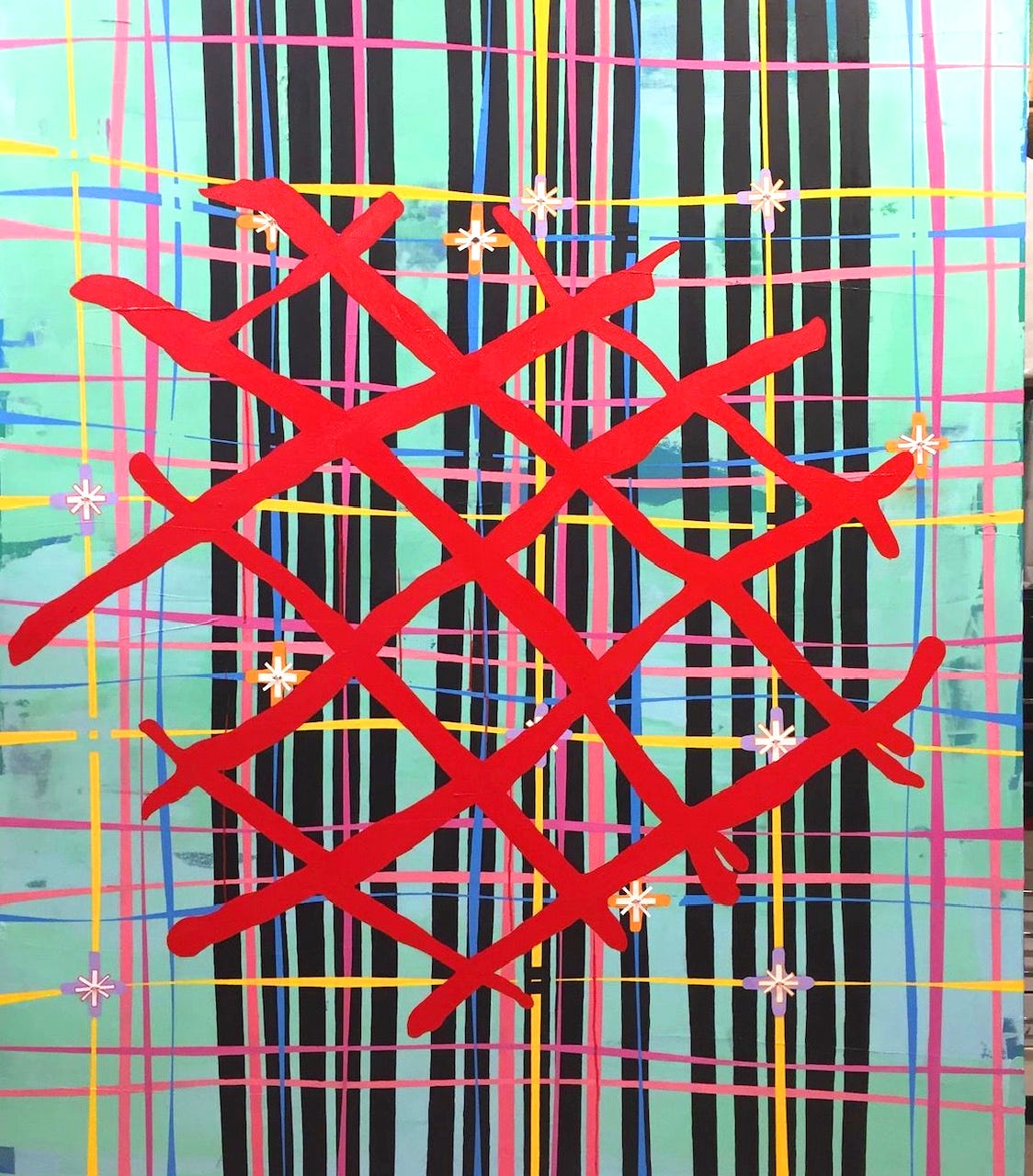

A Tapestry of Love

Forgiveness and the Task of Reweaving

There’s a joke among Asian Americans that to disappoint your parents, you simply need to exist. In Confucian ideology, children are the literal extension of their parents’ flesh—meaning that your every mistake reflects directly on them.

And there are many ways to make a mistake.

I was that rare, shining child my parents bragged about at dinner parties, the one they told my siblings to emulate—and the one who breathed a mental sigh of relief each time my parents said, “We’re lucky you’ve always been so obedient and easy.” As the oldest daughter of Taiwanese immigrants, I’d learned early on not to wrinkle the perfect tapestry of my parents’ pride. I worked hard in school, spent time with the “right” friends, attended church, and followed all the rules without complaint.

But I had a temper. And sometimes that temper revealed the frayed threads of my filial piety—especially with my mother.

