Anxiously Engaged

In Weakness, Strength

I’m trying to remember the moment when I realized that I am an anxious man. When I was growing up in the 1970s and as a young adult in the 1980s, we never talked about “anxiety” as a mental health issue, and so I assumed that my way of experiencing the world was not unusual. The moment of realization may have been the first time one of my children, all of whom have inherited my anxiety to some degree, began to demonstrate anxiousness. Or it may have been when I was sitting in Elders Quorum and received a new home teaching assignment to help someone I did not know. Or perhaps it was shortly after I finished my PhD and started attending academic conferences. While my best friend from graduate school moved through these conferences with ease, I struggled to feel comfortable. When we attended a conference reception, he was quickly involved in a conversation or two, while I hovered at the edges. In fact, if I met someone at a conference, it was usually because he introduced me.

I have trouble pinpointing my moment of realization, because although when I reflect back, I can see that I have been anxious for as long as I can recall, for many decades I was not aware that I was “anxious.” I simply assumed that others felt the same way about meeting new people or confronting a difficult social situation but that they masked it, as I usually tried to do. Only gradually, and with increased awareness of anxiety as a mental health issue, did I realize that I was in fact suffering from anxiety, that I am an anxious individual, and that my way of seeing the world is not as common as I had assumed.

When I am asked to describe what my anxiety feels like, I usually say that it is a lot like fear. The two feelings, in fact, are so similar that I am tempted to say that anxiety makes me a coward. There’s a good deal of truth in that statement, although it is nothing like the whole truth. At certain moments in my life, for example, I have done something awkward or foolish, have felt embarrassed and ashamed, and so have realized my worst social fears. But that’s only the beginning of the experience, as the shame and embarrassment persist; I relive my actions, as well as the moments leading up to them, wishing that I could go back and make a different choice, or perhaps avoid the situation altogether. For a time, it seems like I live in shame, breathe it every minute of the day, and the only thing that I am able to think and resolve is: I will never feel this way again, not if I can help it.

Indeed, I have learned that whenever I contemplate a new and therefore anxiety-inducing situation, my mind immediately assumes the worst possible outcome—an outcome, when seen from any rational perspective, has a minuscule chance of actually occurring, but one that in the moment of anticipation seems all too likely. To return to the academic conference, if I meet a scholar whose work I have read and admired, I imagine that she will scorn my work, and that I will compound things by making a social mistake, and as a result she will spread her dismal opinion of me throughout our small scholarly community. Of course, things never proceed according to my worst imaginings, but that does not stop me from assuming the worst the next time I am confronted with a new social situation. And so, my “fight or flight” response invariably defaults to flight.

And in addition to cowardice, the frequent practical effect of my anxiety is narcissism. It’s so hard to get out of my own head that I have difficulty thinking about anyone else. As my daughter put her experience with anxiety to me one day, “my brain is so loud.” A couple of years ago, I struggled with an inability to talk to a young man in my ward who had strayed in a public way but who was nevertheless brave enough to come back to church. As I thought of approaching him, I ran through various scenarios in my mind, most of which involved putting my foot in my mouth and perhaps in some strange way indicating that I approved of the particular way he had strayed. And so I stayed away—ashamed but caught in a web of my own conflicting thoughts. I was describing this situation to my therapist, and he illustrated it by drawing stick figures of people facing each other in conversation; he then drew thought balloons over their heads, not to indicate words or thoughts, but instead to represent their focus of attention. Most people, or at least loving people, direct virtually all of their attention to the person standing in front of them and so have only one “focus balloon” over their heads. They don’t get lost for words because they are engaged with the person in front of them, seeing what that person needs. I, however, have two focus balloons. The one in front, the one directed toward the person in front of me, is small, since it represents only about 10% of my attention. The one that represents the other 90% is directed inwards, back onto my own mind, as I keep fretting and turning over possible scenarios and words in my head but not actually saying anything. It is no wonder that I find no words to speak, because I’m not actually thinking about the person in front of me but about my own worry, my own fear of doing something awkward or embarrassing. And so all too often this worry leads me to hang back.

