I have always felt there was something haunting and exhilarating in Dale Thompson Fletcher’s work An Artist Called of God (Big Black). This painting had caught my attention in the past, but my interest was recently renewed thanks to the discussion of the work that appears in Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader, in Menachem Wecker’s excellent chapter on the Art and Belief movement. It struck me to learn that the work had “an almost mythic history,” that Fletcher felt he was moved upon in its creation, and that he had reported that the painting had “frightened him.”

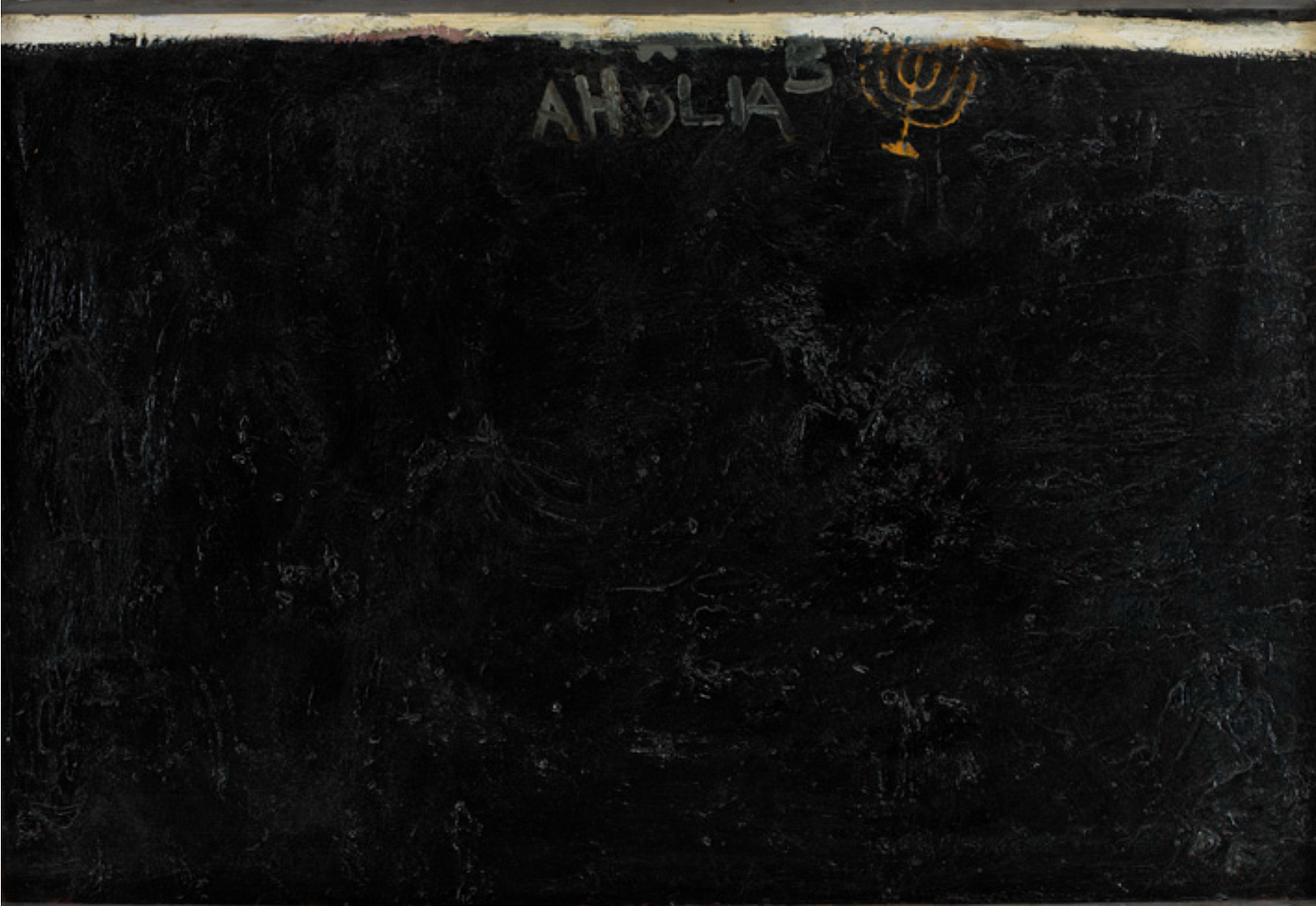

In An Artist Called of God a golden candelabrum seems to float atop a turbid, black abyss. Suggesting a menorah, the Hebraic instrument of light and of temple ritual, the candelabrum hangs on the edge of this dark space like a satellite on the horizon of a dimension into which we humans cannot see. Stationed at this border, jutting upward like an antenna, it becomes “a transmitter, a radio for speaking to God” And the person who receives its transmission (Fletcher, in this case) also receives a name, “AHOLIAB,” written across the top of the canvas in awkwardly ascending, gray letters. Significantly, the name refers to the artisan Ohaliav, who God called to build the Tabernacle in the book of Exodus. Something ancient is surfacing.

There is something about the tough, physical handling of the paint, text and imagery that tells us this revelation did not arrive as a gentle impression, but that it came to Fletcher like a burst of radio interference; something profound and dislocating; “a voice from the outer world”; a broadcast from across the expanse of deep space – like the deep,“immensity of space” we move through in the creation narrative in the temple.

In Latter-day Saint theology, the vastness of space—evoked in An Artist Called of God by the swirling mass of dark brushstrokes—does not symbolize God’s absence, but the infinite and awesome mystery of his creation. No portion of space is purposeless or inert. None of it is “pure space.” And the celestial structures and laws that govern its divine mechanics also shape how we know and experience God across incredible distances.

Richard Bushman has pointed out that one of the Restoration’s radical disruptions of 19th century Protestant theology was its positioning of “intelligence,” “truth” and “light” as key characteristics of God, alongside conventional attributes like love and mercy. For Latter-day Saints, God is not only a concerned father but the enlightened architect of the physical universe. For me, this means that the feelings of wonder I have toward God are not incompatible with the profound awe, and occasional anxiety, I feel in contemplating the unbounded cosmos.

In An Artist Called of God I experience all of these feelings at once: the numinous entangled with sublime delight, mystery and dread.

Chase Westfall is an artist, educator, and curator. He currently serves as Curator and Head of Gallery at VCUarts Qatar, Doha, Qatar.

Artwork by Dale Thompson Fletcher.