As a teenager, I occasionally fractured my golden image and fell into tiffs with my mother over small things. She would nag me about something, I would shoot back snarky comments, and we’d simmer for a day or two before returning to normal, as if the argument had never happened at all.

I knew my mother was a difficult woman to love; she was critical of her children’s academics, weight, dress, and recreational activities. She would often remind my siblings and me that she had raised and fed us, and the least we could do in return was offer her our exact obedience. Our bodies and existence belonged to her, simply because we had come from her womb.

This idea was a thread I sometimes picked at but never yanked—because I wasn’t merely a daughter of Chinese immigrants. I was also a daughter of Christian converts, and to be Christlike meant to avoid contention. My father once told me, “I was attracted to the Church because its teachings are similar to Confucian ideology. The only concept missing from Confucianism is Jesus Christ.”

My parents love God, so much so that they uprooted our entire family and moved us from California to Utah, where most of the population shared our faith. They love the church they nurtured us in, and I learned to love it too. And in some ways, that love allowed me to look past my parents’ imperfections and respect them, despite their high expectations. It also allowed me to shut down arguments with my mother to prevent irreparable harm.

For a long time, I thought that would be enough.

When I was twenty-seven, my mother broke my heart. I had stopped squabbling with her in my early twenties, having established a peaceful relationship built on held tongues (me) and happy obliviousness (her).

But one December afternoon, we stumbled back into past patterns. I was wrapping Christmas presents on the living room floor while she ranted about one of my cousins, who had different standards of dress.

“Her clothes are too immodest,” my mother said. “Is she looking for trouble?”

“Of course not,” I said, attempting to defend my cousin. “She just likes to dress that way. It’s none of our business.”

“Girls shouldn’t dress like that,” my mother insisted. “She’s basically asking for men to assault her.”

I tensed at her accusation, staring hard at the creases I was pressing into the wrapping paper. My mother was a fierce woman, worthy of her tiger zodiac, but she often lent that fierceness to painfully outdated beliefs. Usually, I ignored her comments to keep the peace. But she had hit a particular nerve that riled my own ferocity.

“A woman’s dress is not an invitation for men to do anything,” I said tightly. “It is a man’s responsibility to respect women, whatever they’re wearing.”

“Maybe,” my mother replied, “but women have a responsibility too.”

I looked up then, my voice hard. “Are you saying it’s a girl’s fault if she is raped?”

“Yes, if she’s dumb enough.”

“Then I must be dumb.”

The words came out before I could stop them, before I could consider the consequences of such a simple response. But I had spent twenty-seven years maintaining my golden image—and I had spent twenty-one of those years swallowing a secret I knew would unravel everything.

“What do you mean?” my mother said. The room suddenly felt so quiet.

I paused long enough to remember that at six years old, I left the house with a man my mother trusted, who took my siblings and me to Chuck E. Cheese and brought us to the park when we were bored. I remembered that my brother and sister were sick that day, so they couldn’t go to the public library to play on the computers as planned. But I went, just me and the man. I remembered him driving me up into the California hills, parking in a secluded grove off the main road, and touching me in ways I did not understand. I remembered him buying my silence with a box of chicken nuggets from McDonald’s. I remembered returning home, my tears having already dried, and seeing my mother. We were going to a church activity at the beach that afternoon, and I remember her telling me, “Don’t let any of the men hold or touch you in a strange way,” thirty minutes too late.

For twenty-one years, I held my tongue in the hopes that my parents would remain happy and oblivious forever—or at least until we were all in heaven, too exalted to fret over earthly matters.

But that day, I felt angry enough to confess.

I looked back down at my Christmas wrapping and said, “It happened to me.”

My mother immediately began asking questions.

“When?”

“A long time ago, back when we lived in California.”

“Who was it?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

Even in my anger, I wished to protect my mother from potential guilt.

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

And then she asked the question I had been fearing for twenty-one years: “Why did you let that happen?”

I always knew my mother's thinking was narrow and unbending, limited by sexist assumptions and prone to victim blaming. But I convinced myself that as long as I told her nothing, and as long as she never asked that question aloud, I could pretend that she would respond differently—with love and sympathy and protectiveness.

But she asked that question. And in it, I heard her accusation: It’s your fault.

In church, I learned that a mother’s love for her child is the closest thing to God’s love for us. I thought that even my mother, whose culture practiced conditional love, would love me unconditionally where it mattered. But in that moment, I felt betrayed by the person who was supposed to love me most.

I did not speak to my mother for two weeks. It hurt to be in the same room as her, to look at her, let alone talk to her. I continued to punish her with my absence until one day, my brother gently but firmly reminded me, “Forgiveness isn’t for the offender. It’s for you.”

