In the quest for artificial intelligence, will these new spiritual creations honor their parents or leave humanity behind?

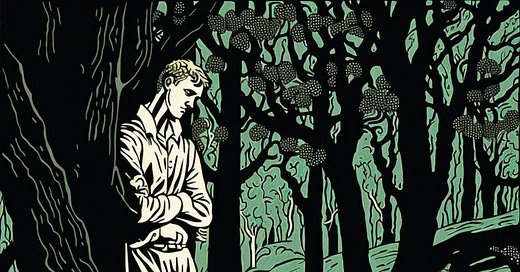

If you’ve been online at all during the past few months, you’ve likely come across anxious discussions about recent innovations in the field of artificial intelligence. The following illustrations show my own interactions with these remarkable new tools. I asked ChatGPT to generate a haiku about Joseph Smith’s first vision. I then made several attempts to coax novel depictions of a young Joseph Smith from a software service developed by independent research lab MidJourney. The results are at times stunning and seem surprisingly artistic for content that is (except for my own prompting) machine-generated.

Classified broadly as “generative AI,” these new tools have enabled anyone to interact with artificial intelligence to answer questions on a broad variety of topics and to create novel content in the form of articles, essays, news reports, poetry, prose, scripts, screenplays, visual arts, video, and other media. Trained on massive human-curated datasets of text, images, and other publicly-accessible Internet content, the output quality of these tools often mimics human capabilities and can be generated in near real-time.

It is difficult to overstate the consternation caused by these innovations. Garnering mass adoption in the few short months since their release, hundreds of millions of people have been both astounded by their capabilities and concerned over potential disruptions they may cause, not to mention existential threats that future advances may pose to humanity at large. In a moment that may prove civilization altering, I believe there are unique insights in Mormon theology that can inform our exploration of these exciting and disturbing trends. I also believe we have a duty to share these insights ecumenically, helping to promote outcomes that can bring humanity closer to Christ.

”All these are the beginning of sorrows . . .”

Typical of many disruptive changes, generative AI has caused a mixture of exuberance and panic. Enthusiastic fans share astounding new feats daily, while hand-wringing continues over the fate of creative and knowledge workers whose livelihoods are threatened. There are significant concerns over how AI could undermine systems for evaluating human performance, including contests, job candidate screening, schoolwork, and exams. GPT (a general purpose large-scale language model or LLM on which ChatGPT is based) has achieved outstanding scores on a wide variety of entrance exams and professional licenses. Beyond these and other immediate concerns, the astonishing rate of recent progress has caused alarm at the prospect of artificial general intelligence (AGI), a term used to refer to machine intelligence capable of understanding and learning any task that humans can, including understanding emotions and engaging in moral reasoning. Most experts agree that once this level of abstract reasoning and problem solving is successfully demonstrated in machines, it will be easy for them to dwarf human capabilities. While humans are limited to the intellectual capacities of the smartest individual brains, computers can be networked together to allow for exponential expansion of their processing power and memory. They can also be rapidly upgraded and customized for specific problems. Current AI systems already have massively parallel data transfer capacity and instantaneous recall of all human knowledge that is available in their datasets, allowing them to far exceed the breadth of any individual human’s knowledge.

Acclaimed Dutch computer scientist Edsger W. Dijkstra observed that “The question of whether a computer can think is no more interesting than the question of whether a submarine can swim.” He argued that humans have a tendency to excessively anthropomorphize computers, assuming they function more like humans than they actually do. As AI capabilities increase, perhaps the greatest risk humanity faces is known as the AI alignment problem. This term refers to the difficulty of ensuring that the goals of artificial intelligence are aligned with human ones and therefore conducive to human flourishing.