There is a passage in Bruce Hafen‘s biography of Neal A. Maxwell that resonates with me in a surprising way. It’s early in the biography, but it recounts an event late in Elder Maxwell’s life. He has been diagnosed with leukemia and is about to check into the hospital to undergo a brutal series of treatments that are not much better than the cancer itself. As they park, Neal takes his wife Colleen’s hand and says, “I just don’t want to shrink.” I share Elder Maxwell’s worry; I too don’t want to shrink, although I am not facing anything as daunting as the leukemia treatment awaiting Elder Maxwell. And yet my natural response often is to shrink, to slink away when confronted with a challenging situation, assuming that I will not be able to handle it and will end up embarrassing myself and making the situation worse. I need to actively fight my natural desire to shrink.

And yet the idea that anxiety makes me a coward and a narcissist is also false, utterly false. Because I do not believe, in my case in any event, that my anxiety is such that it overwhelms me to the point that I no longer have a choice. I will at times let myself off the hook for failing in a social or ministering situation, but I don’t think God ever does. By that I don’t mean that my failure is unforgivable, but simply that He always wants me to do more and be better. Anxiety, to put it another way, is simply the condition of my life, and I have learned that there are ways to deal with it.

Several years ago, I was in London on a research leave to work at the British Library. I had a regular practice of a morning walk to Holland Park—one of my favorite places in London. At least half of the park is wooded, and for a brief time you can feel like you’re not in the city. On the edge of this wooded section is the Kyoto Garden, a beautiful and serene space constructed by a Japanese landscape designer as a gift from the city of Kyoto in honor of the friendship between Japan and Great Britain. Without fail, I ended up in this garden, and when I found myself alone I would often sit for a while and pray. With some exceptions, I am not very adept at prayer. My mind is too loud, it wanders too incessantly, and I find that I have a hard time making a connection with God, since my thoughts all too often bend back to myself. But occasionally, sitting in that beautiful place, out of doors, I was able to direct my attention away from myself enough to engage in meaningful prayer. I remember one morning in particular when I expressed frustration with my anxiety and with my seeming inability to improve, wondering why my anxiety always seemed to get in the way of any serious progress. Why wouldn’t the Lord simply lift my anxiety from me? As I spoke my complaint, the thought came to me unmistakably—your anxiety is your cross, your thorn in the flesh, and you will have to carry it as best you can.

And as I have tried to lift this cross through my sixty years of life, I have found that the best way to carry it is to be an active member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, to be engaged as fully as I can, even if that engagement is almost always fraught with anxiety. At first, this may well strike readers as strange. As I have visited with other anxious people who are active in the Church, I hear concerns and even complaints that resonate with my experience. What about the charge to get out of your comfort zone? Well, what if your comfort zone is not all that comfortable? What if going to church and doing what you already do makes you uncomfortable? Doesn’t being engaged in the Church exacerbate anxiety? All I can say is that in my experience, the answer is no.

Part of this is due to the unexpected fact that my anxiety lessens as I occupy a particular and defined role. For example, if I were asked to name an activity that would create the most anxiety for me, it might well be going door-to-door and talking to people I don’t know about something that they don’t want to hear. This most anxious of activities, however, describes the vast majority of my days in the France Paris mission. And yet, once I shifted into that missionary role, I was able to knock on doors, talk to people on the street or on the train, and not be debilitated by anxiety, as I felt that I was acting as a missionary was supposed to act. Similarly, when I was called as the bishop of my home ward, I found it easier to approach a member’s home and knock on the door with no prior notice, because, after all, that’s what bishops do.

I have already described how much of my life has an undercurrent of fear, and how often my initial response is to do whatever it takes to get out of an anxious situation, and yet being called as bishop (or a missionary) is to be thrust into countless anxious situations. Indeed, wouldn’t my default flight response help me here, simply by allowing me to say no to the calling? When the stake executive secretary called me on a Saturday morning many years ago, asking my wife and me to meet with the stake president the following day, I knew what he was going to ask me to do, and I spent a rough night, sleeping little as I wrestled with the calling I knew was coming and wondered if I could say no to it.

