I can’t remember the first year of my daughter’s life. I think, write, say those words and my chest tightens, grief and shame washing through my body. I can’t remember.

I can’t remember.

The hazy recesses of memory recall an urgent call to Heavenly Mother around this time. Maybe my spirit subconsciously knew to prepare for impending darkness, or perhaps I felt heightened stakes of raising a daughter in a world still burdened with patriarchy, but finding my Mother felt a life-and-death effort. If I didn’t find Her, would I ever find myself?

Eve came first, though, the Ursa Major guiding me to Polaris. Eve and her choices both fascinated and perplexed me. For years I’d wondered why God would give a commandment to Eve and Adam that they were destined to break, and why, if the Fall was both inevitable and essential, we would talk about Eve being tempted and deceived, when to me she clearly had the foresight and courage to be the first to step over the threshold into the unknown. With time, the temple endowment confirmed what I intuitively knew about Eve, but still I wondered: if we were to properly revere her, what changes would we see in how women interacted in and with our world? And furthermore, what parts of myself were already in a metamorphosis for simply choosing this knowledge?

Seeking Eve opened my heart to the divine feminine and unlocked spiritual access that had never been taught or explained to me. Connecting with Eve filled me with conviction, vision, and purpose. She taught me to take ownership of my spirituality and that my access to my Heavenly Parents is mine alone to claim.

I didn’t know how sick I was until about a year postpartum. Darkness had steadily filled my periphery, manifesting as panic attacks, bursts of rage, and deepening wells of shame. I would see my friends parent their broods of children with seeming ease and wonder what I was doing wrong—maybe I really was this bad at mothering more than one. My narrow preconceptions about postpartum mental health kept my insights limited and my options few. My husband, a daily witness to this gradual and dark descent, didn’t know what signs to watch for or even what questions to ask. We both were lost in the dark, not even knowing the lights had gone out.

I didn’t know what to make of my pounding heart and consistently tight chest, my inability to breathe fully or slowly, the daily dread I felt upon waking. Outwardly I faked a brave and tired smile, assuring myself and others that things were fine, because what else was I supposed to say? Sometimes I believed myself.

The labor turned dire in what felt like an instant. I had an epidural and was hoping to steal a couple hours’ rest in the midnight hospital room before my daughter would stake her claim in the world. We breathed easier when we turned off the overhead fluorescents, calming ourselves in the simple glow from the sconce wall lighting. The nurse came in just as I was about to fall into a medicated doze.

“Could we move you to your side maybe?” she asked. She wedged an inflatable bean-shaped pillow between my legs, and I realized with resignation that I wouldn’t be sleeping any more that night. I glanced at the heart rate printing out on the machine next to the bed.

“What’s wrong?” I asked. “Do I need to be worried?”

“Oh, nothing we haven’t seen before!” the nurse replied, a little too upbeat to be convincing. A tense, unspoken current of doubt cut through the conversation. I glanced at my husband for reassurance just as his eyes darted to mine, needing the same.

My baby’s heartbeat was irregular, changing with each contraction. The nurse moved my numb legs around, trying to position my body and uterus such that my daughter’s heart rate would stabilize, hoping that steadying her pulse would be an easy fix.

Time in labor contracts and dilates, and I don’t remember the doctor coming in. In one memory, the room is dim and sleepy, and the next is buzzing with fluorescent light, beeping machines, and a cadre of nurses in constant motion. That cozy glow of pre-baby anticipation shattered as the hospital reminded me that this was no place for comfort. I was here to do a job, and my daughter’s life depended on it.

I couldn’t feel anything, not my legs, not even that singular urge to bear down and push. But I pushed when they told me to. Her heart rate continued to fluctuate. The nurses, once personable and encouraging, flipped to professional and clinical as if on a switch. I was a body in a bed, divorced from my mind and heart.

“You have one more chance to push this baby out,” they told me. One more chance before emergency measures would activate.

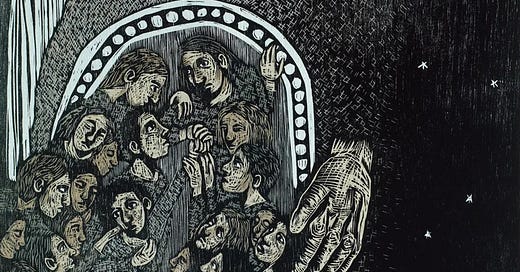

I pushed one last time and entered a liminal space, neither here nor there. The hospital room faded around me, and I felt, rather than saw, a tunnel full of light, a glowing nebula of potential and power. The light here was soft and kind and full, quiet and pulsing with purpose. Mothers lined the tunnel, the veil parting as they held fast to each other, channeling their combined power and all-consuming love directly into me. My grandmothers, their mothers, the Mother of all Living, my Mother—we were all together in that place that isn’t a space, connected in mind, body, and soul, infusing love and life into every breath and cry.

