A World Made for Us

An Interview with Ross Douthat

The New York Times columnist Ross Douthat has spent his career bridging worlds—explaining faith and conservatism to a largely secular audience while also translating secular ideas back to religious readers. In this conversation with Wayfare editor Zachary Davis, Douthat discusses ideas from his new book Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious, which makes a compelling case for why belief isn’t a blind leap into the unknown, but a rational and maybe even necessary response to the world as we actually experience it.

What kind of spiritual moment are we in?

I think we’ve passed through a period of crisis and decline for a lot of institutional forms of Christianity in the US and the larger West, and we’ve passed through a kind of high tide for atheism and outright skepticism and secularism that peaked with the new atheists, figures like Daniel Dennett and Richard Dawkins and the late Christopher Hitchens. There was a kind of maximal point of what you might call secular postreligious confidence, and I’d say it was pre-Trump, so about ten years ago.

And then the last decade has been quite hard on concepts of secular progress and optimism about what a world without religion looks like. There was a powerful narrative during my twenties that held that the big problem in the world was the persistence of religious fundamentalism, whether it was Islamist or Evangelical Christian or anything else, and that once you swept away creationism and biblical literalism and fundamentalism the world would enter a new era of science and progress and reason and enlightenment.

I think people have slowly but surely given up on that vision and have recognized that whatever the problems in the world, they are not essentially just about people being too religious. That politics after Christianity’s influence looks just as polarized, if not more so. The forces that have emerged as religion has declined—wokeness on the left, different forms of populism on the right—do not seem marked by great devotion to reason and tolerance.

And then there’s a lot of deep existential uncertainty and unhappiness pervading the secular world right now, to a greater degree than ten or fifteen years ago, some connected I think to technological changes to screens and social media and the retreat from reality into virtual life, some connected to Covid and its aftermath. But some of it is connected to people losing a kind of metaphysical horizon, and maybe wanting to have that back—feeling nostalgic for religion, feeling intrigued by religion but also feeling a stopping short.

I think a lot of people who have been reared without religion or who let their religion slip away over the last ten or fifteen years might like it back, but feel that as a serious, enlightened, educated, modern person they can’t really go all the way to embracing a traditional form of faith.

And so they’re in this zone of either personal uncertainty, hovering on the threshold of belief, experimenting with churchgoing, but feeling like it contravenes their reason, or they’re doing a kind of spiritual experimentation, a kind of dabbling that I think is very commonplace right now, people playing around with astrology or magic or psychedelics, forms of spirituality, or of quasi-Christian practices that don’t add up to any kind of formal practice or belief.

And so my new book is written to try and help people who are in that zone and encourage them to take religion seriously as something not in fact contrary to reason, modern science, but rather as a way of being that I think is basically obligatory for people if you take seriously what the universe presents to us, including through the findings of modern science.

There are two scientific revolutions that for many people remain powerful obstacles to belief. The Copernican revolution, which displaced us at the center of the known universe, and the Darwinian revolution, which displaced us atop some special hierarchy of being. But you argue there is a way to incorporate the truths of these stories as a believer.

Prior to the sixteenth century, there was a widely shared perspective on where Earth sat in the universe, the different hierarchies that planets represented, and so on. And this matched up with a biblical-cosmology vision of heaven and hell. And the Copernican perspective made the universe appear bigger and wilder and stranger than the cosmos as perceived in 1375, so it’s not surprising that that would have some unsettling effect on the worldviews of people in that time. And then Darwinism goes a bit further, raising some very pointed questions for Christians about both the historicity of the early books of Genesis and about the doctrine of the fall, how the story of Adam and Eve relates to the role that, in a Darwinian narrative, death and suffering seem to have already played in the emergence of complex life on earth. So if Christians say that sin and death entered the world with Adam and Eve, well, what does that mean if Adam and Eve are themselves the result of a long process of “red in tooth and claw” competition on earth?

With all of that said, neither Copernicus nor Darwin remove in any way the basic fundamental evidence for the universe as an ordered, fashioned, and complex system whose order and symmetry and complexity seem to strongly bespeak some kind of conscious intelligence as the point of origin. This is true of the Copernican Revolution, which reveals a bigger and wilder and stranger universe, but one that is governed in all its size and scale and splendor by deep and beautiful mathematical regularities that are totally amenable to scientific investigation and exploration by rational minds on a much greater scale than anything that was possible in the Middle Ages.

