“The destinies of thousands of other people were bound to be affected, some remotely, but some very directly and near-at-hand, by my own choices and decisions and desires, as my own life would also be formed and modified according to theirs. I was entering into a moral universe in which I would be related to every other rational being.” -Thomas Merton

I was asked recently if I thought the most sinister villains of history will eventually be forgiven and gain entrance to heaven. Serial killers, wanton conquerors, genocidal monsters—the human past and present are replete with characters who confound the calculus where human evil and divine mercy meet, where the harmonies of agency and responsibility and retribution and atonement become unfathomable, obscured by personal and vicarious trauma, the temporal finitude of our own powers of imagining, and the appalling magnitude of suffering. “Will the worst perpetrators be pardoned?” the student asked me. I responded that he seemed unhappy with that possibility. He said that he was. "Then they will not," I replied.

He thought he detected irony or sarcasm in the response, but there was none. Joseph Smith addressed the question at a scale more manageable. He said, “if you have no accuser you will enter heaven.” Most of us at one time or another have been unfairly accused: of sampling the forbidden dessert, when in fact it was our little brother; of an innocent remark taken as criticism; of a lapse of memory interpreted as conscious neglect; or of myriad slights, attitudes, tones or intentions that were figments of another’s imagination. Add to that the offenses we freely own, but which our pleas for forgiveness have yet to erase in the mind of the offended, and many of us have someone who nourishes an ill thought about us. Is it conceivable that one stubborn accuser can have veto power over our admission to heaven?

Framing the question in such a way reveals a set of presuppositions that I take Joseph to be calling into question, not far removed from myths about pearly gates, with St Peter (or surrogate) at the porter’s lodge, and a hoped-for pass inside. However, if heaven is largely a matter of sociality, and our eternal future a matter of association with those we love, then Joseph’s remark (and mine) might make a certain kind of sense. The same kind of sense that Thomas Merton was making, when he realized a human counterpart to the butterfly effect.

Until the late nineteenth century, mathematicians didn’t work much with the concept of infinity. Infinity seems to be self-explanatory as a mathematical concept. Endless is endless. George Cantor, a Russian-born German, used set theory to demonstrate a surprising fact: there are infinities of different size. (Real numbers and natural numbers are both infinite; but there are more of the first; The set of natural numbers and of prime numbers are both infinite, and both are, unexpectedly for most of us, equally infinite).

Maybe circles of love work in comparable fashion. A family can be whole and complete and joy-filled. Then another child pops into the equation. Adding a child to that circle doesn’t mean it was incomplete before, though that feeling is a common one with new parents, as it is with a lover or friend who enters our life. “I didn’t realize how incomplete my world was before, we may say”—and mean it. And that makes emotional sense. But we might say with equal truth, in response to the enrichment a new personality brings in their wake, “you have made my infinity larger.” Discovering a new friend, early or late in life, enlarges one’s earthly heaven. That doesn’t reflect back an incompleteness to one’s life previous to that friendship. It reflects two other truths: Heaven is eternal sociality with those we love. And infinite possible associations exist. With each person added to the mix, each new relationship formed, cherished, and nurtured, an infinite heaven becomes a new infinity.

We are, in an essential way, the ones who set the parameters of our heaven—assuming it is true that heaven is largely a matter of loving relationships. If I have an accuser, and that relationship goes unhealed, then my heaven is bounded in that direction. However justified or unjustified it may be, a grievance in the heart of the other impedes the reciprocity that I am seeking. It is a barrier to the ever-expanding universe of deeply connected humans I am trying to foster. In a similar way, if I nourish a grudge, ill-will, or mere dislike for another person, then I have limited that person’s heaven in my direction. It seems, in that sense, that it’s not simply a question of guilt or blame—heaven’s limits are ones we impose on each other—hence the surprising phraseology of Joseph’s pronouncement. Right and wrong matter. Virtue conditions our susceptibility to joy, and the peaceable things of the kingdom come to those of a pure heart. But if heaven is the set of connections in which we find ourselves, then we are its architects, and the blueprints we bring into being have no predetermined borders. Heaven will be an infinitude of expansive possibilities. But the size of that infinitude depends on all of us.

To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, first subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."

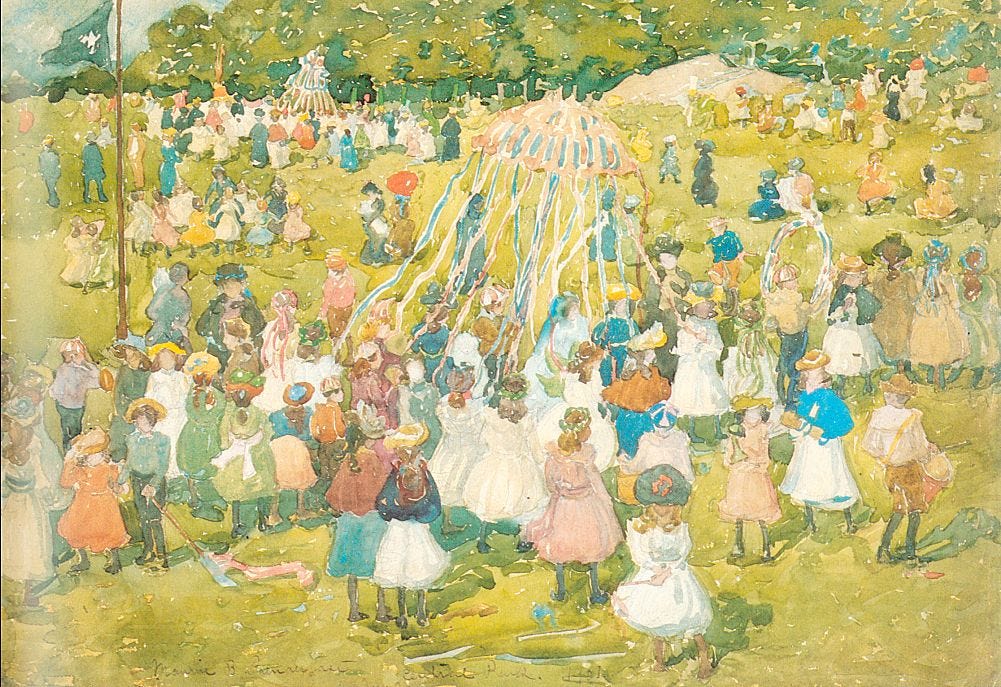

Artwork by Maurice Prendergast

What a beautiful description of heaven. This prompts some really healthy reflection about the relationships and priorities in my daily life.