In addition, the bishop who preceded me was Matt Holland (now Elder Holland of the Seventy), and he was a remarkable bishop. I had a close view of his talents and devotion as I served as his first counselor. When I learned that he would be moving out of the ward and so would need to be released, I remember thinking that I pitied the man who would be called to follow him. And yet here I was. As I was getting dressed on that Sunday morning, I had a strong spiritual impression that this calling came from the Lord, and that I should accept it; flight was not an option. When I met with the stake president later that morning, and he extended the call, he advised me not to try to be like Bishop Holland but to find my own way. “Ah,” I remember thinking, “that advice will be easy to follow,” since I had no illusions about my ability to imitate Matt. But I also knew that for members of the ward, Matt’s release and my call would be a disappointment, and another cause for my anxiety.

And so when I accepted the call, I realized that I would need to remember that spiritual impression I had on that Sunday morning: for some reason, the Lord, knowing my anxiety as well as everything else about me, had called me, and I needed to trust in that understanding. I therefore made a determination that while I was bishop, I was not going to let my anxiety rule my life. I fulfilled that determination fitfully and imperfectly, but for periods of time, I found myself, I won’t say comfortable in the role of bishop, but able to fulfill the calling with some effectiveness. One of the things that I learned to appreciate in being a bishop was that the “flight” response was ruled out, and not only when I was first called. Throughout the time of my call, I needed to sit down and listen to people while they talked through the challenges and heartbreaks of their lives and to have faith that I could help. Still, after every Sunday afternoon and Wednesday evening of interviews, as I drove home from the bishop’s office, I would pray that my anxiety and other shortcomings would not adversely influence those I had counseled.

There were even times that my anxiousness helped me in my calling, as my lack of confidence in knowing how to help people or what to say made me rely more fully on the Lord than I had at any other time in my life. When baffling situations confronted me, if I would remember the impression that the Lord had called me and wanted me in that particular position at that moment of time, I would ask for help, and an answer would come. I remember a few instances when I was counseling with an individual over a difficult situation or question, and in my flippant way prayed silently, “You’ve got to help me here, because I got nothing.” And then suddenly, I found myself saying something that helped or that provided an answer to the question we were considering.

There is a passage in Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s book, The Cost of Discipleship, in which he seeks to lay out the difficulty and cost of being a follower of Christ and of avoiding what he calls “cheap grace,” the “grace” that demands nothing of the would-be disciple—no transformation and no repentance. And so he delineates all that Jesus asks of those who seek to be his disciples. As he points out, the demand is heavy, often extreme. But what, then, are we to make of Jesus’s saying, “my yoke is easy, and my burden is light” (Matthew 11:30)? Bonhoeffer’s answer is that only when disciples “unremittingly let his yoke rest upon” them does the burden become easy, “and under its gentle pressure [the would-be disciple] receives the power to persevere in the right way. The command of Jesus is hard, unutterably hard, for those who try to resist it. But for those who willingly submit, the yoke is easy, and the burden is light.” I feel the truth of Bonhoeffer’s reading, but I find it very hard to “willingly submit.” At times, it is excruciatingly difficult, since my natural instinct to hold back and shrink works against the demand simply to submit to what the Lord asks. But as I look back on my life, I recognize that when I have not followed my instinct to flee but have instead moved forward, trying my best not to resist Jesus’s command but to trust in his promise that his burden is easy, I have been most fully and effectively engaged in the life of faith—in the Church, in my job, and in my family—and somehow that life of faith has been easier than my usual practice of avoidance.

It has now been several years since my release as bishop, and ever since I have been seeking to exercise faith in the absence of such a demanding calling. We have, after all, agreed at baptism to represent Christ always, to “stand as witnesses of God at all times and in all things, and in all places that [we] may be in” (Mosiah 18:9). In retrospect, demanding callings helped me to channel my anxiety productively, as I did not need to make daily decisions about moving forward, even when it meant putting myself in anxiety-inducing positions; it felt like those decisions had already been made, and I had to sink or swim. As I leaned into the tasks of the calling, trusting in its inspiration, I found that more often than not I swam. I still felt anxious while doing so, but by acting in faith my anxiety became more manageable.