And Darwinism essentially asserts a kind of algorithmic origin for human life, a system running over a long period of time generating a diversity of complex forms of life, itself the structure of an ordered and regular and consistent cosmos.

And so the idea that Darwinism supposedly displaced was that a life form is a bit like a watch that you discover in a forest—a complex machine. And so you assume, well, if you found this complex machine somewhere, there must be a watchmaker.

And Darwinian atheists say, Well, no—we have explained where the watch comes from. It’s through this complex, million-year process of natural selection. You don’t need a watchmaker, you just need this process. But in fact, what you have now described is the equivalent of a watch factory. You still need a watchmaker, the ordered system in which that process gets started and plays itself out. And Darwinism doesn’t do away at all with the question of where that system came from, why it is so beautiful and orderly and mathematically precise and complex.

And further, that underlying order makes it appear not just remarkable, but frankly miraculous that it exists in the form that gives rise to you and me and plants and animals and everything else. What appears to be a kind of cosmic “fine tuning.” The extent to which there are many, many millions or billions of possible universes with all manner of potential laws and regularities and systems of order. And the odds of a universe like ours capable of generating complex life, to say nothing of conscious life, those odds are incredibly low. And by low, I don’t mean 1 in 10, I mean 1 in 10 to some absurdly high power of probabilities. In the words of the physicist Paul Davies, our universe looks like a cosmic jackpot. Basically, we have more reason than anyone did in the Middle Ages or the ancient world to think that the initial conditions of the universe were set with life-forms like us in mind.

So even if Darwinism to some degree has taken away one sort of obvious argument for divine intervention and special creation, the larger progress of science has given us more evidence of some kind of intentionality and special creation than we ever had before.

Earth is a very small place in a very big universe. But it’s the only place we know of where the thing that the universe seems to have been fine-tuned to do has actually happened.

You point out that given what we know of quantum mechanics—the way that observer and then the reality that emerges from that observation are so strangely interlinked—you could imagine that the universe as a whole functions that way with God’s mind as the universal observer.

One school of thought about the weirdness of quantum mechanics postulates the relationship between observer and reality, where the observer’s consciousness and knowledge is what collapses potentiality into reality itself.

That raises the question of what was going on with reality before there were conscious observers, and the religious answer is that in fact, mind precedes matter, and there’s been a conscious observer and creator all along. It seems, I think, to follow in a fairly reasonable way from that particular strange feature of reality as science analyzes it today.

How do you make sense of religious diversity? Why does the existence of many religious expressions not mean that they are false because they seem to be in many ways mutually exclusive?

And the atheists just go one god further, right? There are a couple different ways of looking at this. Obviously when you get to a certain level of theological granularity, there’s a really large array of religious choices.

If you go a step further, though, I think there are some pretty obvious patterns in religious history and development, a general movement that you see in human societies from early forms of religion that are very focused on an immediately enchanted cosmos, with any kind of god or creator gods sort of distant and inscrutable forces, to what I would consider forms of religion that are more focused on the higher God, the higher reality, and whatever he or she or it demands.

And that the more immediate expressions of spiritual encounter to that higher reality tend to envision not identical, but convergent, moral codes. Buddhism and Christianity are quite different in many ways, but the Noble Eightfold Path and Jesus’s ethics in the New Testament are not worlds apart. You don’t read them and conclude that these are completely different visions.

And there’s also convergence in perspectives on the nature of the cosmos. Hinduism and Buddhism both believe that you can die and go to heaven or die and go to hell. They also believe in reincarnation. They don’t necessarily believe in permanence in those experiences, but there is overlap in those perspectives between Eastern religion and Western religion.

And then obviously once you get into Islam, Christianity, Judaism, and so on, you get more convergence and more overlap. I actually think that the would-be religious person is facing not 1,472,000 different options, but a smaller group of evolved religious traditions that have important distinctions, like monotheism versus polytheism or reincarnation versus resurrection.

These are real choices, but I don’t think the diversity you are presented with is so wild and complex as to make some kind of orientation impossible. I think there are four, five, six big religious choices a reasonable person can make. So one can analyze where those religions differ, make some very provisional judgments and try and let Providence hopefully work on their decisions.

