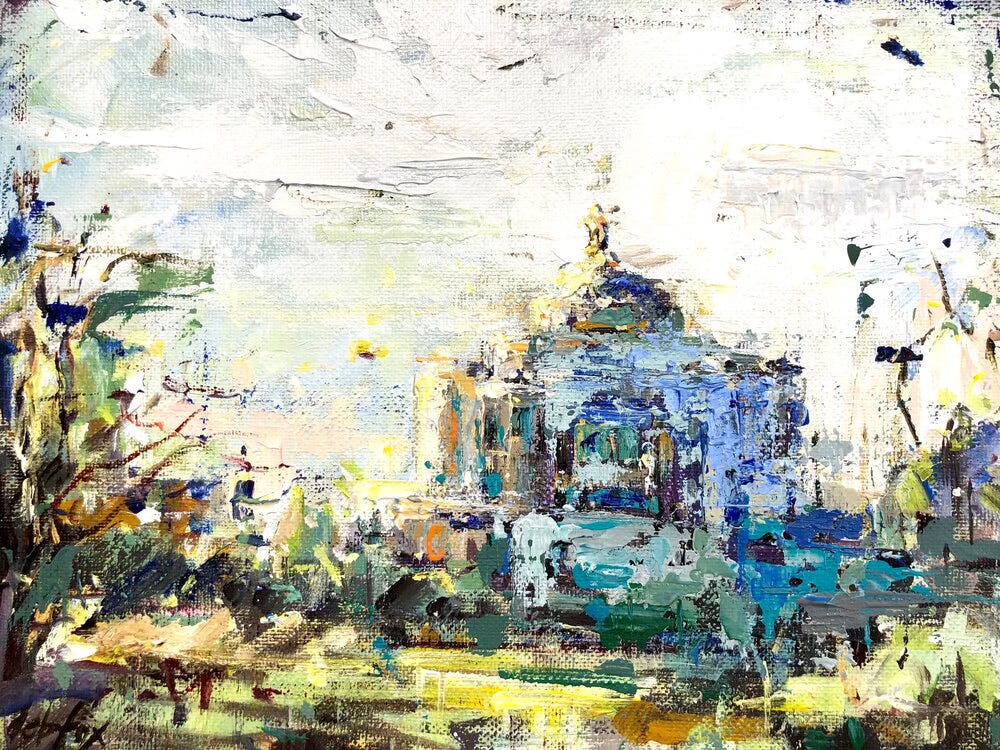

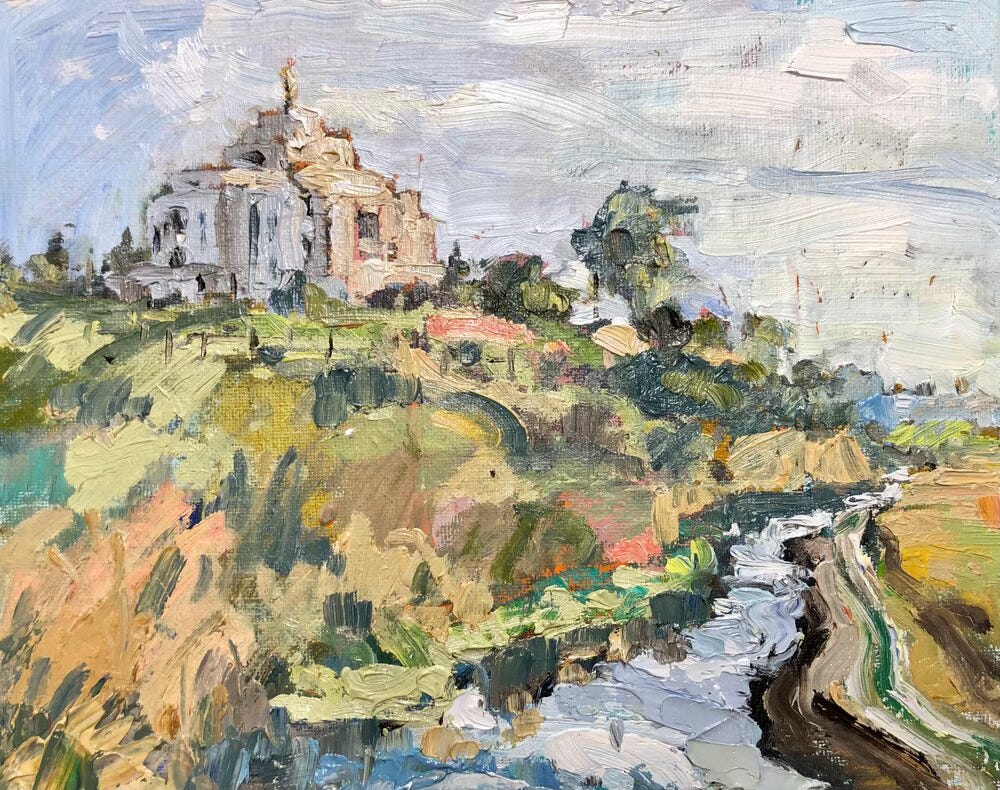

Paintings of the Meridian, Idaho temple by Deb Fox.