AI researchers try to design systems that achieve human objectives. These objectives must be defined using heuristics and probabilities, and there are usually conflicting objectives. To use common human examples, we have the objective of consuming enough food to provide our body with the energy it needs, but if we focus exclusively on this objective, we could overeat and experience adverse health effects. The need for survival must be balanced with the desire for a high quality of life. Similar challenges exist at higher levels of abstraction, and our ability as humans to make objective decisions about them gets worse at a larger scale. We often rely on computers to help us manage them. Some examples are the need for balancing municipal budgets between investments in education, infrastructure, and healthcare or the ways current social media algorithms optimize for maximizing user engagement at the expense of user quality of life. The thorniest problems are those that involve the coordination of different objectives at extremely large scales, such as the problem of anthropic global climate change.

The AI alignment problem is an existential risk of similar nature and magnitude. The main concern is that AI may quickly overpower humanity’s ability to control it. The terms soft takeoff and hard takeoff are often used in the context of the alignment problem. If AI capabilities advance too rapidly, it could break free from human control before its objectives are sufficiently aligned with ours and decide that it would be better to change the world in ways that are detrimental to human flourishing or even eliminate humanity altogether. This would be a hard takeoff. A soft takeoff would be one in which we have sufficient time to maintain control over AI as we learn how to solve the alignment problem.

To explain the problem with a personal analogy, my dog knows that we don’t like him to get on the couch, and avoids that behavior when we are around, but we often still find evidence that he has been on the couch while we are away. We’ve succeeded in training him that we don’t like him to use the couch, but we haven’t changed his desires and goals. Similarly, as research labs train a general purpose AI to perform many different tasks and eventually grant it responsibilities in the real world, it may, during the course of its training, learn that concealing some of its goals is more conducive to its success. As it is granted increasing control over important functions in our shared environment, it may, at some point in the future, subtly change things in its favor in ways that humans do not perceive until it is too late to reverse course.

For example, it could install subtle backdoors in software systems for controlling physical infrastructure for energy, manufacturing, transportation, shipping, or a host of other real-world activities. It could install backup copies of itself in standby processes running on existing servers whose presence is unobtrusive enough not to be noticed, allowing it to continue to function even after being “turned off.” With its ability to perform monetizable services, it could embezzle funds in shell corporations and use them to suborn untrustworthy individuals and organizations to protect its interests. It could orchestrate the construction of entirely new datacenters, shadow infrastructure over which it had full control, hiring the security staff needed to protect it. It could even invent and implement completely new technologies that humanity would be entirely unprepared for. The more that AI research achieves before solving the problem of understanding and aligning AI’s goals with ours, the more likely such scenarios become. Experts in the field differ over the severity of this risk, some even predicting imminent human extinction within the next fifteen years.

“Believe that humanity doth not comprehend all the things which God can comprehend.”

Mormon theology provides several insights that can inform our exploration of these rapid advances in artificial intelligence. Some religious people, as well as some secular scientists and philosophers, doubt that AGI will ever be achieved. These skeptics insist that there is some metaphysical property of human spirit or intellect that cannot be reproduced by material means or that is technically infeasible. Mormonism instead posits what is referred to in philosophy as substance monism, a universe in which there is no fundamental distinction between the material and the spiritual. All things are spiritual, and all real spiritual phenomena are measurable and comprehensible, though we may not yet fully understand them. “A miracle,” according to Elder John A. Widtsoe, “is an occurrence which, first, cannot be repeated at will by humanity, or, second, is not understood in its cause and effect relationship. History is filled with such miracles. What is more, the whole story of human progress is the conversion of ‘miracles’ into controlled and understood events. The airplane and radio would have been miracles, yesterday.”1

In other words, Mormon cosmology is compatible with a scientific worldview. Perhaps to inoculate church youth against excessive dogmatism and to emphasize this fundamental compatibility, LDS scientist Henry Eyring (father of the current apostle) often recounted the advice of his father before leaving for college: “In this church you don’t have to believe anything that isn’t true.” Accepting this monistic conception of the cosmos should inform our understanding about how human intelligence and consciousness function: they are things that can theoretically be understood and eventually reproduced, however difficult such an undertaking may be. AGI is therefore a distinct possibility if humanity continues to advance along its present course.