Also, the different religious pictures are not mutually exclusive in an impossible and fundamental way. A devout Muslim does not believe that Jesus Christ was the Son of God. But a devout Muslim believes in the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and believes that Jesus was one of his greatest prophets. So if you’re doing a Venn diagram of beliefs, there is some crucial overlap in terms of perspectives on reality.

To go a bit further, a devout Hindu doesn’t have to believe that the god of the Old Testament is a myth or a confabulation. A devout Hindu might believe that this is one expression of an ultimate divinity, just as the gods of the Indian subcontinent are expressions, and that the Jews may have overrated how important their God is, but it doesn’t mean those experiences are unreal. Similarly, a Christian looking at pre-Christian religion doesn’t have to believe that it’s all just made up. Christians can believe—and early Christians certainly did believe—that non-Christian forms of polytheism anticipate Christianity in certain ways, and that there are things implanted in those religions that look ahead to Christian belief.

I don’t think that Christianity excludes some weird religious possibilities that we don’t fully understand. You can say, I’m a Christian. I believe in this revelation. I believe in these specific teachings—and also say, you know, I honestly don’t know what’s going on with this category of spiritual encounter. And that’s OK because maybe there’s something that hasn’t been revealed to us.

I like this approach to religious diversity—you have this phrase, “it’s true-ish.” That you don’t have to accept every single aspect of another religion, but you can assume that it is pointing its followers towards a greater fullness. Latter-day Saints believe that God does indeed speak to all of his children, in language that they understand and in forms that they need, even while we embrace Jesus as the fullness of the revelation. I think it’s very generous to think of other religions not as false, but as localized expressions of God’s love for all of his creatures.

It’s a tricky point because, as someone who is a convinced Roman Catholic, I do want to insist on the importance of the differences between religions, and I agree with everything that you just said. I also think there’s a tendency to slide from that perspective towards a kind of soft assumption that all religions are basically the same and that God sort of created them all for different reasons, and the differences will just appear insignificant in the light of eternity. And I don’t think that can be right. I think it has to be the case that the arguments matter.

To take an example, either most souls are reincarnated or they aren’t. That’s a big question that has eternal consequences, and somebody’s getting it right and somebody isn’t. And, similarly, for Christians, either Jesus of Nazareth is who he says he is, allowing for some debate about what exactly that means, or he isn’t, and a lot turns on that question.

So in making this argument, I don’t want to suggest that the arguments between religions don’t matter. But, if you just look at the variety of religious experiences around the world, there are these fundamental similarities. There are visions of Jesus in the US that look a lot like visions of Krishna in India.

Some people argue that there are just incredible levels of spiritual deception out there, that demons are just out there tricking everybody. But I don’t buy that argument. The universe is not a trick. The evidence that we should follow is there for those with eyes to see, and I think you do have to take something like the LDS view you just expressed, that, even if Jesus is the son of God, God is still speaking to people in India sometimes in the terms that their religion gives them to understand the world.

And that if you are Chinese or Japanese and your religious practice is more focused on ancestors, you are going to see an ancestor when there’s a divine message for you, whereas a Catholic might see a saint or an angel. That is part of whatever the divine economy is and not just some sort of deception.

Why are you betting on Jesus?

Sometimes you have to just cast down your religious bucket where you are—if you read the Quran and have a powerful conviction that God is speaking here in a way that God isn’t speaking to you when you read the New Testament, then that’s a good sign that you should start there.

And my view, conditioned by my own religious upbringing, no doubt, is that the New Testament, the Gospels especially, stand out among all religious narratives for a combination of unusual historical credibility and unusual personal narrative plausibility. They do really feel like memoirs written by eyewitnesses, and I think there’s a very good historical argument that they are joined to the extremity of the miraculous claim. What’s striking about Jesus is that he does seem quite different from the merely prophetic figures who lie at the point of origin of a lot of different religious traditions.

And then just the absolute strangeness of the crucifixion and passion and resurrection among the religious narratives of the world. Out of all the religious stories available in the world, this seems like the most likely place where there’s a full divine break-in, if you will, a kind of controlling revelation, a controlling message, and a story, text, and person through which you then would read the rest of religious data.

What’s your prophecy for the next few years of Christian life in America?