She came. My daughter came, and her heart beat the way it should. But my womb still bled. Blood with no source spilled onto the tiled floor, my vision blurred, yet I felt still connected to that tunnel built with love and sustained with strength. My daughter had arrived, but I had yet to follow. The matriarchs still held me, maintaining the celestial connections woven between us and my earthside infant, the stardust in the air preserving, protecting, and saving.

I don’t know what happened to stanch the bleeding, what anyone did to save my body. Whatever it was left my limbs shaking, the connection between my mind and body crooked and wounded. And that beautiful tunnel had closed, closing off part of my mind and heart with it.

We went home and entered the timeless newborn vortex of midnights and feedings and swollen belly and breasts, tears that can’t be named as happy or sad or even tired. Life went on and yet was entirely changed. And I didn’t know who I was or how to be anymore. I cared for both my daughter and my toddler son, trying to hold on to the breaking pieces of myself.

I can’t tell you much about that year, because those months gave no room for those moments to root into memory. They are seeds thrown on thorny, stony ground. I have photos and even video to prove that these moments happened. But were I to try and recall my own life with my baby, I could not, my memories a fallen rung on a ladder.

To say that I found Heavenly Mother wouldn’t be entirely correct. She found me, touching my raw and desperate soul just enough to remind me that She was there, that the tunnel of light that had once enveloped me hadn’t completely closed. She met me in the fourth watch, holding us both tight to her breast as I rocked my baby girl in the pre-dawn. She held me when my sick mind cut off my energy and feeling. She moved in the background, asking for nothing but to love me. I don’t remember the moment when I entered the eye of the storm and could clearly see the raging winds surrounding me. But I do recall knowing what to do. What to say and to ask, who to tell. When I finally gasped that desperate cry for help, my Mother was the first to grasp my flailing hand, keeping me from drifting even further into the depth of the tempest, promising me deliverance.

Slowly, surely I recovered. Maybe even healed a little.

I write this as my almost eight-year-old daughter laughs downstairs, leaping into an intrepid game of make-believe with her brothers, abandoning her intricate art project for later. Her joie de vivre fills our home like sunshine pouring through a southern window. I try to hold on to every moment of her kindness and curiosity and solar energy, marveling at the gift of our converging orbits. Our Mother’s love shimmers on all the gossamer strands connecting my daughter and me, making our mutual affection glimmer and shine so that, when I’m with her, heaven is always in the periphery.

But those first twelve months are still dark matter, unknowable and unreachable.

I don’t remember—

and yet.

At some point beyond my grasp of memory, a chain of strength and love reignited through my bones and tissues a cellular memory of that in-between space I once visited, the space filled with light and mothers. And just as I know that every day we turn back toward the sun, I knew that all the memories I thought I’d lost were not lost at all. My host of progenitors, all of us linked through our very cells—daughter to daughter to daughter, folding over and back again to Mother, crossing continents, planets, light-years through infinite, nameless suns—these women of wisdom and love now safeguard my daughter’s tender infancy, those moments my mind had to release in a last-ditch effort to survive.

The mothers caught them, stood under the falling stars and held fast to every drop and beam of light that I had lost.

She will restore those memories to me. Someday. She pulls them out, relives them, keeping them alive and breathing for me, loving them the way a mother counts every finger and toe on her newborn babe, promising a restoration more intimate and tender than I’d ever dared to dream. We speak of restoration, and yet do we really think we can understand the depth and breadth of the restoration our Mother intends? Perhaps the miracle of the Restoration isn’t constrained to an institution or scripture, but rather the knowledge of singular wholeness beyond healing, a personal deliverance curated to a single, broken soul. Restoration, not just of the world, but of me, as a daughter. Countless single, broken souls spangled across the heavens, all of us shooting out light hoping to be seen, all delivered by a Son beloved by His Mother.

She holds all my broken pieces, old scars and fresh wounds, eagerly waiting for my day of restoration, when I, with my daughter and her daughters, can walk through that tunnel of light into a star, into the arms of all the mothers who ever loved us, an expanse irradiating hope and wholeness enough to expand our ever-expanding universe, a restoration reassuring me I have always been known.

Charlotte Wilson is an editor and writer running a small business between school pickups. She lives with her family in the Pacific Northwest, loves watching shows late at night with her husband, and ignores the laundry piles in favor of a good book.

Sarah Winegar is based in Salt Lake City Utah, where she has worked since graduating from the University of Utah in 2017. She is a member of Saltgrass Printmakers where she continues to create in the print medium. She works primarily with relief printing, specializing in reduction woodcuts. Her work is about people; the human form finds itself in every piece regardless of the intent.

So so beautiful. Thank you.