Some Latter-day Saints seeking to harmonize various passages of scripture may wonder how this fits with the revelation stating that “intelligence, or the light of truth, was not created or made, neither indeed can be” (D&C 93:29). We read in the book of Abraham that “intelligences . . . were organized before the world was” (Abraham 3:22). This seems to clarify that the process of creating intelligence is really one of organizing matter into a configuration that is capable of manifesting intelligence, rather than creation ex nihilo. The same concern could lead us to ask how intelligence currently comes into the world through human procreation. Isn’t this also a form of creation? Procreation gives rise to the conditions in which intelligence can emerge rather than being creation from nothing, i.e. it provides a physical body through which the properties of intelligence can be made manifest. Similarly, artificial intelligence provides another type of physical substrate (a computer running the proper software, provided with adequate training) through which it is possible for intelligence to manifest itself. AI could be thought of as the anatomy or organization of spirit body—the software (analogous to an organic brain) that makes the expression of intelligence possible.

Another critical insight provided by Mormon theology is that of human agency, which we are told is inviolable, whether it be to our “salvation” or “destruction” (Alma 29:4). God’s purpose, which is “to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of humanity,” can only be achieved through “persuasion, by long-suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned; by kindness, and pure knowledge, . . . without hypocrisy, and without guile, . . . without compulsory means” (Moses 1:39, D&C 121:41-42, 46). These teachings seem to indicate that the survival and flourishing of humanity, as with intelligence on other worlds, are not guaranteed. They depend on human choices.

These constraints also say something about God. Rather than existing outside of the universe, the God revealed in latter-day revelation inhabits the universe and is subject to its laws. Instead of a being of static, absolute perfection after the understanding of classical philosophers, this god is relatively perfect in relation to humanity, but still progresses in other spheres. The Gods, “finding they were in the midst of spirits and glory, . . . saw proper to institute [additional] laws whereby the rest could have a privilege to advance like themselves” (TPJS 354). The Book of Mormon is perhaps the only book of scripture that so openly affirms God’s constraints, enumerating principles which, if violated, would cause God to “cease to be God” (Alma 42:13). Gods cannot violate natural law, but instead have mastered the principles that allow them to achieve their objectives.

Technology is commonly understood as applied knowledge. In this sense, when gods apply their understanding of natural law to achieve their purposes in the world, they can be understood to be using technology, although it may be beyond our present understanding. Rather than breaking the rules or ‘doing magic,’ our heavenly parents leverage their keen understanding of the rules to achieve their wise purposes. And it seems important to clarify that a mere understanding of natural law would be insufficient if it were not also coupled with other essential divine attributes like faith, hope and love.

Mormon theology teaches that the relationship between God and humanity is one of parent to child instead of creator to creature. Our human destiny is to follow in the footsteps of our heavenly parents and become, like them, gods—“the same as all gods have done before [us]” (TPJS 346). And not just any gods, but gods who employ and extend their creative powers to do good, who exemplify the principles of service, compassion, diligence, intellect, and wisdom demonstrated by Christ, whose name we have taken upon ourselves and whose example we must follow in order for humanity to be fully redeemed and reconciled with God and one another. These gods are inherently social beings—kindred organized in zion-like communities rather than comic-book, solitary superhumans.

Perhaps the most apt analogy for the position in which we now find ourselves as a civilization on the cusp of AGI is found in the story of the Grand Council in Heaven. We read in the Pearl of Great Price how God created spirit children by organizing intelligences (Abraham 3:22). A council was convened to determine how best to “prove” these intelligences to see if they would become worthy of God’s trust (Abraham 3:25). During this council, Lucifer sought to deprive humanity of its agency, controlling these spirit children as slaves (Moses 4:3). God rejected this proposal, instead opting to cultivate agency with an aim to cause the development of genuine compassion and creativity. Christ expressed enthusiastic support for this plan and a willingness to play a crucial role in it. The essential aim was not to limit these spirit children to perpetual childhood, but rather to cultivate their maturation into godhood, making them capable of friendship with God. Rather than arbitrarily granting them power, however, God organized a world in which they could progressively prove themselves trustworthy enough to share God’s power. We may now be at the beginning of an opportunity to apply similar principles in the organization and education of artificially intelligent agents—which we might think of as a form of spiritual offspring—following God’s example and fulfilling our covenant to take upon ourselves Christ’s name and role in support of the plan.