I think we should expect weirdness. And I think weirdness definitely means there are more possibilities for serious religious and Christian revival than would have been the case ten or fifteen years ago. But you have to see them as possibilities, and the weirdness could go in a lot of different directions.

Ross Douthat is a columnist at the New York Times. His most recent book is Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious.

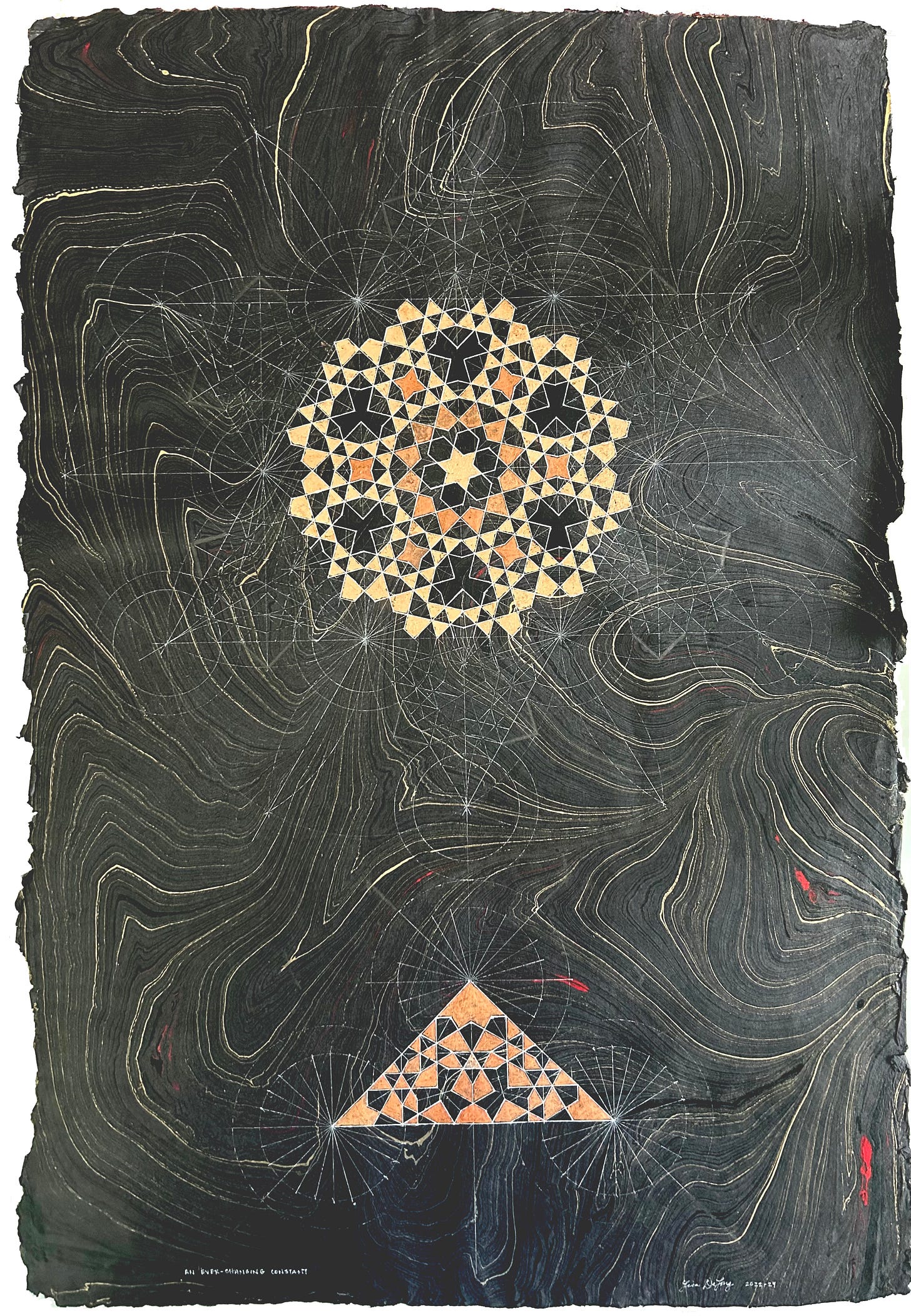

Art by Lisa DeLong.