I have thought a lot about the verse in Ether 12:27, where the Lord tells Moroni that he will make our weakness become strong if we exercise faith. The Lord has indeed at times made my weakness of anxiety strong, but that has not meant—even in those moments—that I am no longer anxious. As the Spirit told me on that fall day in the Kyoto Peace Garden in Holland Park, I am not going to be relieved of this “thorn in the flesh.” But it can become strong, I have realized, when I refuse to use my anxiety as an excuse and instead exercise some faith that the Lord can use my anxiety in productive ways. I have learned that the Lord is intimately aware of my struggles, even if He does not relieve me of them, just as He is aware of my hopes and triumphs. And this is a lesson that we should all learn. The Lord in fact needs me as His disciple—precisely because of my anxiety or other weaknesses as well as my strengths—just as he needs all of us. For those of us who suffer with anxiety, the burden of faith indeed at times seems heavy, but by being anxiously engaged, the Lord uses even that anxiety to bless others and, in the process, to lighten my own burdens.

Stan Benfell is the director of the David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies and professor of comparative literature at Brigham Young University.

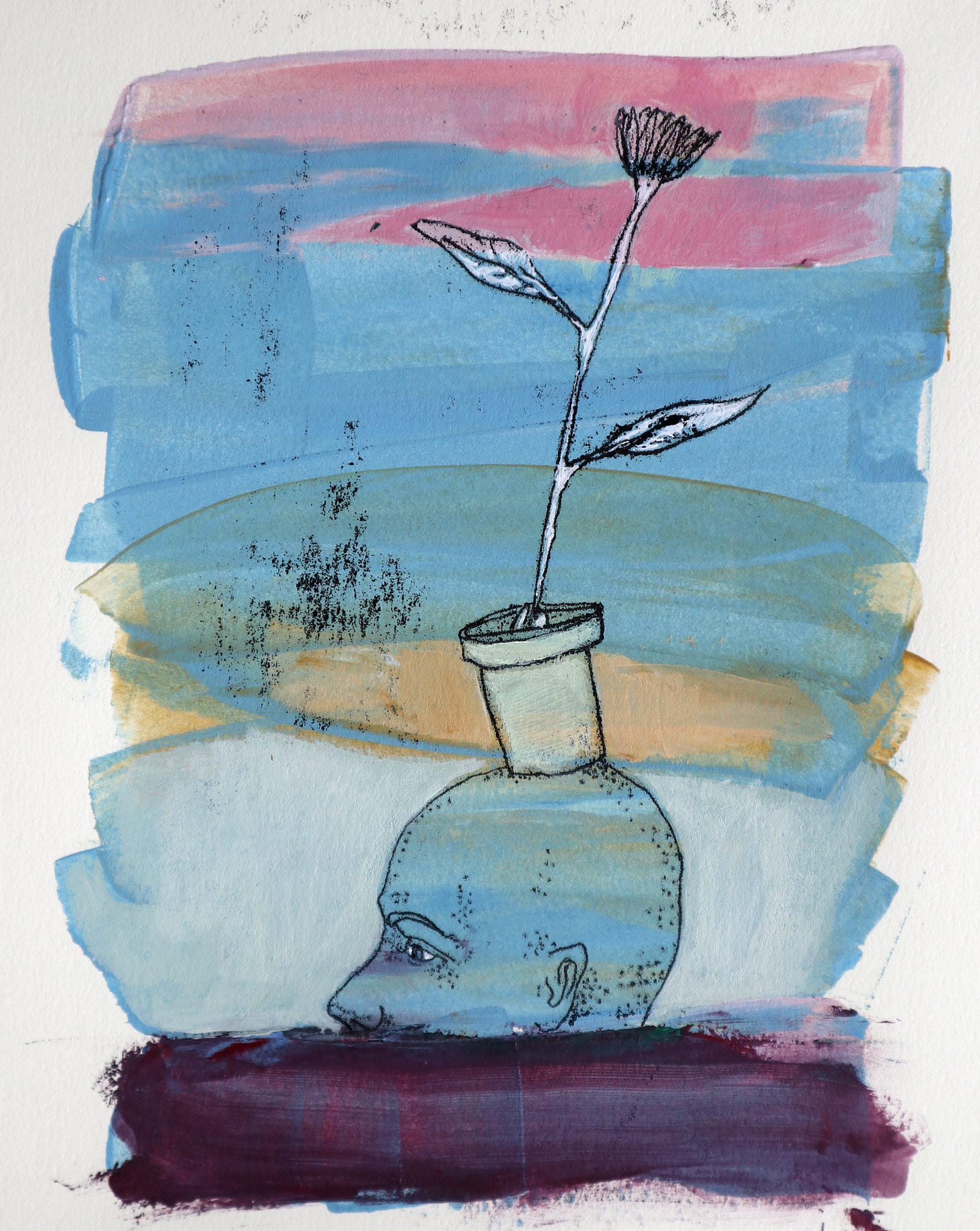

Art by James Rees.

KEEP READING

The Collector

People wish to be settled; only as far as they are unsettled is there any hope for them. - EmersonThink of it as a gradual gathering first placing objects more gilded than grey. The soft shelving of the delicate and crystalline, thin talismans, scalloped shells that hold the whole whispering cantorate of the sea. Now, add leaden questions and touchable…

What Are People For?

L. Michael Sacasas is the Executive Director of the Christian Study Center and author of the The Convivial Society, a popular newsletter on technology, culture, and the moral life. Wayfare Editor Zachary Davis sat down with Michael to discuss the meaning of technology, why limits are good for us, and how to stay human in a dehumanizing age.

NEWS

The Latter-day Saint Women Project is turning 15 and a special celebration in its honor will be held in Provo on June 28th. Project Founder, writer, and activist Neylan McBaine will share some thoughts and reflections, followed by a panel discussion with author, teacher, and graduate student Melinda Wheelwright Brown and author and women’s historian Jill Mulvay Derr. LDSWP Editor-in-Chief, Elizabeth Ostler, will moderate the panel discussion. Register to save your spot at givebutter.com/15th.