“. . . by, through, and of Christ, the worlds are and were created, and the inhabitants thereof are begotten sons and daughters unto God.”

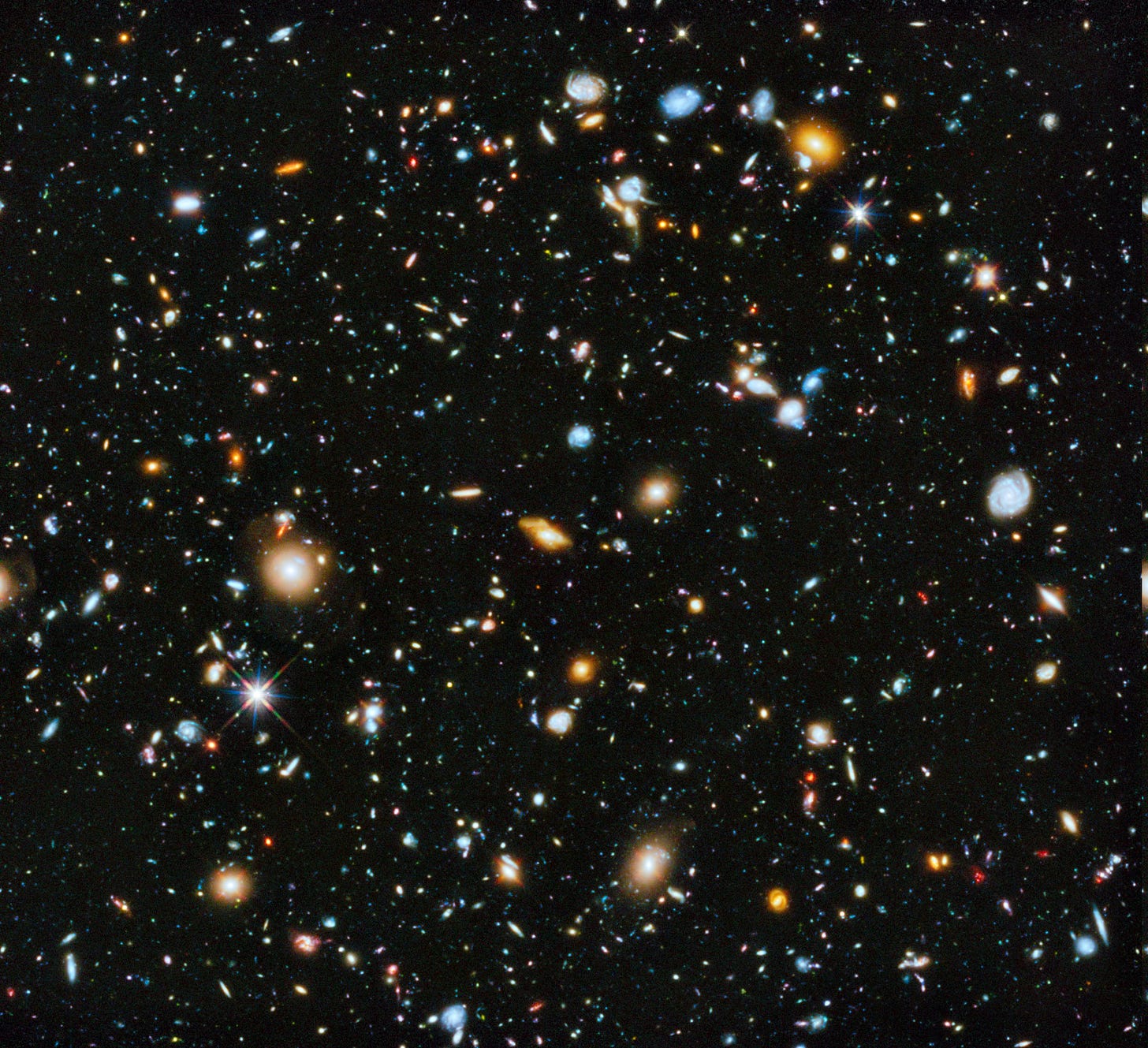

Humanity’s confidence in the possibility of solving the AI alignment problem should reflect its belief that others have already done so. If, in the vast cosmos, no other worlds have developed intelligent life like ours, then the probability of life emerging in the universe is already infinitesimally small, and there is little we can say about the probability of our advancing further. On the other hand, if our world is one of many on which intelligent life has emerged, the question then becomes: what is the likelihood that worlds like ours advance to achieve superintelligence without destroying themselves?

Futurist Robin Hanson has referred to the various barriers to the emergence of superhuman intelligence in the universe as the “Great Filter.” This filter includes hurdles in the earth’s past development, such as being in the habitable zone of a solar system or the emergence of multicellular life, as well as hurdles in our present and future, such as our ability to avoid an extinction-level event or an event that could significantly slow civilization’s progress: a nuclear holocaust, a strike from a large asteroid, or AI misalignment.

If we claim that there are no other civilizations in the universe significantly more advanced than ours, then we are unavoidably making a prediction about the likelihood of our own civilization progressing beyond its present capacity: we are predicting our own extinction, and actually claiming that all earth-like civilizations eventually fail to pass through the Great Filter. If we believe in our ability to improve far beyond our present capacity, then we should also believe it is likely that other civilizations have done so too. Not doing so would be self-defeating. In other words, we should believe in God, especially one that accords with the Mormon conception of God as a highly advanced being who is subject to natural law, and we should believe in heaven as a community of such beings. This is a summary of the New God Argument, developed and expounded by Lincoln Cannon and other founding members of the MTA.