I thought of the Savior and how he’d asked the Father to forgive his murderers as he hung from the cross. Those words, “Father, forgive them,” did not change his enemies’ hearts. The men and women who’d condemned him did not even hear his agonized whisper. But Christ’s plea for forgiveness could clear his heart as he prepared to be perfected. It might even have brought him peace in his final moments of mortality.

I wanted that peace. And I was so tired of being in pain. So, I buried my anger and moved on. I spoke when spoken to and even found the ability to smile at my mother again. As time passed, I patched over the tapestry that was our relationship, concealing the knots and tears underneath with colorful new silk.

Still, my mother had affirmed my long-held suspicion that she was an incorrigible woman who cared more about her traditions and opinions than her daughter’s needs. I accepted it, and stopped expecting anything else.

Two years later, I had a mental breakdown, stemming from a general dissatisfaction with my life. I was pouring myself into other people’s cups and forgetting to fill mine, because that was how I’d been raised as a good Chinese, Christian daughter: dedicate your life to others while forgoing your own needs.

I poured and poured and poured until I turned one day and found depression holding my empty cup. And suddenly, everything else in my life felt empty too—my relationships, my service in church, my job, my hobbies, my passions. Fortunately, through talking to my church leader, therapist, and closest friends, I gradually pulled myself out of the emptiness and started to refill my cup.

A few weeks after, I sat at my parents’ dining table with my mother, confessing my recent struggle with depression.

“I’m working on it,” I said.

“But why are you depressed?” she asked. “Young people these days are always crying depression.”

I grimaced at the dismissal in her tone. But I responded honestly. “I’m not saying I’m suicidal. I’m just saying that sometimes I feel really, really burned out and exhausted and gray.”

“But why?”

In the past, I would’ve shrugged and given a vague answer, too tired to explain myself to a woman who seemed to want to contradict my every feeling. But my therapist had been teaching me about communicating boundaries and needs, and I felt brave enough to try.

“You really want to know why?” I knit my fingers together as I looked at my mother. “It’s because of you. Because you taught me to be this way. You and Baba always tell me to be a good example, and you always brag about me with your friends.”

“We brag because we’re proud of you.”

“I know, and I understand that,” I said, meaning it. “But it puts pressure on me, and it reinforces this idea that I have to be perfect, that I have to be responsible for other people all the time. I’ve been taught that if I have a problem, I have to swallow it and focus on getting other things done. And it makes me feel exhausted.”

My mother paused for a moment, then said, “You sound like your aunt.”

She was referring to her sister, also the firstborn in her family. I didn’t disagree with my mother’s assessment. My aunt and I both had a temper, a similarity I’d always noted in passing.

“Maybe it’s because we’re both the oldest,” I said.

“Maybe,” my mother agreed.

She looked at me, expression unusually calm and gentle. In my mind, my mother has always been the sharp-edged matriarch, her tongue existing only to spew gossip, dogma, or criticism. But at that moment, she looked thirty years younger, her dark eyes clear and compassionate.

“I understand,” she said. “I won’t do that anymore, put pressure on you. Just focus on yourself, and stop giving everything to other people.”

A disbelieving laugh tripped over my lips. “Really?”

“Yes,” she said. “I’m sorry I put that kind of responsibility on you before.”

I’m sorry.

My mother never said sorry—at least not without the words being dragged through her teeth. But there they were, so unexpected and casual and soft.

I recognized empathy in my mother’s response. For the first time, I felt that she was hearing me, listening to me, and humbling herself toward change. My mother had always been like a mountain, rigid and immovable. But that day, I noticed the trees on the mountain slopes shifting in the breeze.

“OK,” I said. “Thank you.”

In church, it is often said that repentance is change. But forgiveness is change as well. As I studied my mother that afternoon, I did not think she was suddenly a different person. Our relationship did not suddenly resurrect into something perfect. But I felt thin, gold threads of forgiveness weave through our tapestry, undulating over and under past hurts, offenses, and confusion. For once, I wasn’t ignoring the knots but allowing love—mine, my mother’s, and the Savior’s—to untangle and mend. I didn’t know what the tapestry’s image would look like in the end, but I had hope that it would reflect true peace and healing.

A few minutes later, I stood at the sink, rinsing out dishes, while my mother complained about my sister—still very much the mother I knew.

“She never listens to me,” she said. “You should talk to her about—”

“Hold on,” I interrupted. “What are you asking me right now?”

My mother paused, stared at me, then laughed.

“You’re right,” she said. “Never mind. Never mind.”

Tesia Tsai is a writer and teacher living in Provo, Utah. She received an MFA in creative writing at Brigham Young University.

Art by Daniel Callis.