Published by Inkstick, “Cracks in the Sin Screen: The Link Between Mormon Tithes and Nuclear Weapons” explores the developing ways the LDS Church has responded to the intersection of nuclear weapons, finances, and its own commitment to Christian peacemaking. Its authors find that “Church-owned Ensign Peak Advisors holds Northrop Grumman stock — despite Latter-day Saints’ historic opposition to nuclear weapons”.

Scholars and writers Stephen Taysom, Gregory Prince, Lindsay Hansen Park, and Richard Saunders discussed the intricacies and art of Mormon biographical writing in an online event hosted by the University of Utah Press. They offer a critical examination of the genre all in celebration of the seminal biographies published by the University of Utah Press in its 75 years of publishing.

In case you missed it: the University of Virginia’s Mormon Studies Program has just released excerpts from the Gregory Prince Collection on the subject of "Priesthood and Mormonism. Explore over a century of primary source accounts of divination, patriarchal blessings, priesthood restoration, and so much more, all freely available on their website!

Thanks very much, Candice. It's good to hear from you, and I'm grateful for your comment, especially for sharing your own experience with anxiety. Hard to believe that it has been 15 years since you were at BYU!

I love this essay. I have struggled with social, health, and driving anxiety. I resonate with recognizing it for the first time as an adult, and with accepting it as a burden to bear for the long haul (although have been able to do things to improve it). I recently got a calling as choir director in my chaotic ward which has 100 investigators attending each week. Everything in me says "hell no," and yet the ward needs it, and it is in line with my values. Sometimes it feels bitterly ironic to me that God is aware I don't feel cut out for being the center of attention or being in charge of chaotic things, and yet keeps providing inspiration to do all kinds of things that are way out of my desired activities and comfort zone. I see exposure to ward community life really can be a great treatment for anxiety! Your essay made me think about how I've received many blessings that have said things like I'll lose my self-focus. It has always made me uncomfortable. My anxious thoughts may be about my own welfare in a lot of cases, but I've actually had the opposite problem in relation to other people. I give too much, and I have consistently underestimated myself and assumed I will fail at things that I succeed at. I think I actually needed more faith in myself, and in some ways more real focus on myself, not more unselfishness. Thanks for the generous essay. And it was delightful to hear about this more personal side of your life having known you (15 years ago) in person, without having any clue you struggle in the same way I do :)