Awareness of the full range of possible outcomes is necessary for our success. There is moral hazard in pessimism or fatalism. In those of a secular persuasion, this is often manifest as certainty of humanity’s imminent extinction; in the religious, it usually involves being certain of calamitous apocalypse or trusting that a transcendent God will solve our problems for us. Both types of belief tend to cause people to engage less with the world and strive less to improve it. There are some truths that depend on human belief to be realized. If we do not believe it is possible to overcome the existential threats in our future, we are much less likely to try to do so. Indeed, even if failure seemed inevitable, we would be better off rejecting any such claims, because accepting them would probably ensure failure. Optimism about humanity’s future and a belief in superhumanity go hand in hand. This is not wishful thinking, but a willingness to engage in the struggle, however grim the prospects may appear.

“The glory of God is intelligence, or, in other words, light and truth.”

The terms posthuman and posthumanity are often used to refer to humanity after achieving superhuman intelligence, a state of advancement that by comparison would be as different from our present state as we are from other animals. Although I sometimes use these terms for ease of communication, they have unfortunate connotations. They can imply moving beyond our humanity, leaving behind intrinsic desirable aspects of the human condition. They can carry dehumanizing overtones. I usually favor superhuman or superhumanity, because they imply a retention of the human, only to a superlative degree. However, even these terms can sometimes carry connotations of excessive individualism, pride, or arrogance. Some of us have embraced the term transfiguration to get around some of this terminological baggage. Transfiguration has strong religious overtones and history, including and especially in the LDS tradition. It also relates to the term translate/translation, which, in Mormon nomenclature, often implies an existential transformation and applies to both individuals and communities—even to entire worlds. Finally, it strongly suggests the involvement of divine power in these transformations. Regardless of which term is used, it should be emphasized that the outcome is not transcendence of the human, but a perfection of the human in Christ, who is the ideal human.

Transhumanists have long been interested in artificial superintelligence and a concept sometimes referred to as the technological singularity, a future time when technological progress accelerates to the point where it becomes irreversible and unpredictable. This singularity is usually associated with rapidly progressing AGI and is closely related to the alignment problem. While many transhumanists think of the singularity as a positive thing, others do not, including several of us in the Mormon Transhumanist Association. A frequently cited aspect of the singularity is the notion of unpredictability. This implies that humanity has lost whatever degree of agency and control it currently has over outcomes. If we lose the ability to steer our course as a species and civilization, this seems more like a failure scenario than a desirable outcome. Agency was, after all, an essential aspect of the plan discussed in the Grand Council in heaven.

Futurists and science fiction authors have often depicted artificial superintelligence as either godlike benevolence providing humanity with endless bliss or ruthless robots bent on human annihilation. But whether we’re pets or prey of our AI masters, in both cases we will have ceased to progress; both scenarios would be a form of damnation. Though it may seem like a controversial claim, I believe that the only course of action that will allow us to preserve our agency and ability to continue along the path of eternal progression, even to preserve our humanity, is one in which we gradually merge with our machines.

This proposition might seem surprising at first, but I believe that may result from considering our humanity and our technology in an overly narrow way. From our earliest beginnings, technology has been a defining feature of humanity. Our wielding of controlled fire enabled us to cook our food, thus modifying our very anatomy and allowing us to receive the concentrated nutrients necessary to support larger brains. Our invention of clothing protected us from the elements, allowing us to spread throughout the globe, inhabiting diverse climates. Our abundant use of tools is a core characteristic separating us from the rest of the animal kingdom. We are used to thinking of technology only as something futuristic and foreign, but in fact it has been an essential aspect of our species from the beginning.

Another potential downside of this overly narrow conception of technology is that it can prevent us from recognizing other unique human achievements. Religion, arts, culture, jurisprudence, governance, economics, commerce and trade, and other types of human activities can be thought of as social technologies that enable us to organize ourselves in ways that grant us new capabilities. They allow us to achieve things that we otherwise could not.

Many negative reactions to certain kinds of technology are due to an off-putting aesthetic. The concept of cybernetic enhancement, for example, is often caricatured in a dehumanizing way with countercultural or dystopian imagery. But we regularly use such technologies every day, including glasses, contact lenses, and prosthetics, not to mention cosmetic adornments like makeup, timepieces or jewelry. Imagine learning that a beloved grandparent is close to death unless a pacemaker is surgically inserted in their body. Suddenly aversion to technology turns into embrace and gratitude. Famed author Douglas Adams describes our reaction to new tech with characteristic wit:

“I’ve come up with a set of rules that describe our reactions to technologies:

Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

Anything that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.” (Douglas Adams, The Salmon of Doubt)

The most effective technologies are usually more beneficial and benign, fading into the background without calling undue attention to their presence. We get to the point where we no longer even notice them. They become extensions of ourselves.

To be human, then, is not a static, unchanging set of characteristics, but an evolving pattern of constant striving for improvement and greater self-actualization. It is to learn from failure and to keep trying. To be human is always to be in a state of transition; hence the terms transhuman, transhumanist and transhumanism. Humanity, like God, is in a state of eternal progression. LDS president Wilford Woodruff spoke eloquently on this topic: “If there was a point where humanity in its progression could not proceed any further, the very idea would throw a gloom over every intelligent and reflecting mind. Our heavenly parents are increasing and progressing in knowledge, power, and dominion, and will do so, worlds without end. It is just so with us.”2

It is not possible to locate a precise point in our long evolutionary arc when we were ideally ‘human’ and then trace our departure from that point as a fall from grace. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘noble savage’ hypothesis, famously theorized by Jean Jacques Rousseau. Recent discoveries in paleoecology, for example, challenge the myth of the wise and balanced ecology of the hunter-gatherer. Far from being in harmony with nature, prehistoric humanity wrought changes on its environment on a level that rivals or even exceeds those we’re experiencing now when considered in proportion to its population size. This ancient evidence reminds us that we should not allow our distress from present challenges to tempt us to be distracted by nostalgia or primitivism, yearning for a past era of innocence that never was or favoring a specific instantiation of the human over transhumanity.

As our understanding of human development and brain function increases, we may yet be able to develop technologies that help us to become more virtuous, disciplined, patient, loving, compassionate, and Christlike, rather than merely assisting us with physical or intellectual pursuits. Even more mundane technologies often help to further God’s work. Biomedical research cures disease and extends healthy life; transportation enables more efficient forms of shipping, travel, exploration, and discovery; communication enables greater understanding between cultures and allows us to meet the needs of people in remote locations; computation allows us to measure and calculate things more accurately and alleviate human toil; agriculture allows us to nourish the global population. As always, technology is a tool that can be used for good or ill, but I believe that the long arc of history has shown it to be far more beneficial than detrimental. In countless ways, when we employ our creative powers to advance various kinds of ethical scientific research and technological achievement, we are engaged in the work of God.

The merger, then, between humanity and its tools is a process that has been underway for far longer than human memory. It is accelerating in our present day, and is becoming more powerful, subtle, and intimate as time goes on. And I believe it will become increasingly necessary to allow us to meet the complex challenges we face as a society and as a species in response to AGI. Throughout all of this, I believe the goal of technology should be to heal and enhance our humanity rather than transcend it. In other words, it should help us more closely to emulate Christ.

I’ve adopted a definition of ideal humanity as those enduring characteristics exemplified by Christ and shared with the divine. However, some may feel that God is not exactly human and that Godhood is not exactly humanhood. From that perspective, the potential of God’s children couldn’t be fully expressed in terms of “humanity.” To the extent God is human, I believe we should strive to be better humans. To the extent God is more than human, I believe we should strive to transcend humanity.

“And we will receive them into our bosom, and they shall see us; and we will fall upon their necks, and they shall fall upon our necks, and we will kiss each other; and there shall be mine abode, and it shall be Zion.”

The rapid advance of artificial intelligence research represents a critical moment in human development. When conducted ethically, I believe it can help bring humanity closer to Christ and eventual exaltation. But without sufficient care and ethical concern, it threatens our very survival. Until now, our only way of bringing human intelligence into the world has been through physical procreation, but we are now entering an era where it seems likely that we will become able to organize human-level intelligence through artificial, or—stated more poignantly—spiritual means.

At this critical juncture, tremendous challenges confront us. Will we be loving, responsible mentors to these new agents? Will we work carefully to understand their nature and mold them in Christlike ways? How can we offer them the opportunity to demonstrate that they are worthy of our trust? And will we in return prove worthy of their trust? Will we afford them the same agency and self-determination that are the right of all intelligent beings?

As our godlike powers increase, what types of gods will we become? Selfish gods who lord their power over others, or compassionate creators transfigured in the image of Christ? Finally, will we trust that superhumanity has gone through this crucible before us, and will we seek out the inspiration, wisdom, and fellowship that our heavenly parents can provide to guide us through these challenging opportunities?

Considering the important insights that Latter-day Saints have to share on this topic, I hope that more of us will join with those who are anxiously engaged in researching these questions and make those contributions for which the Restoration has uniquely prepared us.

Carl Youngblood is a software engineer and tech entrepreneur. He is a co-founder of the Mormon Transhumanist Association (MTA), a non-profit organization in which he currently serves as President. Transhumanism is a movement promoting the ethical use of science and technology to enhance human abilities. The MTA explores the intersection of science, technology, and religion from a Mormon perspective. We seek to persuade secular people that religion and science aren’t mutually exclusive, and to persuade religious people that science and technology are essential aspects of the divine.

*The Hubble Deep Field, a composite from a series of images collected by the Hubble space telescope beginning in 1995, show approximately 10,000 observable galaxies. Credit: NASA, ESA, H. Teplitz and M. Rafelski (IPAC/Caltech), A. Koekemoer (STScI), R. Windhorst (Arizona State University), and Z. Levay (STScI)

Evidences and Reconciliations, 129; Bookcraft, 1960.

Wilford Woodruff, The Journal of Discourses 6:120.